“The enemy is at Honnoji” – Akechi Mitsuhide

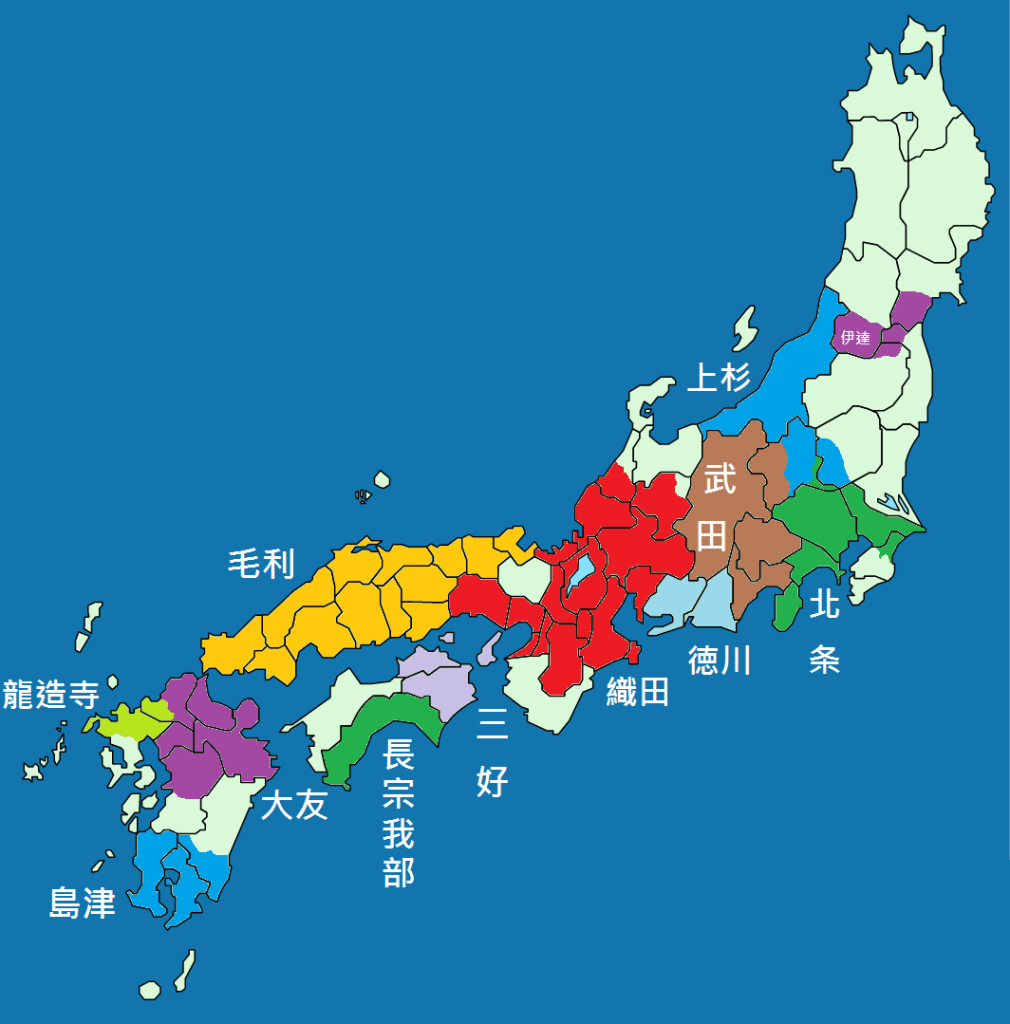

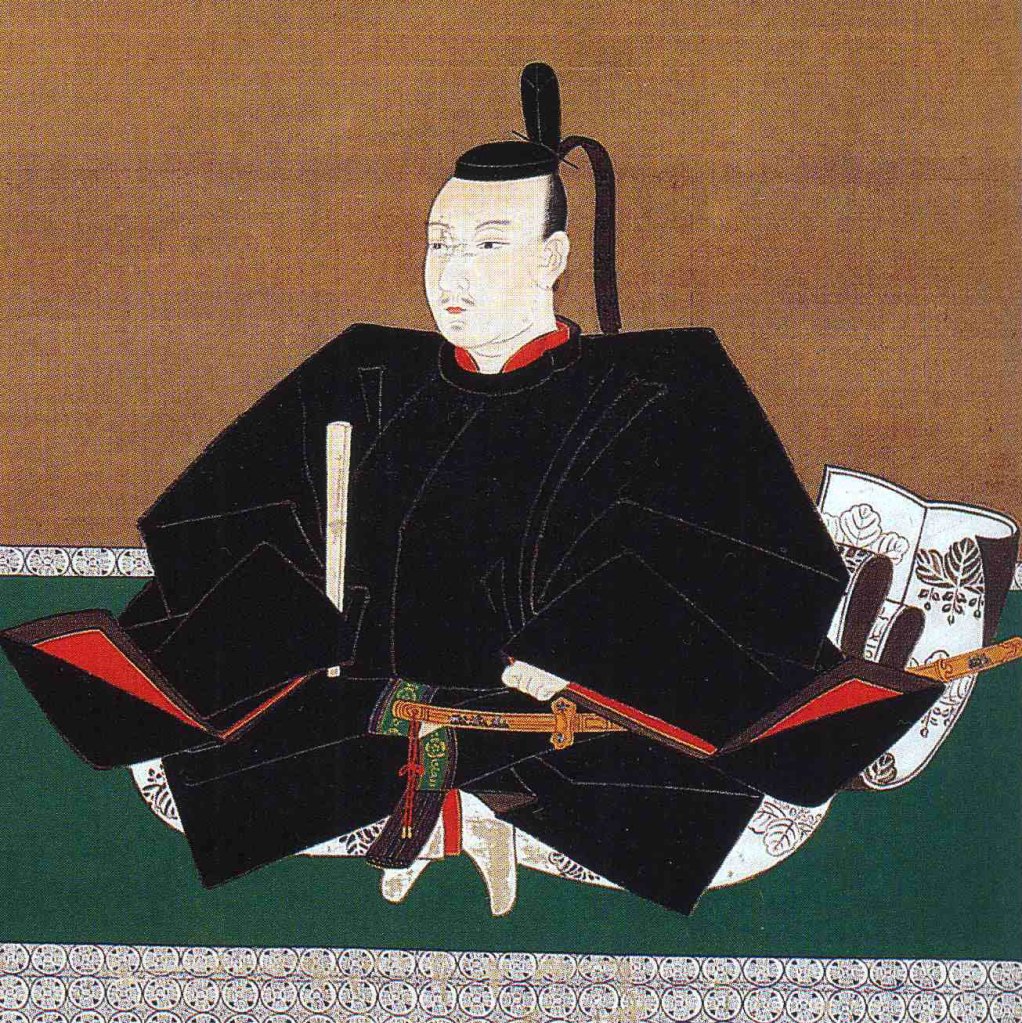

By 1582, Oda Nobunaga was the most powerful man in the realm; in fact, it could be argued that he was the most powerful man Japan had seen in centuries. A combination of ruthless political manoeuvring and brutal military campaigns had left him on the verge of finally reuniting the nation and ending the Sengoku Jidai.

