Last time, we talked at length about the Fujiwara family. We looked at how they rose to power and came to dominate the Imperial Court through a combination of violence, intrigue, and incestuous marriages.

The Minamoto were far from the only noble family, however. Although there were literally dozens of families, cadet branches and noble upstarts, by the beginning of the Heian Era, there were four main houses: the Fujiwara, Taira, Minamoto, and Tachibana families.

We’ve already talked at length about the Fujiwara and their origins, but what about the other three? First, a bit of background: Emperors generally had more than one consort, though there was technically only supposed to be one “Empress” This was routinely flouted during the Heian Period, especially by the Fujiwara, and besides official wives, the Emperor would take other noble women as concubines.

In the days before family planning, this meant that any Emperor could have far more children than he knew what to do with. This would frequently lead to instability at court, as rival factions would form around different heirs, but what about the sons who were born to lower ranked women, or otherwise lacked legitimacy and support?

Well, that’s where the Taira, Minamoto, and Tachibana come in. Technically, these three families didn’t start out as families at all; instead, the names were bestowed on these “extra” Imperial princes, who were excluded from the throne and would then go off and start houses of their own as part of the nobility.

The Tachibana were the first (708), followed by the Minamoto (814) and the Taira (825), but things get complicated almost immediately. The problem is that one Emperor might bestow the name Minamoto on his grandson, only for another Emperor a generation later to do the same thing, creating two families that share a name.

Whilst this isn’t uncommon in the modern world (How many Smiths do you know?), it does make it tricky to keep track of who is who when writing up a history blog. For the purposes of keeping things concise, I will be referring to all branches of each clan by the same name unless it’s important to make a distinction.

It’s honestly not that bad with the Tachibana, as there were only two main branches. Even the Taira only had four, but the Minamoto had twenty-one, and that’s where it gets silly. It’s even worse when you realise that most, if not all, the later Samurai houses claim descent from at least one of the four major Heian Families, but we’ll get to that later.

Tachibana

We’ll start, as they say, at the beginning. Though the Fujiwara would emerge in 668, fifty years before the Tachibana, the latter family are the first of these Imperial “offshoots.” (The Fujiwara were pre-eminent but were not founded by the son of an Emperor).

The Tachibana initially came into being in 708, when court Lady Agatainukai no Michiyo was given the honorary name “Tachibana” by Empress Genmei. The clan’s name was officially changed to Tachibana in 736, when Michiyo’s sons, Katsuragi and Sai, formally adopted the name; both men were direct descendants of Emperor Bidatsu through their father, Prince Minu.

Initially, the Tachibana seemed to be on course to be one of the main players in Heian Court politics. Though Sai died early, his brother, Katsuragi (who changed his name to Tachibana no Moroe), would rise to high office in the Imperial Government, securing the family’s influence in the short term.

Unfortunately, as is so often the case, the son did not prove the equal of the father. Moroe was succeeded by his son, Tachibana no Naramaro. Though Naramaro was granted high office at first when Emperor Shomu retired and was succeeded by his daughter, Empress Koken, Tachibana’s influence was suddenly under threat.

Koken is another character who deserves an entire post of her own, but the short version is that she favoured and was supported by the Fujiwara under Fujiwara no Nakamoro. Taking advantage of this, Nakamoro acquired lands, wealth, and titles that increased his wealth and power still further.

Nakamoro’s rise was not without opposition; however, even amongst his own family, jealous cousins and siblings plotted against him, but it was the Tachibana who had the most to lose by his rise and the most to gain from his potential fall.

In 755, in response to some drunken slander, Tachibana no Naramoro was forced to retire by Fujiwara no Nakamoro and his supporters at court. When Naramoro’s father, Tachibana no Moroe, died in 757, Naramoro, now in control of the Tachibana Clan, made his move.

Allying themselves with Nakamoro’s disaffected sibling, Fujiwara no Toyonari, the Tachibana planned to raise troops, storm the capital, and overthrow the Fujiwara and their puppet Emperor, replacing them with Tachibana dominance, and putting a more sympathetic Imperial Prince on the throne.

Unfortunately for the Tachibana, the conspiracy was uncovered, and the conspirators were arrested. Those of Fujiwara blood were sentenced to exile in Kyushu, but Tachibana no Naramoro was sentenced to death. Despite pleas for clemency, they were executed sometime in 757, although the official records of how Naramoro died have been lost.

The power of the Tachibana at court would never recover, though they would continue to hold positions in the government. The rise of the Fujiwara proved to be inexorable, and the Tachibana were soon eclipsed. The last ‘hurrah’ of the family appears to have been their role in a rebellion in 939 in support of a different Fujiwara.

