According to historians, the Kamakura Period (named for the eponymous city in modern Kanagawa Prefecture) began in 1185. You probably know by now that history is never that neat. For starters, Minamoto no Yoritomo, the ‘first’ Shogun of this period, wasn’t actually granted the title until 1192.

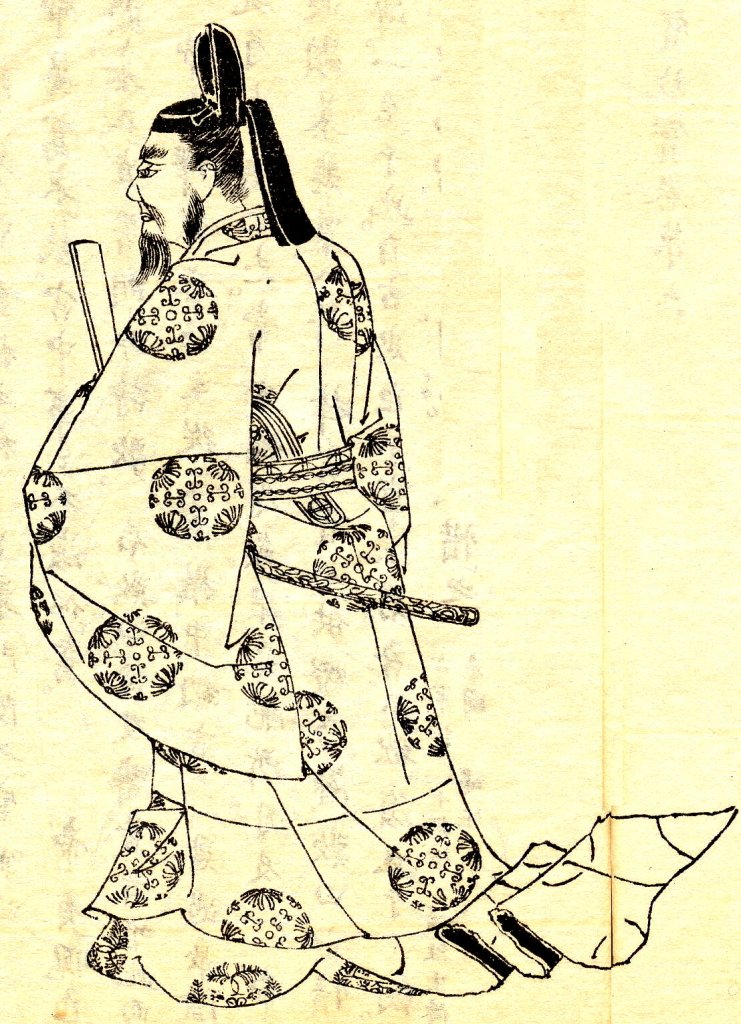

Despite some unclear dates, the reality is that Imperial power had been in decline for centuries. The rising warrior class (Samurai) had had effective control of the provinces for years, and one clan, the Taira, would rise to take effective control of the government, though their leader, Taira no Kiyomori, would not take the title of Shogun and nominally ruled through the Emperor.

Taira control came to an end at the Battle of Dan-no-Ura in 1185, and they were replaced by the Minamoto. We’ve already discussed them, but in summary, the Minamoto, much like the Taira, were a sprawling extended family whose wealth and power did not come from Imperial prestige or titles, but control of the land and the armed men who protected it.

After Dan-no-Ura and the end of the Genpei War, the Minamoto were in control, but here’s where history takes a turn. Previously, clans like the Soga, Fujiwara, and Taira had taken control of the capital, and they exerted influence on the court through political appointments, marriages, and the occasional use of force. The clans would sometimes become powerful enough to reduce Imperial rule to a mere concept, but the illusion of Imperial power was always formally maintained.

The Minamoto were different. Firstly, they didn’t base themselves in the capital, even after their victory over the Taira. The Minamoto base, and centre of their power, was at Kamakura, and that is where they remained. After 1185, Yoritomo would pay lip service to the Emperor, but he began appointing his own provincial administrators, cutting the court out of the process entirely.

