As we’ve looked at previously, internal clan conflict wasn’t uncommon during the 15th century; in fact, it had gotten to the point that violent succession struggles were almost a fact of life. One exception to this rule had been the Hosokawa Clan.

In the mid-15th Century, the Hosokawa were just one of several powerful clans that dominated the area around Kyoto, the centre of political power in the realm. While other clans had risen and fallen throughout the Century, the Hosokawa went from strength to strength, in large part because they managed to maintain a stable succession, leading to one of their number, Hosokawa Masatomo, being strong enough to launch the Meio Coup in 1493, giving him effectively complete control of the government and what was left of its prestige.

The relative stability of the Hosokawa Clan came to an end with Masatomo, however. He had succeeded his father largely because he had been the only viable candidate and had earned the support of his clan’s vassals after his father’s death. Masatomo apparently didn’t learn from this, however. Firstly, his spiritual beliefs meant that he swore off contact with women, which rather limited his opportunities to father an heir.

This was no problem, though; adoption was(and continues to be) a widely accepted custom amongst the rich and powerful in Japan, and all Masatomo had to do was select a candidate who could earn the support of the wider Hosokawa Clan, and their position would be (relatively) secure.

It must have come as quite a shock then, when Masatomo adopted not one, but three sons. To be fair, he didn’t adopt them all at once, and most contemporary sources speculate that his intentions were to split the Hosokawa lands between his new heirs, but you won’t be surprised to learn that it didn’t work out that way.

No sooner was the ink dry on the adoption documents than rival factions began to form around the three potential heirs. Masatomo didn’t help matters by clearly favouring one son, Sumitomo, over the other two, but the whole situation would have been precarious even under the best of circumstances, and the Hosokawa certainly didn’t enjoy those.

We’ve looked at the wide-ranging political problems the Shogunate faced during the latter half of the 15th century, and when Masatomo seized control of the government, he also inherited those problems. It’s hard to see how even the most focused, capable, and diplomatic leader might have reversed the situation the Shogunate found itself in, and unfortunately for the Hosokawa, Masatomo was an eccentric iconoclast, prone to doing things like attempting to fly, deriding long-standing ceremonies, and generally making political enemies wherever he went.

It is a strange quirk of human history, though, that factions who seem to have hostile (and often violent) intentions towards each other will exist in a kind of tense equilibrium as long as there is someone, or something, that they can focus their ire on. In the early 16th century, that someone was Masatomo.

None of the three factions was strong enough to openly oppose him, because if they had, they’d have been attacked and wiped out by the other two, who would need little encouragement to remove a rival, even if that meant supporting Masatomo in the short term.

