We’ve already talked about Imperial decline during the Heian Period. Over many centuries, central control eroded, until eventually the provinces proved to be ungovernable. Eventually, the power of the Imperial Court was usurped by Minamoto no Yoritomo, who established the Kamakura Shogunate in Kamakura, obviously.

You may not be surprised to hear that the Emperor wasn’t best pleased with this turn of events. Although the actual power of the Emperor had been largely theoretical for decades, there had always been a veneer of ‘Imperial’ authority. The rise of the first Shogunate, however, did away with that.

With supreme military power firmly in Yoritomo’s hands, there was little the Emperor could do to change the status quo. However, as we’ve discussed, Yoritomo’s heirs proved not to be the model of their father. By the dawn of the 13th Century, the Kamakura ‘Shogunate’ was in fact ruled by regents, or Shikken, from the Hojo Clan.

In 1219, the regent was Hojo Yoshitoki, who shared power with his influential sister Hojo Masako, the so-called ‘Nun Shogun’. That year, Masako’s son, Sanemoto, the third Shogun, was assassinated, bringing an end to the line of Minamoto Shoguns (Yoritomo and his two sons). Although the Hojo were already in effective control, the end of the ‘legitimate’ line of Shoguns presented an apparent opportunity for their enemies to challenge them.

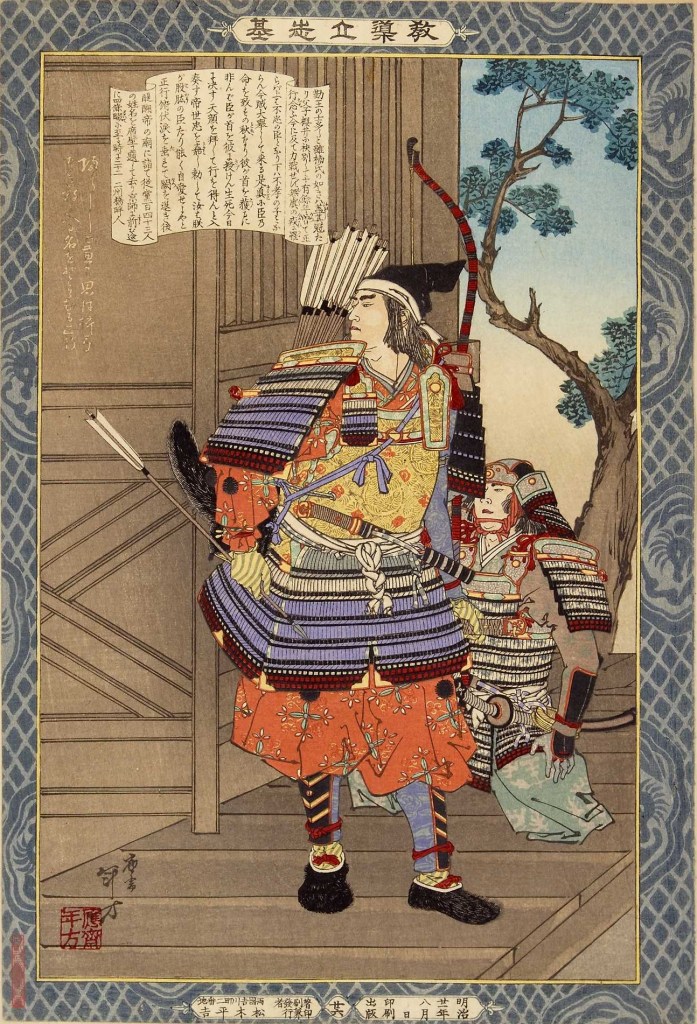

Emperor Go-Toba

In a period where Emperors were often well-decorated figureheads, Go-Toba stood out. He was highly educated, as most courtiers were, but he had also shown skill at martial arts, earning him respect and loyalty from warrior families in the west and north. Unfortunately for him, the Throne still drew its income from its land holdings, and when the Shogunate appointed officials to oversee those holdings, the money taken in taxes often didn’t find its way to the Emperor.

After Sanemoto’s assassination in 1219, the Hojo approached Go-Toba about the possibility of one of the Emperor’s sons becoming the next Shogun. Go-Toba attempted to negotiate, seeking the removal of Shogunate officials from Imperial holdings.

