This post is coming out on Christmas Day, so Merry Christmas (if that’s your thing).

We’ve taken a look at the Hojo before, their origins, and their founder, Hojo Soun, featured in a post I wrote a while back, which can be found here:

Mukai – コンピュータが読み取れる情報は提供されていませんが、自分の作品だと推定されます(著作権の主張に基づく), CC 表示-継承 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9416708による

In brief, the Hojo, as they became known, were originally called the Ise, and their founder, Soun, invaded Izu Province in 1493 before conquering Odawara in neighbouring Sagami Province in 1495. It was Soun’s son, Ujitsuna, who adopted the name and mon of the Hojo Clan, who had been the de facto rulers of Japan during the late Kamakura Shogunate.

Exactly why he chose to change the clan’s identity is a matter of some debate, with the most obvious reason being the prestige the name brought, which would help to convince the clans that were ‘native’ to the area that the Ise (now the Hojo), who had originated elsewhere, belonged.

The Hojo based themselves permanently at Odawara from around 1516, and it is from there that Ujitsuna, the second lord (or first, if you’re feeling pedantic about names), would rule. After Soun passed the rule to him in 1518, Ujitsuna set about quite literally making his mark on Sagami Province. He was something of a prolific builder and established or rebuilt several famous shrines that still stand today.

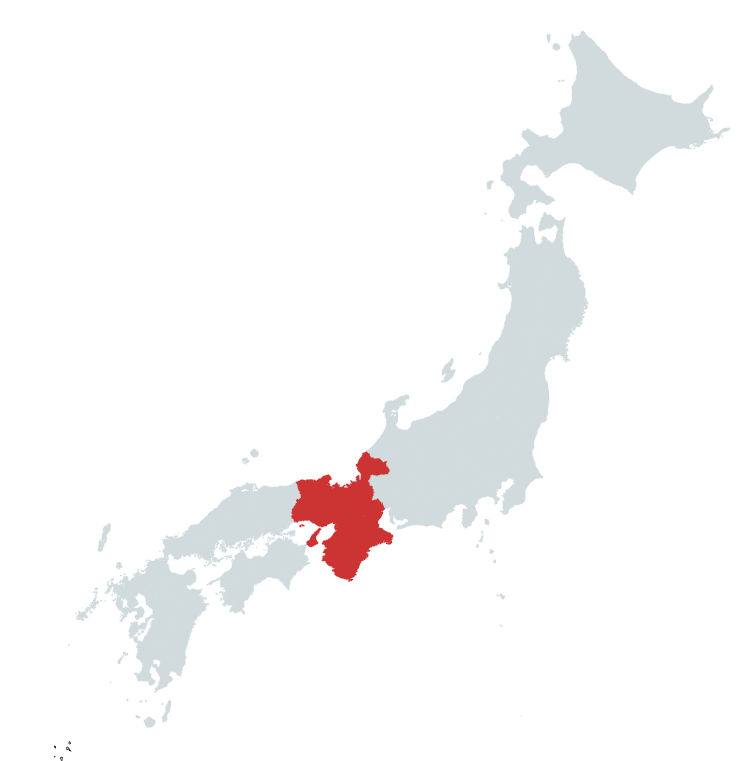

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image: Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1691750

