“The bureaucracy is expanding to meet the needs of the expanding bureaucracy.” – Oscar Wilde

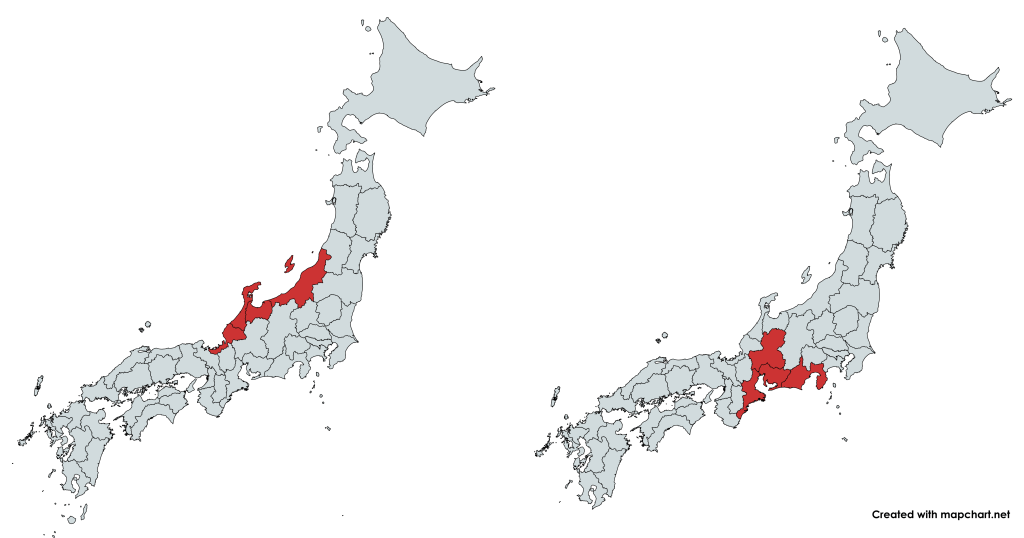

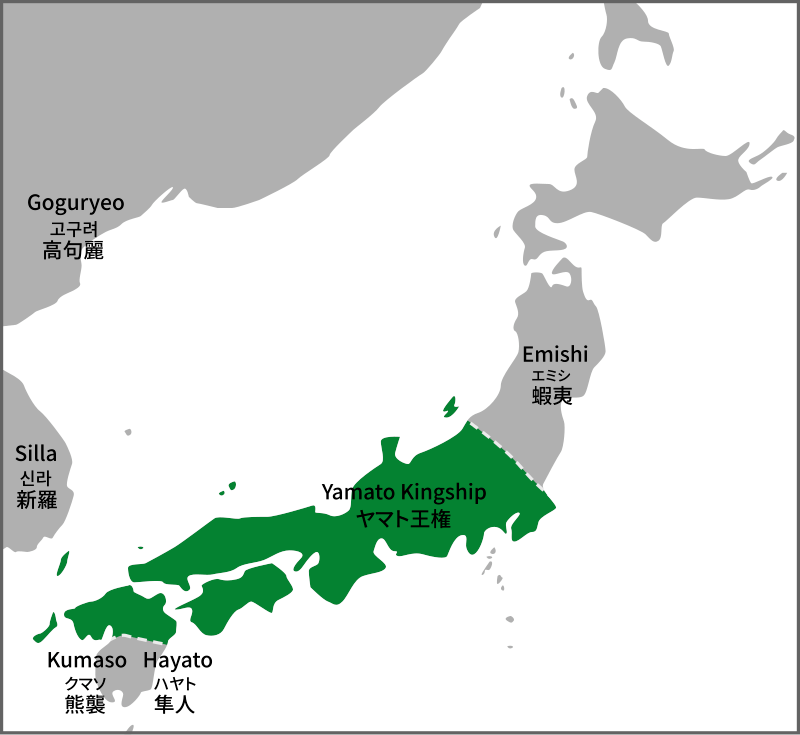

By the mid-6th century, the Yamato state had undergone a period of extensive centralisation, and although they didn’t rule the entirety of what we now call Japan, they came to control the largest state the land had yet seen.

