In 1537, Hojo Ujitsuna launched a successful invasion of Suruga Province, establishing the frontier at the Fuji River and ending the threat from the Imagawa-Takeda alliance, at least for now. Shortly after this news broke that (Ogigayatsu) Uesugi Tomoaki had died. Tomoaki had been an implacable foe of the Hojo, and his death severely weakened his clan, which was now led by the 12-year-old Tomosada.

It wasn’t all good news, however. With the bulk of the Hojo forces focused in Suruga against the Imagawa, forces of the Satomi Clan moved to expel the Hojo from the Boso Peninsula (modern Chiba), quickly establishing control and forcing the remaining Hojo loyalists to flee. There was little Ujitsuna could do about that in the short term, but in the summer of 1537, he gathered 15,000 men at Edo Castle before dispatching his son, Ujiyasu, to take the Uesugi stronghold at Kawagoe.

The castle was taken undamaged after a surprise attack, and when the Uesugi tried to recapture it on New Year’s Day 1538, they were defeated. With his northern flank secure, Ujitsuna launched a campaign to reestablish control over the Boso Peninsula. Though they were initially successful, the attack clashed with the plans of the Koga Kubo, Ashikaga Yoshiaki.

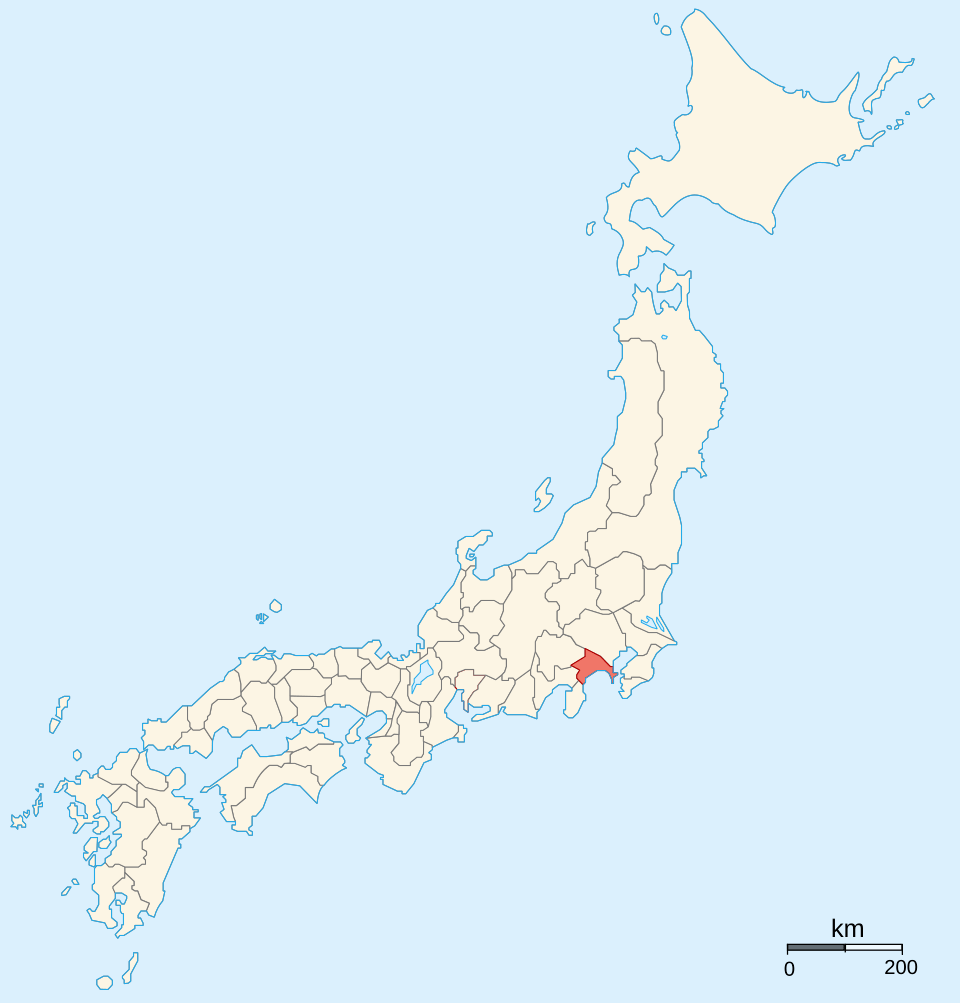

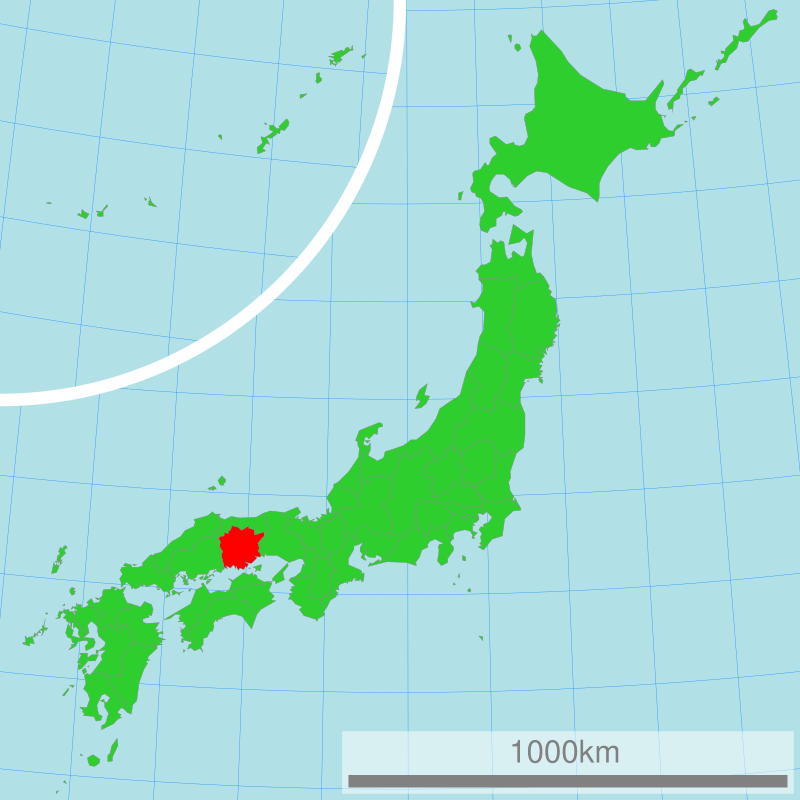

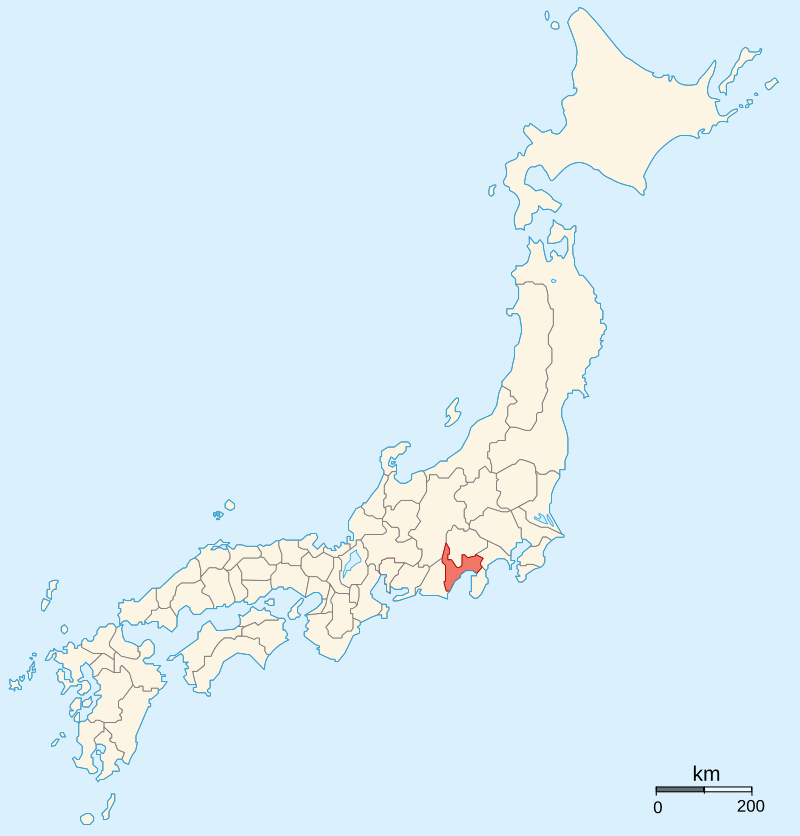

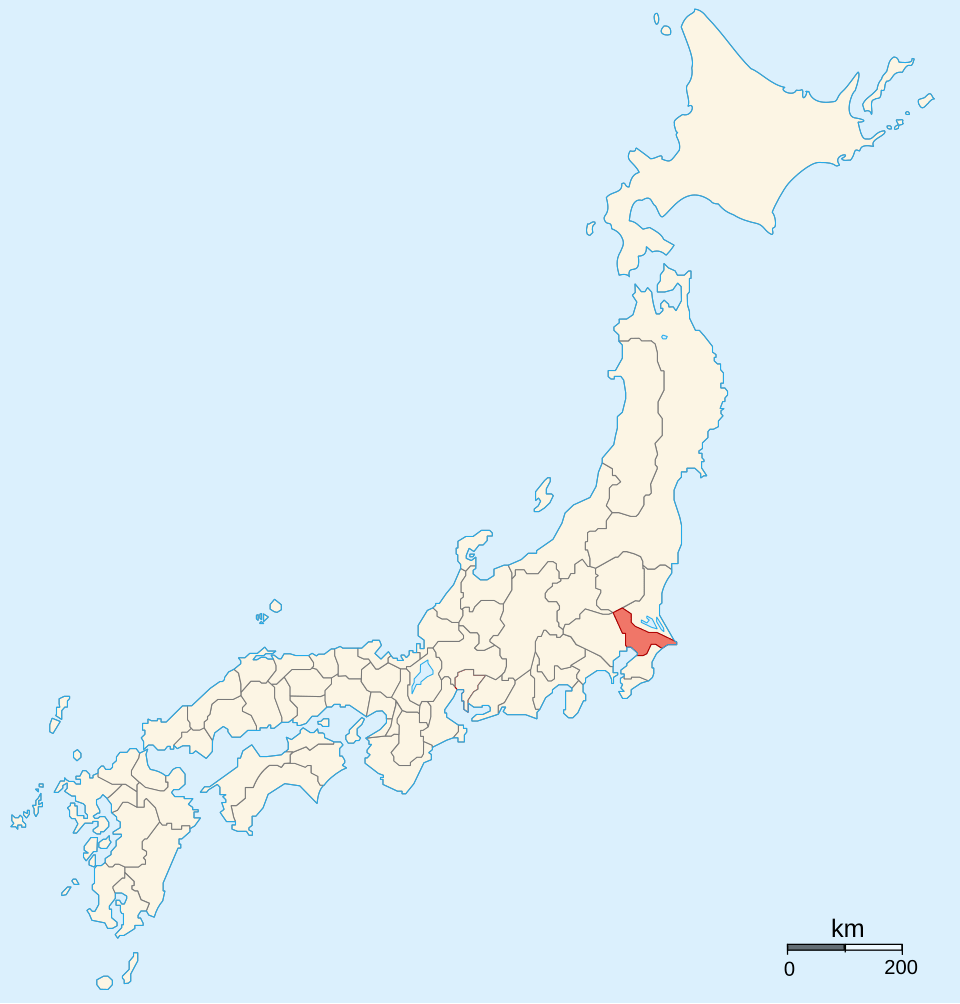

You may remember from earlier posts that the position of Kubo was the Shogun’s deputy in a given area. In decades past, the centre of the Kubo‘s power had been Kamakura, but the catastrophic decline of Shogunate power meant that the Kubo was eventually obliged to leave Kamakura (which was now under Hojo control) and take up residence at Koga, in Shimosa Province (modern Ibaraki).

