Oh yes, here we go, a good old-fashioned war post! All those posts about economic and social decline are finally paying off! Let’s get into it!

So, as we’ve discussed, by the mid-12th Century, the Imperial Court was in a bad way. Over the centuries, the throne had been dominated by one powerful clan after another, who would marry into the Imperial family again and again in order to maintain that domination, at the cost of turning their gene pool into more of a muddy puddle. Luckily, Heian Era Japan didn’t have a concept of genetics, so I’m sure it was fine.

The first of these families had been the Soga, who had been overthrown by the Fujiwara in the Isshi Incident in 645. The Fujiwara had had more or less complete control until the Emperors started abdicating to become insei, that is, cloistered Emperors, or an Emperor with all the power of the throne and none of the restraints that the Fujiwara had taken advantage of.

With the Fujiwara weakened, their enemies started circling. The Hogen Rebellion in 1156 marked the end of Fujiwara power, as the rival Taira and Minamoto families teamed up to take them down. In a betrayal that will surprise no one, the Taira then shafted the Minamoto in the post-rebellion settlement, taking most of the power and the influence over the Emperor for themselves.

The Minamoto were understandably a bit put out by that, so they launched a rebellion of their own in 1160. The so-called Heiji Rebellion failed, and the Minamoto were effectively wiped out, their leadership either killed or banished to the provinces.

For the next 20 years, the Taira ruled as the Fujiwara had, but the problem with a violent takeover is that once one group does it, everyone wants to have a go. The Taira, like the Fujiwara before them, became overly enamoured with court life and neglected the provinces.

This was unfortunate because, as I mentioned earlier, it was the provinces to which the Minamoto had been banished, and they weren’t in a forgiving mood when it came to the Taira.

The leader of the Taira at this point was Kiyomori. He had led the Taira forces that had overthrown the Fujiwara and then seen off the Minamoto, and he was probably feeling pretty pleased with himself. Using his influence (and presumably the implicit threat of force), he rose through the ranks at court, eventually becoming Daijo-Daijin, which was basically the head of the government and second only to the Emperor (in theory).

Now, there had obviously been Daijo-Daijin before Kiyomori, but he was significant because he was the first from the buke or warrior families to rise to that rank. Previously, the formal ranks of the Imperial Bureaucracy had been held by members or allies of the Fujiwara, and Kiyomori was an outsider who was seen as having used martial strength to gain his position, which was true, to be fair.

In 1171, Kiyomori cemented his power at court by having his daughter, Tokuko, marry Emperor Takakura. Now, none of this was particularly new; the Fujiwara had been doing it for centuries, after all, but Kiyomori was different; he was a thug.

The Fujiwara, for all their faults, had always played the game properly. They knew the rules, understood court etiquette, wrote beautiful poems, all that stuff. Kiyomori wasn’t like that. He’d taken power through military strength, and that was how he intended to keep hold of it. He wasn’t afraid to throw his weight around, and it was a risky business to oppose him.

In 1177, in response to an alleged coup (the Shishigatani incident), Kiyomori ordered the arrest of dozens of conspirators. That these conspirators were all people who had reason to be offended by Kiyomori was convenient, and some sources speculate that the plot never existed at all, as it appears to have relied entirely on the testimony of a single monk, who Kiyomori had tortured and then beheaded.

Regardless of whether it was real or not, Kiyomori had reinforced his power. Those who had ‘opposed’ him were dead or exiled, and he filled the vacant posts with family members and allies, further cementing his power and the fury of the opposition against him.

In 1178, Tokuko gave birth to a son, Antoku, and Kiyomori decided it’d be a good time to remind everyone at court who was really in charge. The so-called Political Crisis of the Third Year of the Jisho Era (which is a bit easier to say in Japanese, I assure you) was basically a military coup d’etat. Kiyomori brought thousands of his warriors from the provinces to the capital and took over.

There was no longer any pretence, Kiyomori was dictator in all but name, and shortly after the coup, he had Emperor Takakura abdicate in favour of the two-year-old Antoku, who obviously couldn’t rule himself, at which point Kiyomori kindly stepped in as regent.

