Just a quick note: Date is pronounced “Da-Tay”.

Like many of the great clans of the Sengoku period, the Date’s exact origins are subject to a fair amount of mythologising. The family originally claimed to be descended from the prestigious Fujiwara Clan, but that doesn’t have very much supporting evidence, and most modern scholars agree that the clan’s origins were far more humble.

That isn’t to say they didn’t earn their place, however. The first attested ancestor of the Clan was Date Tomomune, who was rewarded for services in battle with the manor of Date in modern Fukushima Prefecture. Tomomune himself is a bit of a murky figure (as they all seem to be), and there are still unanswered questions about his origins and even his identity, but for the sake of simplicity, we’ll agree with the Date’s own genealogy and start the story of the clan with him.

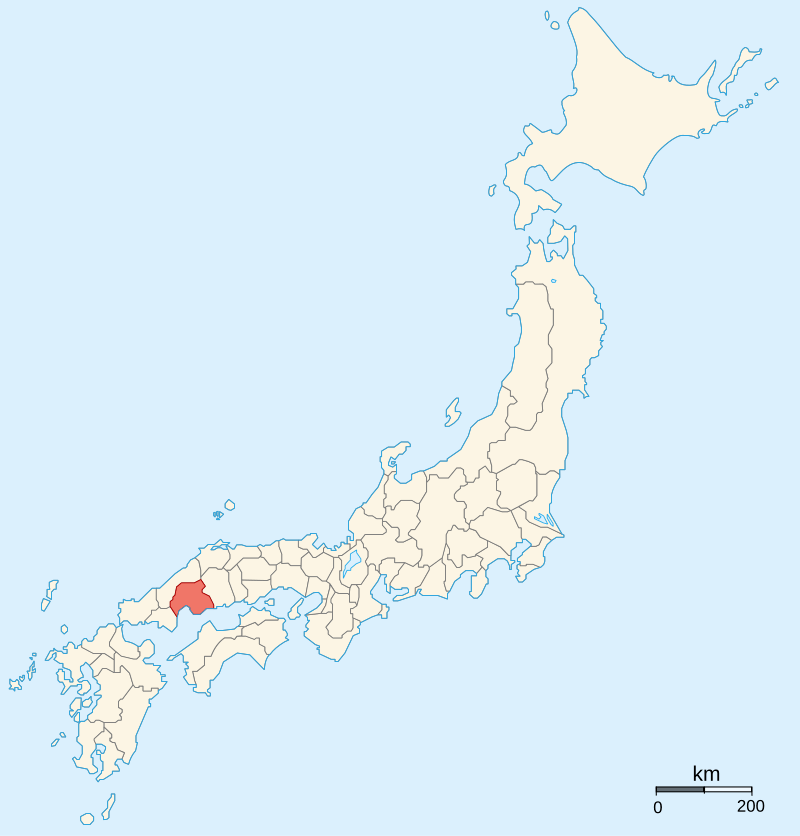

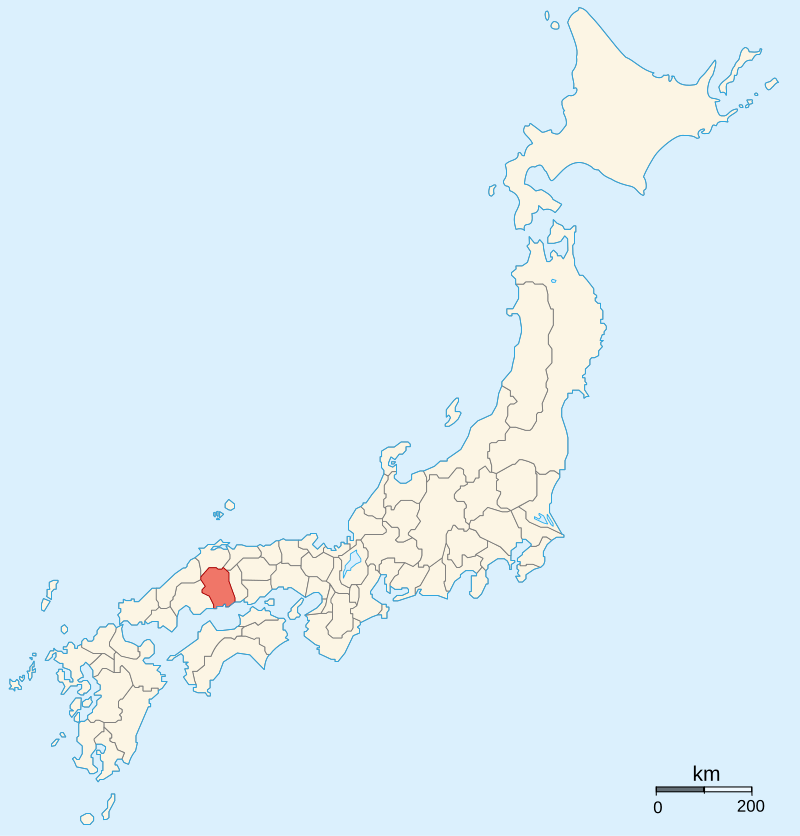

