Last time, we looked at how the Chosokabe rose from barely holding a single castle to becoming effective masters of the whole of Shikoku. In 1582, it had looked like they were about to be invaded and (probably) conquered by Oda Nobunaga, but his sudden death at the Honnoji Incident in June 1582 granted the Chosokabe a brief reprieve.

百楽兎 – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9987939による

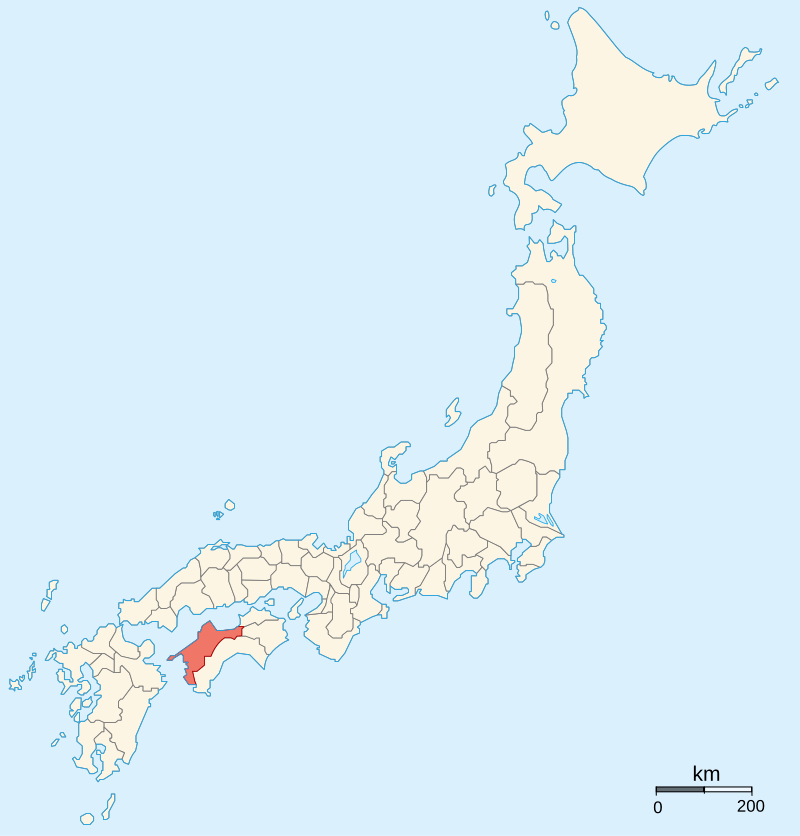

Between 1582 and 1585, they completed their conquest of Shikoku, although exactly how much control they really exerted is still debated by historians, with some suggesting that Shikoku was conquered and pacified, but others making the case that Chosokabe control outside of Tosa Province was tenuous.

Regardless of the nature of Chosokabe’s control of Shikoku, it would prove to be brief. In the spring of 1585, Hashiba Hideyoshi, fresh from defeating the last of his rivals to the mantle of Nobunaga’s successor, turned his attention to Shikoku. Hideyoshi ordered the Chosokabe to hand over Iyo and Sanuki Provinces, effectively ceding the northern half of Shikoku to him.

The Lord of the Chosokabe, Motochika, tried to negotiate, offering just Iyo Province. Hideyoshi was not a man to be bargained with, however, and in response to what he saw as Chosokabe’s defiance, he dispatched an army of some 100,000 men under the overall command of his brother, Hidenaga.

Shikoku was attacked from three sides: Sanuki and Awa by Hidenaga’s army, and Iyo by the Mori who had recently submitted to Hideyoshi and were keen for a chance to prove their loyalty. Attacked on multiple fronts and facing overwhelming numbers, the Chosokabe did not resist for long. At the end of July, after already having lost Awa Province, Motochika surrendered.

The terms were harsh, but not as bad as they might have been. Hideyoshi allowed the Chosokabe to keep control of Tosa Province, but the other three were divided amongst Hideyoshi’s vassals. In 1586, the Chosokabe would join Hideyoshi’s invasion of Kyushu, and though the campaign itself would be successful, Motochika’s heir, Nobuchika, was killed in battle.

Overcome with grief, Motochika is supposed to have tried to kill himself, only being dissuaded at the last minute by his vassals. Not long after this, he relocated the base of the clan to what is now Kochi Castle, and in 1588, he named his fourth son, Morichika, as the new heir.