By Samhanin – Own work, source: Yamato ja.png, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=121731575

We briefly discussed the emergence of monarchy last time, but to recap, during the early Yayoi Period, settlements became larger and more sophisticated, leading to the rise of formal power structures. Chinese sources from the time also make mention of specific Kings and Queens from the lands of “Wa” (their name for Japan).

Traditional Japanese historiography tells us that the first ‘Emperor’ of Japan was Jimmu, who is supposed to have ruled from 660-585 BC. Jimmu was the great-great-grandson of the sun goddess Amaterasu and lived for about 126 years, which isn’t all that impressive if you consider his divine origins.

Most scholars agree that Jimmu and the following 28 Emperors were legendary figures. However, there is evidence to suggest that the 21st Yuryaku (r. 456-479) really existed, though it isn’t until Emperor Kinmei, who took the throne in 540, that we have a ruler who is considered genuinely historical.

The other issue is that we shouldn’t really call these early rulers ‘Emperor’ at all. The title Tenno (literally meaning Heavenly Sovereign) wasn’t used until the 7th century when it was also applied retroactively. Before that, the rulers of the Yamato state were referred to as Okimi (translated as Great King).

Heavenly Origins

So why the change? Well, like almost everything else at that time, it was because of China. Since around 1000 BC, the Chinese Emperor was referred to as the Son of Heaven, and each Dynasty drew legitimacy by having the Mandate of Heaven. Even though Chinese Dynasties rose and fell all the time, each new ruler would take the title of Son of Heaven and claim the mandate for himself.

The early Yamato rulers saw this and thought they’d get in on the act. After all, if claiming divine origins worked for China, why not for Japan? So, the Great King became the Heavenly Sovereign. The difference (which will become important later) was that the newly dubbed “Emperor” of Yamato didn’t rule by Divine Mandate; he was said to be a literal son of heaven, descended from Amaterasu, with his rule legitimised by his divine bloodline.

As settlements grew and powerful families emerged, they would join together with others (willingly or not), leading to proto-states that centred around one or a small number of powerful local families, which would, in turn, be absorbed or conquered by more powerful neighbours.

While the exact details of this process of conquest and consolidation aren’t entirely clear, later (often legendary) sources make reference to military campaigns uniting the lands around modern-day Nara, which would become the centre of the later Yamato state.

Although these sources (the Nihon Shoki and Kojiki) aren’t reliable histories in the academic sense, they do suggest a cultural memory of war and conquest, which means it isn’t too much of a stretch to imagine that the original rulers were highly successful militarily.

Game of Thrones

The rule of Emperor Kinmei (the first historical Emperor) coincided with the arrival and gradual spread of Buddhism in Japan. Now, we’ll discuss the ‘Buddhaisation’ of Japan at a later date, but the short version is that Buddhism is said to have officially arrived in Japan in 552 when the King of Baekje (a Korean kingdom) sent a statue of the Buddha to the Yamato Court.

Other sources say that Buddhism actually arrived in Japan in 538, but either way, this new religion caused a deep rift to form between the two most powerful families at court, the Soga and the Mononobe.

The Soga were supporters of Buddhism, and they had the advantage at court. The Emperor had two Soga wives, and his father-in-law, Soga no Iname, was the first Omi, a title which suggests power second only to the King (Okimi). However, when Emperor Kinmei died, his non-Soga son, Bidatsu, was selected to succeed him. Bidatsu’s rule would be marked by the ongoing conflict around Buddhism, as the Soga were violently opposed by the Mononobe, advocates of Japan’s traditional religion (Shinto).

Bidatsu died in 585 (maybe of Smallpox), and another power struggle broke out. The Soga, now led by Imane’s son, Umako, were victorious, and their candidate was enthroned as Emperor Yomei.