In 1189, Yoritomo undertook an invasion of the northern provinces of Dewa and Mutsu. These provinces were ruled by the remnants of the Northern Fujiwara clan and had been largely independent since the outbreak of the Genpei War in 1180. It was also an area that harboured Minamoto rivals to Yoritomo.

Before the outbreak of what would become known as the Oshu War, Yoritomo sought the permission of the Imperial Court to lead the army against the ‘rebels’. This was a formality, but technically the Emperor still had the right to select the General of ‘his’ army.

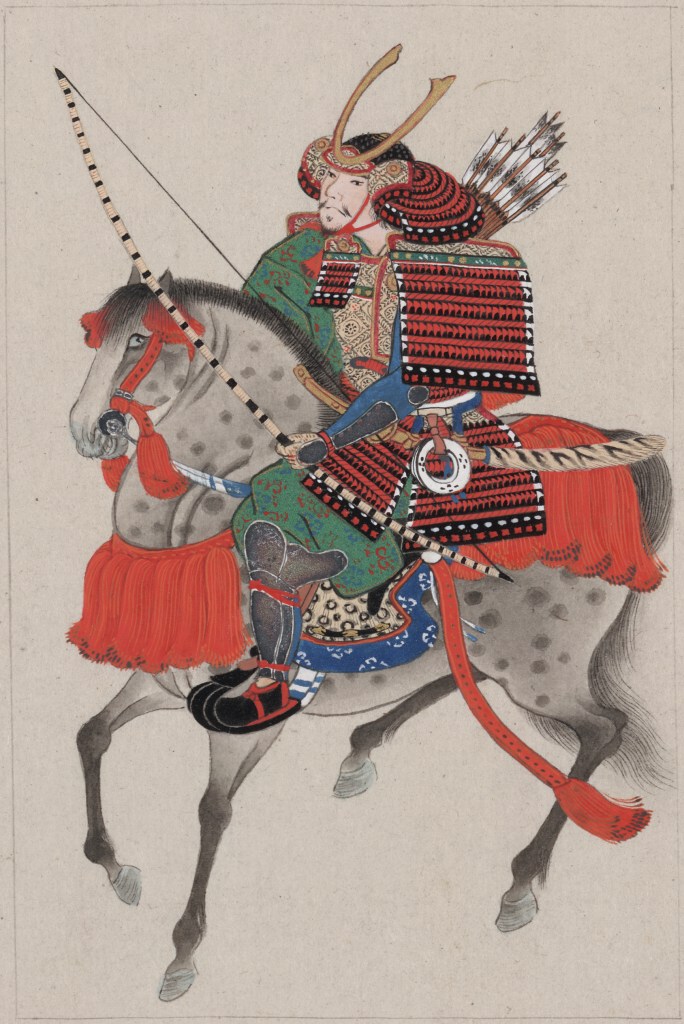

However, Yoritomo didn’t wait for permission to be granted. Instead, he summoned warriors from across Japan, and they answered the call from as far away as Satsuma Province in southern Kyushu (in modern-day Kagoshima Prefecture). Throughout the summer, the Imperial Court made a lot of noise, trying to dissuade warriors from joining Yoritomo, but it did no good. If Japan had been waiting for a sign that power had definitively shifted, then this was it.

The Oshu War lasted around 40 days, and Yoritomo achieved a complete victory. The Court, apparently trying to save face, offered its formal congratulations and a retroactive ‘permission’ for the war. Though the formalities had been observed, no one was fooled; Yoritomo was the boss now.

Yoritomo’s main rival at court was the Emperor Go-Shirakawa, who had abdicated in 1158 and ruled as an insei or cloistered Emperor, influencing events at court for years. Though the two men would cooperate occasionally, especially against the Taira, it wasn’t long before the relationship broke down. Luckily for Yoritomo, and unluckily for Imperial power, Go-Shirakawa died in 1192, and the last real opposition to Minamoto dominance died with him.