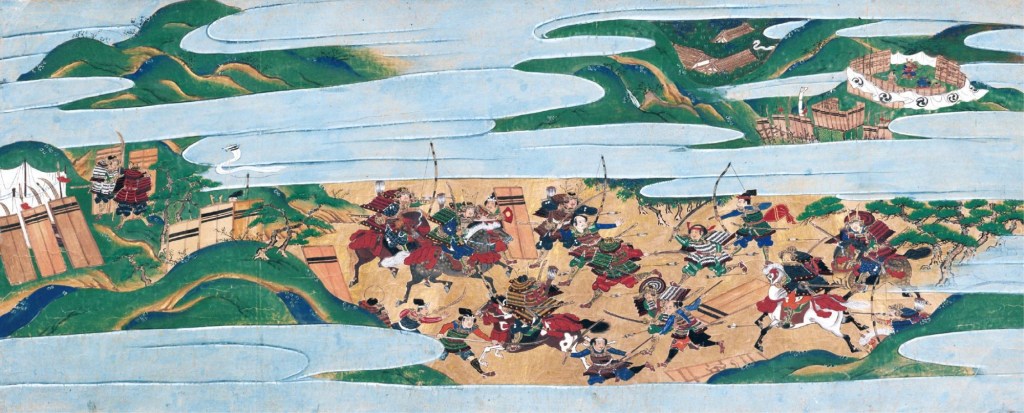

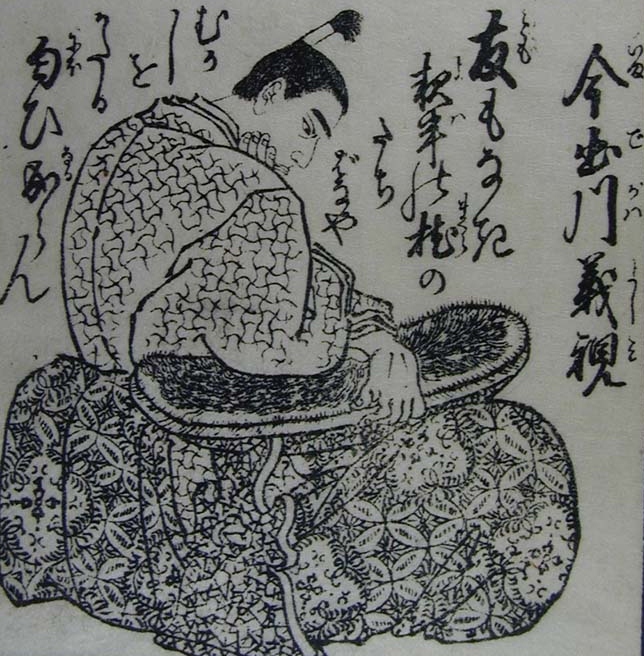

It is also true that, eventually, the dam always breaks, and when it comes to court politics, that usually means blood. In June 1507, supporters of one of Masatomo’s adopted sons (Sumiyuki) assassinated him in his bathhouse. The next day, they attempted to do the same thing to another son, Sumitomo, but he managed to escape with the help of his allies in the Miyoshi Clan.

Just a moment ago, I mentioned that one faction couldn’t make a move without antagonising the other three, and that’s exactly what happened. Sumiyuki’s supporters had tried to remove Sumitomo and failed. Now, Sumitomo fled Kyoto and sought the aid of the third brother, Takakuni, who was only too happy to oblige.

Musuketeer.3 – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24893374による

The combined forces of Takakuni and Sumitomo were indeed too much for Sumiyuki, and by August, he had been defeated and forced to commit suicide. The question then was who would actually succeed Masatomo. Both Takakuni and Sumitomo could arguably claim to have avenged their adopted father’s death, and both had significant support from the remaining Hosokawa retainers.

As we mentioned last time, it is at this point that the previously deposed Shogun, Yoshitane, returned to the scene. Given that Masatomo had overthrown him in a coup and installed a puppet, it wasn’t difficult to convince Shogunate loyalists to side with Yoshitane. Suddenly, becoming heir to the Hosokawa Clan wasn’t quite the prize it had been. Though Sumitomo was in the stronger position, he now faced a resurgent Yoshitane, and his brother, Takakuni, saw the way the wind was blowing and threw in his lot with the returning Shogun as well.

Just as Sumiyuki had been unable to oppose the combined forces of his brothers, Sumitomo did not have the strength to challenge the Shogun and Takakuni. Sumitomo also lost considerable support due to the actions of his supporters in the Miyoshi Clan, who had become overbearing in the short period after their victory.

So, in April 1508, when Yoshitane and Takakuni marched on Kyoto, Sumitomo and the Miyoshi had little choice but to flee with their puppet Shogun, Yoshizumi. Shortly after this, Yoshitane was reinstated as Shogun, and Takakuni was named the new head of the Hosokawa Clan.

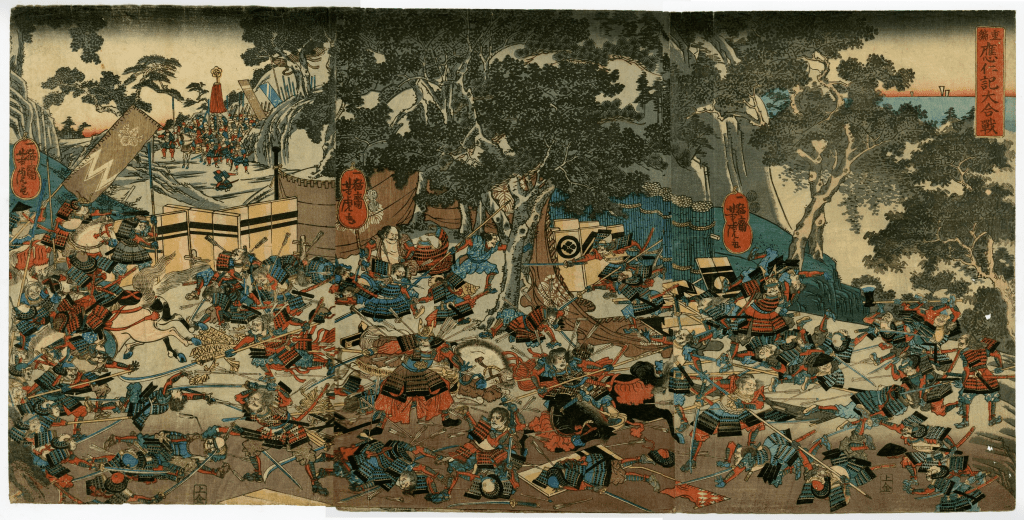

In June the following year, Sumitomo and the Miyoshi attempted to retake the city but were defeated and driven back; however, a counterattack led by Yoshitane was similarly defeated. The back-and-forth nature of the conflict continued until the Battle of Ashiyagawara (sometimes called the Siege of Takao Castle), in the summer of 1511, after which Sumitomo’s victorious forces were able to briefly reoccupy Kyoto.

