This is the 50th post on this blog. Well done for getting this far.

In 1565, Date Harumune retired and handed control of the clan over to his son Terumune. Despite this, Harumune held onto the real power, and it wasn’t until 1570, when Terumune accused several of his father’s supporters of treason and had them removed, that he gained actual power.

Despite this, Terumune continued most of his father’s policies, especially in diplomacy. The alliance with the Ashina Clan was maintained, and Date diplomats reached out to the Hojo, Oda, and Shibata Clans, establishing friendly relations with several of Japan’s most powerful warlords. The Sengoku in Sengoku Jidai literally means ‘country at war’; however, alongside his diplomatic efforts, Terumune showed he wasn’t afraid to throw his weight around if an opportunity presented itself.

In 1578, the death of Uesugi Kenshin presented just such an opportunity, and Terumune dispatched forces to intervene in the internal struggle that followed. The Date intervention was ultimately unsuccessful, largely due to the military skills of the Shibata Clan, vassals of the Uesugi, who fought off the Date in several engagements.

Frustrated, Terumune withdrew, but the Shibata had apparently expected more generous rewards for their service, and in 1581, when it was clear that they would not beforthcoming, the Shibata rebelled. Terumune dispatched his army once again, this time in support of the Shibata, and the conflict within the Uesugi Clan would drag on for years.

さどこ – http://blog.livedoor.jp/sadosado_4hi/archives/8412806.html, CC 表示-継承 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=99877267による

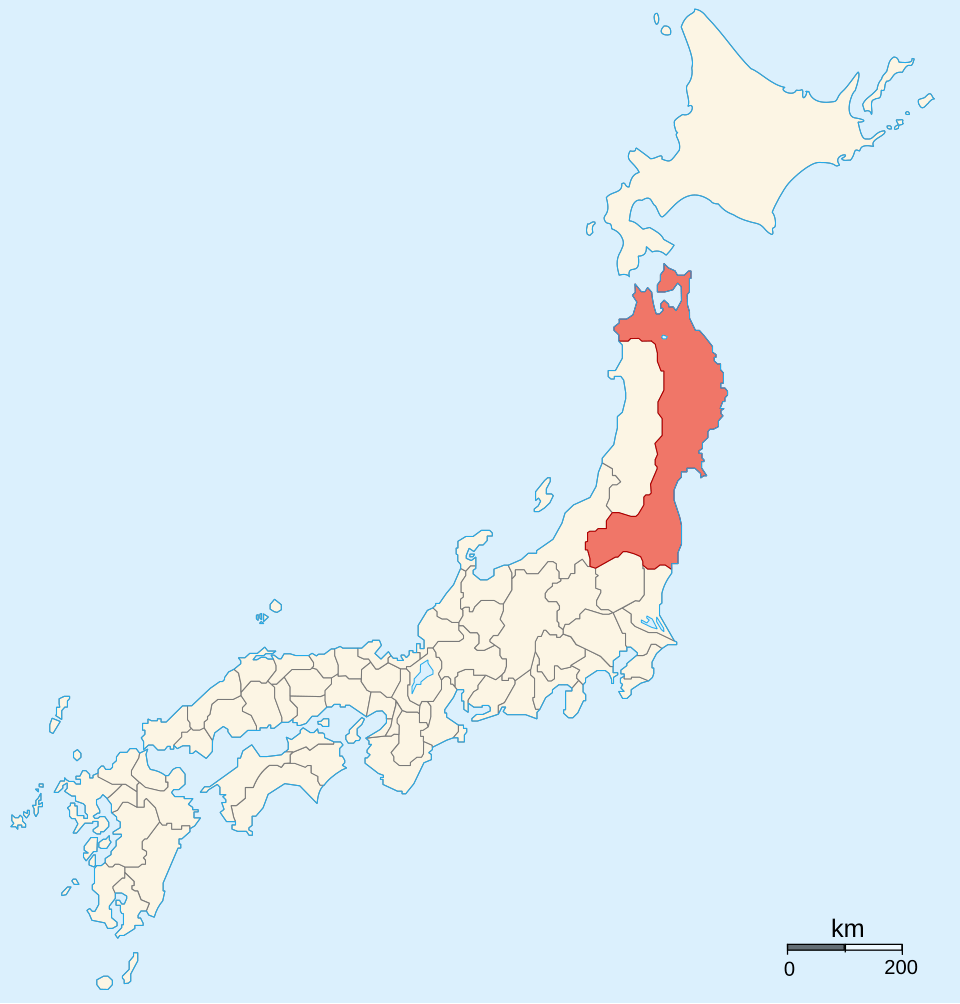

Closer to home, the long war against the nearby Soma Clan continued into Terumune’s reign. The Soma were based in southern Mutsu Province (the area of modern Fukushima Prefecture) and had proven to be tenacious opponents of the Date, with neither side ever able to establish a permanent advantage over the other, despite decades of conflict.

