At the end of the last post, we covered an outbreak of rebellion led by the Uesugi Clan in the Kanto Region. This rebellion was put down, and the Uesugi were badly mauled, but the consequences of it would be long-reaching indeed.

We haven’t spent a lot of time talking about the Kanto recently; most of the events of the preceding Nanbokucho Period happened in and around Kyoto, so this seems like a good opportunity to update you on what was happening in the area, which is now mostly modern Tokyo and its surroundings.

You may remember that the government, prior to the Ashikaga Shogunate, had been the Kamakura Shogunate, based in the town of the same name. Kamakura itself is in the Kanto and was, at the time, a major population centre.

When the Kamakura Shogunate was overthrown, the Ashikaga based themselves in Kyoto, but didn’t lose sight of their position in the Kanto. With power in Kyoto confirmed, the first Ashikaga Shogun, Takauji, sent his second son to Kamakura to oversee things there.

The position of Kamakura Kubo was initially a solely military post, with the mission being to keep order in the provinces. However, within a few decades, it had transformed into a political and administrative position as well, with the kubo being the effective governor of a large area of eastern Japan.

Pqks758 – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30770440による

The other major power in the region was the Kanto Kanrei, the Shogunate Deputy in the Kanto region. Originally an administrative position, subject to appointment and dismissal by the Shogun, by the late 14th Century, the position had become the hereditary title of the Uesugi Clan, who used it to become the dominant power in the region.

Officially, the Kubo was a military position, whilst Kanrei was an administrative one, but the reality was that there was considerable overlap between both positions. The Kanrei was supposed to be subordinate to the Kubo, but the situation on the ground meant that the Kanrei often controlled more land and men than the Kubo.

There were several clashes between both positions, and the government in Kyoto, but one of the most serious was the Uesugi Rebellion in 1416, which we talked about last time. Although the rebellion was crushed, the situation in the Kanto remained tense in the aftermath.

Firstly, the Kubo at the time was Ashikaga Mochiuji, who had an unfortunate habit of ignoring instructions from Kyoto that didn’t suit him. In the aftermath of the rebellion, the Shogun, Yoshimochi, had wanted to pursue a policy of reconciliation, similar to that of his father.

Mochiuji, however, wanted revenge; he saw the powerful clans in the Kanto as a direct threat to his rule and was determined to crush them once and for all. He began taking direct action against families that had joined the rebellion, and despite issuing orders for him to stop, the government in Kyoto proved powerless to curb his violent tendencies.

Yoshimochi wasn’t idle, however. Although the position of Kamakura Kubo was a powerful one, and Mochiuji had many supporters, there were others who remained opposed to him. Yoshimochi took advantage of this, extending direct vassalage to several important families in the Kanto region and elsewhere. Though these families technically owed allegiance to Kamakura, they were now direct vassals of the Shogun.

Though this policy may have seemed like a good idea at the time, it would backfire. In 1422, the Oguri Clan, with the implied support of the Shogun, rose in rebellion against Kamakura and Mochiuji. Whether or not the Oguri expected support from Kyoto, it didn’t come, and Mochiuji personally led the army that put the rebels down.

In response, the Shogun gave serious consideration to military action, but it was eventually decided to do nothing but demand a formal apology from Mochiuji, which he quickly agreed to, bringing an end to the immediate crisis.

Things jump ahead a little bit here. In 1423, Shogun Yoshimochi retired and officially handed over the title (but not the power) of Shogun to his son, Yoshikazu. This arrangement didn’t last long; Yoshikazu died within two years (apparently from alcohol-related issues).

The position of Shogun was then left vacant, but since Yoshimochi held the actual power, the government kept going regardless. This changed in 1428, when Yoshimochi himself died, seriously impeding his ability to run the state.