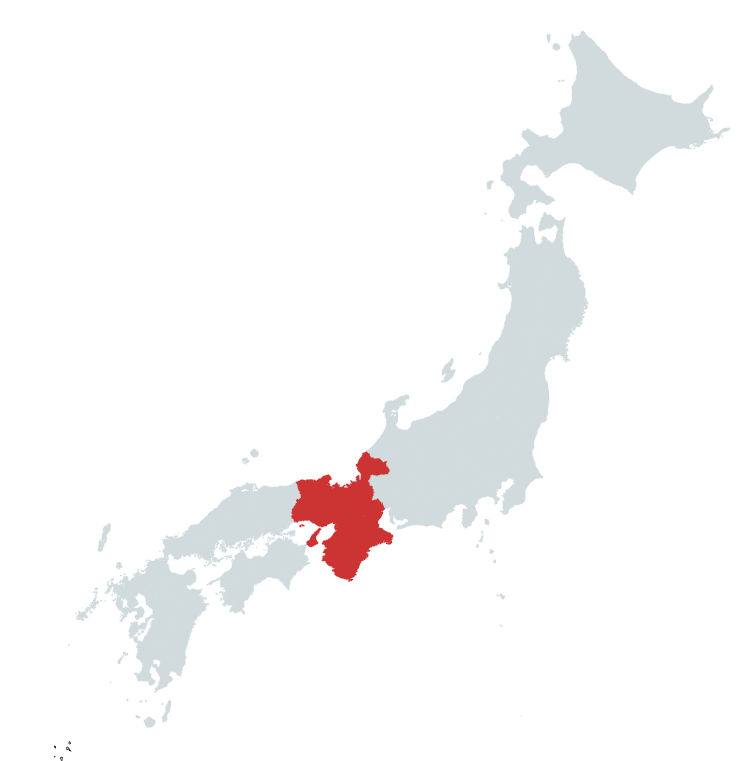

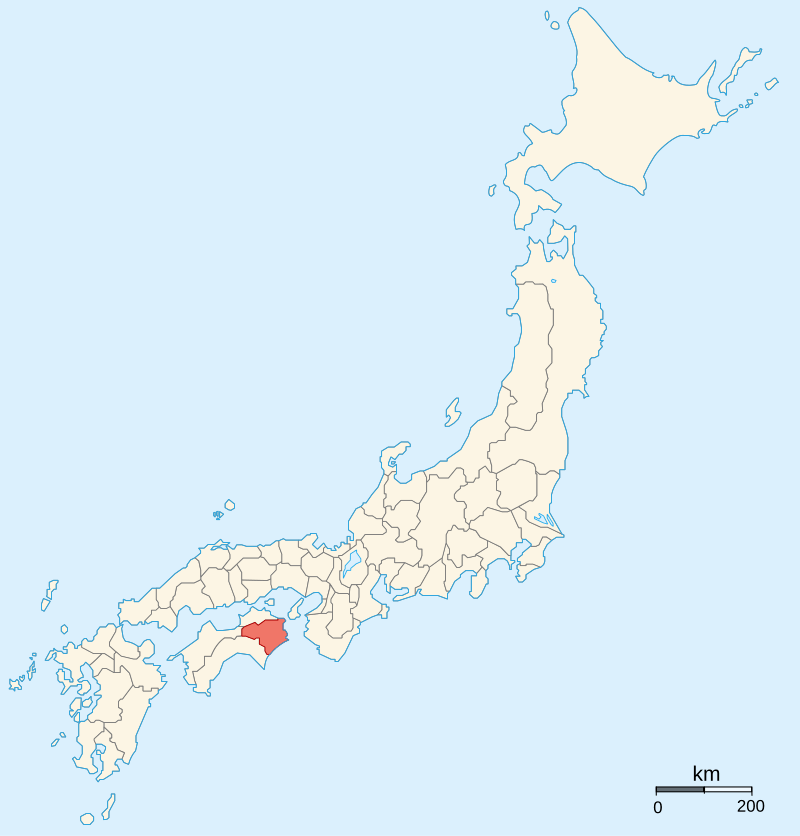

‘Briefly’ is the operative word here, because in September of the same year, Takakuni and Yoshitane’s forces counterattacked, retook Kyoto, and drove Sumitomo and the Miyoshi back to their strongholds in Awa Province, across the Inland Sea on Shikoku.

