Last time we looked at Mori Motonari, the lord who took his clan from struggling to hold onto their domains to controlling one of the largest territories of any clan during the Sengoku Period. Motonari’s son, Takamoto, died early, and so it would fall to his grandson, Terumoto, to lead the clan after Motonari himself passed in 1571.

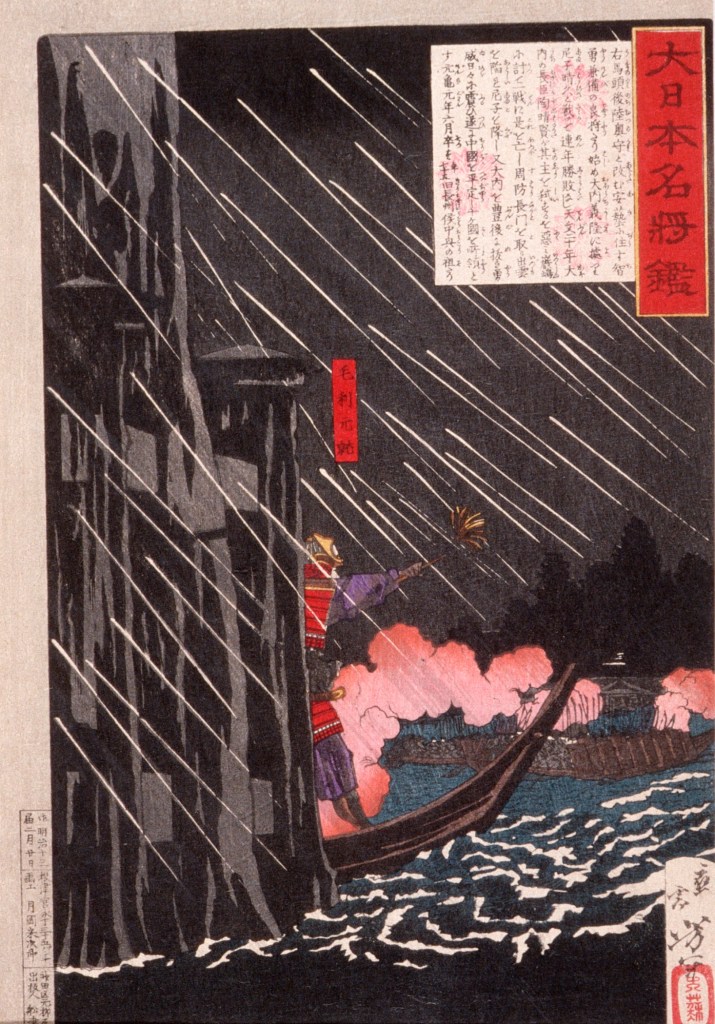

Terumoto was born in 1553, at a time when his clan, the Mori, were already on the rise. Under the leadership of Motonari, the clan had recently purged the Inoue, who had presented a serious internal threat, obliging Motonari to get rid of them. Shortly before Terumoto was born, the Ouchi, nominal overlords of the Mori, were seriously weakened by an internal coup, allowing Motonari to expand his clan’s power base still further, and not long after that, the Mori would win the decisive Battle of Itsukushima, establishing themselves as the (relatively) unchallenged power in the region.

Throughout his early life, Terumoto hardly saw his father or grandfather, as both men were frequently on campaign, and the young boy, as the future leader of the Mori, was kept safe, far from the fighting. Takamoto was, by this point, technically the leader of the Mori (though Motonari would remain in control), and when he died suddenly in 1563, Terumoto, just 11 years old, became the nominal head of the clan. Due to his youth, however, Motonari agreed to serve as ‘co-leader’, whilst (again) retaining all the actual power.

In 1565, as a sign of how far the Mori had risen, Terumoto’s coming-of-age ceremony was attended by an official representative of the Shogunate, lending formal (if only symbolic) prestige to the young man. After this, Terumoto, who was now legally an adult, became the official head of the clan, and from then on, most legal documents carried his signature, though he would continue to defer to his grandfather in practice.