By Taisyo – photo taken by Taisyo, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2157936

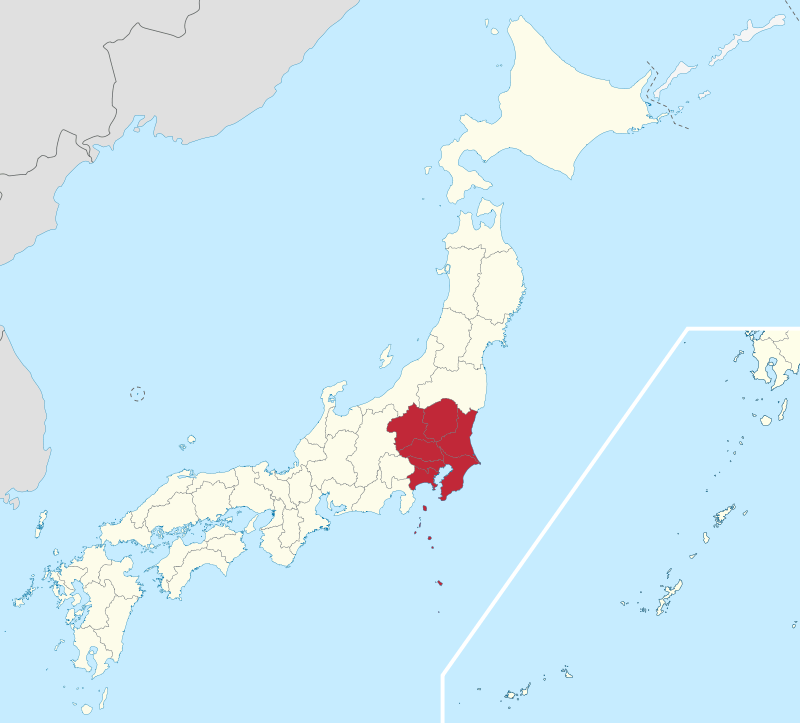

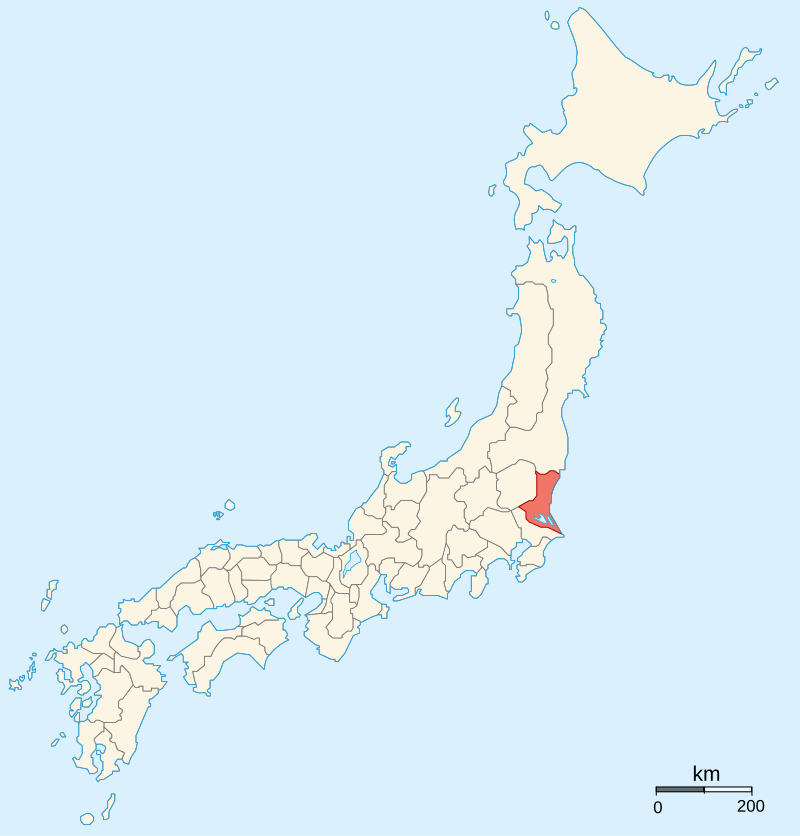

In 1590, the Chosokabe again went to war in the service of Hideyoshi, this time dispatching naval forces to attack the Hojo Castle at Shimoda with 10,000 men. The garrison of 500 held out for nearly two months, but it was eventually taken, and with it, the Chosokabe contribution to the wider Odawara Campaign came to an end.

In 1591, Motochika moved his base from Kochi Castle to a position at Urado (still within the modern city of Kochi). Some sources say this was because of the unfavourable location of the first castle (it was prone to flooding), whilst others suggest it was a strategic move, with Urado serving as the main base of the Chosokabe Navy, which took part in Hideyoshi’s long and ultimately unsuccessful invasions of Korea from 1592-1598.

In 1596, the San Felipe Incident occurred when a Spanish Galleon (the San Felipe, hence the name) was shipwrecked off the coast of Tosa and brought into the harbour at Urado. We’ll focus on this incident specifically in a later post, but the short version is that Motochika confiscated the remaining cargo of the Galleon, and when officials from Hideyoshi arrived in Kochi to take possession of the goods, the captain of the Galleon heavily implied that the presence of Christians in Japan was the precursor to a Spanish Invasion, explaining that that was how the Spanish had managed to conquer such a large part of the globe.

