Having looked closely at the lives and careers of Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin, it is impossible not to notice the frequent mention of a place called Kawanakajima, and the series of battles that took place there from 1553 to 1564.

The battles at Kawanakajima were not the only confrontations between the Takeda and Uesugi clans, nor were they the largest or most significant battles in the Sengoku period, but they have been the subject of extensive study, writing, and mythologising, as they seem to symbolise the famous rivalry between Shingen and Kenshin, and so they’re worth a closer look.

Kawanakajima

By Bloglider at Japanese Wikipedia – Own work by the original uploader (Original text: Photo by Bloglider.), CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12400636

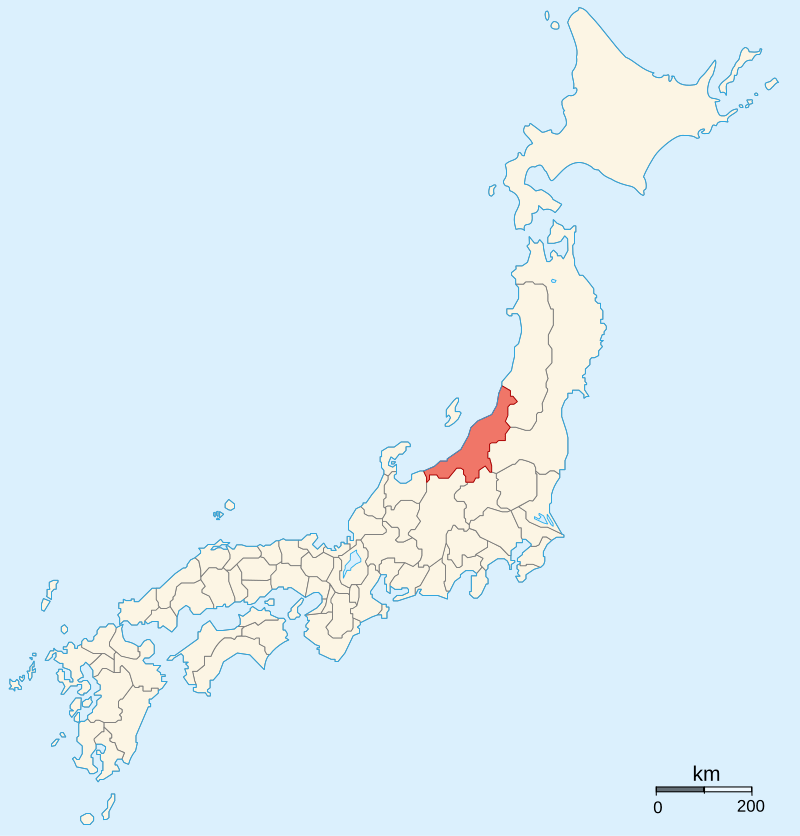

The area called Kawanakajima is located in the northern part of Nagano Prefecture, and is the area surrounding where the Chikuma and Sai rivers meet. Now within the modern city of Nagano, in the 16th century the area was in Shinano Province and had long served as a key transportation route from north to south, and as such had frequently been a battleground.

There had been many small, but long-established clans in the area, but by the early 1500s, it was largely under the control of the Murakami Clan, who would come into frequent conflict with the Takeda, from neighbouring Kai Province, who were beginning to expand into Shinano around this time.

Starting in 1542, Takeda Shingen began a concerted effort to bring the province under his control, but he faced resistance of varying degrees of severity during his campaign, and it was the Murakami who proved the sternest test. At the Battle of Uedahara in 1548, the Murakami inflicted a serious defeat on the Takeda, and although Shingen would recover, he suffered a further defeat at the Siege of Toishi Castle in 1550.

Shingen had what we might call “Bouncebackability”, and in 1551, Toishi Castle fell, leaving the Takeda in control of most of Shinano, with the exception of the area including, and to the north of, Kawanakajima. The clans in this area had previously allied with the Murakami, but with their defeat, they went looking for new friends.

They found them in the Nagao Clan of Echigo, and their lord, Kagetora, better known to history as Uesugi Kenshin, who advanced into northern Shinano to support these local clans and to oppose the Takeda.