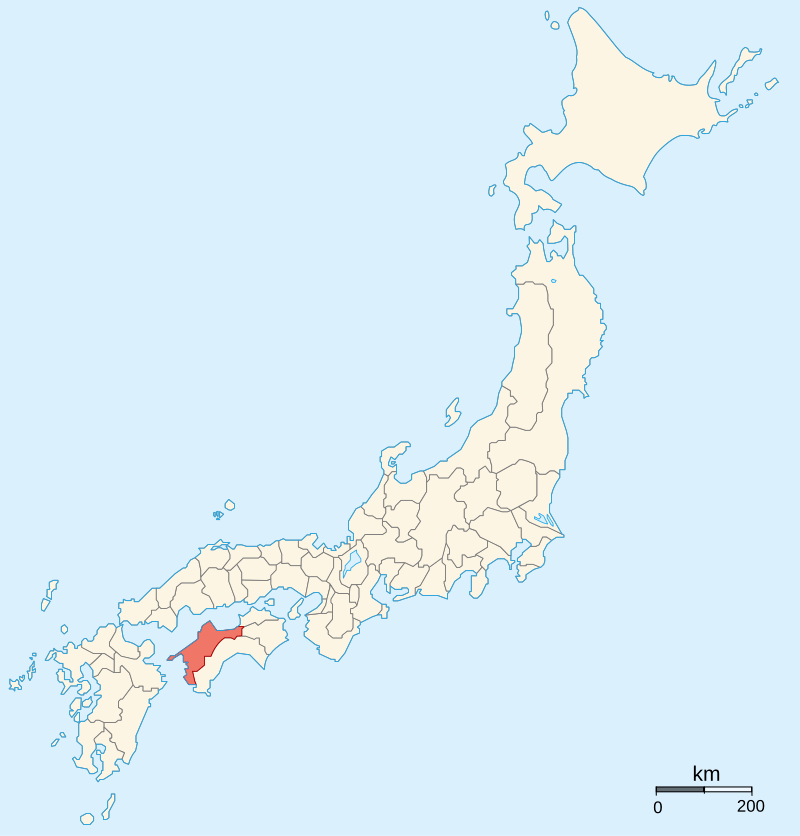

The rebellion was crushed, and those involved were severely punished, but one member of the family, Tachibana no Toyasu, remained loyal to the Emperor and even took part in the execution of the rebel leader. As a reward, he received lands and titles in Iyo Province, where a branch of the family would survive a while longer, but the days of Tachibana influence at court were over.

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1682518

A final note: there was a Samurai clan called Tachibana based near modern Fukuoka; however, the name is a coincidence, and the later Tachibana were no relation to the Heian Period family.

Incidentally, this Tachibana family are still there, and they run a ryokan (traditional Japanese inn) based in their ancestor’s former residence.

Taira

Much like their contemporaries, the Taira began with grandsons and great-grandsons of several Emperors, and despite the shared name, there were actually four branches of the Taira family that came into being during the 9th Century, and these branches would often split as well. However, for our purposes, it is the line of Taira no Takamochi, founded in 889, that proved to be the most enduring.