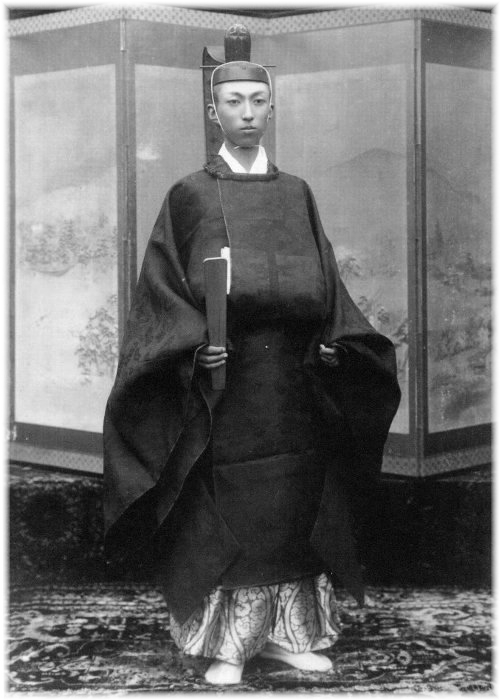

Yoshimochi had no more sons, so a new Shogun was sought from amongst his brothers. Apparently, they did this by a lottery, and the name drawn was Yoshinori. The problem with that was that Yoshinori (who was also called Yoshinobu for a time) had become a monk during his youth.

There was plenty of precedent for important officials to retire and become monks, but there was none for it happening the other way. At first, the selection of Yoshinori was opposed; he was a monk, for starters, and there were rumours that Mochiuji, the Kamakura Kubo, would be declared Shogun instead.

Several tense months followed, including the death of one Emperor and the accession of another. It was this new Emperor, Go-Hanazono, who would name Yoshinori Shogun in March 1429. Yoshinori seems to have tried to model himself on his father, the great Yoshimitsu. He attempted to centralise power in Kyoto and curb the influence of powerful local deputies (Kanrei), and he even restarted the trade with China.

However, Yoshinori was not Yoshimitsu, and the situation for the Shogunate was not as it had been 30 years earlier. Yoshinori would have some success initially, bringing restive lords in Kyushu back in line, and moving to end the Shogun’s reliance on the military strength of the Shugo (governors) as his predecessors had been forced to.

Trouble was never very far away, however, and in 1433, ongoing conflicts between rival temples in and around Kyoto flared up again. Now, Yoshinori had been a monk of the Tendai Sect, specifically at the Shoren-in Temple.

Now, the intricacies of temple politics in this era are complex to say the least, but the short version is that there were various sects of Buddhism prominent in Japan at this time. These sects were then often further subdivided, and, in keeping with the style of the time, these factions would often engage in vicious and sometimes violent rivalries with each other.