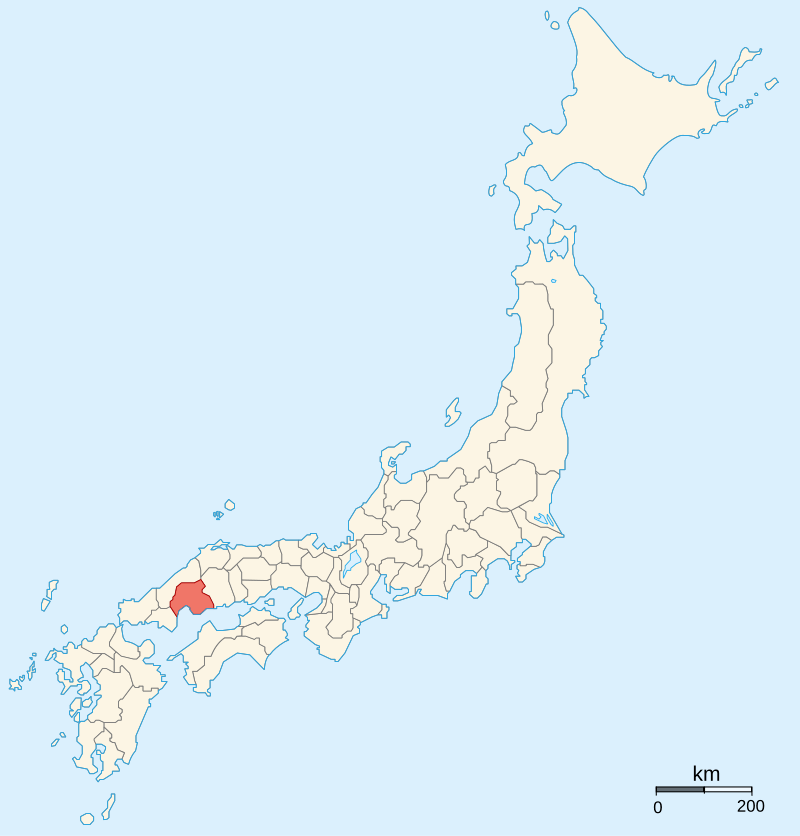

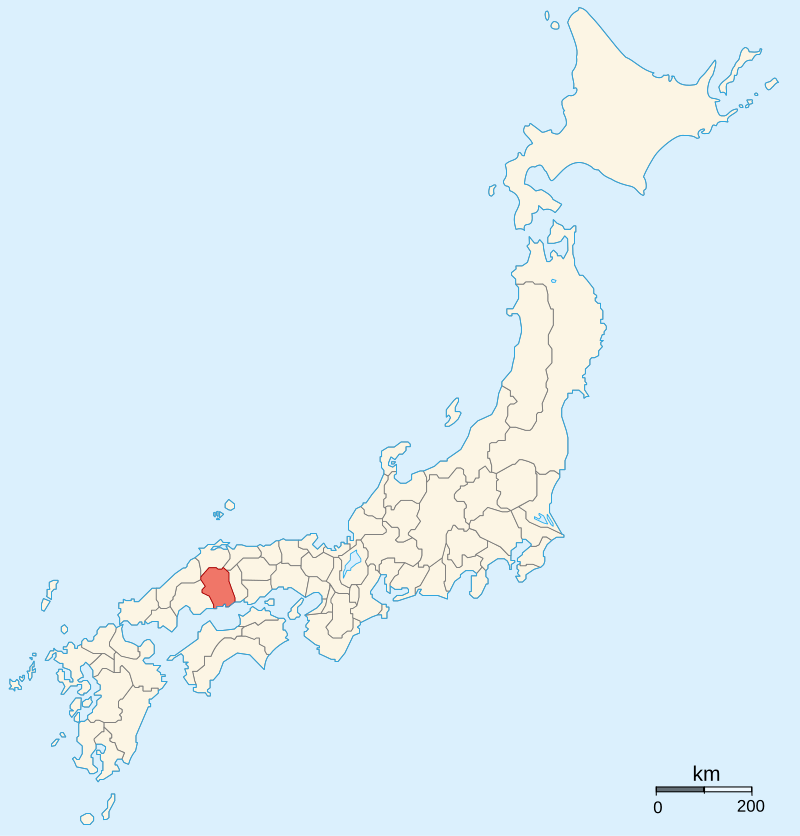

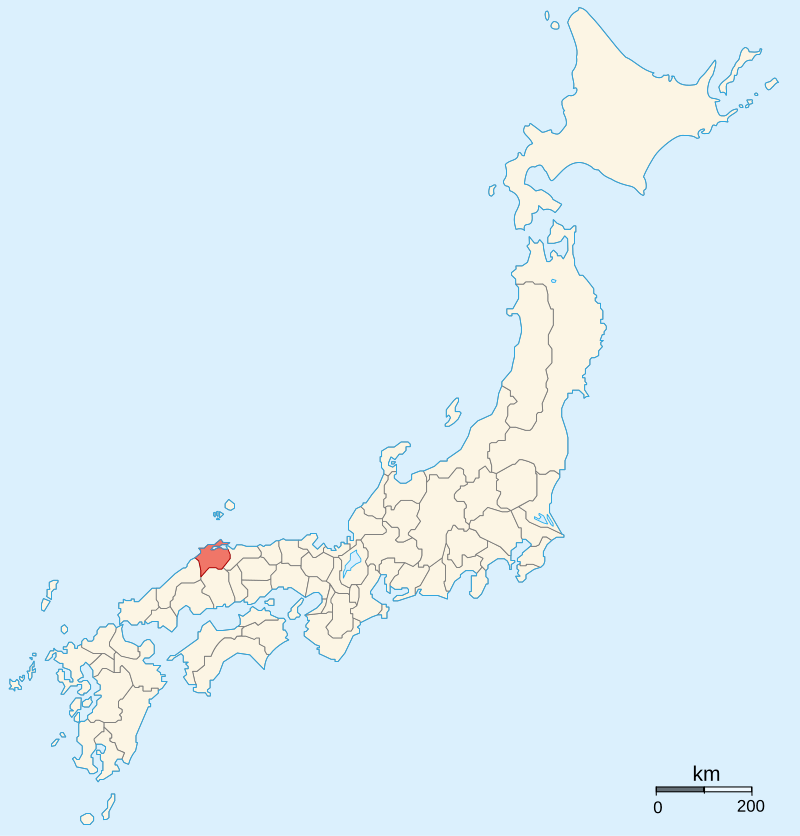

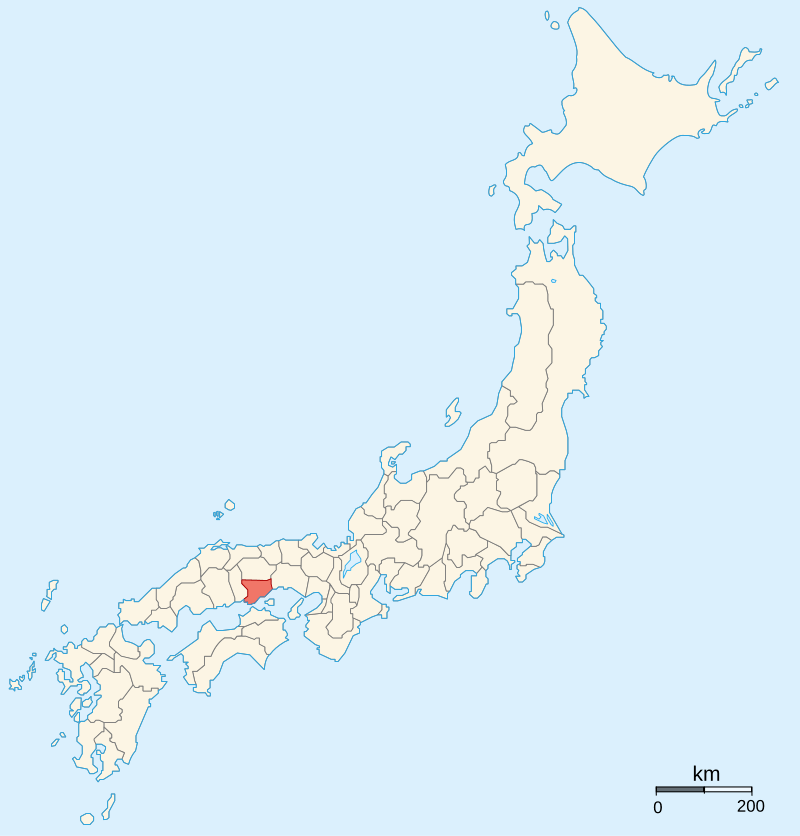

Later that year, Terumoto would join his grandfather in Izumo Province, taking part in the campaign against the Amago, who had once been strong enough to demand fealty from the Mori, but were now on their last legs. This final campaign against the Amago would be concluded successfully in late 1566, with the surrender of their last stronghold at Gassan-Toda Castle, signalling the end of the war and the Amago Clan.