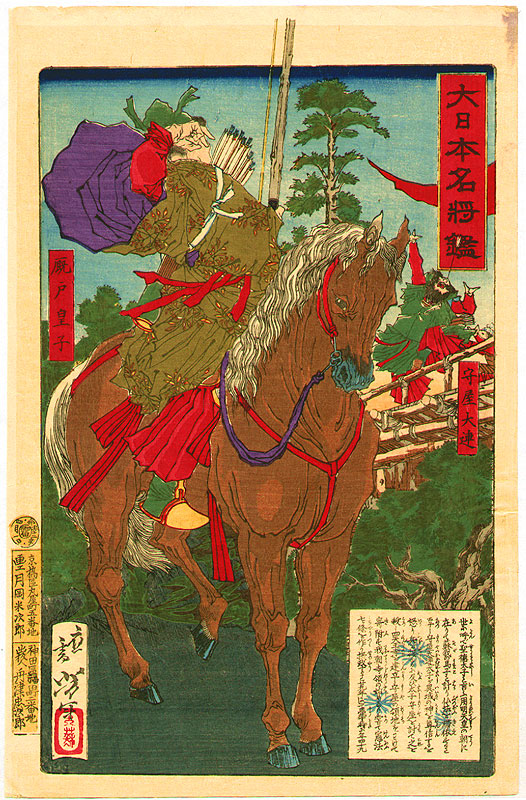

That might have been the end of it, but Yomei ruled for less than two years, and upon his death, both sides went at it again. The resulting conflict took place in early July 587, and the Mononobe were initially successful, driving the Soga back in a series of minor battles until they were caught in the area around Mt Shigi.

At this point, the leader of the Soga forces, Prince Shotoku, is supposed to have promised to build a temple on the site of the battle if they were victorious. This apparently did it, and the Soga turned things around, defeating the Mononobe. The resulting defeat led to the deaths of most of the Mononobe leadership, and their power at court was broken.

The Soga spent the next 60 years effectively unchallenged as the power behind the throne. They controlled the court through political acumen and intimidation and secured their influence over the Throne by ensuring the reigning monarch was either a member of the Soga Clan or a descendant of one.

