If you’ve been reading my blog for a while, you might be forgiven for thinking that Japanese history was mostly focused on the Kanto or Kansai regions (modern Tokyo and Kyoto/Osaka, respectively). Whilst the capital was in Kyoto, and some of the most powerful clans were based either there or in the Kanto, there were others, just as powerful and just as ambitious, who were based in other parts of Japan.

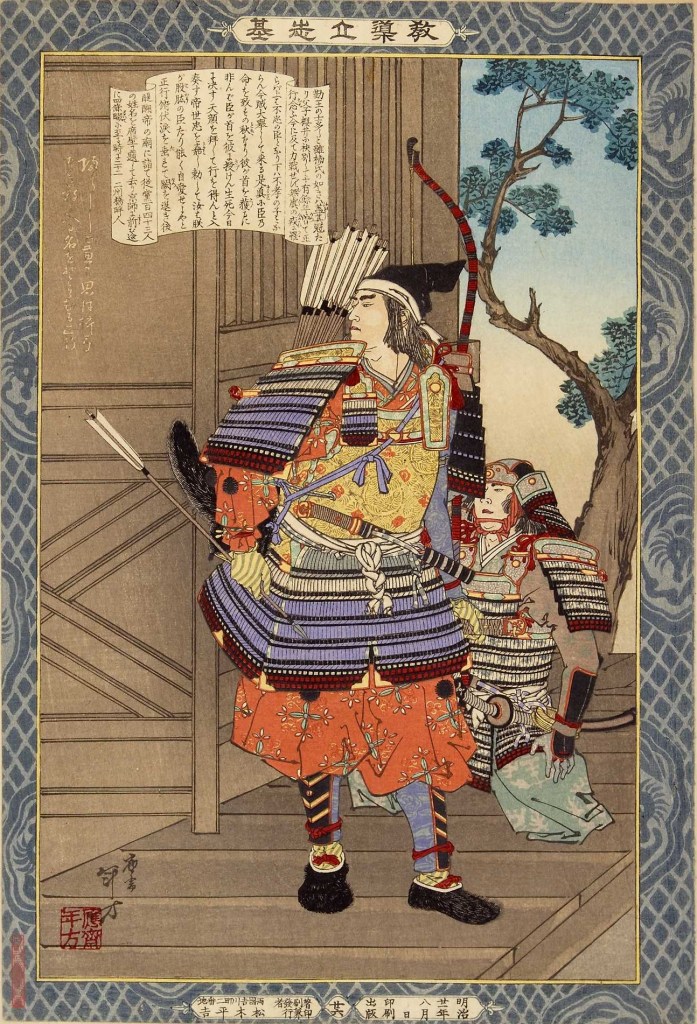

One such clan was the Mori, who we have mentioned briefly previously but are deserving of a much closer look. The subject of this post is Mori Motonari, and though he would go on to establish himself and his clan as one of Japan’s strongest, when he was born in 1497, there was little to indicate that the Mori would be anything other than a regional footnote.