You remember what I said about violent takeovers? Well, Kiyomori was about to learn that lesson. The Taira had driven out the Minamoto, but they hadn’t destroyed them, and for twenty years, Kiyomori had ruled in such a way that he alienated just about everyone.

In 1180, Prince Mochihito, who had been in line for the throne before Kiyomori raised the infant Antoku in his place, raised his banner in rebellion, calling for the opponents of the Taira to gather an army and march on the capital. Unfortunately, for Mochihito, his plan was discovered, and he was forced to flee, eventually arriving at the temple of Mii-Dera in Nara.

What follows is largely recorded in The Heike Monogatari, which is a pretty epic read, but is largely a fictionalised account of the war, presenting an idealised version of events, in which heroic warriors do heroic things against impossible (and often implausible) odds.

What we do know is that Mochihito, outnumbered and overwhelmed, was defeated at the Battle of Uji, just outside modern Kyoto, where he was either killed or executed shortly afterwards. Despite his unsuccessful attempts at raising an army, Mochihito’s call to arms did serve to galvanise the opposition to the Taira.

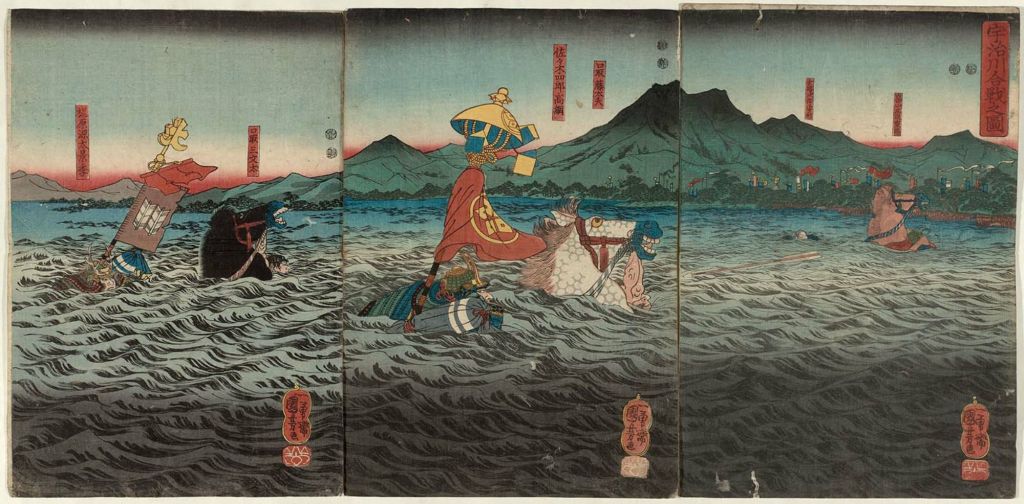

ColBase: 国立博物館所蔵品統合検索システム (Integrated Collections Database of the National Museums, Japan), CC 表示 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=92525963による

It is at this point that Minamoto no Yoritomo enters the stage, he definitely deserves a post of his own, but the short version is that he was 13 in 1160, and the Taira, perhaps feeling pity over his youth, hadn’t executed him, banishing him to the provinces instead.

Yoritomo, however, had a long memory, and he had spent the last twenty years gaining strength, first over his own clan, and then the surrounding area. His base was the city of Kamakura, in modern-day Kanagawa Prefecture, and it was a relatively long way from the capital.

When news of Uji reached him, Yoritomo set off looking for a fight. He called for help from the surrounding clans, and although there seems to have been some support, very few actually showed up to fight. In September 1180, Yoritomo had managed to gather just 300 men, and he was attacked by a force ten times that size at the Battle of Ishibashiyama.

Despite this defeat, Yoritomo was able to escape by sea to Awa Province (in modern Chiba Prefecture), from where he would continue the fight. Meanwhile, the Taira, under Kiyomori, sought to take revenge against the monks who had hidden Prince Mochihito, and attacked and burned the city of Nara.