It is debated as to whether or not Go-Shirakawa actually sought to prevent Yoritomo from taking the title of Shogun, but the timing is certainly interesting. Go-Shirakawa died in April 1192, and Yoritomo was raised to Shogun in July, giving some credence to the idea that the only obstacle had been the Emperor.

The title of Shogun, more appropriately, Seii taishōgun, is literally translated as Commander-in-Chief of the Expeditionary Force Against the Barbarians (which is a bit of a mouthful, I agree), and had always been a temporary title before. In the Yamato Period and early Heian, the Emperor would issue a ceremonial sword to a General before sending him against the Empire’s enemies (usually the Emishi Tribes in what is now northern Japan).

The title seems to have fallen out of use in the 10th century as the Emishi had ceased to be a threat, and there was no longer any need for a Supreme Commander. Yoritomo’s assumption of the title reflected the new reality. His was not a government that was based on divine origins, or the glitz and glamour of Imperial ceremony. He had taken power through military strength, and he would rule Japan in the same way.

Though Yoritomo was obviously a capable commander and administrator, he also took advantage of powerful alliances in and around his home provinces. His marriage to Hojo Masako (an important figure in her own right) brought him the support of the powerful Hojo Clan, who would go on to play an important role in the Kamakura Government.

The strength (and, ironically, the eventually fatal weakness) of the Kamakura government was its decentralisation. Japan had been divided into provinces during the Taika Reforms over 500 years earlier, with each province being further divided into districts.

The system had relied on officials appointed by the Imperial Court to run it, and when Yoritomo took over, he replaced Imperial Officials with Gokenin. This new system was pretty much the same as the one it had replaced, with officials appointed by the Shogun to oversee lands that they didn’t own.

The power of the Shogun came from the exclusive right to appoint these officials, but over time, they become de-facto hereditary, meaning that later Kamakura-based Shoguns would face exactly the same problem as the Emperors had, nominal vassals who were in reality heavily militarised, semi-independent principalities, who were not interested in obeying the government.

The Great Hunt

All that was in the future, and Yoritomo was focused on establishing the power of his regime in the short term. In the summer of 1193, Yoritomo called all his retainers to a great hunt in Suruga Province, not far from his capital. The so-called ‘Fuji no Makigari” (Hunt near Mt Fuji) was apparently attended by upwards of 700,000. Though that does seem implausibly high (and probably is), it does go some way to showing how high-profile an event this was. There were also a few incidents that highlight the complexities of power, both within the family and outside it.

Firstly, when Yoritomo’s son and heir, Yoriie, killed his first deer, Yoritomo stopped the hunt to call for a celebration. Now, I don’t know if you’ve ever tried to shoot anything with a bow, let alone a deer, but it’s not easy, and Yoriie was only 12, so good for him, right?

Well, it turns out, not so much, when Yoritomo sent a message to his wife, and the boy’s mother, Hojo Masako, inviting her to the celebration, she sent a message back stating that the son of a Shogun being able to shoot a deer was no reason to celebrate.

Hojo Masako, the original Tiger Mum.

Another incident, which wasn’t political exactly, but still a bit weird, was when Kudo Kagemitsu, a famous archer, shot at a deer and missed three times. He would claim to be baffled, and that the deer must have been the one that the Gods of the mountains rode. Which I’m sure it was. It’s a convenient excuse anyway. Kagemitsu would apparently get sick and collapse that very evening, and Yoritomo even considered calling off the hunt, but he didn’t, and they carried on for another week, so there’s that.

The third incident is certainly the most serious, and has a name that probably explains itself: The Revenge of the Soga Brothers.

These Soga aren’t the same as the Soga who had first dominated the Imperial Court in the Yamato Period; instead, they were a clan based in Sagami Province (most of modern-day Kanagawa) near Odawara. The target of the Soga’s vengeance was Kudo Suketsune, who had accidentally killed their father in a dispute over land, or a woman, or something. It’s complicated, but Samurai love a vendetta, and even though Suketsune’s death had been an accident, the Soga Bros, Sukenari and Tokimune, swore revenge.