The First Battle

In April 1553, Shingen resumed his advance against the remaining clans in northern Shinano, meeting only sporadic resistance and forcing the weakened Murakami to ask for intervention from Kenshin. He responded, and a combined force of around 5000 men counterattacked and defeated the Takeda at the Battle of Yahata in May.

This success would be short-lived, however, as Shingen would resume his advance that summer, forcing the Murakami back again, until September, when Kenshin himself led a force into Shinano, engaging and defeating the Takeda at the Battle of Fuse, before laying siege to several castles in quick succession. Shingen would seek to outmanoeuvre Kenshin and cut off his retreat, but Kenshin responded with a strategic retreat to a place called Hachimanbara.

Unable to cut off Kenshin’s retreat, Shingen instead retreated to Shioda Castle, entrenching himself there and avoiding direct battle. With neither side apparently up for the fight, both armies gradually disengaged, with Kenshin returning home at the end of September, and Shingen following suit a few weeks later.

The First Battle of Kawanakajima was more of an extended series of engagements than a pitched battle, and both sides achieved some strategic goals. Kenshin was able to stop the Takeda advance into northern Shinano, whereas Shingen was able to consolidate his control in the central and eastern parts of the province, free from outside intervention.

The Second Battle

Through the remainder of 1553 and into 1554, Takeda Shingen continued to expand and consolidate his control of the areas of Shinano south of Kawanakajima. He has also formed an alliance with the Hojo and Imagawa Clans, securing his southern borders and gaining an ally (in the Hojo) against Kenshin’s ambitions in the wider region.

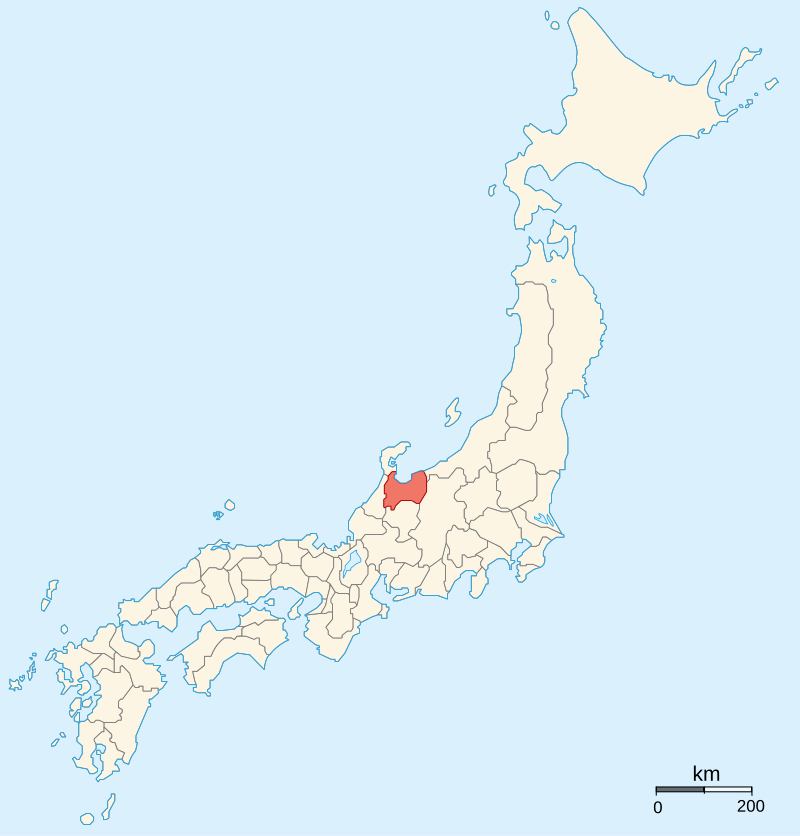

Shingen also sought to keep Kenshin off balance by supporting local rivals and instigating rebellions amongst his vassals. Though Kenshin was often able to swiftly put down these uprisings, in 1555, a previously loyal vassal, Kurita Eiju, who was based near the Zenkoji Temple, defected to the Takeda side. This was significant because Eiju controlled the southern half of the Nagano Basin, of which Kawanakajima was a central part.