安来市政策秘書課 – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=74692475による

Despite this victory, an uprising of former Amago retainers would occur in June 1569, followed by a similar uprising amongst former Ouchi warriors in October. These twin uprisings were either instigated or supported after the fact by the Otomo, whom the Mori had been fighting for control of Northern Kyushu with.

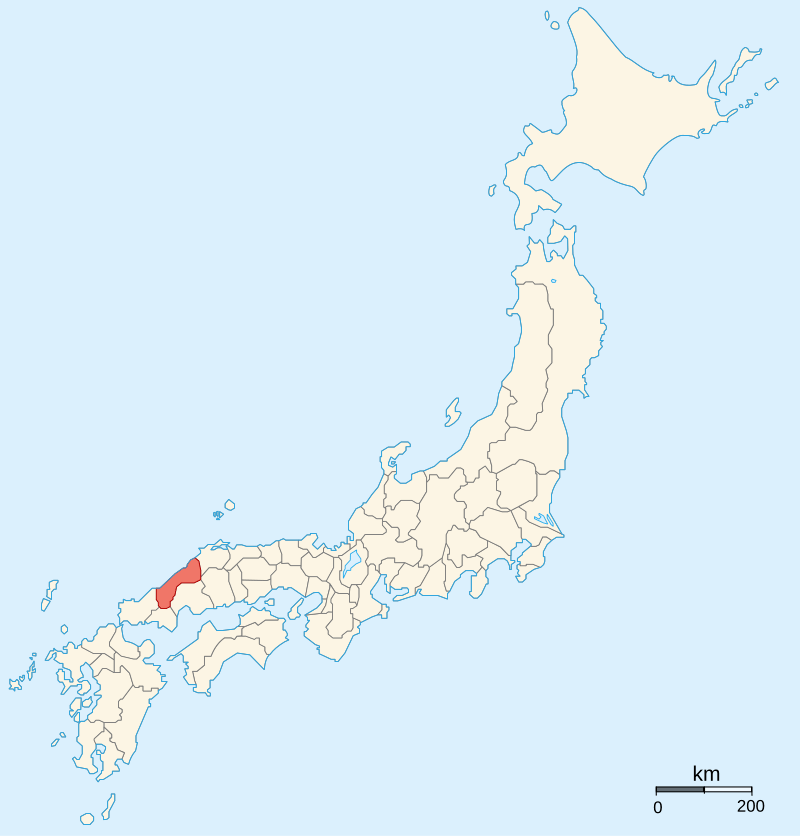

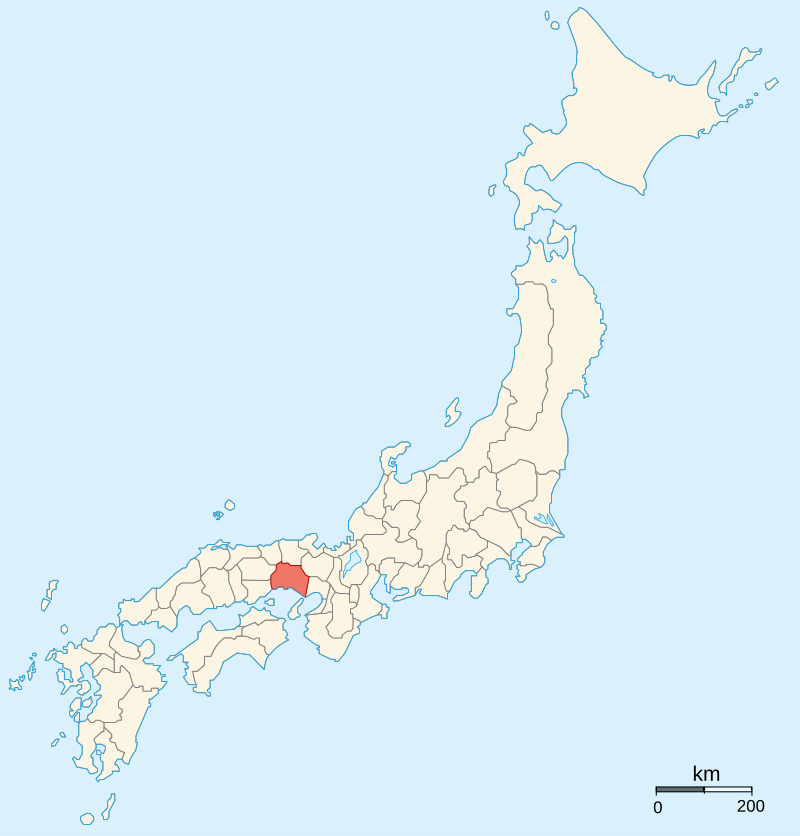

Mori control of Izumo, Suo, and Nagato provinces was suddenly under serious threat. Withdrawing forces from Kyushu allowed them to quickly deal with the Amago rebellion, but the Ouchi proved a much sterner test, and required the Mori to dedicate even more resources to putting them down. Though victorious in early 1570, the consequences were that the Mori lost all their influence in Kyushu and had to continue a long, bloody campaign, trying to stamp out the embers of the Amago.