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image: Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1691764

Yoshiaki had the long-term objective of reestablishing the Kubos’ preeminent position over the whole Kanto, and the Hojo stood in direct opposition to this. Both sides were about equal in strength, but while the Hojo were united behind Ujitsuna, Yoshiaki’s forces were united in opposition to the Hojo, but not necessarily in support of the Kubo.

Though Yoshiaki’s forces agreed to challenge the Hojo at the Edogawa River, they couldn’t decide on a strategy. Yoshiaki’s allies suggested attacking the Hojo as they crossed the river, but sources say that Yoshiaki, proud of his illustrious Ashikaga name, refused such a strategy, deciding that he would march out in person and face the Hojo in the field, once the bulk of their forces were already across the river.

Satomi Yoshitaka, once a supporter of the Hojo but now serving under Yoshiaki, recognised that the strategy robbed them of the advantage of the river and was reluctant to commit his forces to open battle with the Hojo, where victory was far from certain. Yoshitaka also recognised that if Yoshiaki were defeated, a large expanse of territory would become available; thus, he positioned his forces away from what he assumed would be the main battlefield, ready to retreat quickly if things looked to be going badly.

What became known as the Battle of Konodai began on the morning of November 8th, when the Hojo forces crossed the river. Initially, Yoshiaki’s forces had the advantage, but throughout the day, more Hojo forces arrived, and the tide of battle turned. When news came that Yoshiaki’s brother and son had been killed, he flew into a rage and charged the Hojo himself, only to be struck down by an arrow and killed. Seeing this, Satomi Yoshitaka withdrew his unengaged army, and shortly afterwards, the remaining forces began a retreat that swiftly turned into a rout.

The Hojo used the momentum of victory to advance into Kazusa and Shimosa Provinces, whilst Yoshitaka, with his army still intact, would be able to take control of almost the entire Boso Peninsula, where he would continue to resist the Hojo, beginning a feud that would last decades.

Although the exact date is unclear, after the victory at Konodai, Ujitsuna wouldn’t lead another campaign, and scholars agree that he retired as head of the clan sometime in 1539, when his son, Ujiyasu, completed the conquest of Shimosa and Kazusa Provinces. In late 1540, the reconstruction of Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine was completed, and Ujitsuna held a celebration there in which he was recognised as Kanto Kanrei, the Shogun’s official deputy in the Kanto, a title that reflected his preeminent position in the region.

Ujitsuna would eventually pass away in August 1541, and his son, Ujiyasu, lord now in fact as well as name, inherited a strong but dangerous position. Successful campaigns in the east had extended Hojo control to Shimosa province. To the north, the Ogigayatsu-Uesugi plotted revenge and the return of Kawagoe Castle, whilst to the east, the conflict with the Imagawa dragged on, despite a strong frontier on the Fuji River.

A famine in 1540-41 precluded an immediate campaign, and in 1542 Ujiyasu ordered a land survey, which enabled him to adjust and reform taxation in his territory (which was largely based on rice production) and to ensure a strong economic base for what was to come next. In 1545, the Imagawa sent out peace feelers, but no agreement could be reached, and the Imagawa joined forces with the Uesugi, with both agreeing to attack the Hojo from east and west.

Ujiyasu rushed forces to the east, but a combined Imagawa-Takeda army proved too strong, and Ujiyasu was eventually obliged to conclude a disadvantageous peace, which saw him cede all the territory the Hojo had controlled in Suruga back to the Imagawa. Though the new border would remain tense, the peace held, and all three sides would eventually conclude an alliance in 1554, though we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Meanwhile, the Uesugi and their allies had massed a force of some 80,000 men around Kawagoe Castle, and with Ujiyasu busy in Surugu, the castle would endure a 6-month siege. Even after the Hojo had secured peace with the Imagawa, Ujiyasu could only muster 10,000 men, and what happened next is a matter of some debate.