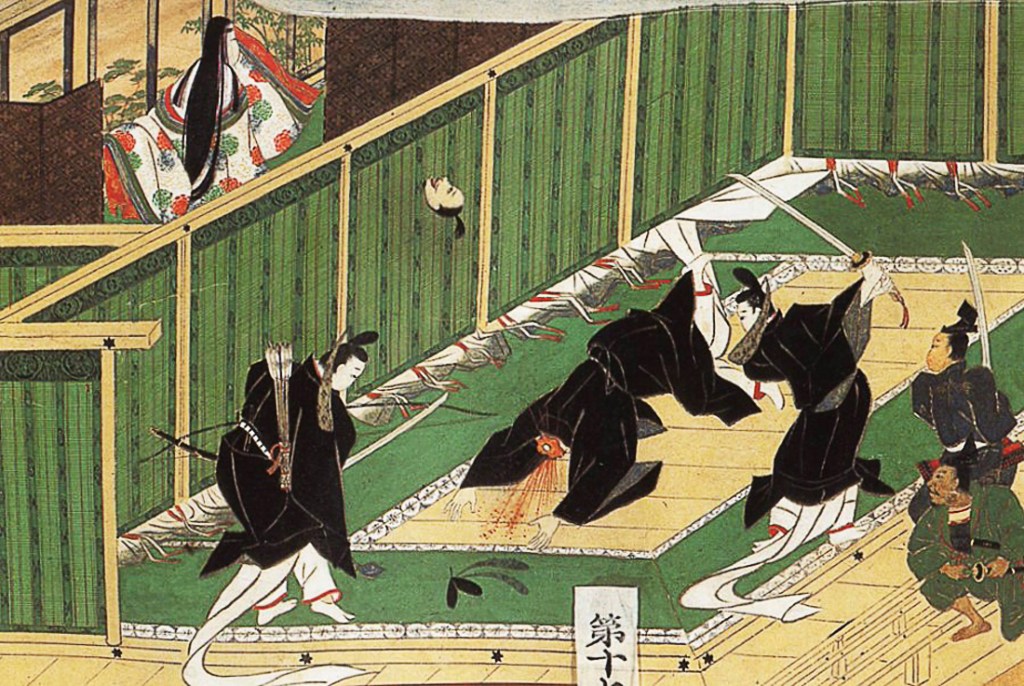

It’s tough at the top, though, and Soga dominance generated deep resentment amongst the other noble clans, and members of the Imperial Family itself. In July 645, a conspiracy, set into motion by Prince Naka no Oe (later Emperor Tenji) and Nakatomi no Kamatari (the founder of the Fujiwara Clan, who will become really important later), ended with the assassination of Soga no Iruka, and the suicide of his father, Soga no Emishi. The so-called Isshi Incident (named for the year it happened) broke the power of the Soga and led to the re-establishment of royal power.

Imperial Reform

In the immediate aftermath of the Isshi Incident, Empress Kogyoku abdicated, and Emperor Kotoku (not her son) ascended the throne on the insistence of the conspirators. Kotoku and his supporters set about reforming the royal government with the intention of centralising and enhancing the power of the throne.

Given that China had been the source of culture and religion, it is perhaps no surprise to find out that reformers looked there for inspiration; in fact, most of the new systems put in place in Japan at that time were direct copies of those already in use in China.

Now, when we speak of ‘reform,’ we should remember that we’re not talking about a single reform but actually a series of laws, proclamations, and modifications over many years, leading to the system of administration known as Ritsuryo.

Ritsuryo as a term is made up of two words, Ritsu, meaning a criminal code, and Ryo, meaning an administrative one, and there was no single Ritsuryo ‘Code’. Rather, the system was defined by a series of law codes issued between 669 and 757, which followed on from and built on each other over time.

The actual law codes unfortunately no longer exist (and they’d likely make for fairly dull reading besides), so below is a broad summary of what the reforms actually were.

Land Reform

As we mentioned earlier, the power of the nobility came from their control of fortified settlements and the lands that surrounded them. So, how do you deal with that? Simple, take control of all the land. Some of the earliest reforms dealt with land reform, dividing Japan into provinces, and organising surveys (supposed to take place every six years) for the purposes of taxation and conscription.

Land was also nationalised, but before you get the idea that this was some egalitarian attempt at land redistribution, ‘nationalised’ in this context means ‘belongs to the King’. It was the Court that decided who got what land, and each province was ruled by a governor appointed by and answerable only to the King.

Taxation and Conscription (for both labour and military service) were formalised based on the Chinese model, with everyone expected to either pay their share or serve their time in the army or on royal construction projects.

The royal capital was established at Nara, and a new city, based on the Chinese capital at Xian, was built (previously, the capital had been wherever the King was.)

New Government

As for the word ‘King’, from now on, the King would be an Emperor, and the previous system of government was now to be based on the Chinese model, too, with some notable exceptions.

Firstly, there was the division of government into different departments. The two major offices were the Jingi-kan, which was responsible for religious matters, and the Daijo-kan, which was further subdivided into eight departments that dealt with actually running the state.

There was also the establishment of a formal system of ranks for the nobility. Divided into nine ranks, which were then subdivided into four (with the exception of the top three, which only had two sub-divisions). Each rank carried an increased prestige and a larger salary, another novelty which was supposed to tie the nobility closer to the throne, as it was the monarch who now dispensed wealth and title.

Although practically a direct copy of Chinese law, there were exceptions or adaptations to Ritsuryo. There were two that would prove to be significant in the long term. First, as we mentioned earlier, the newly dubbed Emperor did not hold the Mandate of Heaven as his Chinese counterpart did. Instead, he was the literal son of heaven, a status that could not be transferred or lost. This had the convenient side effect of meaning that a Japanese Emperor could not be overthrown and replaced by a ‘new’ dynasty.