Meanwhile, Yoritomo’s uncle was defeated at the Battle of Sunomatagawa in June 1181. The story goes that the Minamoto tried to sneak across a river at night in order to attack the Taira on the other bank. Apparently, their plan failed because Taira sentries were able to distinguish friend from foe by checking who was wet, or not. That seems like remarkable awareness for a battle in the dark, but regardless, the Minamoto failed to surprise the Taira and were defeated.

Later that year, Yoritomo’s cousin (and sometimes rival) Yoshinaka raised an army in the north and defeated the Taira army sent to stop him, after which, fighting died down for a while.

Taira no Kiyomori had died earlier in 1181 (the story goes that his fever was so hot anyone who tried to tend him would be burned), and not long after, a famine broke out that would spread across the nation. You can’t fight if you can’t eat, and so what followed was a two-year lull in the fighting, which I imagine wasn’t much comfort to the starving peasants.

The fighting would resume in 1183, and the Taira would have some initial success, but at the Battle of Kurikara Pass in June of that year, the Taira were decisively defeated, and the momentum shifted to the Minamoto. It was Yoshinaka (Yoritomo’s cousin) and Yukiie (Yoritomo’s Uncle, but not Yoshinaka’s father, I know, it’s confusing) who actually led the Minamoto to the capital.

As Kiyomori was dead, it fell to his son Munemori to lead the defence of the city. He did this by taking young Emperor Antoku and fleeing west, as you do. It was at this point that the cloistered Emperor, Go-Shirakawa (yeah, he’s still alive at this point!) threw in his lot with Yoshinaka and the Minamoto, calling on them to pursue and destroy the Taira.

Unfortunately, Yoshinaka had different plans. Fancying himself the rightful leader of the Minamoto, he engaged in a plot against his cousin, Yoritomo, who was by now marching from the East towards the capital. It seems he was initially joined by Yukiie, who then got cold feet and let details of the plot slip.

Yoshinaka himself became aware that the plot had been discovered and moved first, setting fire to several parts of the capital and taking Go-Shirakawa hostage. It was at this point that Yoritomo’s brothers, Yoshitsune and Noriyori, arrived with a considerable force. They drove Yoshinaka out of the capital, and then killed him at the Second Battle of Uji , bringing an end to the Minamoto Clan’s feuding (for now.)

After this, the momentum was decisively on the side of the Minamoto. They pursued the Taira, who had originally set up camp at Dazaifu, in Kyushu, and fortifying their positions around the Inland Sea, which were the lands the Taira had originally held.

The Minamoto went on the offensive and defeated the Taira at the Battle of Ichi-no-Tani, near modern-day Kobe, followed up by another victory at Kojima. These successes allowed the Minamoto to drive the Taira out of their strongholds along the coast of the Inland Sea.

The Taira, in possession of what was apparently the only navy in Japan at the time, and certainly the strongest, retreated to Shikoku, knowing that the Minamoto couldn’t follow. The Minamoto weren’t going to just let the Taira get away, however, and although it took time, they built up their naval strength before launching an attack at Yashima, in modern-day Takamatsu, that took the Taira fortress there, which had also been used as a makeshift palace for Emperor Antoku.