The Shogunate sent a force of 1000 men under Yoshitoki’s brother in an attempt to intimidate the Emperor. Go-Toba wasn’t easily scared, however, and negotiations broke down, although the Emperor would offer a concession; he would allow a member of the Imperial family to become Shogun, as long as it wasn’t a prince of the main royal line.

The Hojo were satisfied with this, and Kujo Yoritsune, who was only a little over a year old, was chosen as the fourth Shogun. However, because Yoritsune was a baby, the position of the Hojo as regents was secure, and, for a time at least, peace endured.

The elevation of a member of the Imperial house to the position of Shogun did nothing about the underlying issues, however, and in July 1219, just a few months after the previous negotiations, the military governor of the area around Kyoto, (who had been appointed by the Shogun) was attacked and killed by warriors acting on the Emperor’s orders.

Some records say that the governor had been planning to launch a coup and make himself Shogun, with Go-Toba, made aware of the plot, acting to stop the plot before it came to fruition. Other sources, however, point out how unlikely it is for Go-Toba to have had a Shogunate official killed as a favour to the Shogun, and it is more likely that the governor either discovered, or was made aware of, the Emperor’s plans, and was removed accordingly.

The unfortunate fellow apparently took his own life when his residence (which was within the grounds of the Imperial Palace) was surrounded and burned by Imperial loyalists, and whatever the reasons, this was a direct attack by forces representing the Emperor on those representing the Shogun. The Emperor then asked the Shogunate, Court Officials, and local temples and shrines to donate money to help rebuild the burned residence, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, most of them refused to pay up.

During rebuilding work, rumours spread that Go-Toba was quietly gathering allies and raising an army. It was also alleged that he had asked shrines and temples around the capital to invoke the power of the gods on the Emperor’s behalf, which was quite the provocation, apparently.

War Begins

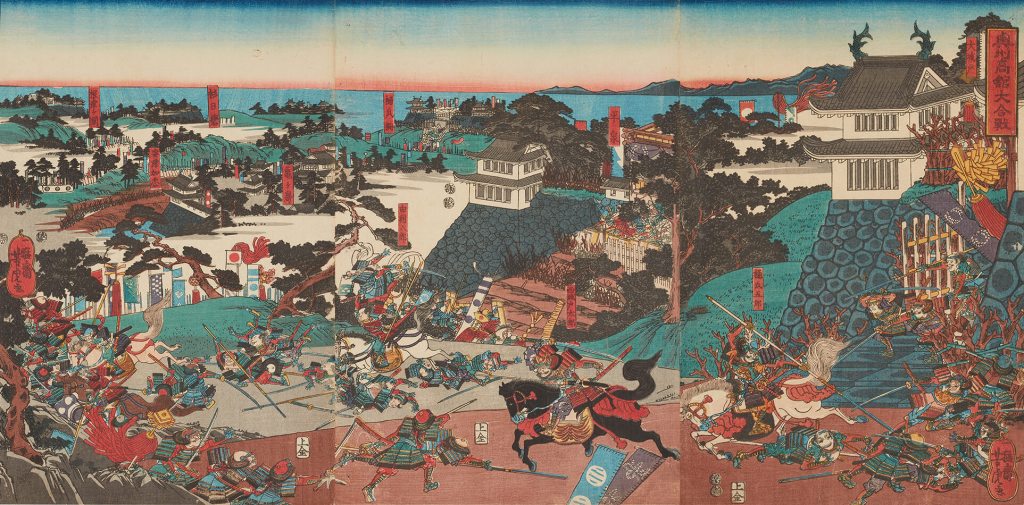

Then, in Spring 1221, Go-Toba gathered troops in the capital under the pretext of protecting religious sites and ceremonies. On May 15th, he dropped the pretext; however, when forces loyal to the Imperial Side attacked the offices of the Shogun in Kyoto, burning them and killing the officials, which, as declarations of war go, is pretty definitive.

On the same day, Go-Toba issued a formal Imperial decree, ordering all the warriors of the nation to arrest Yoshitoki, who was declared an outlaw and enemy of the court. Within a few days, warriors from across western Japan had risen against the Shogun, and Go-Toba believed, rather flippantly, that the issuance of an Imperial decree would fatally undermine the Shogunate.

