So, in our last two looks at Heian Japan, we discussed the decline of Imperial power in the provinces, as the regional nobility gained control of the military and then economic power, leaving the Imperial court effectively impotent.

So, what was actually going on at court while the power was slipping away? Well, what usually happens when you have an isolated mini-community of hyper-privileged, completely out of touch, trust fund babies?

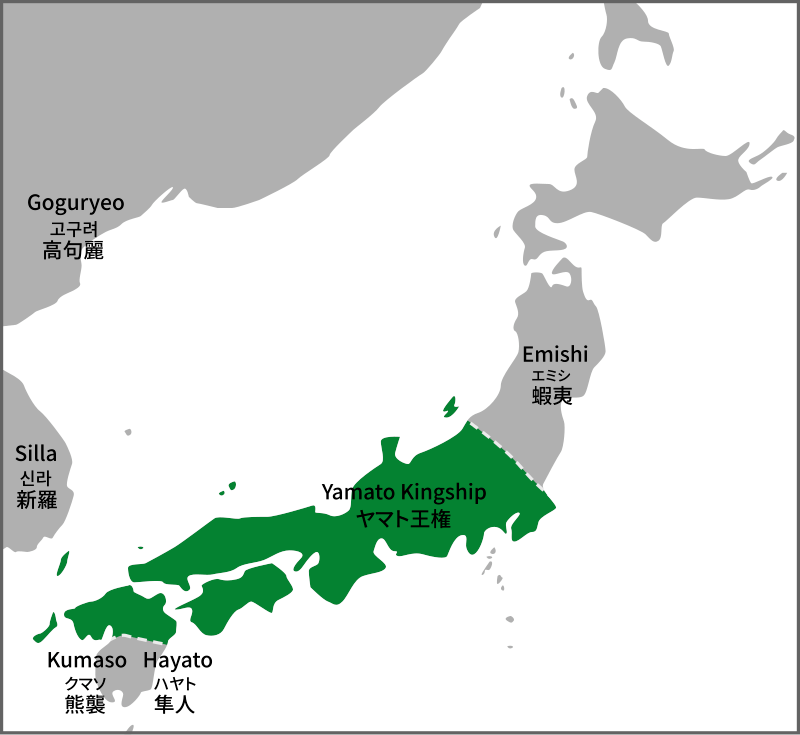

While trust funds obviously didn’t exist in 9th-century Japan, generational wealth absolutely did. The nobility at court was mostly made up of the descendants of the original Yamato families, those who had been the first to come to power in the area around modern Nara.

After the capital moved permanently to Heian-kyo, the noble families moved permanently, too. Some of these families had direct connections to the Imperial Family itself (real or fictional), which created a fairly insular community of people who busied themselves with court life at the expense of the rest of the nation.

We’ve already discussed the consequences of that, so we’re not going to focus too much on military or economic decline today, but needless to say, by the mid to late Heian Period, the court was completely out of touch with what was going on in the provinces, which eventually led to disaster.

Religion

Buddhism arrived in Japan in the 7th Century, brought in by Chinese and Korean scholars. Like most things imported at that time, Buddhism was largely just a copy of how things were done in China. However, by the Heian Period, a distinct “Japanese” culture was beginning to develop that had an impact on religion too.