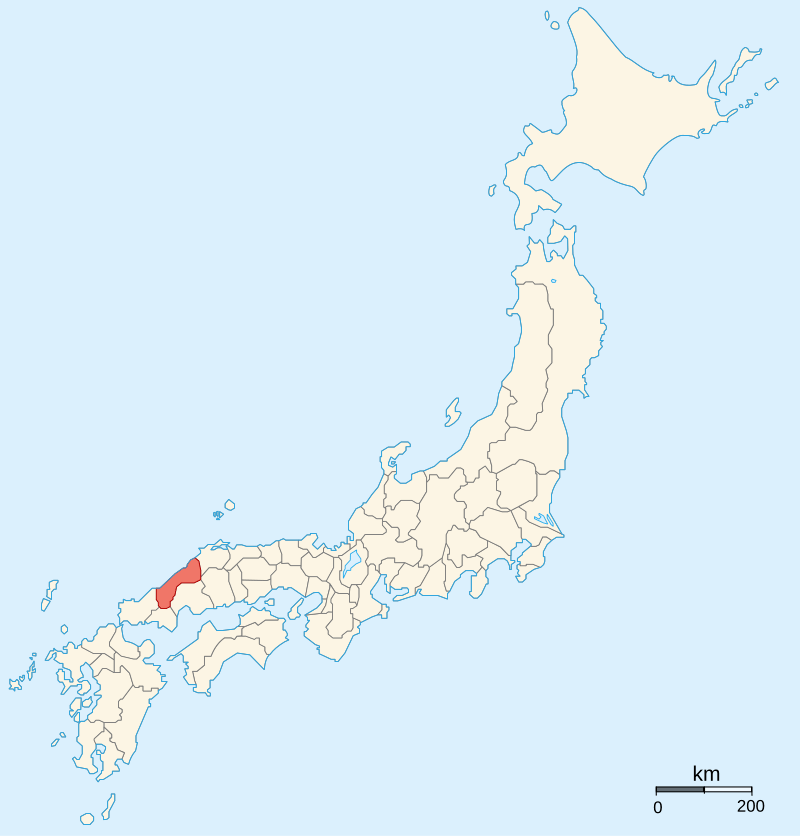

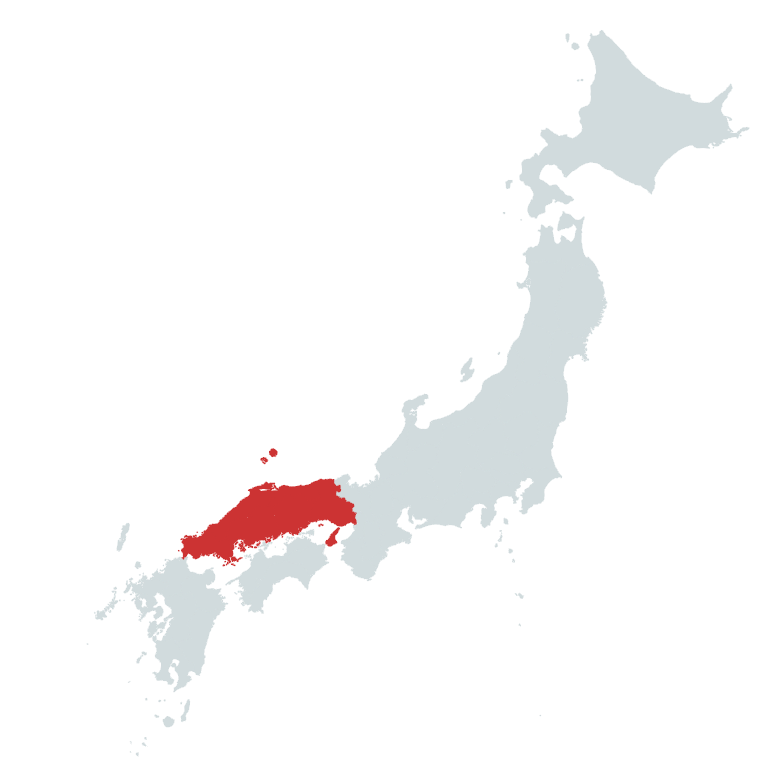

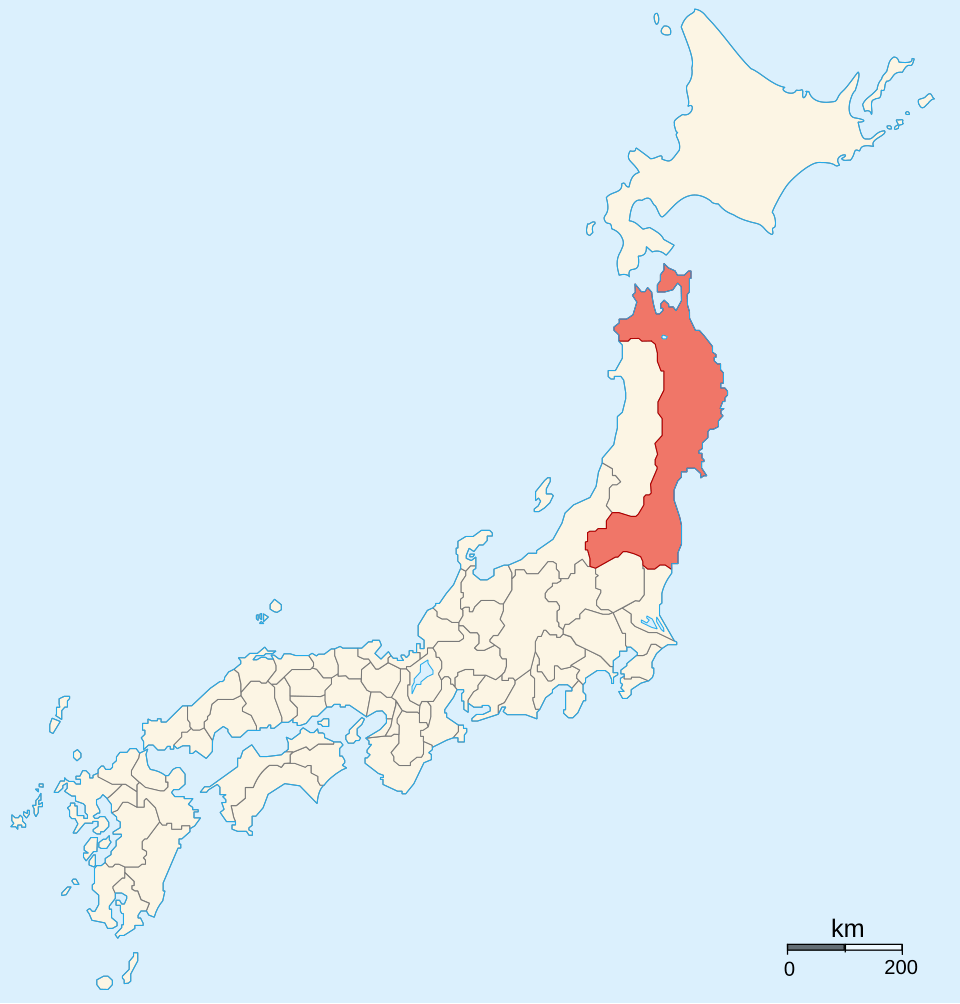

Similar to many other clans in the period, the Date were not tied down to a single geographic location, and branches of the clan would pop up all over Japan as their fortunes rose and fell. For our purposes, it is the Date clan of Mutsu Province that we’ll be focusing on.

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image: Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1690724