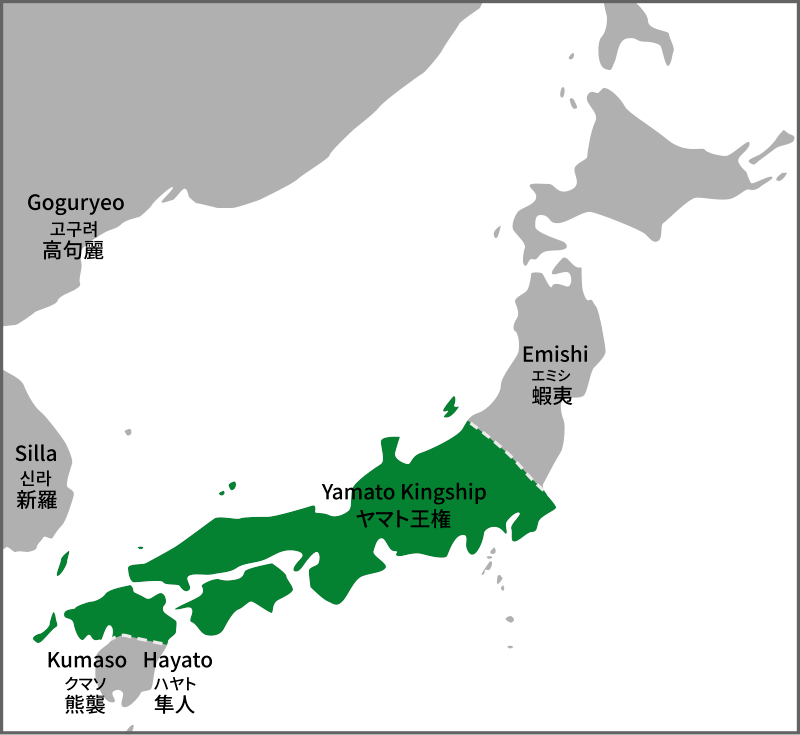

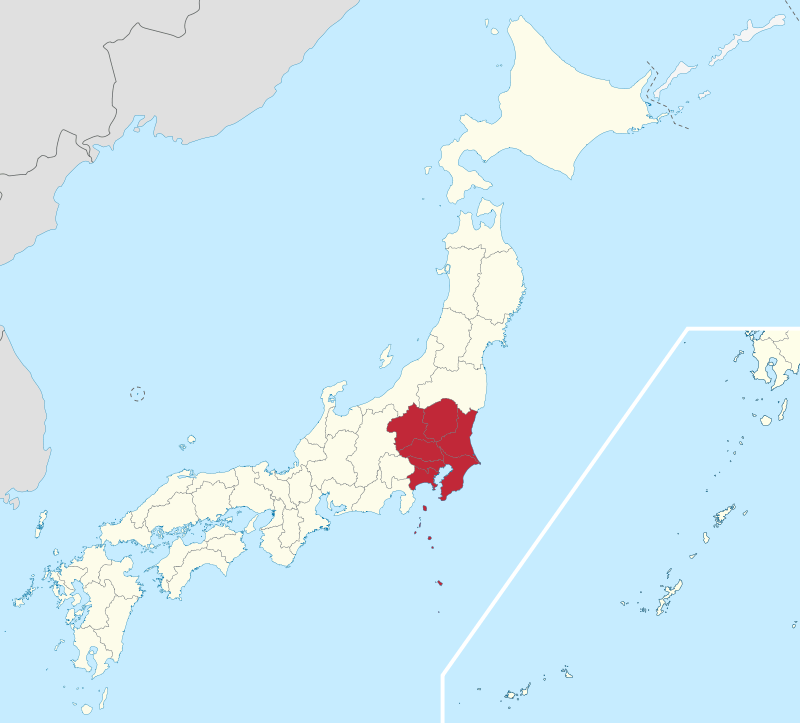

Unlike the Fujiwara and Tachibana, the Taira’s centre of power was not the court at Heian-Kyo but the provinces, specifically the area of the Kanto plain, which includes the area in and around modern Tokyo, far from the Imperial Capital.

By TUBS – This vector image includes elements that have been taken or adapted from this file:, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16385930

This distance meant that Taira influence at court was initially weak, but it worked both ways. Whilst the Taira might have been unable to exert much influence on the throne, the throne was equally unable to exert influence on the Taira.