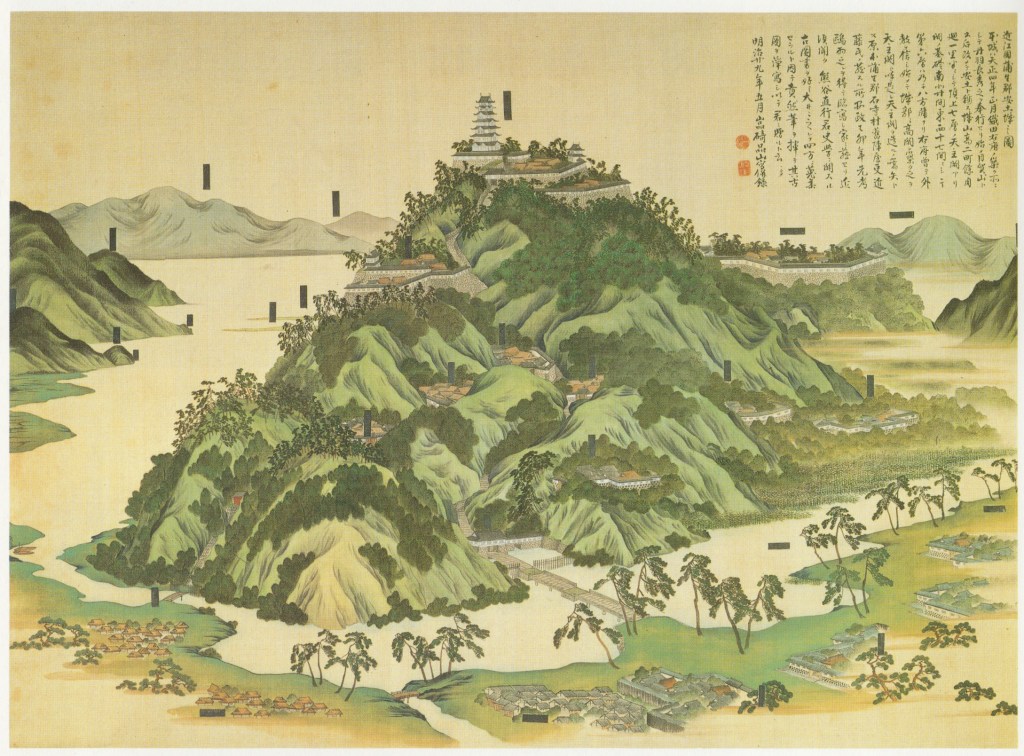

Only the Mori Clan still had the strength to stifle Nobunaga’s ambitions, and in May 1582, he announced his intention to march against them with all his might. The catalyst for this next campaign was a message from Hashiba Hideyoshi, who was besieging Takamatsu Castle (in modern-day Okayama). The message read that Mori Terumoto was marching to relieve the siege, presenting Nobunaga with an opportunity to meet the Mori in open battle and crush them.

It is generally accepted by historians that Nobunaga intended not only to defeat the Mori but also subjugate Shikoku and, eventually, Kyushu as well, viewing the campaign against the Mori as part of a wider strategy to bring the entire nation under his command. In preparation for this, he dispatched several generals to support Hideyoshi, most notably Akechi Mitsuhide.