Secondly, the Imperial Rank system in China was (at least in theory) based on merit, with the famous Imperial Examinations ensuring that only the best and brightest could gain prestigious positions. The Japanese, however, limited access to formal rank to offspring of noble families, ensuring that the same clans would, over time, come to dominate certain departments of the government and eventually, the throne itself.

Law & Order

As the reforms sought to centralise control of land and title, so to did they seek to impose rigid control on wider Yamato society. The new provinces were now to be overseen by governors appointed by the court, taking the application of law out of the hands of powerful local families (at least in theory.) The new Imperial Court also reserved the right of appeal for itself; now (also in theory), anyone could petition the Emperor about injustice in their local area.

Along with the ‘nationalisation’ of land, the common people, too, became the direct subjects of the Emperor. Whilst technically removing them from the local dominance of the nobility, the system was no liberation of the people.

On the one hand, the land reform directly benefited common people, as every citizen was now entitled to a certain amount of land, which they could own for their lifetime, and would be taxed according to crop yield. However, upon their death, the land would return to the ownership of the state and couldn’t be passed on to children. Additionally, women were only entitled to 2/3 the land of men.

There was also the matter of the caste system. Everyone was divided into one of two castes, the Ryomin or the Senmin. Each caste was further divided (four for Ryomin, Five for Senmin), and there were clear distinctions. Ryomin were made up of the ruling class, the wealthy, and those involved in court functions. The Senmin, very broadly, were subservient to the Ryomin, with the bottom two levels, the Kunuhi and Shinuhi being slaves. It was perhaps slightly better to be a Kunuhi since they were slaves at court instead of out in the countryside, but I imagine the distinction was pretty meaningless to the slaves themselves.

There was some mobility within the caste system, with slaves being able to earn freedom and Ryomin being reduced to Senmin status for certain crimes, but overall, it was a fairly rigid system, at least at first.

On the subject of crime, the reforms established a five-tier system of punishment, with caning being the most minor, escalating to execution (either by hanging or beheading) for serious crimes, and speaking of really serious crimes, the reform took the Ten Abominations of the Chinese legal code and reduced them to eight.

So, while things like Rebellion, Murder, and a lack of filial piety (respect for your parents) could get you beheaded, the Japanese dropped the rules about familiar discord and, for some reason, incest.

Trouble ahead.

The reforms were intended to centralise and formalise Imperial rule in Japan on the same basis as the Chinese system, and in the short term, it was pretty successful. Land distribution meant a steady tax base, and conscription meant that military power was focused in the hands of the Emperor rather than regional strongmen.

But the reforms had unwittingly sowed the seeds of the eventual downfall of Imperial authority. By concentrating political power in the hands of the nobility rather than a merit-based bureaucracy, powerful families would come to dominate the levers of power and the Emperor himself.

Land reform, too, would backfire. Initially, citizens were forbidden from bringing new land into cultivation, but as the population expanded, the agricultural base failed to keep up. Changes were made, and the people were permitted to claim new land for themselves as long as they cultivated it themselves.

Although a well-meanimg attempt to grow the food supply, what actually happened was powerful local families, with resources and manpower, snapped up the good land, and when the law was changed to allow for land to be inherited by three generations (and eventually without limit) the seeds were literally sown for a powerful, land-based aristocracy, far from, and no longer under the control of the Imperial Court.

Ooooh, foreshadowing…

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taika_Reform

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_emperors_of_Japan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emperor_Jimmu

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emperor_of_Japan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yatagarasu

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asuka_period

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isshi_incident

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emperor_Kinmei

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soga_no_Iname

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soga%E2%80%93Mononobe_conflict

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emperor_Bidatsu

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emperor_Y%C5%8Dmei

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taih%C5%8D_Code

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ritsury%C5%8D

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Department_of_Divinities

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daij%C5%8D-kan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Provinces_of_Japan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_castes_under_the_Ritsury%C5%8D

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ritsury%C5%8D