By 663highland, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=48785737

Shingen marched north to support his new ally, whilst Kenshin was obliged to dispatch an army to retake the lost territory. Eiju, alongside 3000 Takeda allies, holed up at Asahiyama Castle (in modern Nagano City), a strategically important location that controlled crossings of the Sai River.

Kenshin could have manoeuvred around the strong point, but this would have left an enemy garrison at his rear, so instead, he entrenched his forces at Katsurayama (also in modern Nagano) and constructed a castle there, effectively bottling up the garrison at Asahiyama and neutralising the threat.

Shingen was not idle during all this construction; however, he dispatched an army in support of Kurita Eiju, and it arrived in early July, facing Kenshin’s forces across the Sai River. The only serious engagement of the Second ‘Battle’ was on July 19th, when Kenshin sent forces across the river and engaged in sporadic fighting against the Takeda. Whether this was a serious attempt to force a crossing or just a kind of skirmish isn’t clear, but Kenshin’s forces swiftly withdrew, and both sides spent the next 200 days glaring at each other across the river.

Eventually, events away from Kawanakajima would force a resolution. Shingen was a long way from his home base in Kai and was beginning to struggle to feed his army, whereas Kenshin was facing issues on his western borders from increasing activity from the local Ikko-Ikki, as well as dissatisfaction from his vassals over the months of inactivity.

Eventually, both sides agreed to mediation, led by the Imagawa Clan, and a peace was agreed in October. The terms set the border between the rivals as the Sai River, as well as calling for the destruction of Asahiyama Castle, and the complete withdrawal of both armies from the area.

In the immediate aftermath, Kenshin would turn to deal with the Ikko-Ikki, and Shingen would subdue the remaining independent lords in southern Shinano, but neither side was done with Kawanakajima.

The Third Battle

In 1556, Kenshin, apparently suffering from what we might now call ‘burnout’, announced his intention to renounce his lordship and become a monk. His retainers, horrified at the prospect, did everything they could to persuade him to change his mind. They were ultimately successful, and a good thing too, because through the interim period, Shingen had again begun putting pressure on local lords to switch sides, or face conquest.

During the New Year festivities in January 1557, Kenshin, who had by now given up on his idea of becoming a monk (and the restful lifestyle that would have provided him), offered prayers at the Hachimangu Shrine (in Chikuma, Nagano) for the defeat of Takeda Shingen.

Shingen, apparently put out by these attempts at divine intervention, advanced again, taking Katsurayama Castle (the site of the second ‘battle’) in mid-February, then advanced north, defeating the Takanashi Clan, who were allies of Kenshin. Kenshin’s response was delayed by winter snows, but he eventually came south, capturing several Takeda castles and even rebuilding Asahiyama.

Shingen would continue to evade Kenshin’s advance, and both sides continued to dance around each other until an indecisive clash at Uenohara in late August, after which, Kenshin, who had advanced far from his supply bases in Echigo, withdrew. At this point, the Shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiteru, intervened, sending a letter requesting that both sides make peace, apparently in the hope that they would then send forces to aid the Shogunate.

Neither side did, but a truce was agreed upon, which did not last long, as both Kenshin and Shingen would dispatch armies to duke it out in Northern Shinano. Kenshin arguably got the better of it, as the remaining clans in the area, previously just allies, were forced to become effectively his vassals.

The Fourth Battle

In 1559, Kenshin went to Kyoto to ask that the Shogun grant him the position of Kanto Kanrei, which had long been held by the Uesugi clan. Though the power of the Shogun and the prestige of any positions he might bestow were long since diminished, Kenshin was able to combine his appointment as Kanrei with his considerable martial talents to gather a large army and attack the Hojo in the Kanto region.

In 1560, he was apparently able to gather an army of 100,000 men (though this is probably exaggerated) and advance deep into Hojo territory, even besieging their capital at Odawara in March 1561, though he was unable to take the formidable fortress. In response, the Hojo called for help from their ally, Takeda Shingen, who responded by invading Northern Shinano once again.