This is one of those times that later writers absolutely love to dramatise. It’s all honour, loyalty, duty unto death, etc. but the reality is that, despite an Imperial Decree, and a counter-decree from Hojo Masako, the majority of the warriors across the nation (those who were directly tied to either side through blood or obligation) sided with whoever they thought would benefit them the most if they won.

In those calculations, the Shogunate had the advantage; the Shogun had the right to distribute land, and most of the warrior families expected to be rewarded with the lands and titles of those who had sided with the Emperor and the court, who was generally believed to have been likely to favour himself and his courtiers, in the event of their victory.

So, for all their vaunted ‘honour’, the Samurai would (and not for the last time) side with those they thought would give them the best deal, and by the time they marched, the armies loyal to the Shogun are said to have numbered nearly 200,000.

The Shogunate army was actually three separate forces, with 40,000 men heading by a northern route, another force of 50,000 heading through the mountains, and the third, largest force of 100,000, following the main Tokaido Road, with all three marching on Kyoto.

The Imperial side seems to have been caught off guard by first the size, then the speed of the Shogunate forces. It appears that the Emperor had believed his decree would be enough to secure mass defections, and when the opposite occurred, the forces loyal to the throne were out of position and hugely outnumbered.

Resistance was scattered and ineffective, with some sources suggesting that the main army took just 22 days to complete the march from Kamakura to Kyoto, which might be an exaggeration, but goes some way to highlighting how badly prepared the Imperial Army was.

Though the court was able to gather warriors from Western Japan, the numbers were nowhere near what they had expected, and besides, the rapid advance of the Shogunate army meant that reinforcements wouldn’t have been able to reach the capital in time.

In desperation, Go-Toba went to Mt Hiei, on the outskirts of Kyoto, and pleaded with the famed warrior monks for support. The monks, partly out of opposition to the Emperor, and partly due to their fear of the strength of the Shogun, refused to help, and Go-Toba was left with an army of around 18,000 to defend the capital.

Outnumbered 5 to 1, Imperial forces took position near Uji, and on June 13th, another Battle of Uji (the third in 50 years) took place. Despite brave resistance, the Imperial side was overwhelmed, and on June 15th, Shogunate forces were in Kyoto. What followed was an orgy of violence, as the houses of Imperial officials and supporters were ransacked and burned, and the citizens suffered at the hands of the rampaging army.

As Kyoto burned, Go-Toba sent a message to the Shogunate army, withdrawing the Imperial order to arrest Yoshitoki, and blaming the whole thing on his ministers and advisors. Abandoned by the Emperor, some of his supporters fought on in vain, but the final defeat was inevitable, and by July, serious fighting was over, with a few fugitives evading capture until October.

In the aftermath, Go-Toba was exiled, and eventually replaced as Emperor by Go-Horikawa, and the estates of those who had been killed fighting for the Court, or proscribed afterwards, were distributed to the Shogun’s supporters. Direct control was established over Kyoto, and any semblance of independent military strength was ended; every warrior was now the direct vassal of the Emperor, or else.

The Shogunate also took control of the purse strings for the court. Prior to the war, the Emperor had held land in his own right and drawn income from it, but now, those lands were ruled directly by the Shogun, and the government in Kamakura could now decide how much, if any, cash the Emperor would get.

The end of the Jokyu War would mark the zenith of Shogunate, and therefore Hojo power, and for a time, they would rule more or less unchallenged, but some 60 years later, a new threat would emerge.

Since the dawn of the 13th Century, a previously fractured and quarrelsome people had been united under a single ruler and gone on to conquer an empire the likes of which had never been seen. Though this great conqueror was long dead, his sons and grandsons had continued his work, and in 1260, a new ruler was enthroned, one who would go on to make himself master of China and Korea before seeking new conquests across the sea.

In 1274, Kublai Khan, grandson of the Great Genghis, had ambitions to make himself master of the world, and he cast his eyes on Japan.

The Mongols were coming.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%89%BF%E4%B9%85%E3%81%AE%E4%B9%B1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kamakura_shogunate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Azuma_Kagami

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J%C5%8Dky%C5%AB_War

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emperor_Go-Toba

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%BE%8C%E9%B3%A5%E7%BE%BD%E5%A4%A9%E7%9A%87