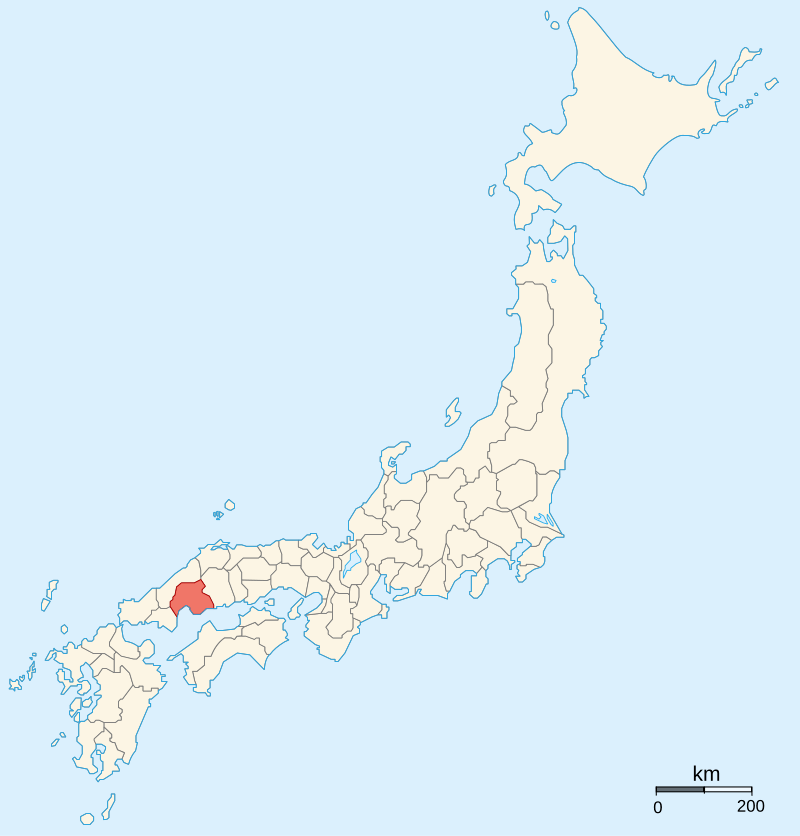

In the early 15th century, the most powerful clan in the region was the Ouchi, who played a significant role in the turmoil surrounding Kyoto and the Ashikaga Shogunate in the late 1400s. The Mori were based in Aki Province, in modern-day Hiroshima Prefecture, and found themselves caught up in the conflict between the Ouchi and the Hosokawa, who by this point were in effective control of the Shogunate.

In 1500, in a bid to avoid having to choose sides, Motonari’s father, Hiromoto, retired as head of the clan and was replaced by his son (Motonari’s older brother), Okimoto. Motonari would have a tough childhood, even by the standards of the day. His mother died in 1501, and his father in 1506, either from stress or alcohol poisoning (or a combination of the two).

In 1507, Okimoto had chosen his side, as he accompanied the Ouchi to Kyoto, leaving 10-year-old Motonari back in Aki. The young lad then had his income embezzled by unscrupulous vassals, leaving him destitute. However, the embezzler died suddenly in 1511, and Motonari’s income was restored.

Also in 1511, Okimoto returned from Kyoto and set about preserving the clan’s position in Aki Province. In 1513, Motonari would make a formal pledge of loyalty to his brother, supporting Okimoto’s rule, and (ideally) avoiding the kind of fratricidal violence that plagued so many of Japan’s other clans.

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1645417

In 1515, there was an outbreak of violence in Aki and neighbouring Bingo (yes, it was really called that) province. In response, the Ouchi dispatched a member of the Takeda Clan to restore order. (You may remember we spoke previously of several branches of the Takeda family, this one is sometimes called the Aki-Takeda, due to the location of their base.)

The Aki-Takeda proved to be unreliable vassals, however, as they took advantage of the chaos to rebel against the Ouchi and take control of several castles for themselves. Okimoto, continuing his service to the Ouchi, would attack the Aki-Takeda and take one of their castles, forcing them to withdraw and giving birth to a local rivalry that would be important for Motonari and the Mori Clan.

In 1516, Okimoto died suddenly, aged just 24, apparently also from alcohol poisoning. His son was just two years old, and so Motonari would become the guardian and acting head of the clan. A sudden change in leadership can leave a clan vulnerable, and the Aki-Takeda sought to take advantage, attacking several castles in Aki Province that protected the Mori heartlands.

Motonari was obliged to respond and proved his mettle several times in the war that followed. Between 1517 and 1522, Motonari would engage in a series of sieges and battles against the Aki-Takeda, which would see Mori gradually extend control across southern Aki province (in the area around modern Hiroshima), and even into neighbouring Bingo.

Despite his personal successes, the overall situation remained chaotic, and in 1523, the Amago Clan, seeking to expand their influence, advanced into Aki Province. Motonari, who had fought for the Ouchi up to that point, switched sides and aided the Amago in their conquests of several castles in the region.

This relationship would be relatively short-lived, however. In 1523, Okimoto’s son (Motonari’s nephew), who had been the nominal head of the clan, died, aged just 9. As was common, there was no clear successor, and although he had been the de facto head for years, Motonari was opposed by a faction that wanted his half-brother in charge instead.

Initially, Motonari was able to secure enough political support to be named head of the clan, and he was even recognised as such by the Amago. Almost as soon as the ink was dry, though, the Watanabe Clan, who had supported Motonari’s half-brother, began agitating against him.