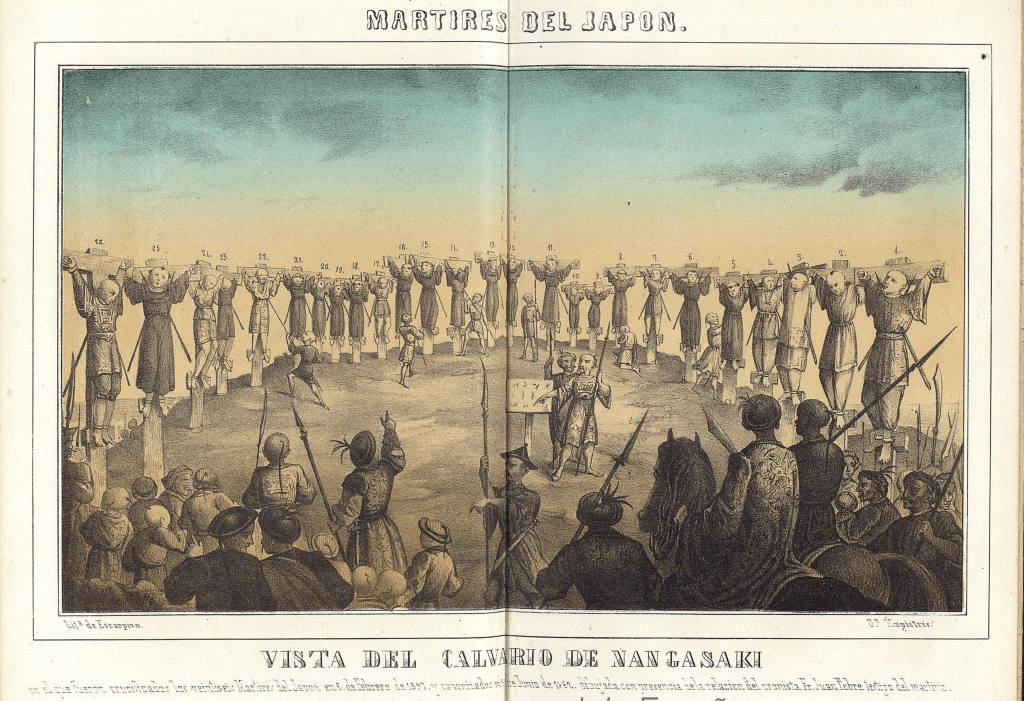

Hideyoshi had initially issued orders expelling Christian priests from Japan in 1586, but it had been unenforced before now. When news of the supposed Spanish invasion reached him, Hideyoshi was horrified, and in 1597, he had 26 Christians (including one passenger from the San Felipe) marched from Kyoto to Nagasaki (the centre of Christianity in Japan) and had all 26 crucified on a hill overlooking the city.

Motochika’s role in the persecution that followed is not clear, though Christianity had never been particularly strong on Shikoku, as the Chosokabe were largely opposed to foreigners in Japan, so it’s not hard to imagine he would have had no qualms about expelling them from his territory, even if he was not actively involved in the wider campaign.

Hideyoshi’s death in 1598 would threaten the fragile peace he had forged, as his son and heir was just a boy, and a council of five regents was appointed to rule in his stead. Though Motochika was not a member of the council, he was still a man of influence, and in 1599, he was in Kyoto for an audience with Toyotomi Hideyori (Hideyoshi’s son) when he fell seriously ill.

When it became clear that he wasn’t going to get better, he made his will, leaving control of the Chosokabe to his son Morichika, before he passed away in May that year. Morichika’s accession was far from smooth; he was unpopular amongst some of the Chosokabe’s retainers (apparently due to his arrogance and short temper), and the Toyotomi, de facto masters of Japan, didn’t recognise him as the new head of the clan.

Morichika would try to make good on his appointment by joining the Western Army (the pro-Toyotomi side) at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600. This would prove to be an unwise choice in the end, as the Western Army was defeated by the Eastern Army under Tokugawa Ieyasu. Although the Chosokabe had not actually been involved in the final battle, they had chosen a side and would not escape the consequences.

Morichika was punished by having Tosa taken from him. Though there would be some protest, the decision proved to be final, and the Chosokabe’s time as feudal lords was over. Motochika would campaign to have his territory restored until around 1605. In 1610, he supposedly became a monk, and although his movements around this time are unclear, by 1612, he was under direct surveillance from the new Tokugawa Shogunate.