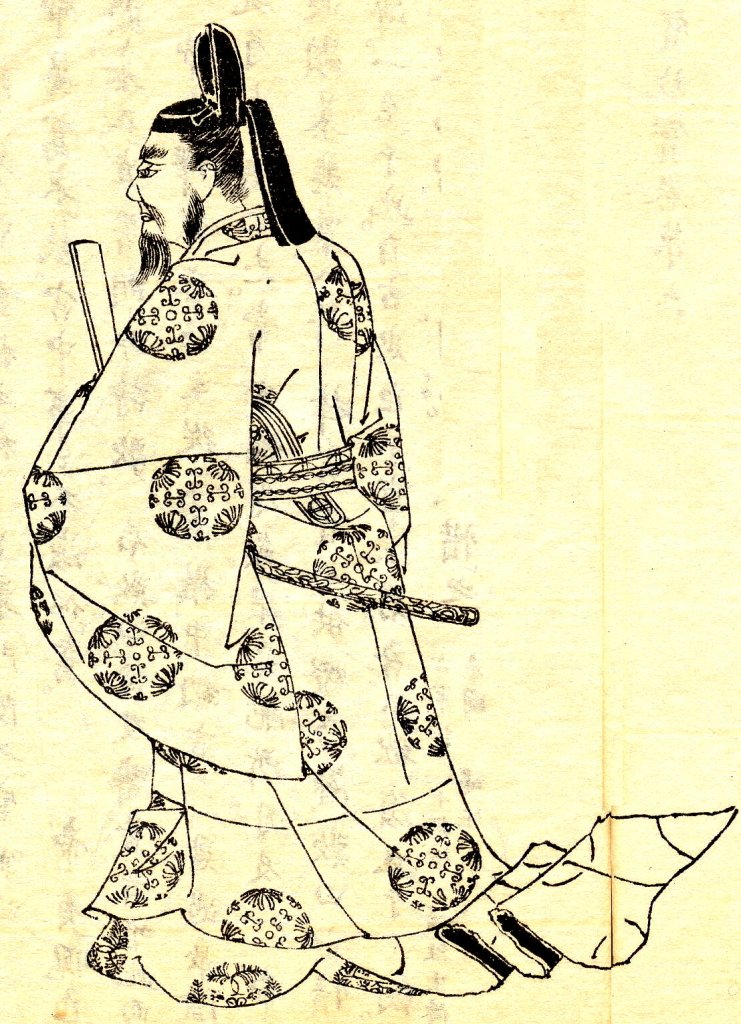

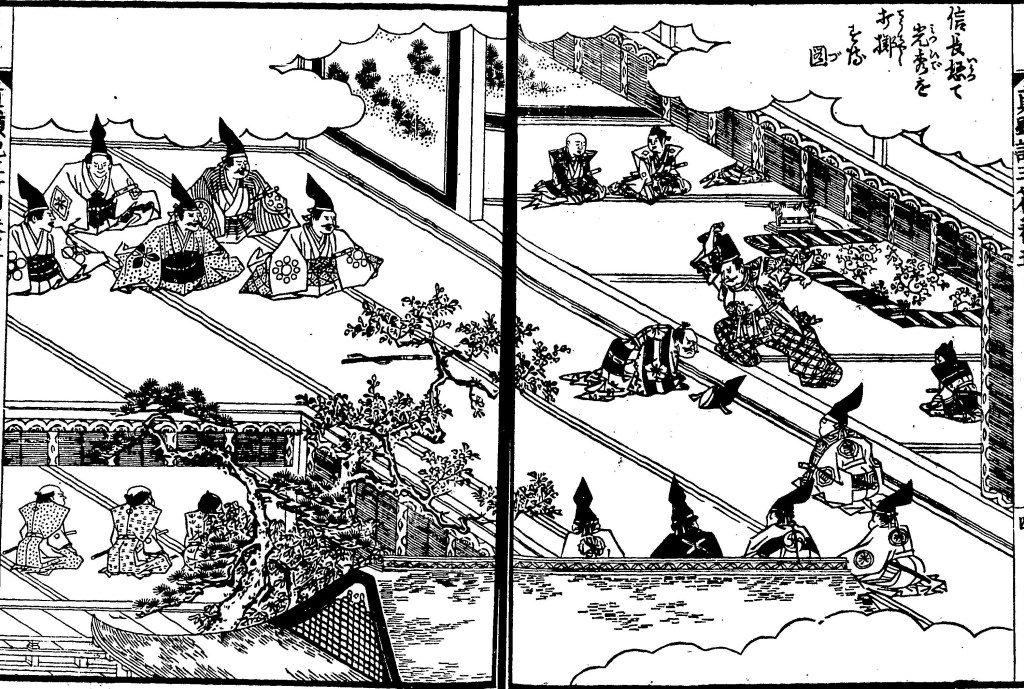

In the days that followed, Nobunaga was seen to be in good spirits and laid on lavish entertainment for those who came to visit him, including Tokugawa Ieyasu, who departed Azuchi on June 21st, embarking on a tour of Kyoto, Osaka, and the surrounding region. On the same day, Nobunaga’s son and heir, Nobutada, arrived in Kyoto for reasons that aren’t entirely clear (some speculate he meant to accompany Ieyasu). Whatever his purpose, his arrival in the capital meant that when Nobunaga himself departed Azuchi for Kyoto on June 29th, father and son would be in the same place, at the same time.

Exactly why Nobunaga went to Kyoto first is debated, with some suggesting he planned to attack Shikoku first, going via Kyoto and the port at Sakai (modern Osaka). Other sources say he went to deal with negotiations at the Imperial Court, and others still suggest he wanted to show off a new tea set he had recently acquired. (This may sound a touch comical to a modern audience, but the tea ceremony was a serious matter in Japan at the time.)