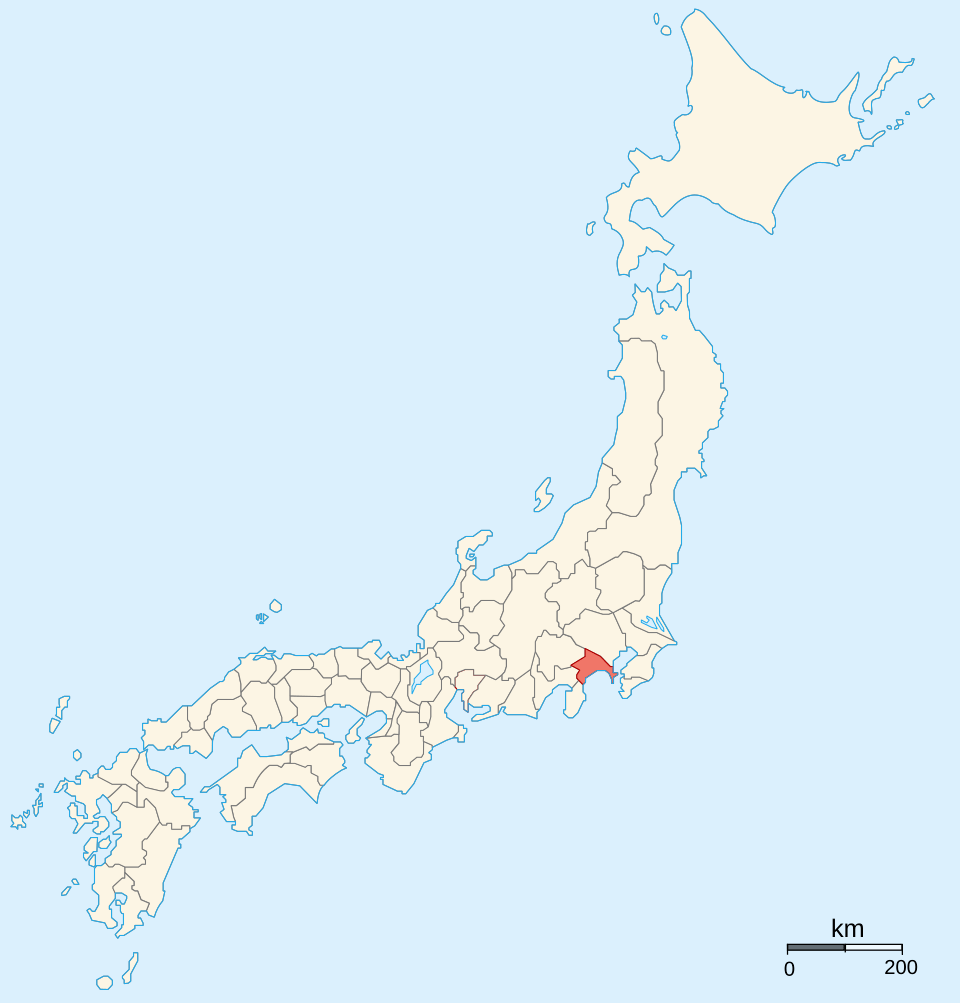

After 1521, Ujitsuna also began to call himself the shugo (governor) of Sagami Province. Officially, he was never bestowed with this title by the Shogun, but by this point, it hardly mattered; no one in Kyoto was in a position to stop him, and Ujitsuna ruled as governor, in fact if not technically by law.

It’s also around this time that the Ise Clan became the Hojo Clan. Traditionally, this was seen as just an arbitrary name change, seeking to attach the somewhat lowborn Ise to an illustrious name. More recent evidence suggests that it might not have been so cynical a move, with some sources suggesting that Ujitsuna’s wife, Yojuin, was a descendant of the Yokoi Clan, who were in turn descendants of the original Hojo.

This would still be a pretty tenuous link on its own. Still, shortly after the name change, the Imperial Court rewarded the Hojo with the title of “Saikyo no Daibu“, the same title the original Hojo were bestowed with. We’ve discussed previously how, by this point, Imperial titles were worthless on their own but still carried considerable prestige. This title put the Hojo on the same rank (in the eyes of the court, anyway) as the nearby Imagawa, Takeda, and Uesugi Clans, families with undisputed lineage.

All this suggests that the claim to the Hojo name might not have been all that spurious, but acceptance by the Imperial Court did not translate to being a member of the ‘club’, and certainly, in the case of the Uesugi (the Ogigayatsu Branch, at least), the Hojo were little more than upstarts.

The Sengoku Period was a time when lineage no longer held the same meaning it once did. A clan with an impressive family tree could (and often did) find itself crushed by clans that, by comparison, had no real ancestry and might have once been subordinates. This phenomenon, called Gekokujo in Japanese (which means low overthrows high), was common across the realm in this period, and a clan like the newly dubbed Hojo would set about establishing its rule at the point of a sword.