By Akonnchiroll – Own work, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=145493350

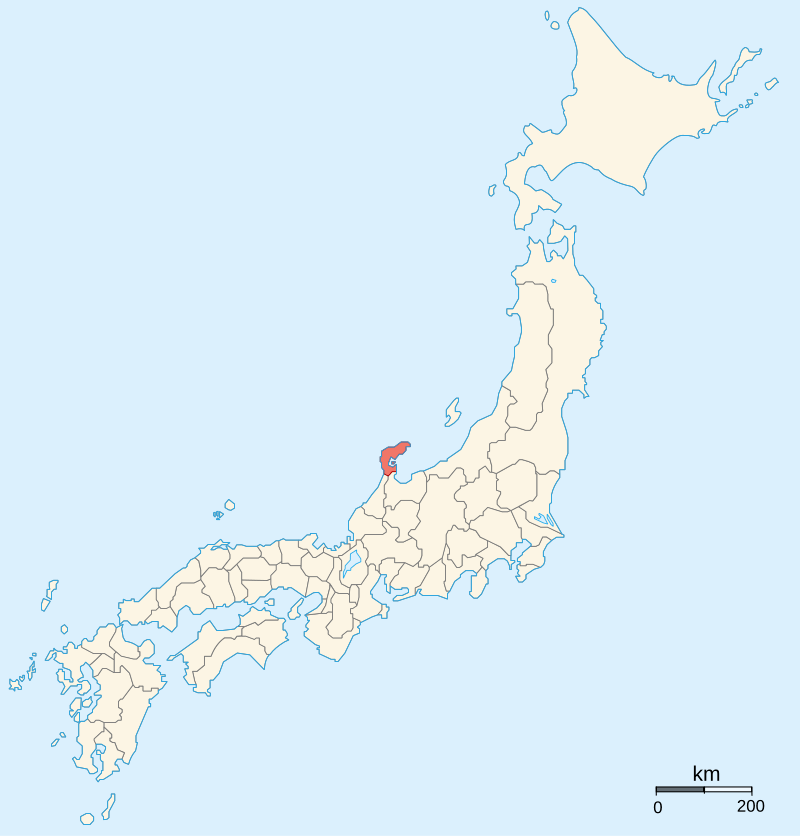

When news of Shingen’s attack reached Kenshin’s army, many of his supporters returned home, and he was obliged to lift the siege of Odawara and turn to face the Takeda. Beginning in August, the Takeda and Uesugi forces would again seek to gain advantage, advancing and retreating in turn, largely centred on Kaizu Castle, newly constructed at Shingen’s command.

This would continue until late October, when the Takeda devised a strategy to launch a surprise attack against the Uesugi, with a second force positioned nearby to ambush and (hopefully) destroy the Uesugi as they attempted to regroup. Kenshin, however, was made aware of the Takeda’s movements, and, taking advantage of a moonless night, he had his army change position, moving them closer to the main Takeda force.