In the period of 1582-84, however, the Date finally managed to overcome the Soma. Although the latter clan was not completely subdued, the strategic situation compelled them to make peace in 1584, with the border between the two clans agreed upon by treaty.

Also in 1584, the long-time allies of the Date, the Ashina Clan, fell prey to an internal power struggle, after their lord, Moritaka, was murdered by a retainer (the official reason is said to be ‘due to sodomy’, so make of that what you will). The new head of the clan was just a month old, and so the Ashina were effectively subordinate to the Date, despite nominally remaining independent.

Shortly after this, Terumune retired, handing leadership over to his son, Masamune. Sources disagree on the exact reason for this, with some suggesting that Terumune planned to make his second son head of the Ashina, only to encounter serious opposition from within the Ashina and his own clan, who then forced him to abandon the idea and retire in disgrace. Other sources say that Terumune learned a lesson from the fate of the Ashina and decided to hand over the leadership of the Date to his son while he was still alive, rather than leave the succession to chance.

Regardless of the reason, Masamune became head of the clan in 1585, and immediately set out to prove that he was not going to do things the same way as his father had. Whilst Terumune had intended to continue the war against the Uesugi, along with his Ashina and Mogami allies, Masamune made peace, without consulting either clan, leading to a sudden and serious decline in relations.

Masamune would definitively end the alliance shortly afterwards when he invaded Ashina territory, which the Ashina, unsurprisingly, interpreted as a hostile act. The invasion would prove to be a back-and-forth affair, with the Ashina successfully repelling the Date’s first attacks only to be defeated by a second wave, led by Masamune himself.

In late 1585, the Ashina asked for a truce, and a peace was mediated by Terumune and his uncle, Sanemoto. The negotiations would prove to be a ruse, however, as Ashina forces kidnapped Terumune at sword point and tried to escape back to their own territory. What happened next is a matter of debate; some sources state that Terumune, seeing that he couldn’t escape, ordered the pursuing Date forces (his own men) to open fire with their bows, killing the entire party, including Terumune.

Another source suggests that the Ashina, trapped by the Date pursuit, killed Terumune themselves, and were then cut down. A third source (written later) states that Masamune himself was responsible for Terumune’s death, and may have orchestrated the whole thing to get rid of his father. Though the exact circumstances will never be known, Terumune’s death also signalled the end of serious attempts to end the local conflicts through negotiation.