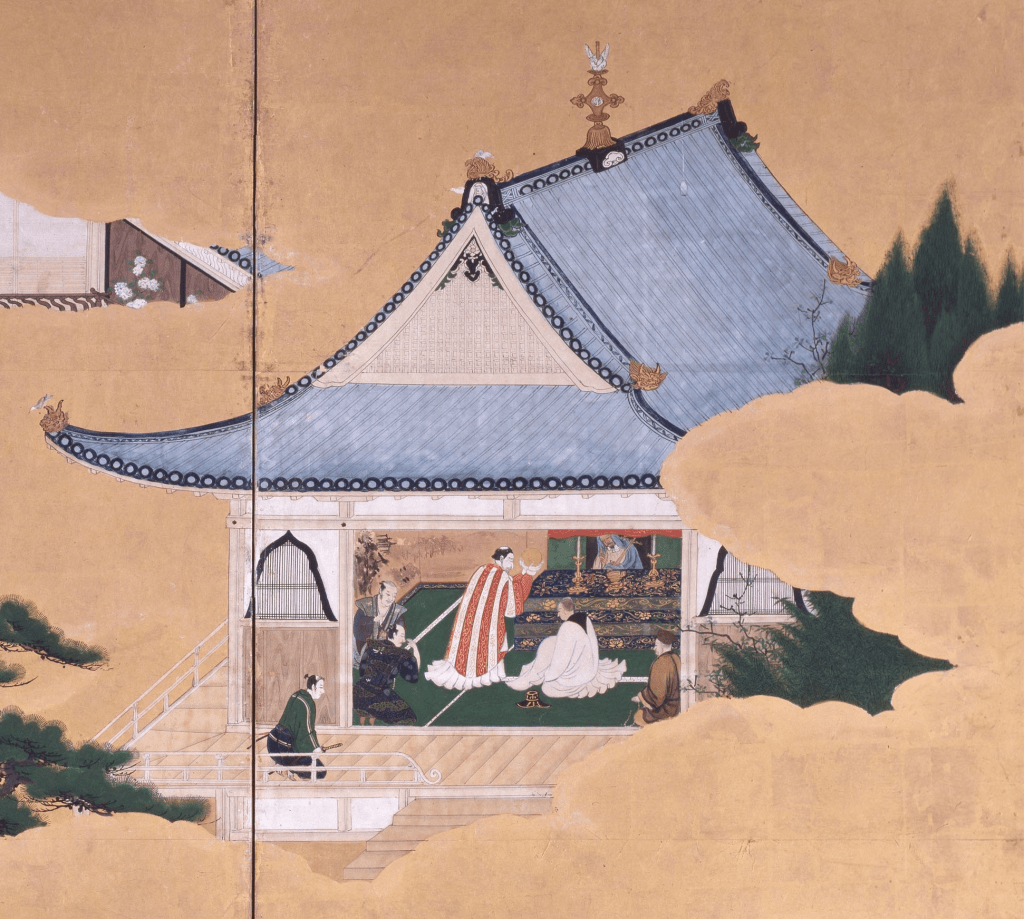

On June 30th, Nobunaga held said tea ceremony, which was followed by a drinking party, during which Nobunaga’s son, Nobutada, arrived, and father and son drank and talked together, little knowing that it would be their last meeting. Sources tell us that the party ended late, and Nobutada returned to his accommodation at nearby Myokakuji Temple, and Nobunaga retired for the night shortly afterwards.