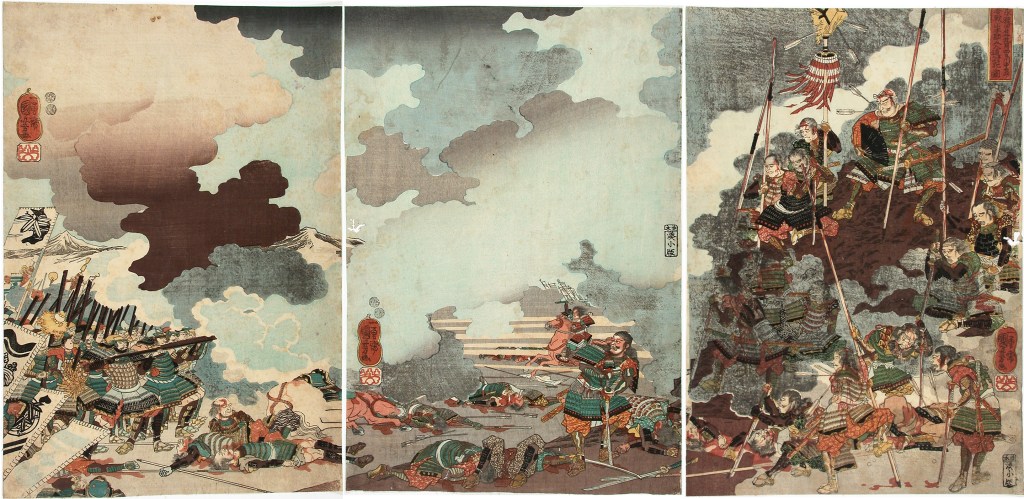

Just after dawn on October 28th, a thick fog covered the ground around Kawanakajima, obscuring both armies. When the fog cleared, however, the Takeda were confronted with the sight of the entire Uesugi army positioned in front of them. Almost as soon as visibility allowed, Kenshin ordered a furious attack that smashed into the Takeda force and forced them onto the back foot.

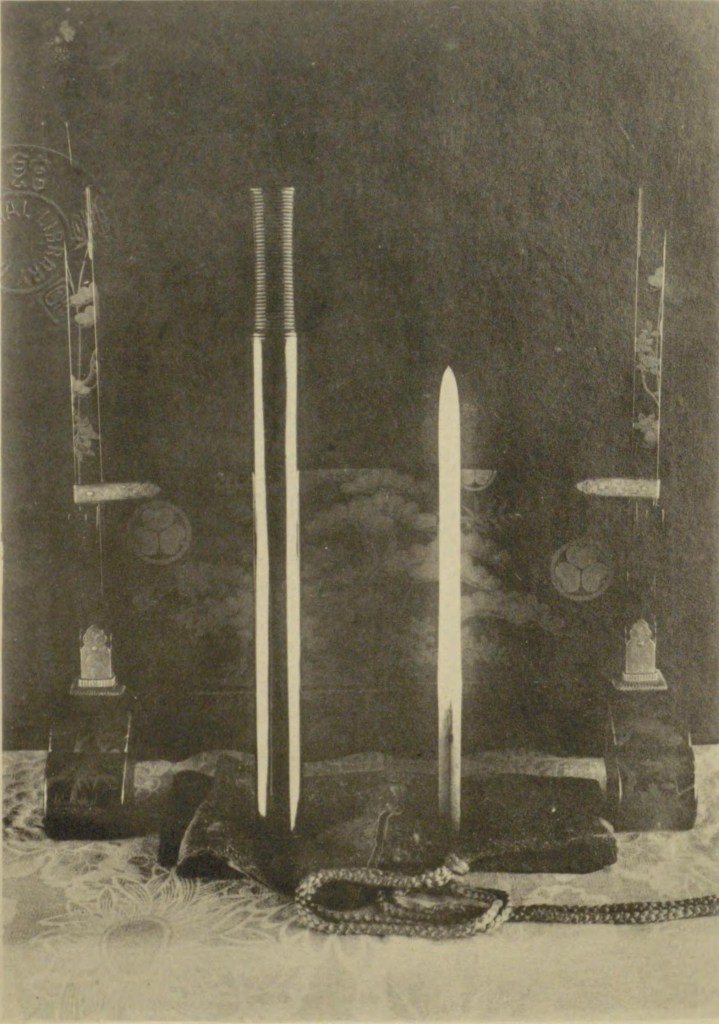

The Uesugi made it as far as the Takeda’s main camp, and it is here that one of the most famous tales of the Sengoku period takes place. In the heat of the battle, a warrior wearing a white robe (or towel) around his head charged directly at Takeda Shingen. This warrior slashed three times at Shingen, who was able to parry the blows with his war fan (made of iron, not the usual paper, luckily), before Takeda’s soldiers came to the rescue and forced the white-clad warrior to retreat.

It was later revealed that this warrior was Uesugi Kenshin himself, and the duel became a legendary scene, symbolising the violence of the age, and the particular rivalry between Shingen and Kenshin. Unfortunately, we’re not sure that the duel actually took place. Takeda sources describe it as I’ve written here, whereas the Uesugi say the duel did take place, but that it was either a different attacker, or that it took place, not in the Takeda camp, but nearer the river, where the fighting was fiercest.