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1691776

Around this time, wider events began to have an impact on the Mori as well, bringing them onto the main stage of events in and around Kyoto. Earlier, in 1565, Shogun Ashikaga Yoshiteru was assassinated in what became called the Eiroku Incident, and his replacement, Ashikaga Yoshiaki, went looking for support from the clans further away from the capital.

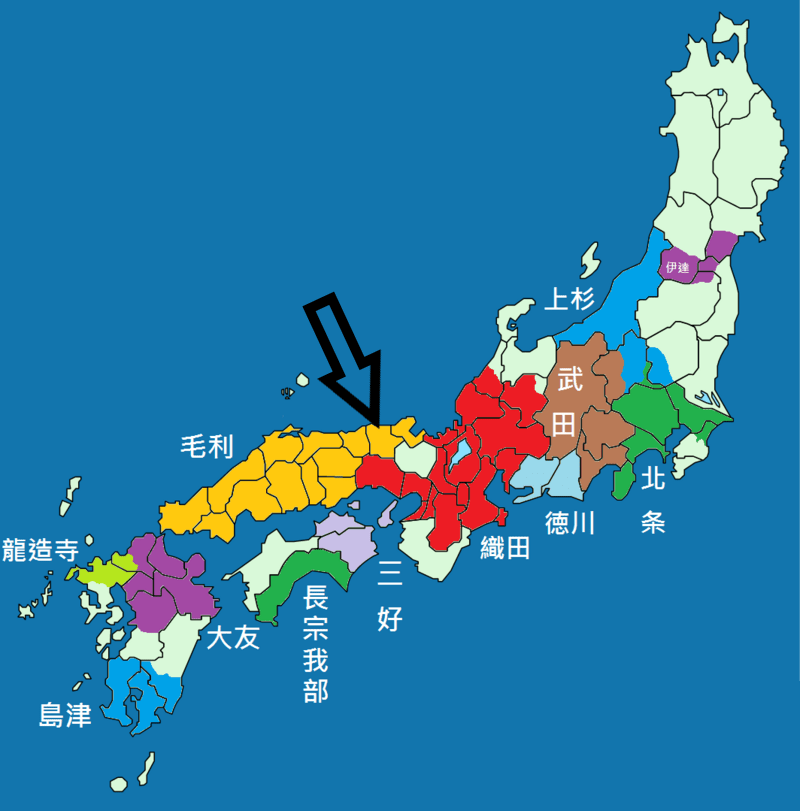

In 1568, the new Shogun dispatched a request for aid to several powerful leaders, including Uesugi Kenshin, Oda Nobunaga, and Mori Motonari. The Uesugi and Mori refused, but Nobunaga, based closer to the capital and possessing uncommon ability and ambition, responded positively and dispatched forces to Kyoto.