The most common telling is that Ujiyasu, in concert with the garrison inside the castle, organised a night attack on the Uesugi that caught them completely by surprise and routed them in a victory so complete that the Uesugi were destroyed as a serious force in the Kanto. The problem with this version of events is that the only sources describing the battle in that way come from the Edo Period, nearly 100 years after the events.

Scholars debate the accuracy of those reports, and some suggest that the Battle of Kawagoe Castle happened in a very different way, or may never have happened at all, but what is certain is that the siege was lifted and either during the lifting, or shortly afterwards, the lord of the Uesugi, Tomosada, was killed, and the rest of the clan was forced north, leaving Musashi Province in Hojo hands.

The war against the Uesugi would continue, however. In 1550, an attack on Hirai Castle was repulsed, only for a second attempt the next year to succeed, driving Uesugi Norimasa further north, where he sought refuge with Nagao Kagetora (better known to history as Uesugi Kenshin). In the east, too, the Hojo would advance, marching into Hitachi and Shimotsuke Province, and continuing the war against the Satomi of Kazusa Province to their southeast, conquering Kanaya Castle in 1555 and establishing Hojo control over almost the whole of the western Boso Peninsula.

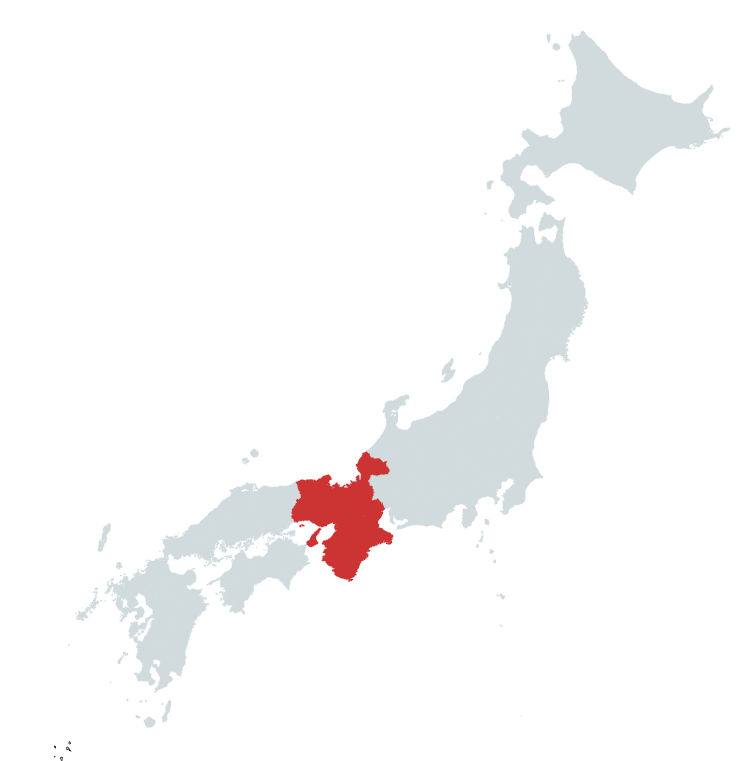

These conquests in the east were possible because of the peace established on the Hojo’s western borders. Though there was no actual fighting, the border remained very tense until the establishment of a triple alliance between the Imagawa, Takeda, and Hojo. This alliance was established over the period 1551-1554, as a series of marriages was arranged among all three parties, culminating in 1554, when Ujiyasu’s eldest daughter married Imagawa Yoshimoto’s eldest son, whilst Ujiyasu’s heir, Ujimasa, married the daughter of Takeda Shingen.