Whether the famous duel actually happened or not, the battle itself was a bloody affair. The Uesugi attack was ferocious and drove the Takeda back to their camp, but failed to break them. At the same time, Takeda reinforcements rushing towards the battlefield were held up by a Uesugi rearguard.

If the battle had been brought to a conclusion that morning, then it’s likely the Uesugi would have won; however, the Takeda reinforcements arrived at around noon, and, fearing encirclement, Kenshin ordered a retreat. Shingen pursued him until around mid-afternoon, but then called it off, bringing an end to the bloodiest of the Battles of Kawanakajima.

Exact death tolls are always tricky, as are the size of the opposing armies, but total numbers of combatants are estimated to have been around 20,000 for the Takeda and 13,000 for the Uesugi. When the fighting was over, the Takeda had suffered 4000 casualties, to the Uesugi’s 3000, and since they remained in control of the field, the battle was arguably a Takeda victory.

That being said, the Uesugi would also claim victory, as they had foiled Takeda’s attempts to trap them, stopped their advance, and, despite a bloody day, their army remained more or less intact. Strategically, the battle was probably a draw, as it ultimately didn’t change much on the ground, neither side was able to secure new territory in the aftermath, and apart from the casualties (who would no doubt be comforted to know they’d died for nothing), both sides remained relatively strong.

The Fifth Battle

The Fifth and Final Battle of Kawanakajima occurred in 1564. In the interim period, Kenshin had continued to send forces into the Kanto, and Shingen had continued to try to expand his control of Shinano and other surrounding provinces.

In Hida Province, a proxy war between a faction backed by the Uesugi and one by the Takeda swiftly drew both clans into direct confrontation once again. Shingen dispatched troops, and Kenshin moved to intercept them. The Takeda would get as far as the southern end of the Nagano Basin, but there would be no serious fighting. The Uesugi were content to limit themselves to blocking Shingen, and Shingen seemed to be content to allow himself to be blocked.

Both sides eventually withdrew after nearly two months of little more than dirty looks, and this would prove to be the last confrontation between the clans at Kawanakajima.

Aftermath

The conflict between the Takeda and Uesugi Clans did not end after the Fifth Battle (such as it was), but both sides had more pressing concerns elsewhere. Kenshin was keen to focus on Etchu Province, the source of frequent Ikko-Ikki attacks, whilst Shingen’s attention was drawn south, and then eventually towards Kyoto as the political situation shifted dramatically.

When Shingen died in 1573, Kenshin is supposed to have wept openly at the loss of his great rival, but the fortunes of both clans would continue to decline. The Takeda would be heavily defeated at the Battle of Nagashino in 1575, and their power would be permanently diminished. Then, in 1578, Kenshin died, and the Uesugi Clan was wracked by a civil war to determine who would succeed him.

The Takeda would eventually be destroyed by Oda Nobunaga in 1582, whereas the Uesugi would survive the Sengoku Period and the centuries to come. In fact, as I mentioned in their brief profile, direct descendants of this famous clan still live in Japan to this day.

Ultimately, the Battles of Kawanakajima became the stuff of myth and legend in the decades following the actual events. This was largely due to the actions of Tokugawa Ieyasu and his descendants, who made concerted efforts to elevate the actions of Takeda Shingen to almost semi-divine status.

The reality is that the battles were locally important, but ultimately proved to be fringe events in the course of the enormous bloodshed elsewhere in Japan during this period, as we shall soon see.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BF%A1%E6%BF%83%E6%9D%91%E4%B8%8A%E6%B0%8F

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battles_of_Kawanakajima

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B7%9D%E4%B8%AD%E5%B3%B6%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%97%AD%E5%B1%B1%E5%9F%8E

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AD%A6%E6%B0%B4%E5%88%A5%E7%A5%9E%E7%A4%BE

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%AB%98%E6%A2%A8%E6%B0%8F%E9%A4%A8

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uesugi_Kenshin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Takeda_Shingen