Not long after that, the Oda and Mori began to cooperate against their common enemy, the Miyoshi (who also happened to be the clan behind the assassination of the previous Shogun, which was handy). Over the next few years, an alliance would be established, and Nobunaga would actually dispatch forces to help the Mori put down the Amago and Ouchi, but beyond that, there would be little direct cooperation.

When Mori Motonari died in 1572, leaving Terumoto to lead the clan alone, relations with Nobunaga were already in decline. Previously, the Mori had sought to use the authority of the Shogun (by now under Nobunaga’s control) to advance their own goals, and for a time, Nobunaga was happy to acquiesce, but after 1572, it became clear that Nobunaga had plans of his own that didn’t necessarily involve the Mori.

Though the Shogun had largely been under Nobunaga’s control since 1565, at first, it had been a subtle arrangement. Nobunaga was in charge, but Yoshiaki was permitted to still act like the Shogun, even if his commands and proclamations (such as they were) were increasingly screened and eventually written by Nobunaga.

Yoshiaki didn’t passively accept this, however. His problem was that he had little military strength of his own (a problem for the Ashikaga Shoguns since the very start), and with Nobunaga’s pre-eminent military position, the Shogun needed help. He thought he might find it in the Mori, one of the few clans that had the strength to challenge Nobunaga directly.

In 1573, at the recommendation of the Shogun, Terumoto was granted the title of Uma no Kami, which translates as “Master of Horse”. Though Imperial titles had long since become little more than baubles, they still carried prestige, and Yoshiaki almost certainly did it to butter the Mori up and bring them over to his side, against Nobunaga.

Yoshiaki was desperate by this point. Earlier that year, Takeda Shingen, who had agreed to march on Kyoto at least nominally in support of the Shogun, had died suddenly, bringing an end to the prospect of Takeda support. In early Spring, Yoshiaki raised an army anyway, hoping to take advantage of Nobunaga being distracted elsewhere, but instead suffered a series of defeats, which culminated in the Battle of Makishima Castle in July, which saw Yoshiaki exiled from Kyoto.

Muscla3pin – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=77200674による

Shortly after this, Nobunaga, aware of his vulnerable position, wrote to Terumoto, assuring him that it was the actions of the Shogun that led to Oda troops formally occupying the capital, and that he would do everything he could to maintain peace in the realm. Given that there hadn’t been peace in the realm for more than a century at this point, it leads us to conclude Nobunaga was just being polite.

Though Terumoto probably eyed Nobunaga’s expansionism warily, the alliance was, for now, convenient for both sides, as it largely secured the border between the two powerful clans and allowed them to carve up the territory of the smaller clans caught in the middle. Terumoto did continue to try to mediate a peace between Yoshiaki and Nobunaga, though neither side seems to have negotiated with much faith.

Scholars speculate that both Terumoto and Nobunaga wanted to avoid a situation in which the Shogun would flee to Mori territory, Terumoto because had no interest in helping Yoshiaki, but couldn’t rely on some of his more tenuous vassals not making trouble, and Nobunaga for pretty much the same reason, the Mori were one of the few clans strong enough to oppose him, and if they backed the Shogun, Nobunaga might be in trouble.

Though Nobunaga was allied with the Mori, he took other actions that would be considered unfriendly. On the Eastern borders of Mori territory (the West, as far as Nobunaga was concerned) lay the Urakami Clan, who dominated the three provinces of Bizen, Harima, and Mimasaka. The Mori and Urakami had engaged in a long war before the Urakami had agreed to submit to the Mori in exchange for recognition of this territory, terms to which the Mori agreed, effectively turning the Urakami into vassals.