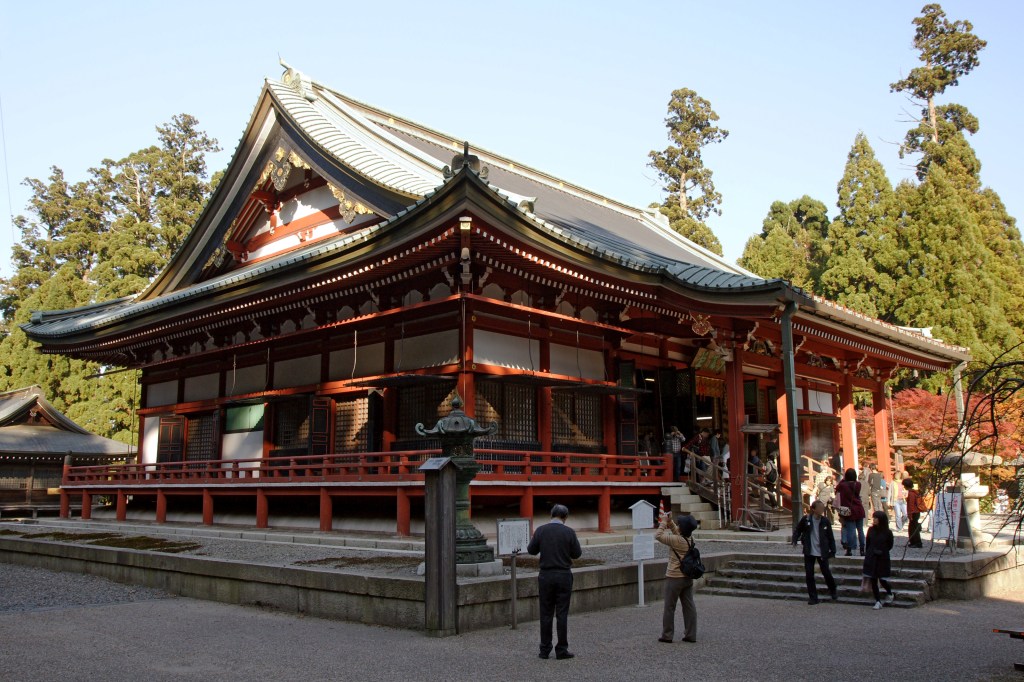

Two influential sects emerged around this time, Tendai and Shingon. Though founded by monks who had visited China, both branches integrated aspects of traditional Japanese religion into their philosophy. By the mid-Heian period, these sects had become politically influential, particularly the Tendai Sect, based at Mt Hiei, just outside Heian-kyo. There, monks were trained for up to 12 years, with the most promising being retained by the order and others taking up positions in the government, blurring the lines between religious and political power.

On a cultural level, Buddhism played a role not too dissimilar to that of the Catholic Church in Europe. Fantastic temples were constructed, and art, both in the form of painting and sculpture, flourished, sponsored by courtiers looking to curry favour with the increasingly powerful priesthood.

The Imperial Family and the aristocracy became tightly linked to the Buddhist Sects, with members of noble families often becoming high-ranking members of religious orders, and in turn, Monks, Priests, and Abbots became influential within the government. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, with the two sides so closely linked, that the temples would often preach in support of the Emperor and the status quo.

Over time, Buddhist Temples would become powerful political players in their own right, and their close association with the Imperial Court led to the image of Buddhism, or at least the organised Buddhist sects to be the religion of the aristocracy, whilst out in the provinces, more traditional Japanese beliefs held sway, further deepening the divide between the Emperor and his people.

A Novel Idea

Prior to the Heian Period, writing had been the preserve of noblemen and educated priests. The complex Chinese symbols (Kanji) took years to learn, and most people didn’t have access to education anyway. That began to change during this period. Firstly, the rise of wealthy, and more importantly, large temples, increased the number of people (men) with access to learning. Though still limited, these men would become a key part of the Imperial Bureaucracy.

The real trailblazers of Heian Literature weren’t priests and nobles, however, but women. As anyone who has ever tried to learn Japanese can tell you, Kanji are awful. There’s about six million of them, and they all have different pronunciations depend on context, mood, or the position of the stars, or something. The point is, Kanji are hard to learn now, and they were hard to learn back then, too, more so given how few people even had access to a textbook, let alone DuoLingo.

Fortunately, Kanji aren’t the only option when it comes to writing Japanese. Early on, Japanese scholars developed kana, a native script that made it easier to translate certain things into Japanese. As we’ve said, Kanji are hard enough to learn even with dedicated study, and given that women didn’t have dedicated study, the kana (divided into Hiragana and Katakana) were adopted instead.

Like most places before the 20th century, literacy in Heian Japan was extremely limited. Whilst this obviously meant there wasn’t a wide audience for poems and stories and such, it did lead to a highly specialised type of ‘courtly’ writing. Poetry, in particular, was a mark of good breeding, as was the quality of your handwriting.

This probably shouldn’t come as a surprise to us; after all, how often do we see politicians and celebrities mocked for their poor spelling and grammar? And don’t get me started on handwriting. Mine is ok now, in my mid-30s, but you’d have needed a scholar of ancient languages to decipher my writing when I was at school.

I digress; poetry and handwriting were important, is the point.

Poetry was probably the most common form of literature at the time. Poems would be written for all sorts of occasions, and it was said that a person’s poetry skills could make or break their reputation, which seems a bit extreme, but there you are.