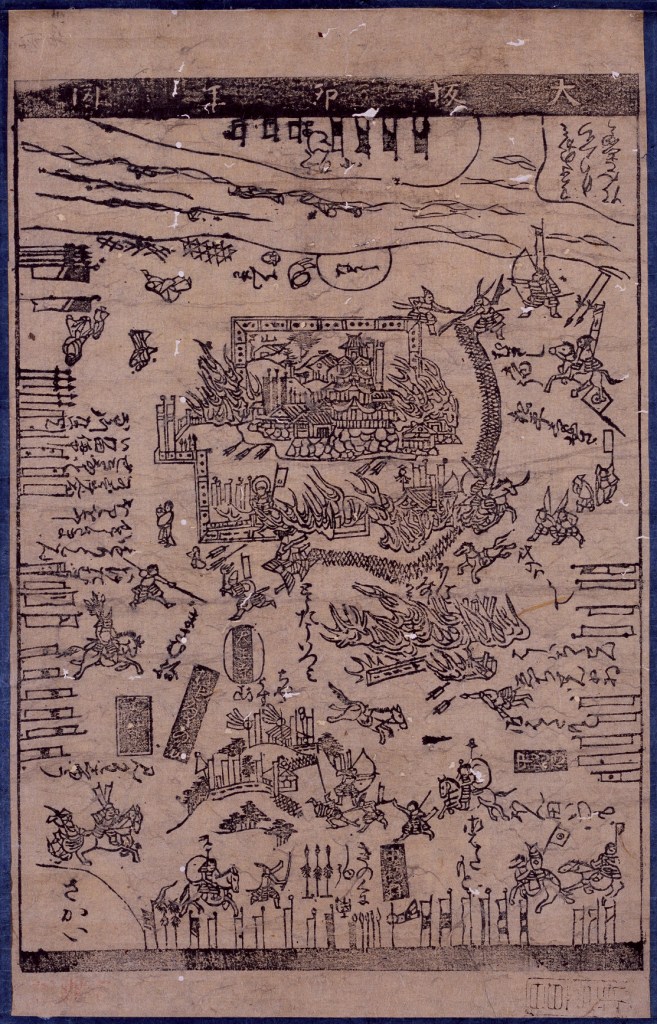

The new Shogun was right to suspect him, as, during the Osaka Campaign in 1615, he sided with the Toyotomi, hoping to secure the restoration of Chosokabe lands in Tosa. In the event, the Tokugawa would be victorious in that campaign, snuffing out the last of the Toyotomi Clan, and securing their rule.

Morichika is reported to have fought bravely, leading an attack on the Tokugawa’s main camp that was ultimately unsuccessful, but which managed to inflict serious casualties on the Tokugawa army before being forced to withdraw. With Osaka Castle eventually falling to the Tokugawa, Morichika initially fled, but he was discovered and then humiliated by being paraded around Kyoto before being beheaded.

Morichika’s death brought an end to the Chosokabe. Some sources state he had as many as five sons, all of whom died premature and violent deaths. Some other sources, however, suggest that he had just two children, a girl and a boy, one who married a local retainer, and the other who was whisked away after the Siege of Osaka and raised elsewhere. Unfortunately, in both cases, reliable sources are hard to come by, and the truth appears to be that the Chosokabe died with Morichika.

The Chosokabe name would be revived in later years by descendants of Motochika’s brother, Chikafusa, who had been adopted into the Shima Clan years earlier and thus survived the end of the Chosokabe. The family survived in this form until March 2025, when the last head of the family, Chosokabe Tomochika, passed away childless, aged 82.

「今は個人の時代。家を背負う時代ではありません。逆にこれからの世代が、自分の思いで新しい歴史を作っていくのも立派なことじゃないかと思いますね」

“We are now in the age of the individual. It is no longer the age to shoulder the burden of a family. On the contrary, I think it is admirable for future generations to create a new history based on their own ideas.” – Chosokabe Tomochika

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%95%B7%E5%AE%97%E6%88%91%E9%83%A8%E7%9B%9B%E8%A6%AA

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%85%AD%E6%9D%A1%E6%B2%B3%E5%8E%9F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%95%B7%E5%AE%97%E6%88%91%E9%83%A8%E5%85%83%E8%A6%AA

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ch%C5%8Dsokabe_Morichika

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%82%B5%E3%83%B3%EF%BC%9D%E3%83%95%E3%82%A7%E3%83%AA%E3%83%9A%E5%8F%B7%E4%BA%8B%E4%BB%B6

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%8B%E7%94%B0%E5%9F%8E_(%E4%BC%8A%E8%B1%86%E5%9B%BD)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Felipe_incident_(1596)

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%95%B7%E5%AE%97%E6%88%91%E9%83%A8%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%95%B7%E5%AE%97%E6%88%91%E9%83%A8%E5%8F%8B%E8%A6%AA

https://croissant-online.jp/life/54209/