We’ve spent a lot of time talking about the breakdown of Shogunate power during the 15th Century. We’ve also discussed the three most powerful clans that were located closest to Kyoto during the Onin War. The Hosokawa, Yamana, and Hatakeyama Clans all played leading roles in the fighting, and in the aftermath, all three were seriously weakened.

But what about the provinces? We’ve only spoken in very broad terms about what was going on out there, mostly because, to focus on it would require posts that resemble small novels, and keeping track of all those names and places is a task that is beyond most of us.

In the interests of keeping things moving, then, I have generally neglected to go into much detail; however, since we’re now at the beginning of the Sengoku Jidai, a period of civil war lasting 120 years, we need to take a moment to look at who the main players are now that the Onin War is over.

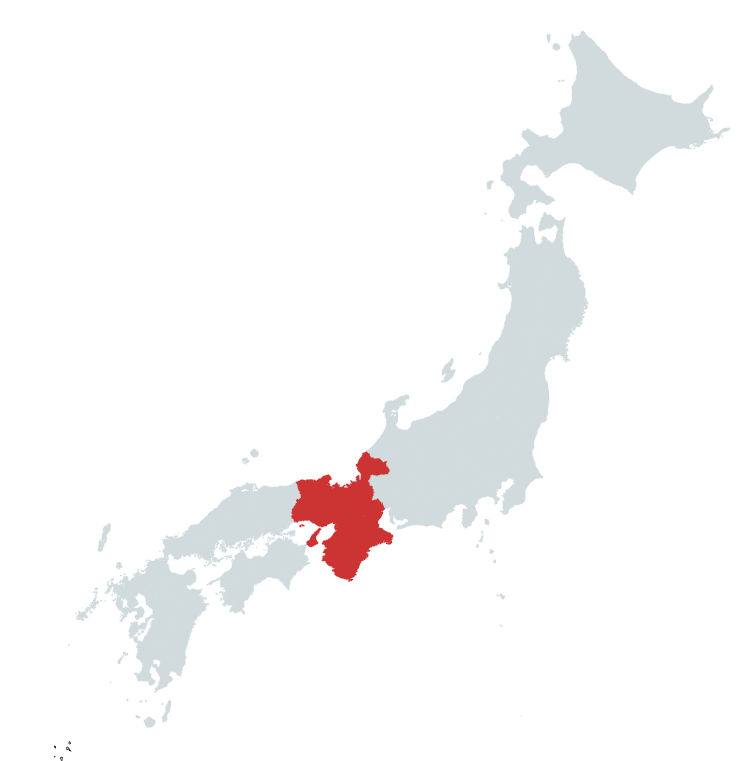

Central Japan

We’ve spent a lot of time looking at this region recently, so this is just a quick overview of who is still on the field in this part of Japan.

The Hatakeyama Clan had been one of the main players, but a serious succession dispute fractured the clan and eventually led to the Onin War, as the Hosokawa and Yamana Clans supported rival claimants in a feud that would spiral out of control.

By the end of the 15th Century, the Hosokawa remained largely in control of Kyoto, but they were already in decline. They would remain powerful, but a succession dispute (yes, another one) would divide the clan in the early 16th Century, and they’d never recover.

The Yamana Clan had been badly mauled by the Onin War, and from a position as one of Japan’s mightiest clans, they’d eventually lose everything but a single province, which they’d manage to hold until the end of the 16th century, when some poor political decisions would see them forfeit even that.

The Hatakeyama, for their part, were fragmented repeatedly throughout the late 15th Century, and they’d never recover their former power. However, some descendants would hold positions of power in Kyoto until the 1580s, when they’d run afoul of Oda Nobunaga, a name you should remember.

Eastern Japan

The power in Eastern Japan was centred mostly around the Kanto Plain, with the political capital at Kamakura. In the period preceding the Ashikaga Shogunate, Kamakura had been the de facto capital of Japan, and even after the new Shogunate relocated to Kyoto, Kamakura remained the regional capital, and holding it was a prize in itself.

The Kanto region was the source of a lot of trouble for the Ashikaga Shoguns, as there was the legacy of the previous Shogunate to contend with, and the strong, often semi-independent Kamakura Kubo to contend with. The kubo was the head of the local government, and they often openly defied the Shogun, who had to rely on the fickle loyalty of other powerful clans in the region to enforce his will.

The Uesugi

By Mukai – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8629467

The dominant power in the Kanto in the 15th Century was arguably the Uesugi Clan. Like many others, the clan claimed descent from the illustrious Fujiwara Clan, and various members of the family would become shugo in and around the Kanto. Their most important role, however, was that of Kanto Kanrei, the Shogun’s deputy in the Kanto, a position that was supposed to complement that of the kubo, but in reality, often served as a check on Kamakura’s power, and frequently, a direct rival.

Like most clans at this time, the Uesugi were divided into branches, three in this case, that were just as likely to fight as support each other. This infighting predated the Onin War, but the outbreak of general civil war saw the destruction of one branch, and the serious weakening of the other two, so much so that, in the early 16th Century, the Uesugi would lose their position in the Kanto to another rising power, the Hojo.