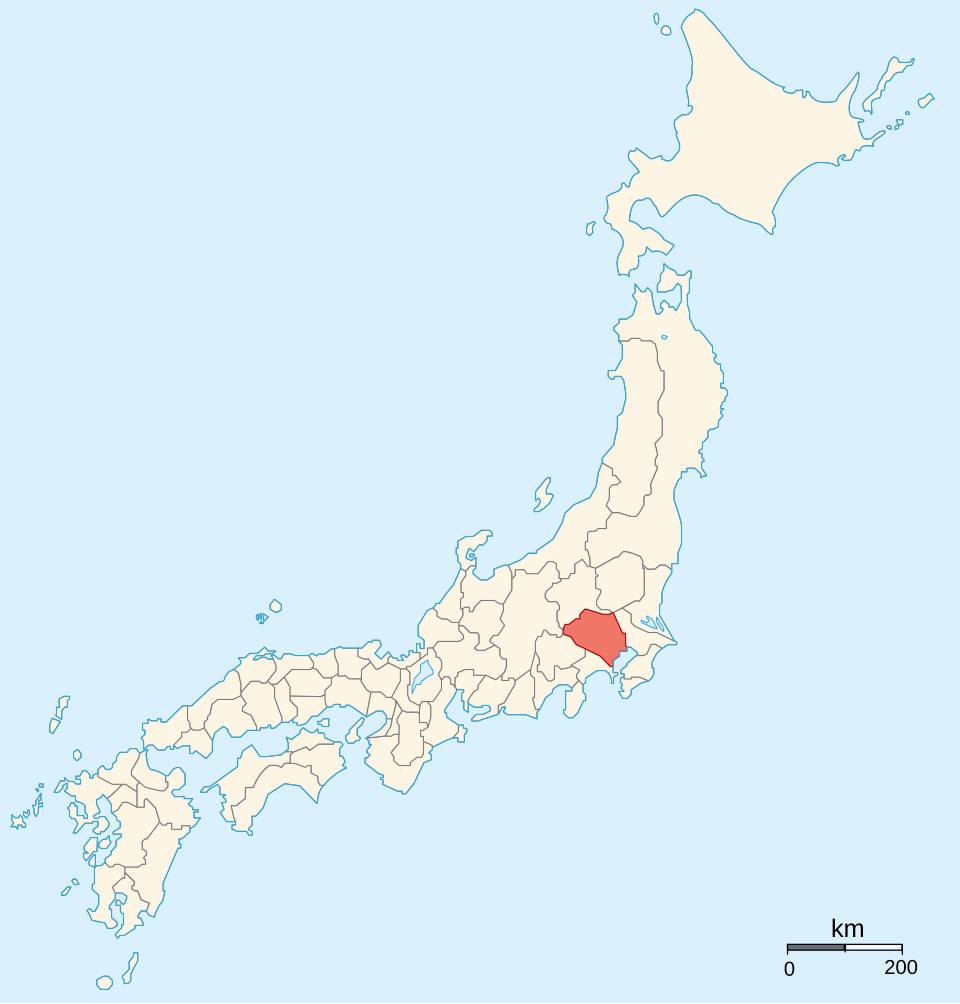

Ujitsuna was very much a man of his time, and by the mid 1520s, he had subdued all of Sagami Province (modern Kanagawa) and advanced into southern Musashi, the neighbouring province, close to the area of modern Tokyo. Faced with further advances by the Hojo and defection of lords in Western Musashi, the Ogigayatsu were forced to respond.

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image: Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1690716