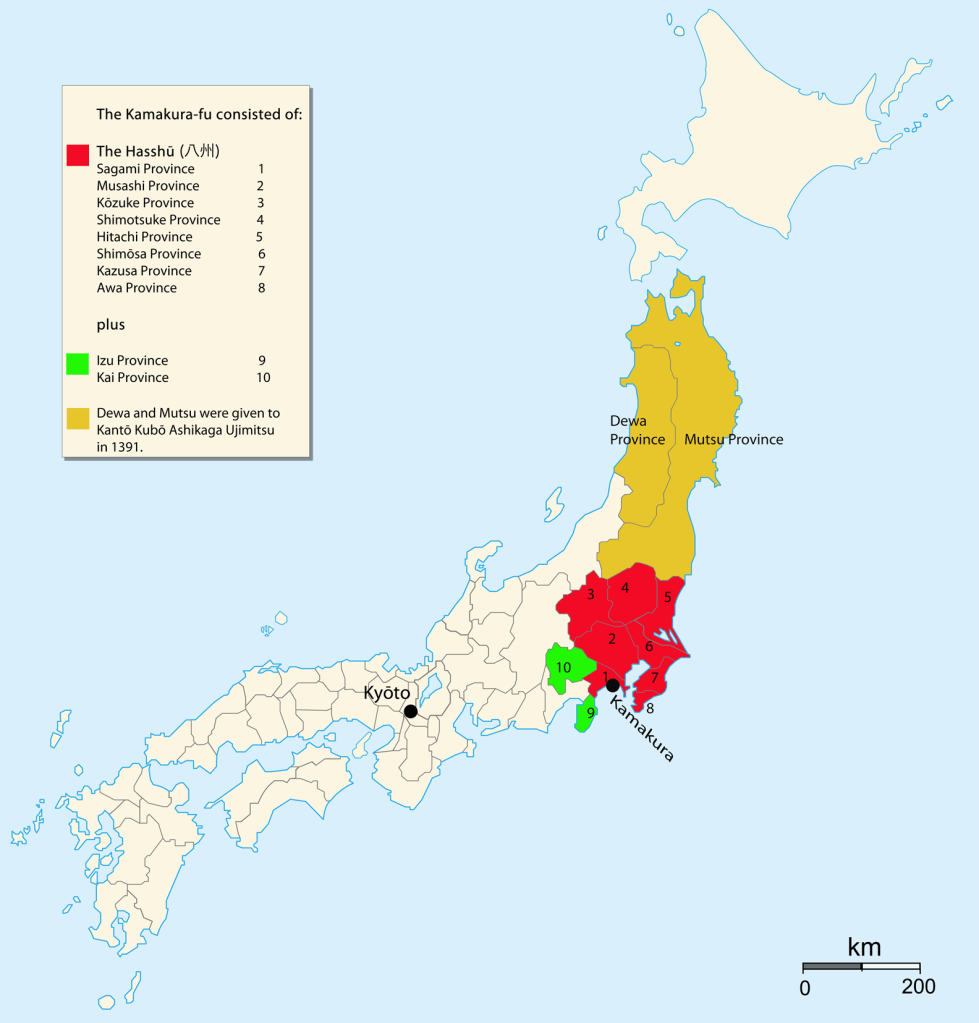

Shortly after his father’s somewhat controversial death, Masamune continued the war. In January 1586, he laid siege to Nihonmatsu Castle (in the city of the same name, in modern Fukushima). At this time, an army led by the Satake Clan, from Hitachi province (to the south), arrived to relieve the castle. The Date were defeated at the Battle of Hitotori Bridge, and Masamune himself was badly wounded before a rearguard action allowed him to escape.

baku13 – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC BY-SA 2.1 jp, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11354374による

The defeat was evidently not serious, because only a few months later, after the Satake had withdrawn, Masamune tried again, once again besieging Nihonmatsu Castle, forcing its surrender in July. Not long after this, he negotiated a peace with the Satake with the intention of focusing his efforts on finishing off the Ashina. This peace was short-lived, even by the standards of the day, as a succession crisis within the Ashina Clan drew the attention of the Satake, who supported a rival candidate to Masamune’s preferred choice.

Masamune interpreted this as the Satake intending to bring the Ashina under their control, which would have put the Date in an extremely vulnerable situation. In response, he declared his intention to wage a full-scale war against both the Ashina and Satake. In 1587, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, by now acting as regent, issued an order that all private wars should halt, an order that Masamune, for now at least, ignored.

Masamune initially had reason to regret his continued belligerence. In 1588, his old enemies, the Mogami Clan, took advantage of Masamune being distracted elsewhere and invaded Date territory at the same time as the Ashina Clan attacked in the south. After defeats at the Battle of Osaki and then at Koriyama, Masamune was obliged to seek peace with both clans, stabilising the situation in the short term.

In 1589, the peace with the Ashina Clan broke down once again, with Masamune invading the Aizu region (in the west of modern Fukushima). Masamune won a decisive victory at the Battle of Suriagehara in July 1589, causing the Ashina to flee their home castle at Kurokawa (modern Aizuwakamatsu) and seek help from the Satake. The Satake were obeying Hideyoshi’s peace order, however, and no help was forthcoming. Shortly after this, Masamune moved his base to Kurokawa Castle, and when a second order from Hideyoshi arrived, threatening direct intervention, Masamune took the opportunity to make peace.

A year later, Hideyoshi ordered the Date to join him in his attack on the Hojo Clan at the siege of Odawara. This put Masamune in a difficult spot, since the rule of his father, Terumune, the Date and Hojo had been nominal allies, and when Hideyoshi’s order arrived, it wasn’t immediately clear which side Masamune would join. Masamune eventually marched in support of Hideyoshi, but the regent wouldn’t forget Date disobedience of his peace order.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E6%94%BF%E5%AE%97

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B1%8A%E8%87%A3%E7%A7%80%E6%AC%A1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%91%BA%E4%B8%8A%E5%8E%9F%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%8B%A5%E6%9D%BE%E5%9F%8E

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BA%8C%E6%9C%AC%E6%9D%BE%E5%9F%8E

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BD%90%E7%AB%B9%E6%B0%8F

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hitachi_Province

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aizu

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E8%BC%9D%E5%AE%97