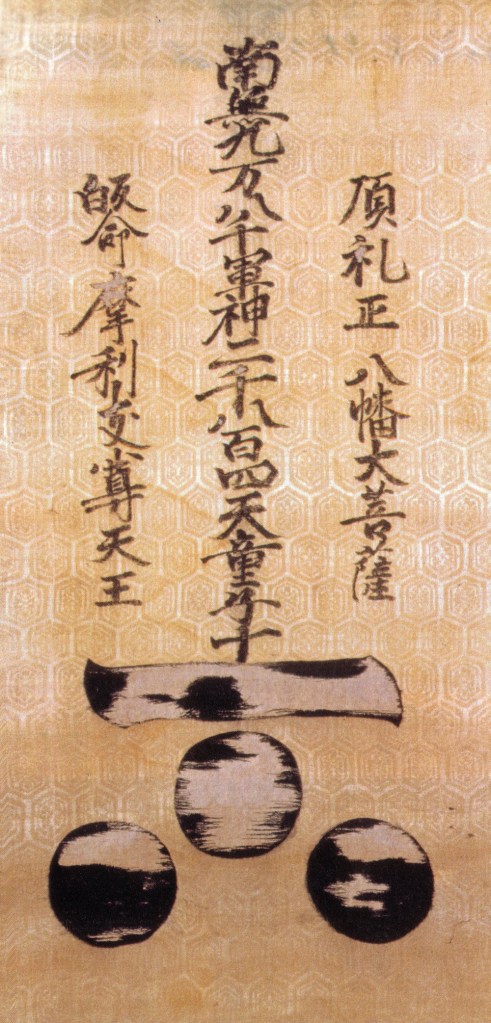

However, Nobunaga issued a “Red Seal Letter” (an official, legally binding document named for its eponymous red seal), recognising the Urakami as lords of the three provinces. This was, in effect, simply making official something that was already a fact; however, when the Urakami accepted the letter, they effectively ceased to be Terumoto’s vassals, that is, if the Mori accepted the new situation.

The Mori, not surprisingly, did not. In 1575, they attacked the Urakami, defeating them in a series of battles and essentially eliminating them as a power, taking direct control of the provinces. The Urakami had apparently expected Nobunaga to dispatch forces to aid them, but he had erred on the side of caution, deciding that the Urakami were an acceptable sacrifice for keeping the peace with the Mori, at least for now.

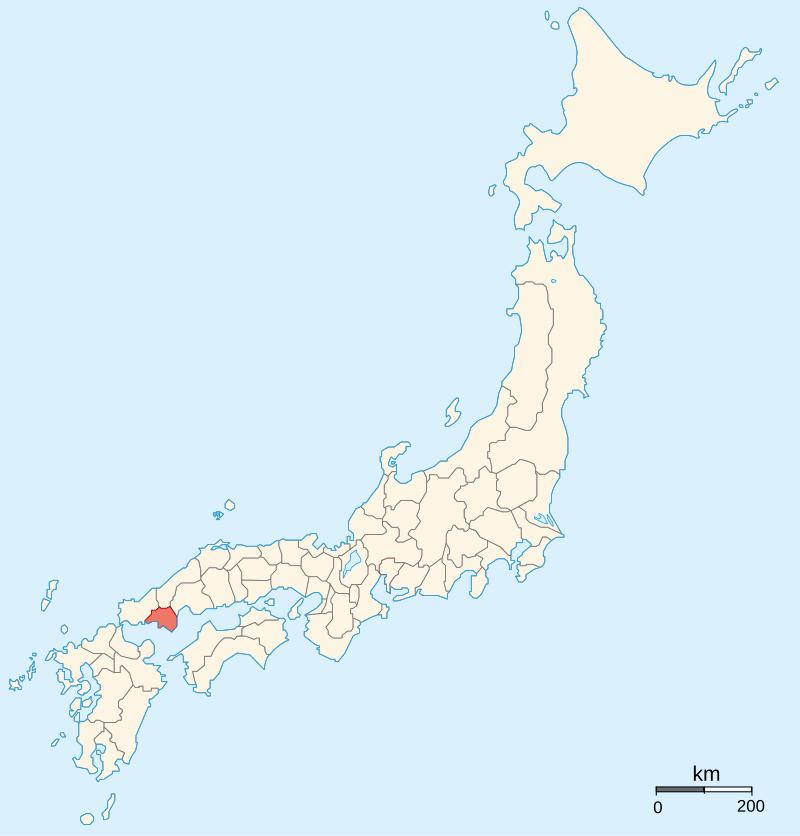

An immediate consequence of this was that there were no more buffers between the Mori and Oda territories, which now shared a border. The relationship was already tense, and it only grew worse as both sides became involved in Tajima Province. Expecting that Nobunaga would seek to make the province part of his domain, Terumoto made an alliance with the province’s local power, the Yamana. You may remember that name from earlier posts, and well done if you did; the Yamana were still around at this point, though no longer the great clan they once were.