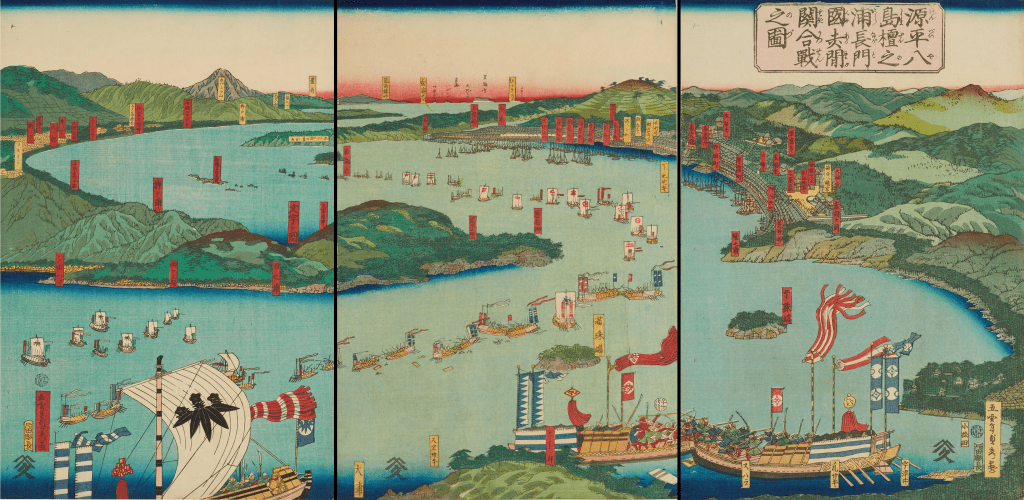

Driven out of yet another stronghold, the Taira took to their ships and fled. The Minamoto would catch up to them at Dan-no-Ura, in the Straits of Shimonoseki. If you believe the Heike Monogatari (which you shouldn’t), then the Minamoto had 3000 ships to the Taira’s 1000. According to the Azuma Kagami, which is a biased by slightly more believable source, the forces were actually around 800 to 500, which are still considerable forces, but a bit more plausible.

Despite being outnumbered, the Taira had home advantage and knew the tides and currents better than their foes. They also had the Emperor with them, which they assumed would give their side more legitimacy and encourage their men to fight harder.

It was a good idea in theory, but it didn’t work. Though the tides were initially in the Taira’s favour, they turned, as tides do, and one of the Taira’s commanders turned as well, as men often do. Surrounded and attacked from all sides, the Taira began committing suicide en masse. One of those who died was six-year-old Antoku. The story goes that his grandmother, Taira no Kiyomori’s widow, took the boy in her arms and jumped with him into the sea. Neither was seen again.

The Taira also tried to get rid of the Imperial Regalia, tossing them overboard. However, they apparently only managed to dump the mythical Kusanagi Sword and the Yasakani Jewel. The Yata no Kagami, a sacred bronze mirror, was apparently saved when the woman who tried to throw it overboard was killed when she accidentally looked at it.

All three items were apparently recovered, either on the day of the battle or later, by divers. They are supposedly housed at the Ise Shrine in Mie Prefecture. The fact that no one has been allowed to see the artefacts since Dan-no-Ura is apparently just a coincidence.

The result of Dan-no-Ura was the end of the Taira as a serious political force. Later that year, the Emperor Go-Shirakawa gave Minamoto no Yoritomo the right to collect taxes and appoint officials, effectively handing control of the state over to him.

Though it would be some years before Yoritomo would take the formal title, the Genpei War marks the time at which control of Japan shifted from courtiers and Emperors to warriors under a supreme military commander who took a title that had first been used in the earliest days of Imperial rule in Japan, Sei-i Tai Shōgun.

Cue dramatic music

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Dan-no-ura

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Uji_(1184)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Azuma_Kagami

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B1%8B%E5%B3%B6%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Yashima

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%80%E3%83%8E%E8%B0%B7%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%97%A4%E6%88%B8%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%BA%90%E8%A1%8C%E5%AE%B6

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%80%B6%E5%88%A9%E4%BC%BD%E7%BE%85%E5%B3%A0%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Kurikara_Pass

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minamoto_no_Yukiie

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minamoto_no_Yoshinaka

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Sunomata-gawa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Ishibashiyama

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BB%A5%E4%BB%81%E7%8E%8B

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_Mochihito

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emperor_Takakura

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emperor_Antoku

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taira_no_Kiyomori

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Tale_of_the_Heike

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Uji_(1180)

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%B2%BB%E6%89%BF%E3%83%BB%E5%AF%BF%E6%B0%B8%E3%81%AE%E4%B9%B1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%B2%BB%E6%89%BF%E4%B8%89%E5%B9%B4%E3%81%AE%E6%94%BF%E5%A4%89

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shishigatani_incident

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%B9%BF%E3%82%B1%E8%B0%B7%E3%81%AE%E9%99%B0%E8%AC%80

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genpei_War

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minamoto_no_Yoritomo