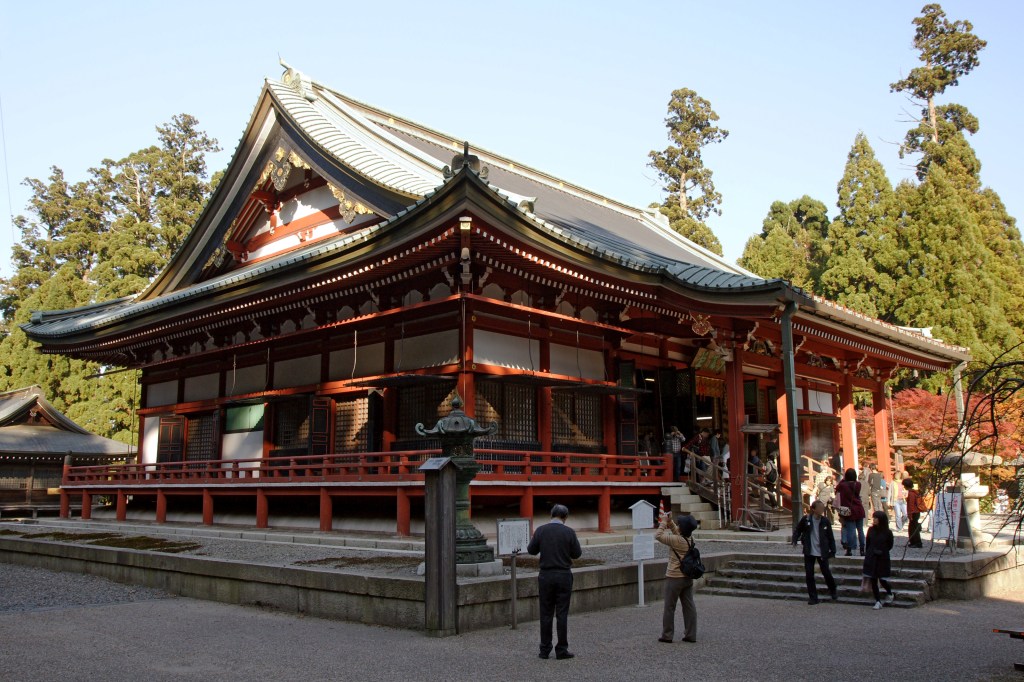

At this time, one of the most violent disputes was between the Jimon (Temple Gate) and Sanmon (Mountain Gate) branches of the Enryaku-ji Temple on Mt Hiei, near Kyoto. Yes, you read that right, they were rivals from the same temple complex.

663highland, CC 表示 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8449808による

In July 1433, the monks of the Sanmon Faction submitted a petition of 12 complaints to the Shogun, making allegations of misconduct against the Shogunate officials in charge of religious affairs.

The Shogun took a conciliatory approach to this, accepted the petition and then apparently dismissed the officials in question. The Sanmon Monks, apparently getting a bit full of themselves, celebrated by burning down Onjo-ji (sometimes known as Mii-Dera), the headquarters of the Jimon Faction.

Now, the Shogun was understandably annoyed by this. Apparently, the monks of Onjo-ji had refused to join the Sanmon Faction’s petition, but that wasn’t a good enough excuse, and Yoshinori dispatched troops to Mt Hiei, demanding that the monks of Enryaku-ji surrender.

This they did, but the peace didn’t last long. Within a few months, rumours began spreading that the Monks were conspiring with Ashikaga Mochiuji, apparently trying to curse the Shogun, and general praying for his downfall, which in a superstitious age was a big deal.

In response, the Shogun confiscated property belonging to the temple and sent troops to surround the temple, effectively putting Enryaku-ji under siege. From July to December 1434, no one could get in or out of Mt Hiei, and the monks were eventually compelled to seek terms of surrender.

Shogun Yoshinori was in a far less forgiving mood this time, and he was initially reluctant to accept terms. However, under pressure from his own government, he accepted the surrender, and the previously confiscated property was returned.

This was apparently just a ruse, however, and in February 1435, Yoshinori had four Enryaku-ji monks arrested and beheaded. The monks on Mt Hiei were outraged by this and set fire to their own temple, with 24 of them meeting their ends (more or less willingly) in the flames.

Mt Hiei is easily visible from Kyoto, and the sight of the temple in flames caused outrage in the city. Yoshinori responded by issuing an edict sentencing anyone who complained about the situation to death, which apparently worked wonders in keeping the population quiet.

With the Sanmon Faction subjugated, Yoshinori then turned his eyes back to the Kanto. All he needed was a pretext, and luckily for him, one would not be long in coming.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%8E%8C%E5%80%89%E5%BA%9C

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E6%8C%81%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%96%A2%E6%9D%B1%E7%AE%A1%E9%A0%98

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%8A%E6%9D%89%E7%A6%85%E7%A7%80%E3%81%AE%E4%B9%B1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashikaga_Yoshikazu

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E9%87%8F

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashikaga_Yoshinori

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%BB%B6%E6%9A%A6%E5%AF%BA

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jimon_and_Sanmon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mii-dera

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E6%95%99#%E6%AF%94%E5%8F%A1%E5%B1%B1%E3%81%A8%E3%81%AE%E6%8A%97%E4%BA%89

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B0%8F%E6%A0%97%E6%BA%80%E9%87%8D%E3%81%AE%E4%B9%B1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BA%AC%E9%83%BD%E6%89%B6%E6%8C%81%E8%A1%86