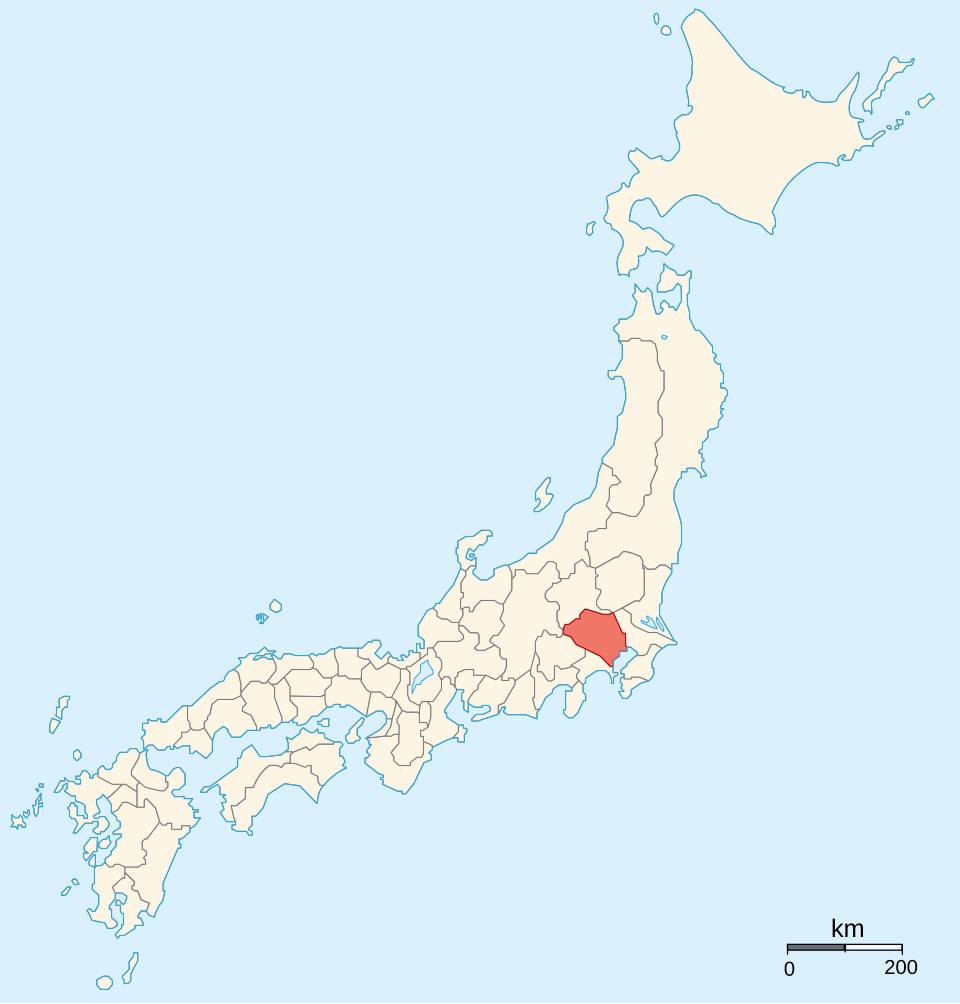

This alliance secured the Hojo’s western border, and in 1559, Ujiyasu retired as head of the clan, handing formal power to his son Ujimasa while retaining actual control himself. That same year, he focused his full attention on pushing the last of the Uesugi clan out of Kozuke Province and established a strong presence at Numata to check any further Uesugi attempts to invade the Kanto.