Poetry was not the only form of literature available to the Heian Court. Stories in a form we would recognise as novels also appeared at this time, perhaps most famously the Tale of Genji, written sometime in the early 11th Century and attributed to Murasaki Shikibu (not her real name), a lady-in-waiting at the court.

She deserves a post of her own, but the short version is that she is generally accepted as the author of the story, although some scholars also suggest that the last ten chapters or so were written by someone else, possibly her daughter.

Heian Period literature can be a bit impenetrable by today’s standards; courtly culture at the time placed grade emphasis on innuendo, allusion, and almost obtuse vagueness. A great example of this is the fact that the Tale of Genji rarely, if ever, refers to characters by name. Although scholars agree that most of the characters are probably based on real people, it would have been unthinkable for a writer at the time to do something as crass as using a person’s name, even in fiction.

This, and a highly stylised form of writing, means that works like the Tale are often viewed by modern Japanese in the same way that a modern English-speaking person might see the works of Shakespeare, something that is fundamentally intelligible but is full of language that has long since fallen out of use, leaving us with metaphors that are open to interpretation, to say the least.

12 Layers

Fashion and Beauty were as central to the Heian Court as they are to the rich and famous today. Whilst at its core, fashion was about showing off wealth and status (as it is today), the Heian Court had some very unique ideas about what constituted beauty.

First, the clothes. Now, I’m no one’s idea of fashionable, I dress practically and comfortably. This is probably true of most people and has been for as long as we’ve had clothes. High fashion, however, isn’t about being practical or even comfortable, apparently, and the Heian Court is a great example of this.