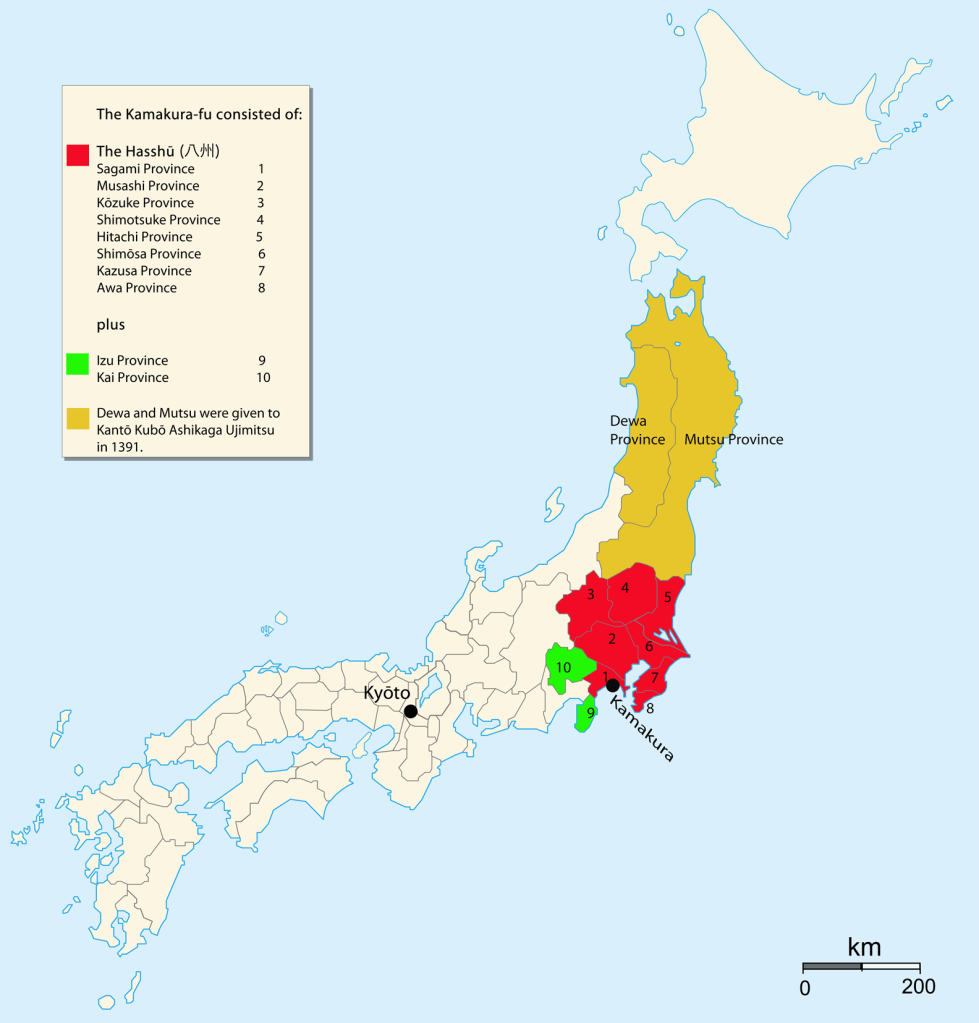

The Date largely supported the Kamakura Shogunate, founded by Minamoto no Yoritomo, and in the 13th century, the Lord of the Date is said to have been living in Kamakura (the political capital). However, when the Shogunate was overthrown, the Date threw in their lot with the Emperor and would continue to support the Imperial throne even after the establishment of the Ashikaga Shogunate in 1336.