The situation worsened when several other clans joined the conspiracy, apparently with the approval (or possibly even direct support) of the Amago Clan. Motonari’s position was still insecure, and he was forced to take action, launching a purge of those involved. Japanese politics at this time was usually an extremely bloody affair, and it wasn’t uncommon for entire families to be wiped out as punishment for rebellion.

Though Motonari ordered the death of his half-brother and his key supporters, he stopped there. No harm was done to the wives and children of the conspirators, as Motonari himself seemed to believe the incident was not so much a rebellion as it was interference from the Amago. Indeed, it was even suggested at the time that Motonari deeply regretted the killings, blaming himself for not having been able to stop the conspiracy, and the Amago for having encouraged it.

Quite why the Amago were so keen to conspire against Motonari isn’t clear, but they’d soon have cause to regret it. In 1525, as a response to Amago meddling, Motonari switched sides again, giving his support back to the Ouchi, who had largely stabilised their own situation by this point. Motonari would use this new alliance to expand his control of Aki Province even further, as many of the local clans remained loyal to the Amago and were now prime targets for Motonari’s revenge and political ambitions.

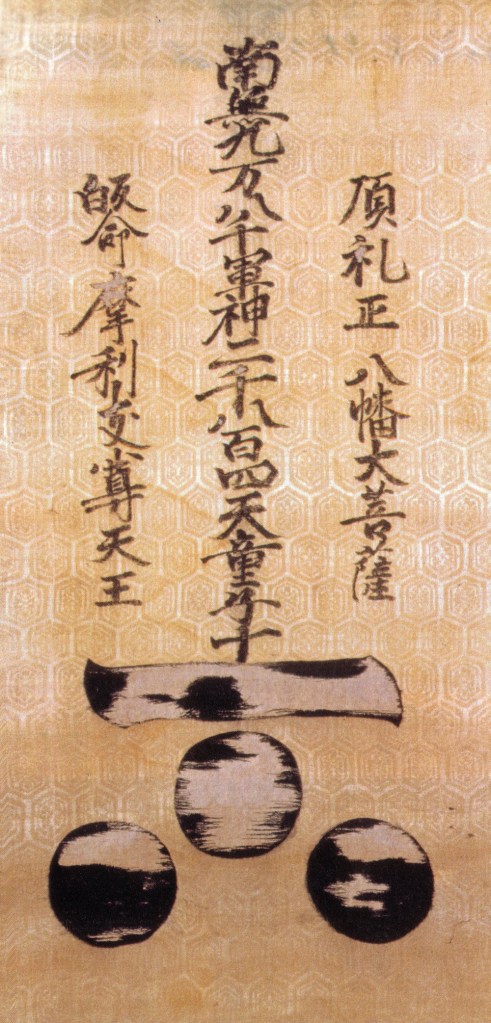

Over the next few years, Motonari would use a combination of diplomacy, threat, and outright force to establish broad control of Aki Province. In 1532, 32 local vassals of the clan signed a document pledging to follow Motonari’s lead and establishing him as the final arbiter in legal matters within the province. Also that year, Motonari was (with the support of the Ouchi) granted an Imperial title. As we’ve discussed previously, these titles were largely just for show by this point, but they did serve to increase Motonari’s personal prestige.