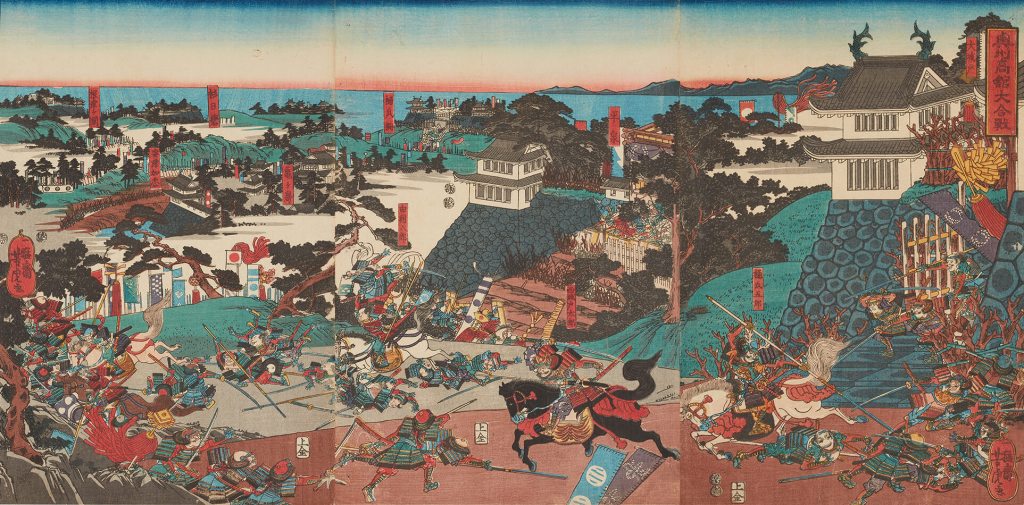

Now, the exact details of the attack are recorded in the Soga Monogatari, which is of unknown authorship, and tends to sensationalise quite a lot of what happened, and the Azuma Kagami, which is heavily biased towards the Kamakura government. Both sources share some similarities and some differences, but the basic outline is that the brothers attacked and killed Suketsune either at an inn or in a mansion, where he was attended by one or possibly two prostitutes.

The sources agree that the brothers killed Suketsune with their swords, but the Soga Monogatari says they also killed one of the prostitutes, or maybe just cut her legs off, which I guess was fine?

Both sources agree that the brothers attacked and killed many warriors, with the Azuma Kagami suggesting that this was part of an attack on the Shogun, whilst the Monogatari says it was all about killing as many enemies as possible, to make their mark on history.

Both sources also agree that Sukenari, the elder brother, was cut down in the melee, but Tokimune was captured, and subject to interrogation, before being put to death.

This story was romanticised as heck later on, especially during the Edo Period, and why not? After all, what’s more inspiring than a story about a pair of brothers who avenge their murdered father before going on to slaughter a bunch of people who had nothing to do with it?

Whether or not the Soga Brothers actually attempted to kill the Shogun, this episode highlights the often chaotic and bloody reality of a government run by warriors.

Yoritomo would become a monk, and then almost immediately die in February 1199, leaving his son Yoriie as the second Shogun. Yoriie would immediately come under the influence of his grandfather, Hojo Tokimasa, and mother, the aforementioned Hojo Masako. Pretty soon, the same problems that had plagued the Imperial Court began affecting the Shogun’s court too, but more on that next time.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kamakura_shogunate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_%C5%8Csh%C5%AB

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minamoto_no_Yoritomo

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%BA%90%E9%A0%BC%E6%9C%9D

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shogun

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emperor_Go-Shirakawa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H%C5%8Dj%C5%8D_Masako

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gokenin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fuji_no_Makigari

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revenge_of_the_Soga_Brothers

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Azuma_Kagami

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soga_Monogatari