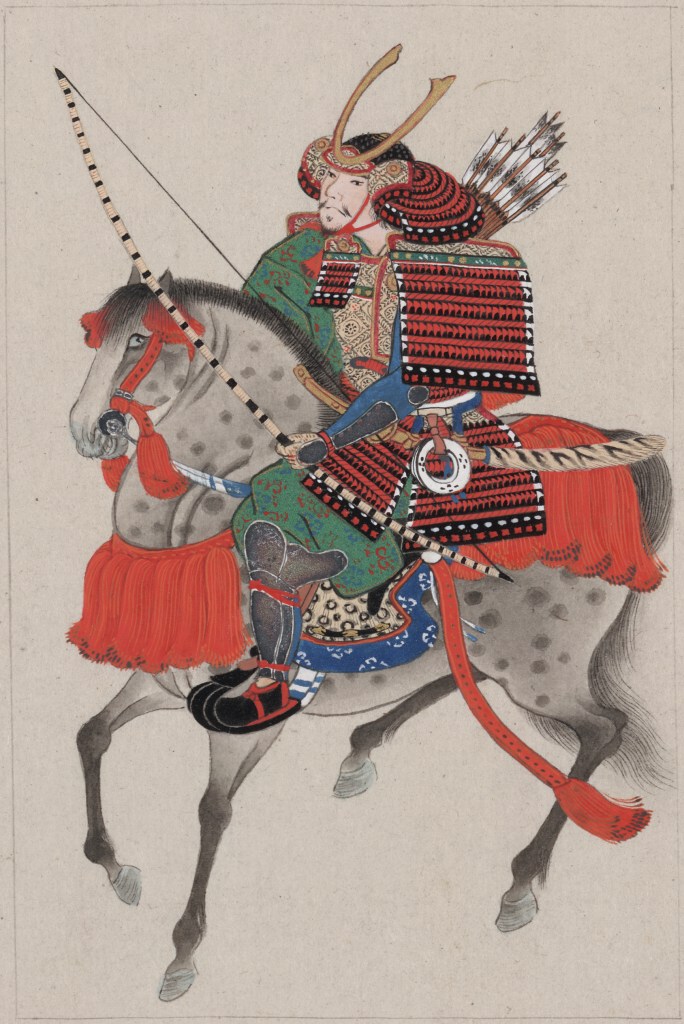

Consequently, as Imperial control waned in the provinces, the Taira were one of the main beneficiaries, gaining control of vast swathes of farmland and the wealth and power that went along with it. They would also begin to gather large groups of armed men to their service, and by the 10th Century, they were the dominant power in the East.

The Taira would put this wealth and power to good use, engaging in local feuds without landholders and growing their already considerable resources through the application of force; though some of their opponents would appeal to the Emperor, there was little the Imperial Court could actually do about it, and as long as the Taira focused their efforts on their neighbours, the Court seemed content to turn a blind eye.

Enter Taira no Masakado. Masakado’s life has been the subject of a lot of dramatisation over the years, so it’s not always possible to figure out exactly who he was or what he did. However, he appears to have gone to Heian-kyo in his late teens, hoping to gain an official position.

He was out of luck on this score and returned home. There, if the stories are to be believed, he got into a dispute with his uncle over a woman, who may have been his daughter (Masakado’s cousin) or maybe not; again, the sources don’t agree. Another source says that there was a woman, but she was instead the daughter of Minamoto no Mamoru, a powerful local rival to the Taira.

Still, more sources don’t mention a woman at all, stating that the conflict began as a result of a land dispute, with Masakado’s supposed inheritance being taken by another member of the family.

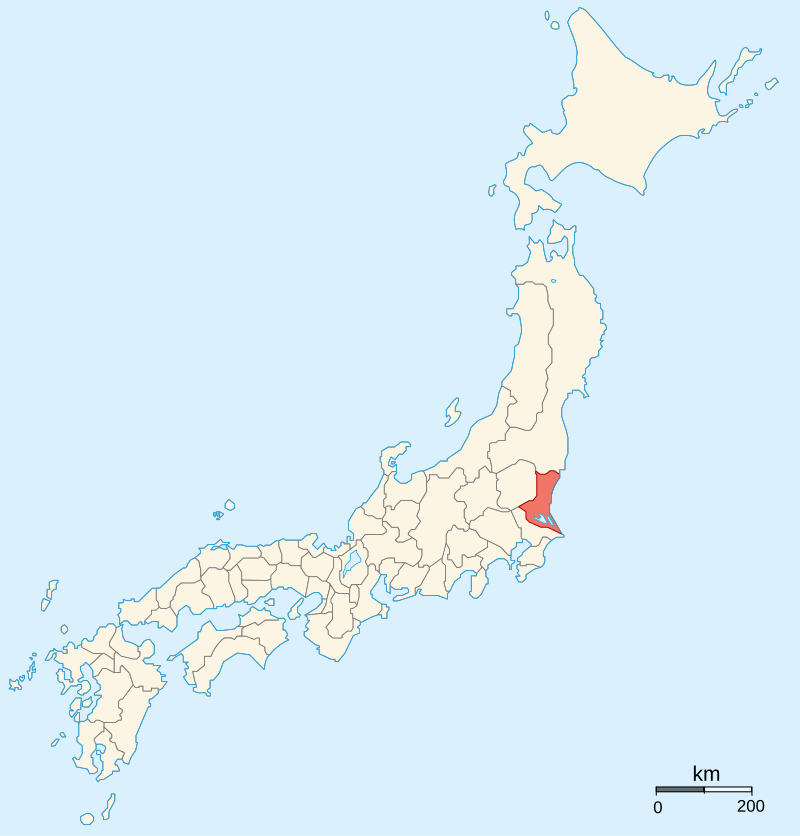

While the background reasons are likely to never be known for certain, in early 935, Masakado was ambushed somewhere in Hitachi Province, modern Ibaraki Prefecture, by the sons of Minamoto no Mamoru. Masakado survived the attack, fighting off and killing his attackers, and responded by going on a rampage throughout Hitachi Province, burning the homes of his enemies, including the Uncle who he was in dispute with (either about land or his cousin.)