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1652119

Around this time, Yoshizumi died of illness, and Sumitomo suffered a serious loss of support. Many of his allies had supported Yoshizumi as Shogun, and Sumitomo as his champion, but now Yoshizumi was gone, Yoshitane, who was now firmly entrenched in Kyoto, was the only remaining claimant to the title, and many Shogunate loyalists deserted to him, weakening Sumitomo and strengthening Takakuni.

This stalemate did not mean peace, however, and constant, low-level fighting would continue throughout the region and the wider realm; what would later be called the Sengoku Jidai was already well underway, even if the area immediately around Kyoto was relatively quiet.

In 1517, the stalemate was broken when Miyoshi forces in support of Sumitomo invaded Awaji and used it as a springboard to threaten the mainland. Around this time, the Ouchi Clan, who had supported Takakuni and Yoshitane for the better part of 10 years, left the capital to deal with unrest in their home provinces, caused by the apparent resurgence of Sumitomo and the Miyoshi’s faction.

The departure of the Ouchi was a major blow to Takakuni, and over the next two years, he saw his position gradually chipped away, as forces defected to Sumitomo or simply abandoned the fight to deal with their own affairs. Finally, in early 1520, Shogun Yoshitane himself switched sides, throwing his support behind Sumitomo and forcing Takakuni to flee Kyoto.

Takakuni fled to Omi Province, but he wasn’t ready to roll over just yet. Gathering a force of his allies, he counter-attacked in May 1520 and retook the capital. This time, his victory was decisive; he forced the leader of the Miyoshi Clan to commit suicide and even managed to drive Sumitomo back into exile on Shikoku, where he died of illness shortly afterwards.

The following year, Takakuni exiled the fickle Yoshitane and installed Ashikaga Yoshiharu, the son of Yoshizumi, as Shogun, though he was just as much a puppet ruler as his father had been. Takakuni was appointed kanrei (deputy) for the new Shogun’s enthronement ceremony, but would resign the position immediately afterwards, proving to be the last man to hold the position, according to historical records.

It wouldn’t be until October 1524 that the last embers of Miyoshi resistance were stamped out on Shikoku, but even then, Takakuni was far from secure in his position. In 1526, he faced serious opposition from within his own clan and was defeated when he tried to march against them. In 1527, this combined force actually managed to drive Takakuni out of Kyoto, and an attempted counterattack was defeated at the Battle of Katsuragawa in March that year.

Takakuni, ever tenacious, refused to give up, despite being defeated in 1528 and again in 1530. Things finally came to a head for him in 1531, at the Battle of Tennoji, which is often called the Daimotsu Kuzure, which can be translated as “The Fall of the Big Shots” (lit. big names fall, or collapse).

Takakuni was defeated. He survived the battle but was captured shortly afterwards, supposedly whilst hiding in an indigo storage barrel at a dye shop, after which he was obliged to commit suicide. Several of his main supporters (the eponymous “Big Names”) suffered similar fates, and Takakuni’s faction disintegrated.

Takakuni’s body was likely still warm (and probably blue, given his hiding place) when the forces that had opposed him turned on each other. Members of the Hosokawa, Hatakeyama, and Miyoshi Clans all began fighting, and any hope of retaining a stable government in Kyoto was lost.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%B0%B8%E6%AD%A3%E3%81%AE%E9%8C%AF%E4%B9%B1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A4%A7%E7%89%A9%E5%B4%A9%E3%82%8C

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%A1%82%E5%B7%9D%E5%8E%9F%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E6%99%B4

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%AD%89%E6%8C%81%E9%99%A2%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%8A%A6%E5%B1%8B%E6%B2%B3%E5%8E%9F%E3%81%AE%E5%90%88%E6%88%A6

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%88%B9%E5%B2%A1%E5%B1%B1%E5%90%88%E6%88%A6

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%8B%E7%94%B0%E4%B8%AD%E5%9F%8E

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E6%BE%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A4%A7%E5%86%85%E7%BE%A9%E8%88%88