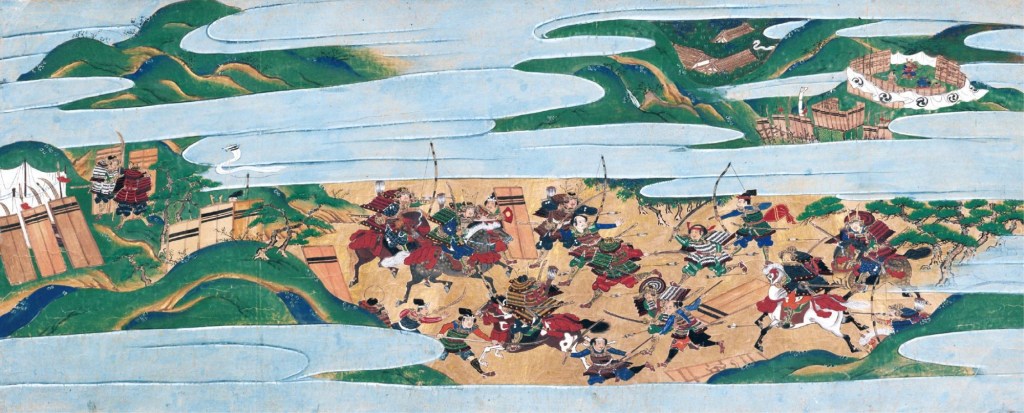

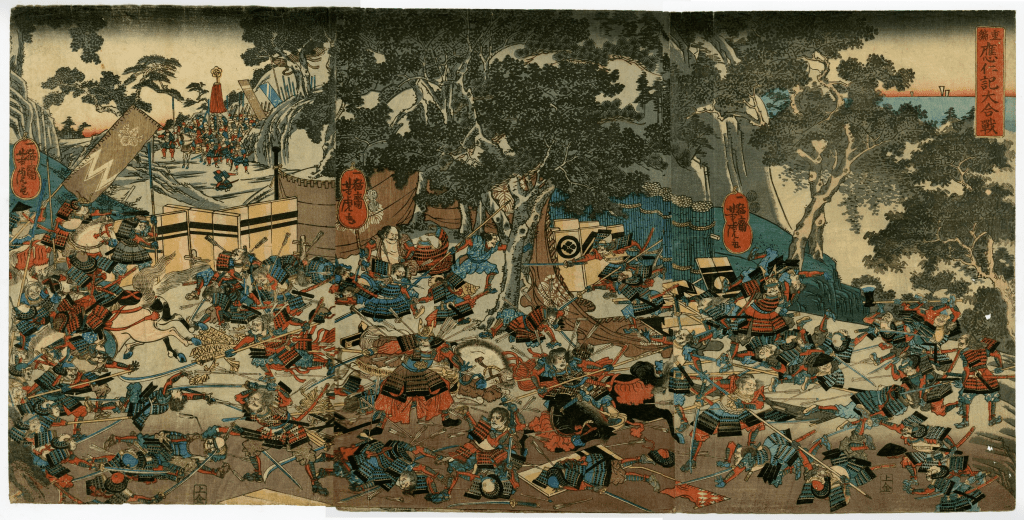

In February 1524, a Hojo force of some 10,000 clashed with the Ogigayatsu at the Battle of Takanawahara. The battle was a decisive victory for the Hojo, with the Ogigayatsu forces retreating to Edo Castle (on the site of the modern Imperial Palace), only for it to fall shortly afterwards, forcing the Ogigayatsu to withdraw further north to another stronghold at Kawagoe.

Ujitsuna, flush with victory, ordered a rapid advance and made rapid progress before a counterattack led by Ogigayatsu ally, Takeda Shingen (remember him?), defeated the Hojo at Iwatsuki in mid 1524, obliging Ujitsuna to seek peace. He would break the peace in early 1525, and despite some early success, the Ogigayatsu, allied with the Takeda, and united with their cousins on the Yamauchi Uesugi, proved to be too much for the Hojo. In September 1525, the Hojo were defeated at the Battle of Shirakobara. Although Edo Castle would hold out, by mid-1526 the Hojo had been driven out of Musashi Province altogether, with Tamanawa Castle on the border of Sagami Province coming under attack in November that year.

The Hojo had their back to the wall, but the forces arrayed against them were a mishmash of different clans, with different goals. A lack of coordination meant that when the time came to attack Sagami in force, the attack was beaten back, with troops of the Satomi (allies of the Ogigayatsu) making it as far as Kamakura before being defeated. During their retreat, they burned the famous Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine. This carried significant political consequences, and Ujitsuna was able to convince the Imperial Court and the Shogunate to censure his enemies.

ulysses_powers から Tsurugaoka Hachimangu in Yukinoshita, Kamakura, Kanagawa – Flickr, CC 表示-継承 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3123909による

This official reprimand created enormous political pressure, and by the end of 1527, Ujitsuna had been able to make peace. Though it is difficult to predict what the outcome might have been otherwise, it is important to remember that Hojo territory faced enemies in three directions, and it is not improbable that, had peace not been agreed, then they may have been overwhelmed.

This reprieve was not wasted by Ujitsuna, either. In 1530, when Takeda forces once again marched against Sagami, the Hojo dispatched a force to meet them. Though the Hojo would prove victorious in this campaign, the Ogigayatsu sought to take advantage of Ujitsuna’s distraction and sent an army of their own, hoping to trap the Hojo army between them and the Takeda.