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1682357

The situation spiralled out of control from there, and there was a series of battles in which Masakado generally prevailed. His enemies called in support from nearby provinces, and though they outnumbered Masakado considerably, he won a series of victories and drove his foes back to their residences.

At this point, Masakado seems to have been worried about official consequences (because the bloodshed so far was fine, I guess.) At this point, Masakado limited himself to lodging a formal complaint, and when he was summoned to the Imperial Court to explain himself, it was declared to have been a local matter, and all involved were pardoned.

Now, you might think that official censure would be enough to put the matter to rest, but you’d be wrong. It turns out that if you let powerful local landowners build up their own private armies, they tend to be less keen on obeying central authority.

Almost as soon as Masakado returned to his province, the fighting resumed. Those who Masakado had defeated now sought revenge and attacked him. This time, it seems Masakado was defeated, and several of his holdings were burned.

Exactly what led up to the events that followed isn’t clear, but by the end of 939, Masakado had gotten into further disputes with local officials, and he went as far as attacking the provincial headquarters, burning it to the ground, and looting the official storehouses.

Now, the Imperial Court was pretty ineffectual by this point, but this was a direct attack on their authority, and even the decadent Heian Court couldn’t ignore that. The problem was, what to do about it? There was no Imperial Army, so the court had to rely on the very same local landowners that Masakado had been feuding with in the first place.

Masakado was declared to be in rebellion, and a coalition army led by Fujiwara no Hidesato, Minamoto no Tsunemoto, and Taira no Sadamori (Masakado’s cousin) crushed the rebels in 59 days.

Despite dealing with the rebellion relatively easily, the outcome was actually highly problematic for the Court. Although the Rebels had been beaten, it had been local leaders who had done the actual fighting, and even though Masakado had been a Taira, it had been Taira who had played a major role in his defeat.

It would be some years before the full consequences of this would be felt, but the Taira would remain in place in the East, now with the added assurances that their military strength was not only secure but necessary.

Minamoto

So, we move on to the third part of our story today. The Minamoto are last, but most certainly not least, when it comes to discussing the major powers of the Heian Court.

Like the other great families, the Minamoto got their start when sons and grandsons of Emperors were granted their own houses as a way to compensate them for never being able to sit on the throne. Whilst the Fujiwara, Taira, and Tachibana would spread across the Japan, the Minamoto were the proverbial weeds.

No fewer than 21 separate branches of the family were created, and although a few would die out within a generation or two, others became central to the history of Japan, with one, the Seiwa Branch, proving to be truly significant indeed.

Given the sheer number of branches of the Minamoto Family, it isn’t possible to write a history of them that would be concise enough to be readable. Given that I don’t expect you to sit there and read for the next three or four months, we’re going to condense a lot of this information, as a lot of overlaps with events we’ve already discussed, and, as you’ll see, the Minamoto will become extremely important in the latter days of the Heian Period.

Generally, the Minamoto were a family that is closely identified with the decline of Imperial authority in the provinces. Whereas the Fujiwara and Tachibana concerned themselves with court politics, the Minamoto, like the Taira, focused on building their powerbase away from the capital.

In many ways, the Minamoto best represents the growing shift in the power dynamic. Although the Fujiwara were largely unchallenged at court during this period, they would be forced to call on the Minamoto to use their military resources to deal with problems in the provinces. Indeed, during Masakado’s rebellion that we mentioned earlier, it was Minamoto forces that played a large role in his defeat.

Later, it was the Minamoto brothers, Yorinobu and Yorimitsu, who were in the service of the Fujiwara, acting as their enforcers in the provinces. Yorinobu’s son, Yoriyoshi, would lead ‘Imperial’ forces against the rebel Abe Clan in northern Japan during the so-called “Nine Years War”, so named despite lasting Eleven Years.

Such was the prowess of the Yorinobu’s grandson, Yoshiie, that he was nicknamed “Son of the God of War”, and the martial reputation of the Minamoto was secured.

By the 11th Century, Japan was divided between rival warlords whose power no longer derived from the Imperial court. They would settle their own matters, often with steel, and the 11th Century would see the nadir and eventual end of the Heian Court’s dominance.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minamoto_clan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minamoto_no_Yorinobu

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minamoto_no_Yorimitsu

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minamoto_no_Yoriyoshi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minamoto_no_Yoshiie

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Former_Nine_Years%27_War