This support would backfire, however, as the Date, in support of the Southern Court, were defeated by forces of the Northern Court, loyal to the new Ashikaga Shoguns, and ultimately obliged to switch sides. Beginning in the 1380s, the Date would set about restoring their strength by attacking rival clans in their home region. As was common at the time, these local conflicts were framed as part of the larger Northern-Southern Conflict (the Nanboku-cho Period), but were, in reality, private wars that the central authorities were powerless to direct.

Later, when the power of the Ashikaga Shoguns was beginning to fracture, the Date would use the conflict between the government in Kyoto and the Kamakura kubo to further enhance their own power. Though nominally under the jurisdiction of Kamakura, the Date would appeal directly to Kyoto to serve as their vassals. The Shogunate agreed, and when open conflict between Kyoto and Kamakura broke out in the 1480s, the Date were in a prime position to take advantage.

An example of how strong the Date had become can be found in records from 1483, in which the Lord of the Date dispatched gifts to the court in Kyoto, including 23 swords, 95 horses, 380 ryo of gold dust, and 57,000 coins. This was an extraordinary fortune at the time, and seems to have led to the acceptance by the court of the Date’s position of the strongest (or at least richest) clan in the North.

Despite their wealth and power, the Date were not the most prestigious clan in the region. That honour went to the Osaki, who were faithful to the Shogunate in Kyoto and were long established. As was common during the later 15th century, however, the Osaki had a prestigious name, but their actual power was crumbling. Though nominally their subordinates, the Date would intervene in a power struggle within the Osaki Clan in 1488, bringing an end to the conflict, but effectively reducing the Osaki to vassal status in the process.

Another rival to the Date was the Mogami Clan from neighbouring Dewa Province. The clans would clash repeatedly, but in 1514, Date Tanemune would inflict a decisive defeat on the Mogami at Hasedo Castle. Shortly after this, he would marry his sister to the defeated Lord of the Mogami, effectively binding the two clans together. This would prove unpopular with the remaining Mogami vassals, and when their Lord died in 1520, and the Date attempted to take direct control, they rebelled.

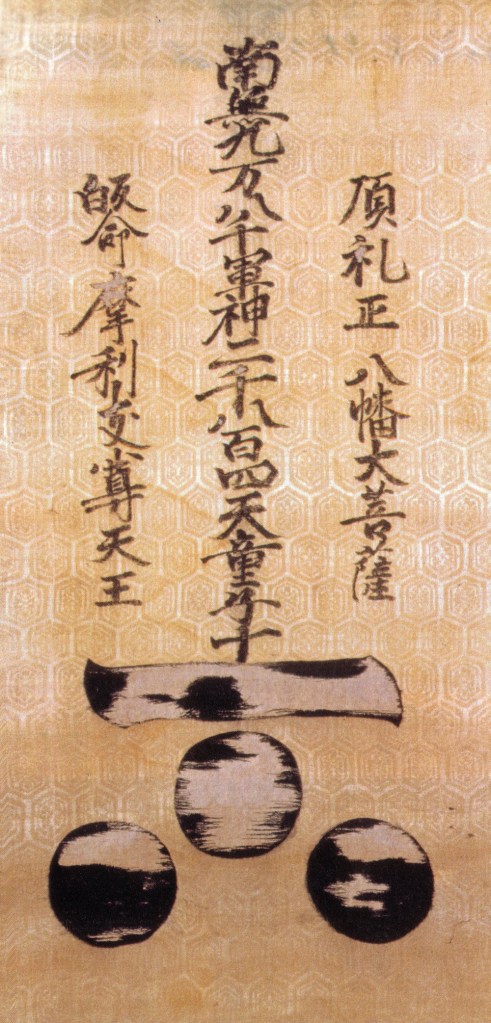

Koda6029 – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=124663430による

In defeating the rebellion, Tanemune was able to establish Date control over most of eastern Dewa Province, further expanding his clan’s power and prestige. In recognition of this, in 1522, the Shogunate appointed Tanemune shugo (governor) of Mutsu Province (the Date’s home province, remember). Tanemune was not satisfied, however, as he had apparently sought the title of tandai.