Standing in their way was Ozawa Castle, controlled by Ujitsuna’s son and heir, Ujiyasu. Sources say that the Hojo were outnumbered as much as 5 to 1, but on the night of July 6th, 1530, Ujiyasu launched a surprise attack on their camp, winning a decisive victory and returning momentum in the war to the Hojo.

多摩に暇人 – 投稿者が撮影, CC 表示 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=93672574による

With this momentum, the Hojo were able to take advantage of the same division that had plagued their enemies a few years earlier. Ujitsuna identified the Satomi Clan (from modern Chiba) as a weak link and focused his attention on them, bribing several family members who were unhappy with the current leadership and seeking to incite a rebellion that the Hojo could exploit.

The plot was discovered, however, and so the Hojo instead relied on good, old-fashioned, brute force, dispatching an army across what is now Tokyo Bay to Awa Province on the southern tip of the Boso Peninsula. Despite the plot’s failure and the execution of several conspirators, some members of the Satomi still rose up in support of the Hojo invasion. What followed was a series of victories as the Hojo-Satomi alliance took castle after castle, culminating in the Battle of Inukake in 1534, which saw the Hojo-Satomi defeat their rivals and replace the head of the Satomi Clan with a Hojo ally.

Whilst the Hojo were victorious on their eastern flank, the western flank was secured by a long-term alliance with the Imagawa. You may remember that Hojo Soun had actually started out as a vassal of the Imagawa, and though the Hojo had since risen to a position of equality with their former masters, the relationship remained close.

With the bulk of his forces busy against the Satomi, Ujitsuna requested his Imagawa ally, Ujiteru, invade Takeda territory to ensure they wouldn’t intervene. The Imagawa obliged and invaded Kai Province in July 1534; they were initially successful but soon became overextended and had to retreat to their home in Suruga. A Takeda counterattack was considered so dangerous that Ujitsuna withdrew forces from the West to face it. The Takeda, remembering their defeat at the hands of the Hojo a few years earlier, tried to lure Ujitsuna into an ambush in the narrow mountain passes of Kai, seeking revenge.

Alpsdake – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45336367による

Ujitsuna was apparently aware of the strategy, however, and dispatched a force to outflank the Takeda, turning the ambushers into the ambushed at the Battle of Yamanaka on September 19th, 1535. The defeat was so severe for the Takeda that the road into Kai province now lay open, and Ujitsuna apparently intended to crush the Takeda once and for all and take the whole of Kai Province for himself.

This invasion was eventually called off as the Ogigayatsu proved to be a more pressing concern, and over the next few years, the geopolitical situation would shift considerably. In 1536, Imagawa Ujiteru died suddenly, aged just 21 or 22. He left no heirs, and so the clan quickly descended into civil war. At about the same time, famine and an epidemic broke out in Kai Province, severely weakening the Takeda.

The Imagawa civil war was won by Yoshitomo, Ujiteru’s younger brother, but the devastation in Suruga left the clan severely weakened, and they sought peace with the Takeda, who, suffering their own calamities, quickly agreed, with Yoshitomo marrying Takeda Shingen’s daughter to establish a new alliance. Ujitsuna recognised that his alliance presented an intolerable risk to his western frontier and resolved to do something about it.

In early 1537, Ujitsuna led 10,000 men into Suruga Province, winning a series of crushing victories over the Imagawa and decisively bringing an end to decades of close relations. Fearing overextension, however, Ujitsuna limited his conquests to the territory east of the Fuji River, and a truce was declared shortly afterwards, which was convenient, as the death of the Ogigayatsu lord left the clan in disarray and presented a golden opportunity for further Hojo expansion, but we’ll talk about that next time.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8C%97%E6%9D%A1%E6%B0%8F%E7%B6%B1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B1%B1%E4%B8%AD%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%AF%8C%E5%A3%AB%E5%B7%9D

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imagawa_Yoshimoto

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%8A%AC%E6%8E%9B%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B0%8F%E6%B2%A2%E5%9F%8E

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B0%8F%E6%B2%A2%E5%8E%9F%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%B6%B4%E5%B2%A1%E5%85%AB%E5%B9%A1%E5%AE%AE

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%99%BD%E5%AD%90%E5%8E%9F%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84