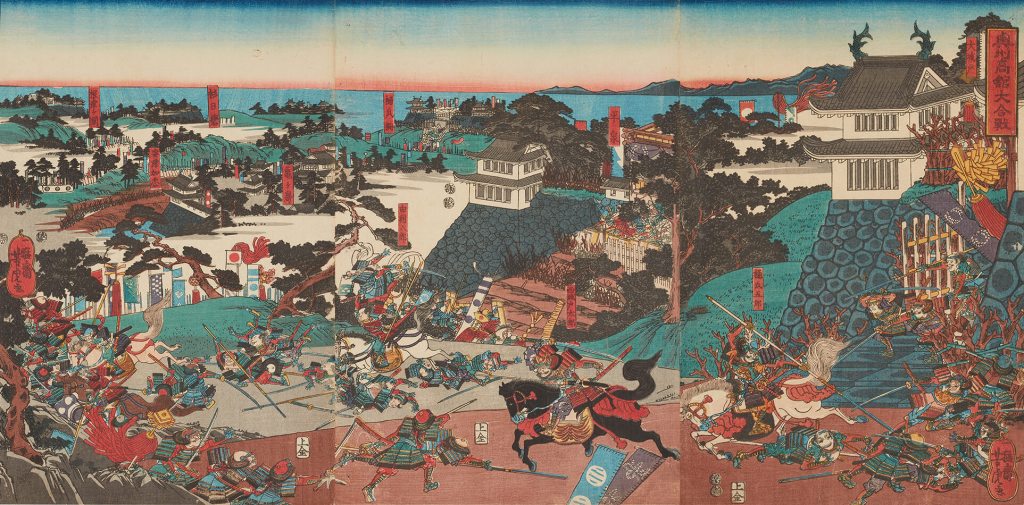

In 1540, the ongoing Amago-Ouchi war reached a new level of escalation, as the Amago marched into Aki Province with 30,000 men. Standing in their path was the Mori home castle at Yoshida-Koriyama, which quickly came under siege. Despite being outnumbered as much as 10 to 1, Motonari held out, and the Battle of Yoshida-Koriyama (which was actually a series of battles) eventually ended in the Mori’s favour, as the castled was relieved by Ouchi reinforcements, and the Amago were forced into a humilitating retreat, ending their attempts to conquer Aki, and leaving Mori control of the province in a much stronger position.

In 1545, Motonari’s wife died, and shortly after that, he announced his retirement as head of the clan. In a letter to his son, he strongly implied that it was grief over the passing of his wife that led him to make the decision. In 1546 (or possibly 1547), Motonari formally retired in favour of his son, Takamoto. However, as was common, Motonari’s ‘retirement’ was just for show, and he retained almost complete control of the clan.

As control over Aki and Bingo provinces was established, and Mori power increased, Motonari was now in a strong enough position to deal with his remaining internal enemies. In 1550, after gaining the tacit approval of the Ouchi (still the Mori’s nominal overlords), Motonari launched a violent purge of the Inoue Clan, one time vassals of the Mori, who had begun to operate independently, presenting a threat to Mori internal stability.

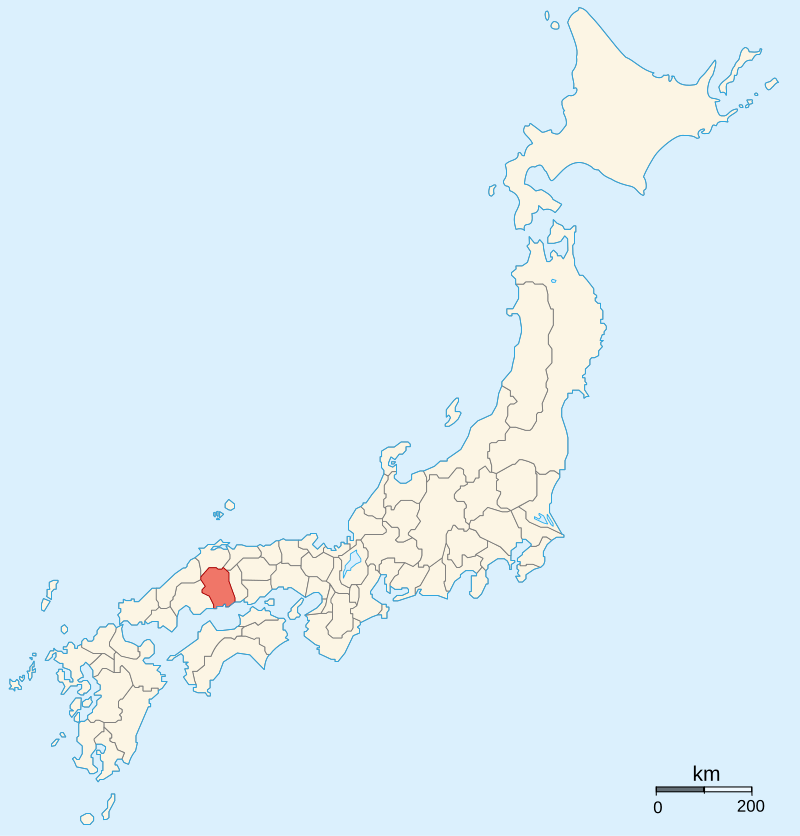

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1652300

What followed was the massacre of up to 30 individuals, which left the other Mori vassals fearing for their lives. However, Motonari gathered 238 of them and had them sign a pledge of loyalty and obedience. All agreed, and the end of the Inoue Clan further cemented Motonari’s position.