The exact distinction between shugo and tandai is a little unclear, as the titles often overlapped, but essentially, a shugo was the governor of a single province, whereas a tandai was the Shogun’s representative over a wider area. Although the power and prestige of the Shogunate were at a low ebb by this point, the fact remained that tandai was a more prestigious title, and the Shogunate’s refusal to bestow it on Tanemune was seen as a proverbial slap to the face.

Tanemune responded to this but charting his own course, although the snub is probably just a convenient excuse for what he was going to do anyway; by the early 16th century, Shogunate power was really more of a concept, and the Date were one of many powerful clans who realised that they could largely do as they pleased.

Over the next 20 years, Tanemune would work to consolidate his clan’s control over the North, further absorbing the Osaki and Mogami clans, as well as extending physical control over most of Mutsu and Dewa Provinces. Despite his successes, all was not well within the clan; Tanemune was in conflict with his eldest son, Harumune. The exact nature of the conflict is complicated, but it got so bad that in June 1542, Harumune ambushed his father whilst the latter was out hunting, imprisoning him in a nearby castle from which Tanemune swiftly escaped (or was rescued, depending on the source)

What followed was a six-year conflict which saw the Date severely weakened, and several of their recently conquered vassals breaking free, including the Osaki and the Mogami. Eventually, the mediation of the Shogun brought about an official peace, but in reality, the feud didn’t end, and although Harumune would take his place as the de facto head of the clan, Tanemune, despite becoming a monk, remained an enormously influential figure.

Harumune’s reign would be occupied with reestablishing Date power. The situation was far from ideal, however, and he was eventually forced to confirm many of the concessions that had been granted to vassals by both sides, signing away territory and privileges in exchange for obedience.

One upside for Harumune was the fact that he had no fewer than eleven children, six sons and five daughters, who would be useful pawns in returning former vassals to the fold. All of his daughters were married either to powerful clans, securing alliances, or to senior vassals, ensuring their loyalty, and by the 1560s, the Date’s position was once again strong.

In 1565, Harumune retired and handed control to his son, Terumune, although, as was common, he retained all the actual power. A year later, the Ashina Clan attacked the Nikaido, who were allied with the Date through the marriage of one of Harumune’s daughters. The Date intervened but were defeated, and when the Nikaido surrendered shortly afterwards, peace between the Date and Ashina was secured through another marriage, this time between the Lord of the Ashina’s eldest son and Harumune’s fourth daughter.

Harumune apparently opposed this marriage, and in response, Terumune entered into a secret agreement with the Ashina, in which they would agree to support him in the event of an outbreak of conflict between father and son. The feud between father and son would only be resolved in 1570, when Terumune removed several retainers who had facilitated Harumune’s rule from ‘behind the curtain’. With this, the relationship seems to have improved, as Harumune was now effectively powerless anyway.

Like most of his contemporaries, Terumune’s reign would be dominated by war, but we’ll talk about that next time.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mutsu_Province

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%9C%80%E4%B8%8A%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E7%A8%99%E5%AE%97

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E6%88%90%E5%AE%97

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A4%A7%E5%B4%8E%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E5%B0%9A%E5%AE%97

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E5%AE%97%E9%81%A0

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E9%83%A1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B8%B8%E9%99%B8%E5%85%A5%E9%81%93%E5%BF%B5%E8%A5%BF

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E6%9C%9D%E5%AE%97

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dewa_Province

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E6%99%B4%E5%AE%97

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E8%BC%9D%E5%AE%97