The Uesugi would survive, however, and continue to play a major role in the Sengoku Jidai. The clan’s most famous son is arguably Uesugi Kenshin, who would engage in a rivalry with fellow warlord Takeda Shingen that became the stuff of legend. Mythology aside, Kenshin would die without heirs, and a succession crisis would severely weaken the clan.

Although they would survive, they chose the losing side in the final battles of the Sengoku Jidai and would end up in Yonezawa Domain, in modern Yamagata Prefecture, where they would actually prosper until the abolition of the Domains in the 19th Century.

The clan endured into the modern day. The current head is Uesugi Kuninori, who was a professor at the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science until he retired in 2006.

The Hojo

By Mukai – No machine-readable source provided. Own work assumed (based on copyright claims)., CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9416600

The Hojo Clan, or more accurately the Go-Hojo, or Later Hojo, were relative latecomers to the scene. Although they would lay claim to illustrious ancestry (which was the style at the time), their progenitor was Ise Sozui (better known as Hojo Soun), who, despite being revered as the ancestor of the clan, never used the name Hojo himself. Traditionally, Soun was believed to have been a Ronin (masterless samurai) who rose to power seemingly out of nowhere in the aftermath of the Onin War.

More recent scholarship, however, seems to indicate that Soun’s family, the Ise Clan, had a much longer history and would serve in the Shogun’s government in Kyoto before relocating to the Kanto later.

Soun arguably deserves a post of his own, but the short version is that, he was originally in the service of the Imagawa Clan, another power in the region, before raising an army of his own and taking Izu Province for himself, establishing his base at Odawara Castle, which he took in 1494, some say, after tricking the previous owners, convincing them to leave on a hunting trip, and arranging their murders.

It was his son, Ujitsuna, who renamed the clan to Hojo. You may remember that it was the Hojo Clan who acted as regents for the Kamakura Shoguns, rising to such power that they were effectively masters of Japan, before being overthrown by the Ashikaga.

This new Hojo Clan was no relation to these regents, hence why they are referred to as the “Later” Hojo. Ujitsuna, apparently attempting to add some prestige to his family, adopted the name and mon (family crest) of the former Hojo, and everyone just went with it.

Ujitsuna wasn’t just savvy with brand recognition, however. Throughout the first half of the 16th century, he would guide the Hojo to become the predominant power in the Kanto. He would challenge and eventually drive out the Uesugi, taking control of their castle at Edo, which would eventually become the Imperial Palace in modern Tokyo.

Throughout the Sengoku Period, the Hojo would continue to be masters of the Kanto, eventually becoming one of the greatest powers in the late 16th century, before they were eventually defeated by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1590. A branch of the family would survive as the lord of Sayama Domain (near modern Osaka) until the 19th century, and members of this family would continue playing a role in Japanese politics into the 20th century.

The Takeda

The Takeda also claimed descent from the Minamoto Clan, and from the earliest days of the Kamakura Shogunate in the 12th Century, they had established their power base in Kai Province (modern day Yamanashi Prefecture). Though they were a relatively minor player (one amongst many, you might say), the Takeda would develop a difficult relationship with the Uesugi Clan.

When the Uesugi rose up against the Kamakura Kubo in 1416 (the Zenshu Rebellion), some members of the Takeda sided with the Uesugi, whilst others remained loyal to the government. The Uesugi were eventually defeated, but there was now bad blood between the Takeda and Uesugi that would last for another 120 years.

The best known Takeda was certainly Takeda Harunobu, better known to history as Takeda Shingen. He is widely regarded as one of the best leaders of the Sengoku Period; indeed, some scholars have speculated that, had it not been for his sudden death in 1573, we might now be talking about Shingen as one of the great unifiers of Japan.

Alas, it wasn’t to be. Shingen was succeeded by his far less capable son, Katsuyori, who would lead the Takeda to disaster at the Battle of Nagashino in 1575, and the clan would cease to have any meaningful power after a final campaign led by Oda Nobunaga in 1582.

Much like other major clans of the era, the Takeda Clan would live on in much reduced straits, eventually becoming direct vassals of the Tokugawa Shoguns, receiving a stipend of just 500 Koku a year. For reference, a Daimyo (great lord) could only claim that rank if he controlled lands worth 10,000 Koku a year or more. The Takeda had once controlled lands that were estimated to produce 1.2 million Koku, which gives you some idea of how far they had fallen.

The Rest

There are still several other regions to cover, and many more clans, but we’ll cover them next time.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%8A%E6%9D%89%E9%82%A6%E6%86%B2

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%8A%E6%9D%89%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8C%97%E6%9D%A1%E6%97%A9%E9%9B%B2

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H%C5%8Dj%C5%8D_S%C5%8Dun

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%BE%8C%E5%8C%97%E6%9D%A1%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AD%A6%E7%94%B0%E6%B0%8F