A year later, the Ouchi themselves fell victim to an internal coup, their leader was assassinated, and replaced by his son, though the real power would be with the new regent, Sue Harutaka (pronounced soo-eh, by the way). Motonari took advantage of the chaos to capture several castles that remained loyal to the old Ouchi Lord, and Harutaka agreed, recognising the Mori as lords of the Aki and Bingo provinces.

This rapprochement didn’t last long (they never do), with Harutaka soon regretting the power he had given Motonari, and he demanded that he return control. Motonari, unsurprisingly, refused, and shortly after that, conflict broke out. The problem for the Mori was one of numbers; Harutaka was regent of the Ouchi Clan, the regional power, and could muster 30,000 men, to the Mori’s 5000.

Fortunately for Motonari, the Ouchi were facing several rebellions in the aftermath of the coup, and their forces were divided. This gave the Mori their chance, and at the Battle of Oshikibata in 1554, the Mori, despite being outnumbered nearly 2 to 1, launched a surprise attack against the Ouchi and won.

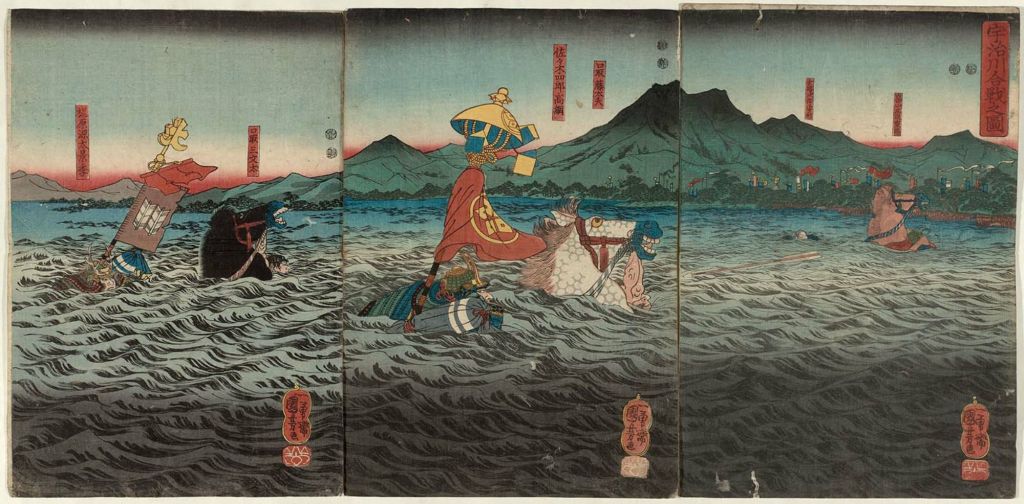

