By the mid-15th Century, Japan was in trouble. That might not come as a surprise for anyone who has read any of my previous posts (or even cast a curious eye over Japanese history to this point), but even by the admittedly tumultuous standards of Shogunate rule, things were bad.

We’ve focused a lot on the Ashikaga Shogunate and its ongoing efforts to stamp permanent authority on the country, but if we zoom out for a moment, the chaos is evident in microcosm almost everywhere we look.

There are multiple, long-term reasons for this, but here are several immediate causes: First, the Shogun’s policy of insisting that shugo (provincial lords) permanently reside in Kyoto. Whilst this kept the highest rank of the nobility under close supervision, it also meant that governance of the provinces was left in the hands of deputies, and over the years, these deputies began to operate more or less independently, and not always (if ever) in the interests of their nominal lords in Kyoto, leading to centralisation on paper, but fragmentation in reality.

Secondly, the nature of Samurai families meant that there was no clear rule of succession. Whilst a lord could be succeeded by his eldest son, in reality, when a lord died, it wasn’t uncommon for any of his relatives who could muster support to stake a claim, leading to frequent outbreaks of serious violence that sometimes lasted for years, and led to even more fragments forming.

Thirdly, the Ashikaga Shoguns themselves were weak. Since the beginning of their Shogunate, they had relied almost entirely on the support and goodwill of powerful clans. The reasons for this are fairly straightforward. In Japan, as in most feudal societies, power was derived from wealth and manpower, and those were derived from the control of land.

The Ashikaga, despite being the pre-eminent family, controlled very little land of their own, and therefore had relatively few independent resources that they could call on, meaning that, when it came to everything from collecting taxes to raising armies, they relied heavily on the powerful clans around Kyoto.

This system was always unstable, but it kind of worked when there was a strong-willed, capable Shogun at the head of things. But what happened when the seat of power was occupied by a weakling, or worse, a child?

In 1441, that question was foremost in the minds of Japan’s leaders. In June of that year, the Shogun, Ashikaga Yoshinori, was assassinated. Yoshinori has arguably become a paranoid despot by this point, but he was undeniably a leader strong enough to hold the whole system together.

The impact of his sudden death was compounded by the fact that he had no adult heirs. Now, as I mentioned earlier, the idea that a lord would be succeeded by his eldest wasn’t enshrined in law, but the heir, generally, was expected to at least be grown up. What remained of the Shogunate was now facing not only rebellion but a succession crisis as well.

The crisis was faced by the Kanrei, or Shogun’s Deputy, Hosokawa Mochiyuki. You might remember hearing the Hosokawa name before. They were a powerful family, and although their fortunes waxed and waned, they had remained central to the Shogun’s government.

Mochiyuki put Yoshikatsu, the previous Shogun’s son, on the throne, and for a short while, at least, the initial crisis passed. Emphasis on the short , however, within a year, first Mochiyuki, and then Yoshikatsu (at just nine years old) were dead.

Mochiyuki was replaced as kanrei by Hatakeyama Mochikuni, a member of the Hatakeyama Clan (hence the name). The Hatakeyama had been particularly harmed by the tyrannical rule of Ashikaga Yoshinori, and Mochiyuki sought to use his position to undo some of that harm. His intention was to restore certain lands and titles that had been taken from himself and his relatives, which I suppose he thought would serve to redress the balance of power.

In this, however, he was opposed by the Hosokawa Clan, who had actually done quite well under Shogun Yoshinori and saw no reason to upset the new status quo. What followed was something of a ‘Cold War’ situation in which the Hosokawa and Hatakeyama would seek influence and advantage by engaging in politicking and proxy wars.

The most visible example of this is how they involved themselves in family disputes. As I mentioned, succession was not a clear-cut thing, and when violent disputes inevitably broke out, the Hosokawa and Hatakeyama would swoop in to offer support for either side.

From 1455 to 1460, the Hatakeyama themselves fell into civil war over who would be the next leader of the clan. The Shogun threw his support behind his favoured candidate, but it did little good.

A strong Shogun might have been able to reassert control, but Yoshimasa was not that, and Shogunate support, which might have once been a decisive factor in deciding these disputes, instead became an irrelevance.

One of the more serious outbreaks was in the Kanto (again), and when the Shogun ordered the Shiba Clan to dispatch an army to put it down, the Shiba instead collapsed into chaotic infighting over who would be the next head of the clan. The Shogun attempted to impose a new clan head, but this just made things worse. The Shiba were now too embroiled in their own fighting to be much use, and the rebellion in the Kanto went on unopposed.

By late 1464, then, Japan was in serious crisis. This sense of anxiety was only worsened by the fact that, at age 29 (middle-aged by the standards of the day), Yoshimasa had no children who could serve as his heir (he had two daughters, but no one thought a woman could be Shogun). In November of that year, he solved this problem by calling his brother, Yoshimi, who was a monk, back to secular life and named him his heir.

With Yoshimi safely back in Kyoto, the question of succession was resolved for now, and the Shogunate could focus on bringing the rest of the country back under control, or so they probably thought.

In November 1465, just a year later, and to the surprise of many (though hopefully not Yoshimasa), a son and heir, Yoshihisa, was born. I’ve made this point already, but a son didn’t necessarily inherit from his father, and Yoshihisa didn’t automatically become the heir.

This is where Yoshihisa’s mother, Hino Tomiko, enters the scene. She had actually been Yoshimasa’s wife for a decade at that point, and had given birth to a son in 1459, although the child had only lived for a day. Two daughters followed in 1462 and 1463, and then in 1465, Yoshihisa arrived.