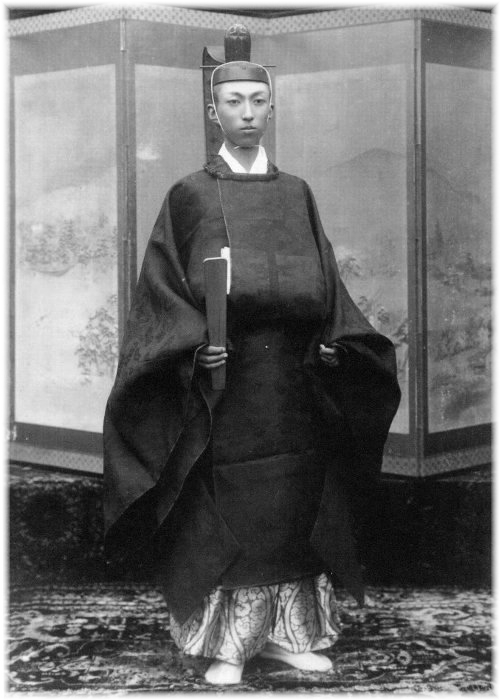

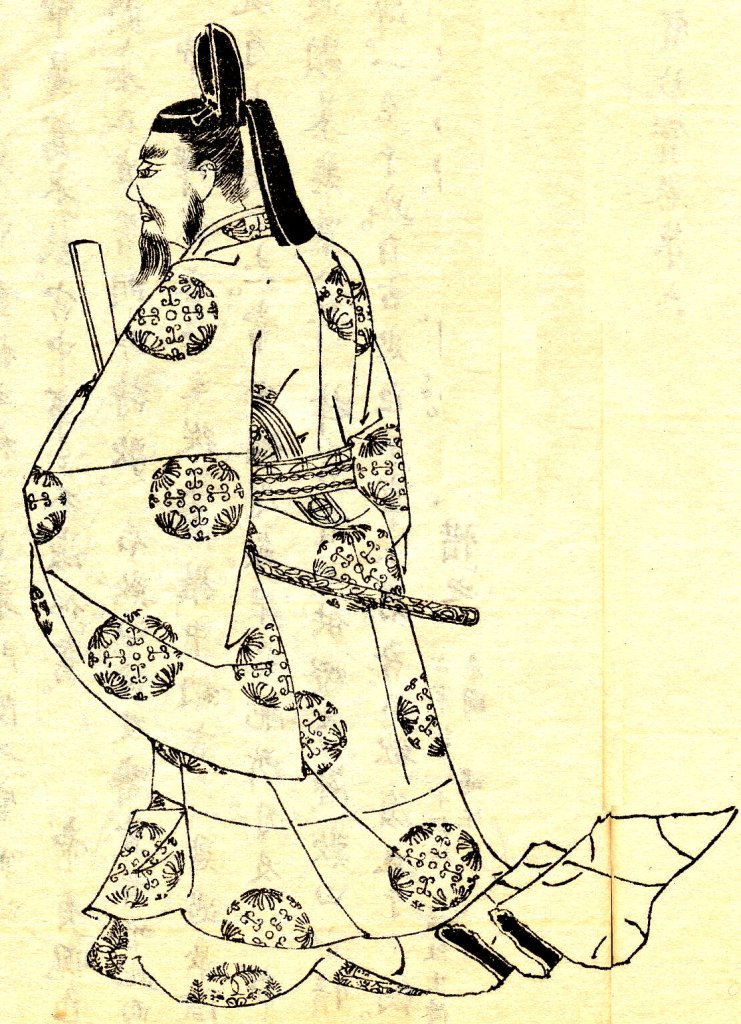

Men and Women were expected to dress differently but with equal flamboyance and impracticality. For men, there were the Sokutai and Ikan, outfits made up of multiple layers that would vary depending on rank, season, and occupation. For example, military officials would dress differently to civilian ones, and versions with fewer layers and shorter sleeves would be worn during the summer months and visa versa.

首相官邸 – https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/gishikitou_iinkai/dai6/siryou1-1.pdf, CC 表示 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=80965200による

Generally, Sokutai was the more formal wear, and Ikan was more of a “work” uniform for courtly officials, although the distinction is not always a clear one, as both sets of clothing were highly elaborate by today’s standards.

Despite its flamboyance, Sokutai is still seen in Japan today. Whilst you’re not likely to catch the average Salaryman wearing it on the morning commute, the Imperial Family still wear it, although usually only at ceremonial functions, like Coronations and Royal Weddings.

By 内閣府ホームページ, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=89645372

Sokutai and Ikan are heavy, impractical clothing options, but that’s kind of the point. Wearing a metric tonne of silk and ornaments is a great way to demonstrate that you’re a world apart from the peasantry who are, by the nature of their lives, required to wear cheaper, more practical and (I suspect) more comfortable clothing.

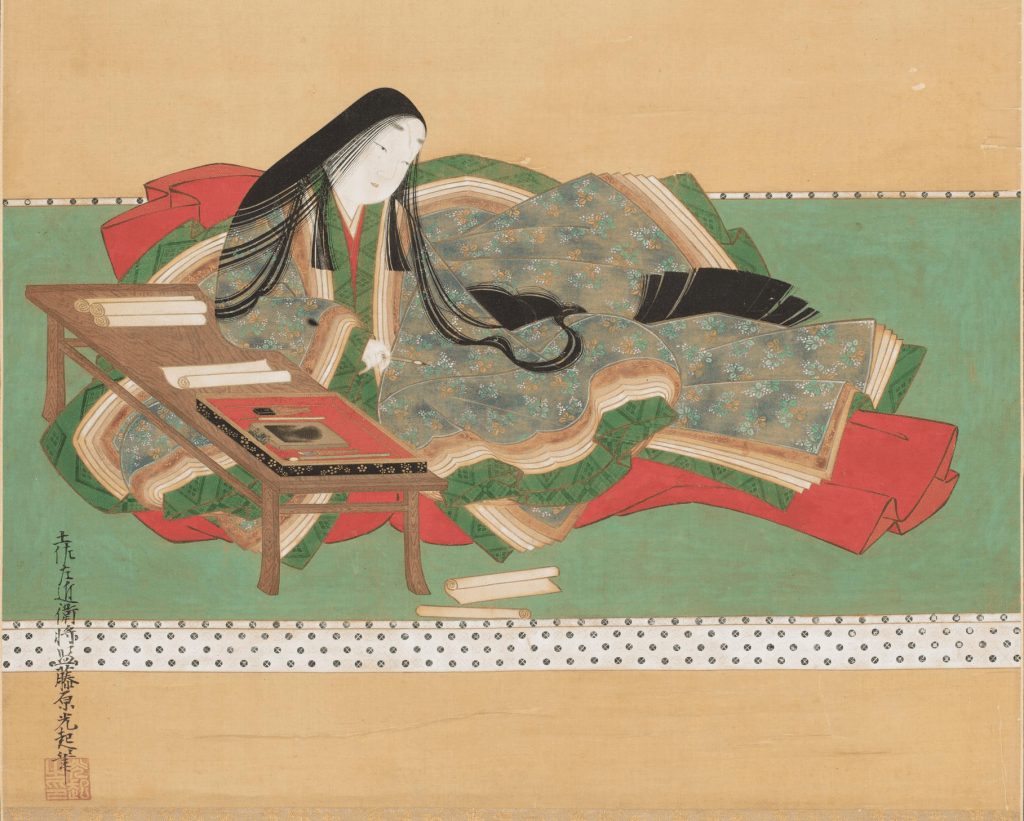

It was worse for women (surprise, surprise). Whilst male clothing was cumbersome, there were certain practical considerations. Men at the court were generally expected to have some kind of job, which limited how impractical their clothing could be. Court Women, however, unburdened by the expectation of actually doing anything, were consequently expected to dress accordingly.