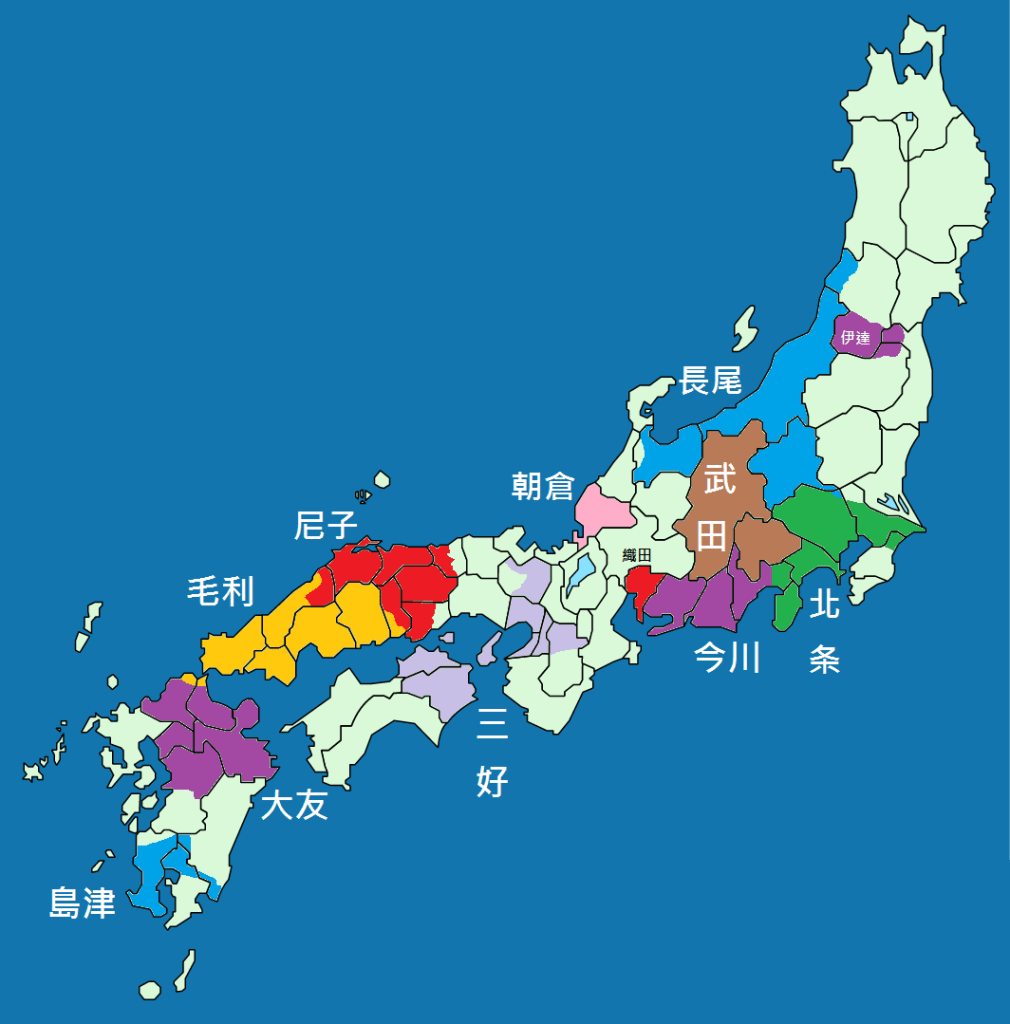

By Alvin Lee – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39200926

In 1560, the Imagawa suffered a serious and surprising defeat at the hands of Oda Nobunaga at the Battle of Okehazama, leaving the clan weak and the Hojo’s western flank reliant on the goodwill of the Takeda. During the same year, another outbreak of famine ravaged Hojo territory, severely weakening their economic power and food supply.

The timing couldn’t have been much worse, because soon, the Uesugi, now led by Kenshin, would return to the Kanto, and the Hojo would face another serious crisis.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8C%97%E6%9D%A1%E6%B0%8F%E5%BA%B7

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imagawa_Yoshimoto

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%9B%BD%E5%BA%9C%E5%8F%B0%E5%90%88%E6%88%A6

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B7%9D%E8%B6%8A%E5%9F%8E

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%B2%B3%E8%B6%8A%E5%9F%8E%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%8A%E6%9D%89%E6%9C%9D%E5%AE%9A_(%E6%89%87%E8%B0%B7%E4%B8%8A%E6%9D%89%E5%AE%B6)

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%BE%8C%E5%8C%97%E6%9D%A1%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%AF%8C%E5%A3%AB%E5%B7%9D

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8F%A4%E6%B2%B3%E5%B8%82

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B9%B3%E4%BA%95%E5%9F%8E