Like many historical women, Tomiko has been the victim of some seriously unflattering portrayals in contemporary sources, and what followed is possibly an example of that. The Oninki, a source for the origins of what was to come, say that Tomiko was a manipulative woman who saw in her son an opportunity to take power. She secured the support of the Yamana Clan and sought to promote her son as heir, whilst she would take control as regent until he came of age (which was expected to be a long time).

Her alliance with the Yamana and her attempts to promote her son as heir over the Shogun’s brother were, for centuries, believed to have been the spark that led to the so-called Onin War.

The problem with this is that the Oninki is literally the only source that places the blame for the war on Tomiko and her scheming. That’s not to say that she didn’t play a part, and the factions that formed in the late 1460s were certainly motivated at least nominally by support for one candidate or another, but Tomiko herself seems to have become a genuinely unpopular figure by the late 15th century (fairly or not) and so the Oninki which is usually believed to have been authored around the late 15th or early 16th centuries may have just been playing on what was, by then, a popular trope.

Outside of Kyoto, the situation continued to deteriorate. In July 1466, the Shogun attempted to intervene in the Shiba clan’s succession crisis. This time, however, he encountered serious pushback, with several powerful shugo, including the Hosokawa, refusing orders to intervene, and some even stating they would fight for the Shiba against the Shogun.

In September of that year, rumours abounded that Yoshimi (still officially the heir at this point) was going to be assassinated. Exactly how complicit the Shogun was is unclear, but Yoshimi was sufficiently scared for his life to flee to the protection of the Hosokawa.

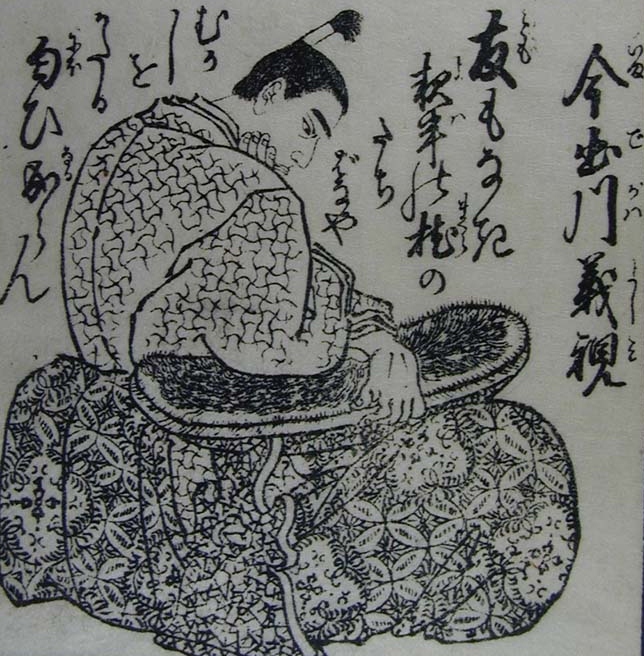

Musuketeer.3 – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24843648による

At this point, the Hosokawa and the Yamana cooperated to protect Yoshimi and oppose the Shogun. Facing the combined might of these two clans, the Shogun had little choice but to back down. The allies went further when they demanded that the lords who were closest to the Shogun (and were publicly blamed for his decisions) be removed. Several previously powerful supporters of the Shogun were either forced to commit suicide or sent into exile, seriously weakening the ability of the Shogun to run the government, and effectively leaving him in the hands of the Hosokawa-Yamana alliance.

This alliance of convenience quickly became inconvenient, however. It goes back to the Hatakeyama Clan’s internal dispute that I mentioned earlier. The Hosokawa and Yamana supported rival factions, and when this dispute spilt over into Kyoto, a proverbial line in the sand was drawn.

The actual combatants were made up of various members of different clans, and it gets very messy, so for ease of use, we’ll just talk about the Hosokawa and Yamana factions, but just know that’s not strictly how it went. For example, there were Hatakeyama, Shiba, and numerous other clans on both sides, which gives you some idea of how chaotic it got.

At New Year 1467, the Shogun, breaking with tradition, visited the Yamana faction for the celebrations, which was about as clear a statement of support as you can imagine short of openly declaring himself. In response, Hosokawa forces surrounded the Shogun’s palace and attempted to intimidate him into issuing orders against the Yamana faction.

This attempt failed, however, and the Shogun then issued orders that private feuds should not be settled in Kyoto. The Hosokawa faction seems to have followed these orders, but the Yamana and their supporters did not. As a result, the Hosokawa faction’s allies were forced to retreat to the Kamigoryo Shrine, on the outskirts of Kyoto.

There, on the evening of January 18th, 1467, they were attacked by allies of the Yamana faction and defeated. At the time, the Shogun intervened swiftly, and there was hope that what became called the Battle of Kamigoryo Shrine would be the end of it.

Neither side was going to let it lie, however, and throughout early spring, both sides gathered more forces in and around Kyoto, and by May, they were on a collision course.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%BF%9C%E4%BB%81%E3%81%AE%E4%B9%B1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%8A%E5%BE%A1%E9%9C%8A%E7%A5%9E%E7%A4%BE

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%BE%A1%E9%9C%8A%E5%90%88%E6%88%A6

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E8%A6%96

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%B4%B0%E5%B7%9D%E6%8C%81%E4%B9%8B

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%95%A0%E5%B1%B1%E6%8C%81%E5%9B%BD

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C5%8Cnin_War

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%97%A5%E9%87%8E%E5%AF%8C%E5%AD%90

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hino_Tomiko

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%BF%9C%E4%BB%81%E8%A8%98

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashikaga_Yoshimasa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashikaga_Yoshihisa

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E6%94%BF#%E6%96%87%E6%AD%A3%E3%81%AE%E6%94%BF%E5%A4%89