By Alvin Lee – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39200929

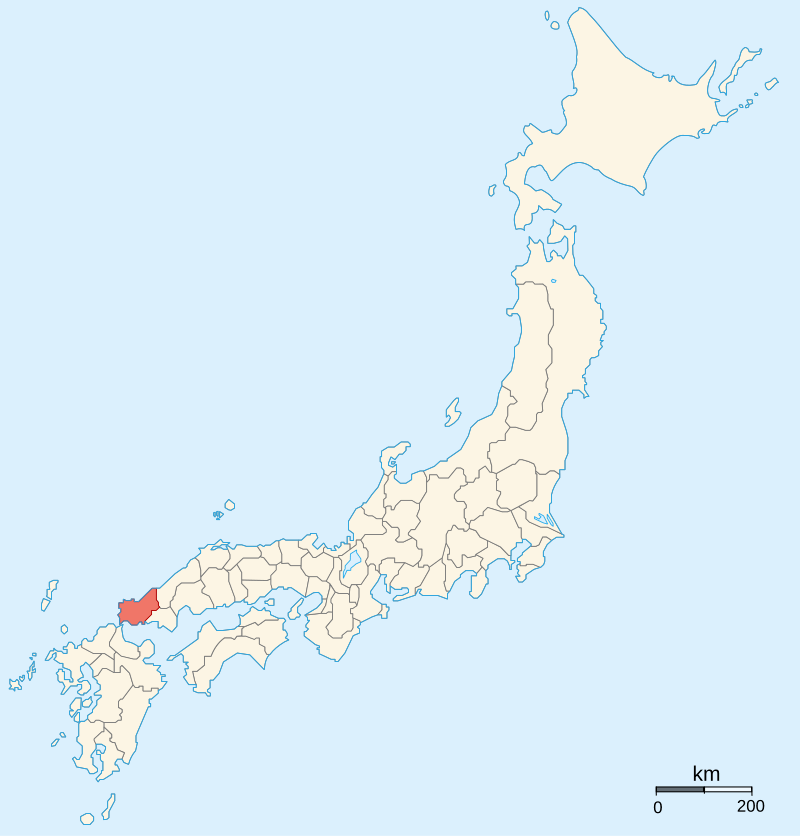

Then in 1576, the Shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiaki, having been forced to flee Kyoto by Nobunaga, found himself in Bingo Province, controlled by the Mori. Terumoto was not happy about this. Although he had ostensibly supported the restoration of the Shogunate, he understood that the only way that could happen was through war with Nobunaga, which he had no interest in. When the Shogun showed up on his doorstep and formally asked the Mori to support him in returning to Kyoto, then Terumoto was in a tricky spot.

The Mori had promised Nobunaga that they would not harbour the exiled Shogun. On the other hand, Nobunaga had taken actions that were widely seen as trying to undermine Mori power, and although he had attacked them directly, the damage had been done.

Terumoto, for his part, took a long time making up his mind. We’ll never know exactly what he was thinking, but it’s easy to imagine that Terumoto had plenty of reason to be wary of Nobunaga, who had already meddled in Mori affairs and would probably do so again if given the chance. The Mori were also one of the few clans with the power to actually face Nobunaga directly, something that Terumoto must have been aware of.

Terumoto would declare for the Shogun in May 1576, effectively ending his alliance with Nobunaga and setting the Mori on a collision course with the Oda, but more on that next time.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AF%9B%E5%88%A9%E8%BC%9D%E5%85%83

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C5%8Dri_Terumoto

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%9C%88%E5%B1%B1%E5%AF%8C%E7%94%B0%E5%9F%8E

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%A7%87%E5%B3%B6%E5%9F%8E%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%9C%B1%E5%8D%B0%E7%8A%B6

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oda_Nobunaga

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashikaga_Yoshiaki