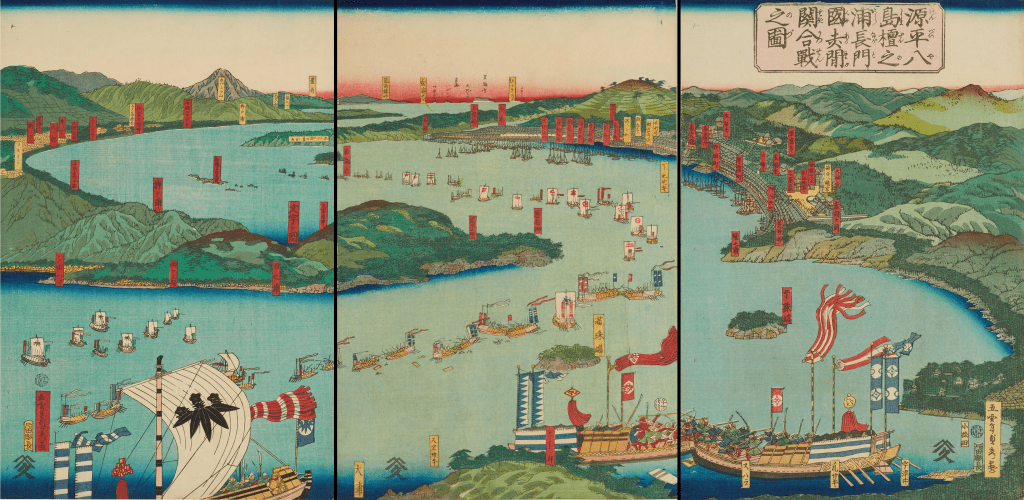

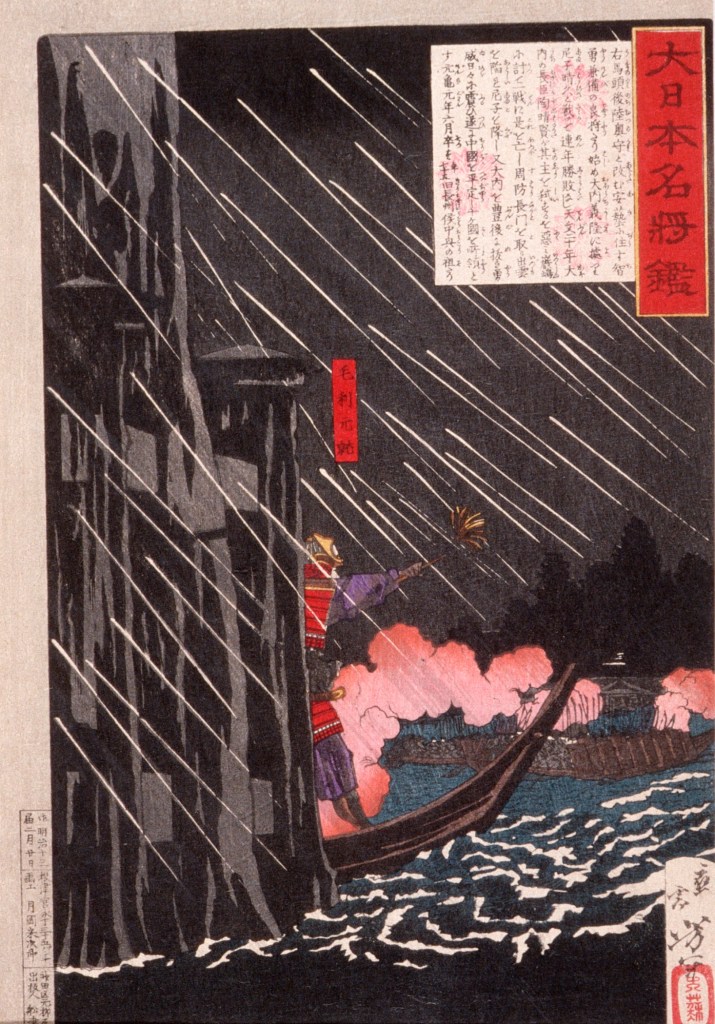

A year later, Harutaka himself led a large army to put down the Mori, laying siege to Miyao Castle on Itsukushima (site of the famous ‘floating’ Torii gate), with 20,000 men. Unbeknownst to Harutaka, however, was that this was exactly what Motonari had hoped he’d do. The Mori had one of the most powerful navies in Japan at the time, and what followed was a combined sea and land operation, in which the outnumbered Mori launched another surprise attack, trapping the Ouchi and effectively wiping them out, with Harutaka himself amongst the dead.

The Battle of Itsukushima was not the end of the Ouchi, but they were never again a serious force. Over the next two years, the Mori would expand into the former Ouchi heartlands of Suo and Nagato provinces, as well as advancing in Iwami Province, gaining control of the valuable silver mines there.

In a sign of how far things had changed, the Amago, who had previously been able to exert control over the Mori, now found that they had to deal with them on equal terms, with the conflict over the Iwami Silver Mines ending in the Mori’s favour.