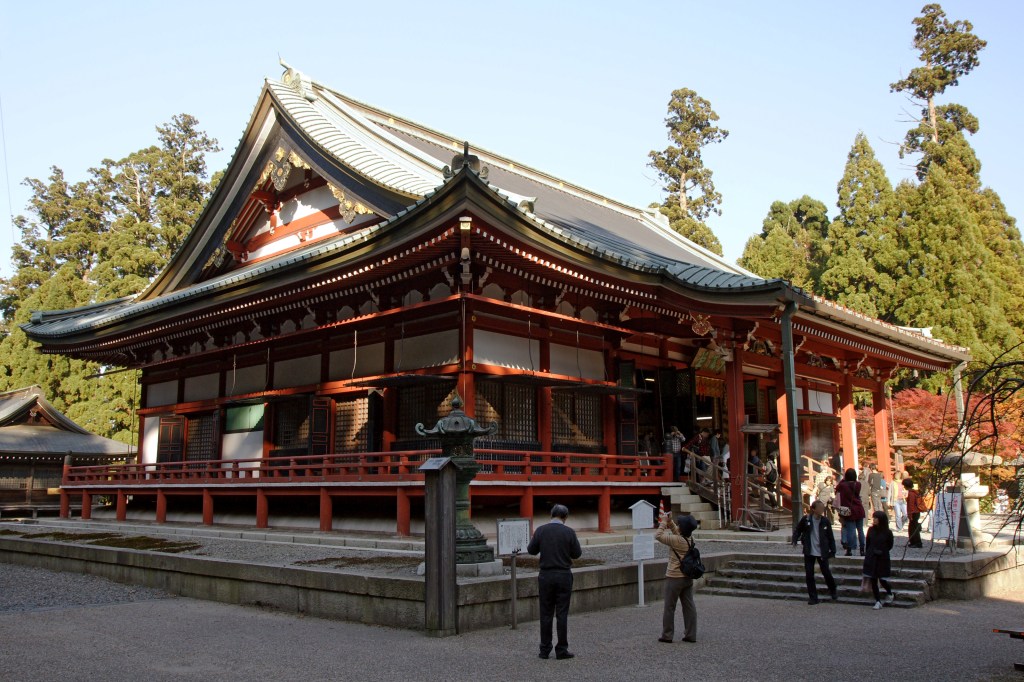

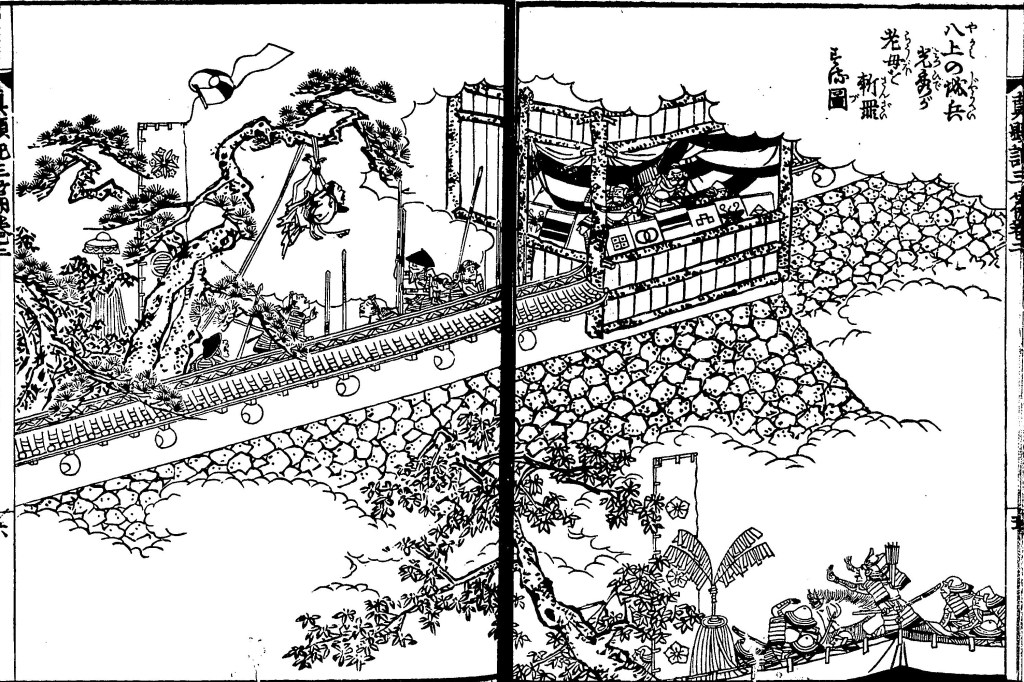

Though Honnoji was a temple, as the primary residence of Nobunaga in Kyoto, it wasn’t undefended. Excavations in 2007 found evidence of a moat and some earthworks, suggesting that the site had been partially fortified, though it was far from a fortress, and Nobunaga was protected by only a few dozen servants and his personal entourage.

Nobunaga clearly didn’t expect to be attacked, and why should he have? He was the most powerful man in the realm, in the heart of the capital city, with hundreds of thousands of warriors at his command. His enemies were far away, and even in the unlikely event that the army under Hideyoshi was defeated, he could call on other, just as formidable forces.

+- – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=107655314による

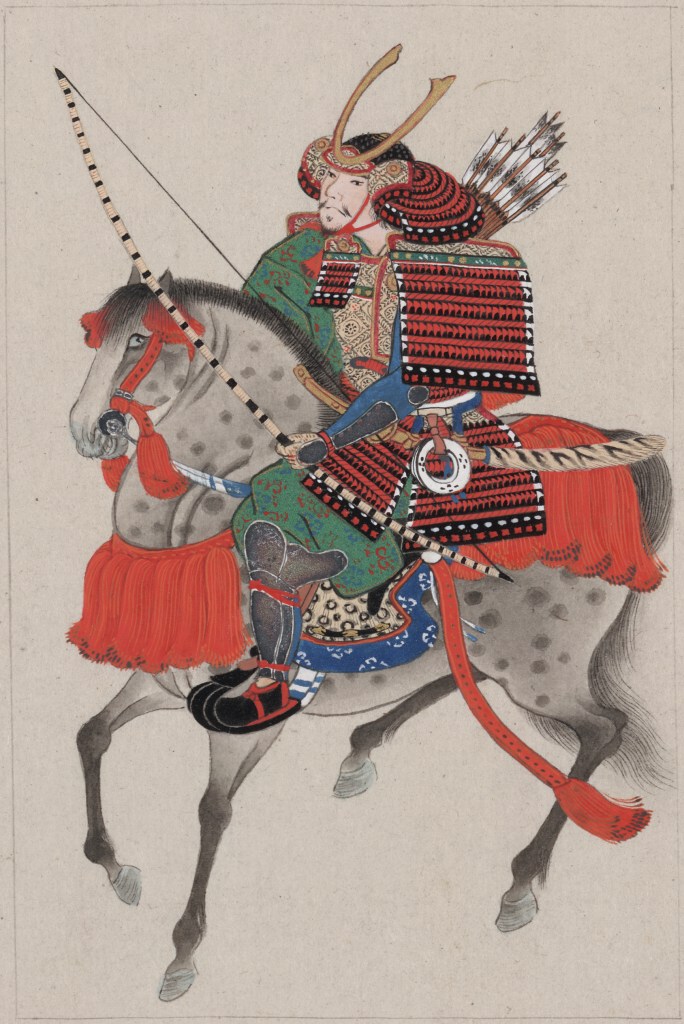

One of these was a force of around 13,000 men under Akechi Mitsuhide. In the afternoon of June 30th, Mitsuhide claimed to have received a message from Nobunaga, instructing him to bring his force to Kyoto for review. The letter, if it existed at all, was certainly a forgery, but by that evening, Mitsuhide had arrived at Kameyama (modern Kameoka), north of Kyoto. By the next morning, they had reached the Katsura River, and at this point, it is unclear if Mitsuhide’s army understood their objective.

Sources from men serving in this force suggest they believed that they were going to attack Tokugawa Ieyasu, nominally on the orders of Nobunaga himself. This is supported by the semi-contemporary “History of Japan”, written by the Jesuit, Luis Frois, which suggests that Mitsuhide’s army believed they were acting under Nobunaga’s secret order, at least initially.

At this point, Mitsuhide is supposed to have uttered the famous phrase “The Enemy is a Honnoji” announcing his rebellious intention (as everyone knew that was Nobunaga’s base.) Unfortunately, as dramatic as that scene might have been, the first source for it doesn’t appear until 1641, nearly 60 years after the event, and there are no contemporary sources that tell us what Mitsuhide might or might not have said.

What we know is that by dawn, Mitsuhides forces had surrounded Honnoji. What followed was a bloody, but ultimately one-sided fight. All sides agree that Nobunaga and his pages fought bravely, but they were hopelessly outnumbered, and the fighting was over by around 8am. We don’t know exactly how Nobunaga died, but the sources agree that he fought with a bow, and then a spear, before suffering some kind of injury (the sources differ) and retreating into the already burning Honnoji, where he presumably committed seppuku.

Nobunaga’s son, Nobutada, had, upon hearing that Honnoji was under attack, rushed to help, only to be overwhelmed and forced back to his own accommodations at Myokakuji Temple, where he too was forced to commit seppuku as the temple burned around him, his body consumed by the flames.

Rumours of their survival sprang up almost immediately. Since neither body was ever identified (this being before DNA or dental records), Mitsuhide could not prove the deed was done, and any hope he had of securing support went up in the same smoke that Nobunaga and his son had.

Whatever his actual motivation (which we’ll look at in a moment), Mitsuhide’s triumph would be short-lived. Though his forces had successfully killed Nobunaga, his son, Nobutada, and most of his inner circle, and secured Kyoto, the same forces that Nobunaga might have called on to defend him were now focused on avenging him.