Introducing the Junihitoe, or Twelve-Layer Robe. Yeah, the name isn’t a red herring; while it is true that there may not have been exactly Twelve Layers, the complexity of the Junihitoe was matched only by the need for appropriate colour coordination.

The sheer weight of a Junihitoe ensemble is reflective of attitudes towards women at the time. They weren’t expected to do very much except sit around, being attractive and writing poetry. If you think I’m over-generalising, consider that the full weight of all the robes together could be upwards of 20kgs (44lbs) at a time and place where most people averaged about 5ft tall (152.4cm) and rarely weighed in at heavier than 50 kgs (110lbs). Heian Court Ladies could find themselves wearing half their own body weight in silk and accessories. If you can still manage to look pretty under all that, then you’re a better man than me. Or a better Heian Court Lady, but you get the idea.

If the weight of all that fanciness wasn’t bad enough, fashion dictated that the multiple layers be colour-coordinated according to the season or to other special events. These colours were meant to match the “spirit” of the season, leaning into the Heian Court’s love of symbolism, metaphor, and fancy nonsense.

The layers were supposed to compliment each other, but given the nature of clothing at court, the layers themselves were generally only visible at the sleeves. This might raise the question, why go to all that trouble for multi-coloured sleeves? But when they were done with all that poetry and story writing, what else was there to do but coordinate your sleeves?

It’s all in the eyebrows

So, we’ve already established that Men and Women at the Heian Court were religious, literate, and dressed to impress, but what did they actually look like? More accurately, what did they aspire to look like?

Even today, beauty standards are more about what people think they should look like rather than what they do, and in the era before photographs, most art presented a highly stylised idea of what people actually looked like. (Yes, we still do that with Photoshop, I know.)

Much like the beauty of someone’s handwriting and the sheer weight of silk they could handle, someone’s beauty informed what kind of person they were. Basically, being pretty meant you were a good person, but what did being ‘pretty’ actually mean?

As you can see in the images above, women grew their hair long and typically kept it loose, with dark, shiny hair being preferred. Men, on the other hand, wore their hair up and sported thin moustaches and beards.

Well, both genders seem to have made use of make-up, usually in the form of skin-whitening powders. This is something that’s come up pretty frequently throughout history: paler skin typically suggests that a person doesn’t spend much time outside. In the pre-modern era, a tan meant working outside, which meant you were a commoner, and if there was one thing the people at the Heian Court would not stand for, is was being thought of as common.

In addition to whitening powders, women also painted their mouths to look red and small. They also practised a grooming technique called Hikimayu in which the eyebrows were shaved and then drawn way up the forehead, and it’s quite the look.

If shaved eyebrows aren’t your thing, how about blackened teeth? Don’t worry, they’re not rotting. Actually, some people speculate that the teeth blackening (Ohaguro) actually contributed to healthy teeth by acting as a kind of sealant, so beauty aside, there’s that.

The exact reasons for the start of Ohaguro aren’t clear, but one theory holds that, in combination with the whitening powder, painted mouths, and shaved eyebrows, blackened teeth contributed to a “mask-like” appearance that made it easier to hide emotion.

Heian style fashion would remain in vogue at court for centuries (as seen by traditional dress at Imperial Family events), and this was partly due to the increasing and eventual near total isolation of the Imperial Court in the years that followed the Heian Period.

We’ve discussed how the rot set in previously, but there is one family who might be more to blame than any other, the Fujiwara, who we’ll talk about next time.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J%C5%ABnihitoe

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%89%B2%E7%9B%AE

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%A5%B2%E3%81%AE%E8%89%B2%E7%9B%AE

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hikimayu

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%A1%A3%E5%86%A0

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%AE%BF%E7%9B%B4

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enryaku-ji

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ohaguro