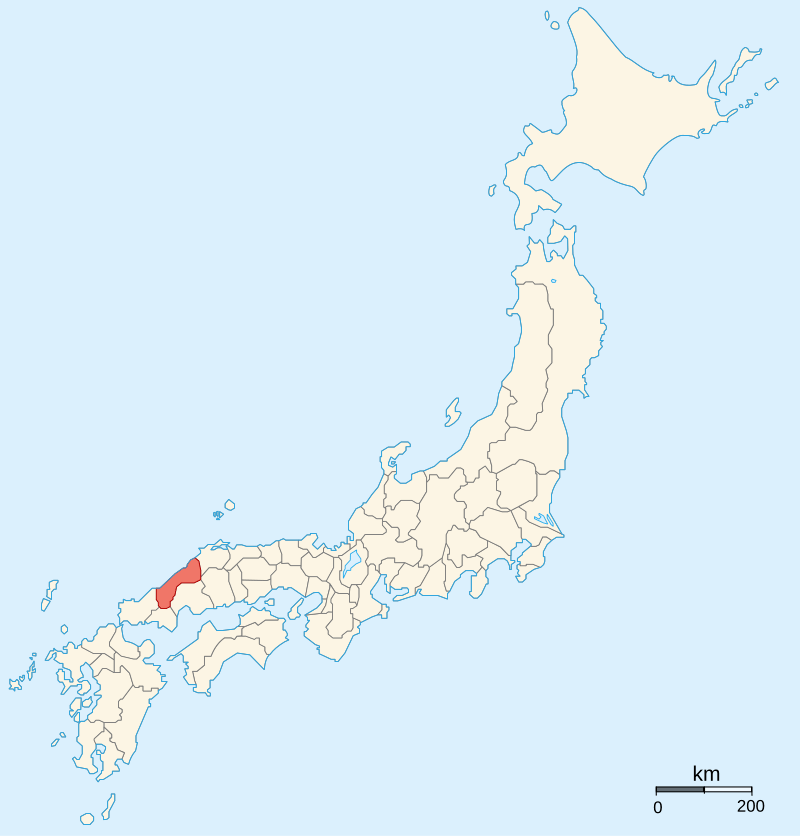

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1682513

In 1563, with Mori control reaching new heights, Takamoto, Motonari’s son and heir, died, leaving his son, Terumoto, as the new ‘leader’ of the Mori. The reality, of course, was that Motonari had retained control, and Terumoto was a child besides, leading to a kind of ‘dual leadership’, which was supposed to last until Terumoto came of age, but of course lasted much longer.

In 1566, Motonari, with Terumoto in tow, attacked the last Amago stronghold in Izumo province, forcing their surrender in November, and bringing a final end to the Amago, who had once been the region’s dominant power.

The next year, Terumoto was 15, and officially came of age, with Motonari announcing he would end the ‘dual leadership’. Apparently, Terumoto begged him to reconsider, and so Motonari would stay on as co-leader, though his health was already declining, and by the end of the 1560s, it was becoming clear that Motonari’s time was nearly up.

Mori Motonari would eventually pass away in June 1571, aged 75, possibly from cancer or old age. At his birth, the Mori had been a minor clan in a distant province, the proverbial leaf on the wind, buffeted to and fro depending on the whims of their powerful neighbours. As he lay dying 75 years later, Motonari ruled one of the largest territories of the era, and had established his clan as one of the truly great Sengoku Clans.

It would fall to his grandson, Terumoto, to continue this legacy, and though he would often prove equal to the task, fate was not yet done with the Mori Clan.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AF%9B%E5%88%A9%E5%85%83%E5%B0%B1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8E%B3%E5%B3%B6

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8E%B3%E5%B3%B6%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%98%B2%E9%95%B7%E7%B5%8C%E7%95%A5

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%8A%98%E6%95%B7%E7%95%91%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%90%89%E7%94%B0%E9%83%A1%E5%B1%B1%E5%9F%8E%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%90%89%E7%94%B0%E9%83%A1%E5%B1%B1%E5%9F%8E

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%AB%98%E6%A9%8B%E8%88%88%E5%85%89

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A6%99%E7%8E%96

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A3%AC%E7%94%9F%E7%94%BA_(%E5%BA%83%E5%B3%B6%E7%9C%8C)

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BA%95%E4%B8%8A%E5%85%83%E7%9B%9B

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aki_Province

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AF%9B%E5%88%A9%E8%88%88%E5%85%83