Mitsuhide swiftly withdrew to Azuchi Castle, from where he tried to rally support, and wrote to the Imperial Court, seeking to legitimise his position. There are no records of any response, and he soon ran out of time. Hashiba Hideyoshi had made peace with the Mori (who were apparently initially unaware of Nobunaga’s death) and was now marching against him.

Mitsuhide was outnumbered two or three to one, and at the Battle of Yamazaki on July 12th, he was decisively defeated. Although losses were similar on both sides (about 3000), Mitsuhide’s army suffered from serious morale problems and disintegrated as the battle went against them, leaving Mitsuhide with just 700 warriors at day’s end.

Mitsuhide himself survived the battle, but he was either killed in the aftermath (possibly by bandits or opportunistic peasants) or else committed suicide due to injuries sustained on the battlefield. Whatever his end, he was definitely dead by the time his head was displayed outside the burned remains of Honnoji Temple, on or around July 17th.

No sooner was Mitsuhide dead than questions were raised about why he had betrayed his lord. Though Samurai overthrowing their overlords was nothing new, Nobunaga was uncommonly powerful, and his death threatened to unravel the fragile peace he had secured, especially in light of Mitushide’s failure to secure support or legitimacy in its aftermath.

Contemporary scholars and modern historians continue to debate exactly why Mitsuhide betrayed Nobunaga. He was certainly mistreated and often humiliated, sometimes even being publicly beaten by Nobunaga himself, so simple revenge is a possible motive. Other sources suggest it was to avenge his mother, who had served as a hostage to secure a truce years earlier, only for Nobunaga to break it, resulting in the poor woman being executed.

If public humiliation and the death of his mother weren’t reason enough, some suggest it was pure ambition; Mitsuhide may simply have wanted the power for himself, and he certainly wouldn’t have been the first to try it. Indeed, some historians speculate that if he had been able to prove that Nobunaga was actually dead, he might have gained some support, and the outcome could have been different.

Others suggest that Mitsuhide was a partisan of the Shogun, or possibly the Imperial Court, and overthrew Nobunaga in order to restore one or the other to power, though these ideas only emerged in the 20th century, and there’s little contemporary information to go on.

There’s also the speculation that Mitsuhide was working with one of Nobunaga’s other vassals. Some historians argue that Hashiba Hideyoshi was able to turn his army against Mitsuhide very quickly, leading to speculation that he knew the attack was coming. Historians have never conclusively dismissed this, though it has been pointed out that only the fastest of Hideyoshi’s troops actually made it to the Battle of Yamazaki, meaning that the quick turnaround might not have been that quick after all.

Other theories blame the Imperial Court, or the Mori Clan, for conspiring against a man who had proven to be an existential threat, as well as the Buddhist Clergy, who had plenty of reason to want vengeance on Nobunaga.

Another possibility is the Jesuits, who are suggested to have feared that Nobunaga might move against them, though there’s little evidence that he intended to (as he valued foreign trade), and Hideyoshi, his ultimate successor, would prove to be a far greater threat to Christianity in Japan.

Ultimately, most of this speculation comes from later sources, and there’s no way to know what Mitsuhide intended, only that his plans fell apart before being decisively ended on the battlefield at Yamazaki.

Hashiba Hideyoshi’s victory did not mean he inherited Nobunaga’s power, however, and the power struggle that followed threatened to undo the Great Lord’s work, but that’s a story for another time.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%B9%94%E7%94%B0%E4%BF%A1%E9%95%B7

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%9C%AC%E8%83%BD%E5%AF%BA%E3%81%AE%E5%A4%89

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%95%B5%E3%81%AF%E6%9C%AC%E8%83%BD%E5%AF%BA%E3%81%AB%E3%81%82%E3%82%8A

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%A1%82%E5%B7%9D_(%E6%B7%80%E5%B7%9D%E6%B0%B4%E7%B3%BB)

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BA%80%E5%B2%A1%E5%B8%82

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%82%99%E4%B8%AD%E9%AB%98%E6%9D%BE%E5%9F%8E%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Honn%C5%8D-ji_Incident

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akechi_Mitsuhide

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B1%B1%E5%B4%8E%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%B9%94%E7%94%B0%E4%BF%A1%E5%BF%A0

If you are interested, the main source for this and the other posts on Oda Nobunaga is the 2011 translation of the Chronicle of Nobunaga, the Kindle version of which can be found here.