Last time, we talked about the Jomon People, Japan’s first inhabitants. Those folk existed primarily as Hunter-Gatherers, but around the year 900 BC, a new wave of culture crossed the Tsushima Strait from Korea. No, it’s not some prehistoric version of BTS (can you even imagine?), but settled villages, metalwork, and, most significantly, rice.

Nowadays, we arguably take agriculture for granted; unless you live and work in the countryside, you may never think about it at all, but the ability to cultivate land and produce crops on it changed humanity. For the first time, our ancestors could produce more food than they needed, and if one man could produce enough food for himself and four or five others (mileage may vary), then those four or five others are no longer needed in the fields, which means they can spend their time doing other things, like art, music, war, and ruling over the farmers. (Ok, so it’s not all good.)

Agricultural revolutions occurred pretty much everywhere at different times, but the Yayoi period is generally thought to have begun around 300 BC. Now, I have to point out that that is not an exact chronology, firstly, because these things never are, and secondly, because the exact transition between the Jomon and Yayoi periods is pretty murky in some places.

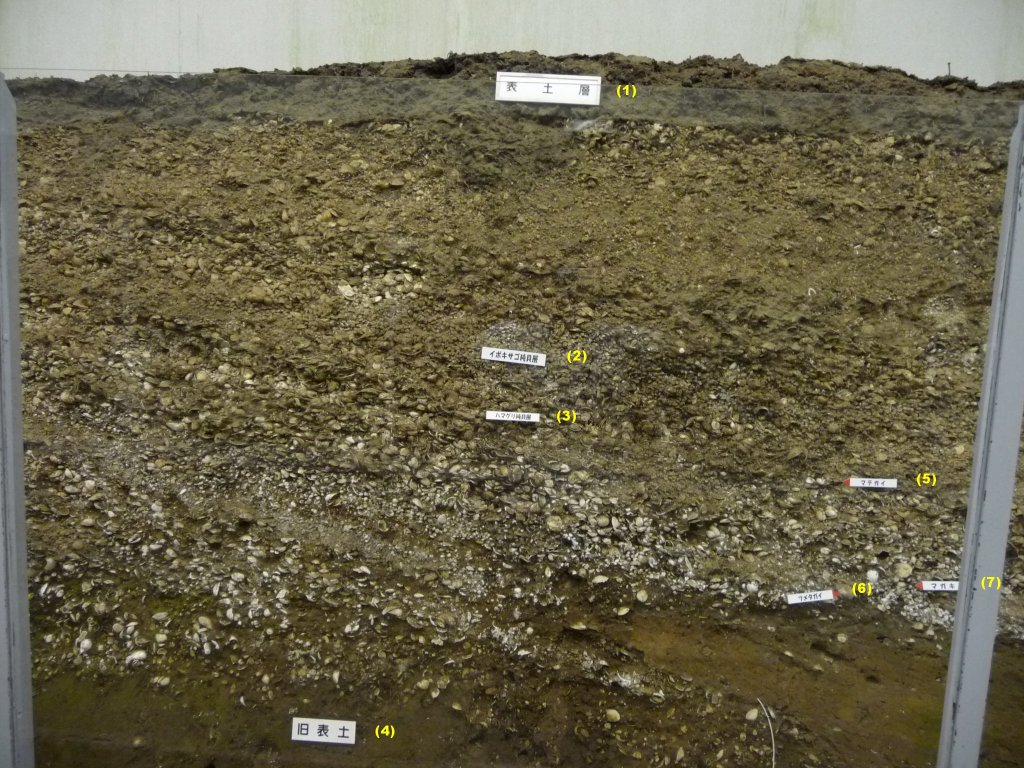

For example, at the Itazuke Site in Fukuoka Prefecture, the earliest remains of rice paddies have been found in contexts that put them more in the Jomon period than the Yayoi, leading some scholars to suggest that the Yayoi period should actually be dated as starting as early as 800 BC, or perhaps even earlier. However, this remains controversial, and there’s never likely to be an exact timeline.

By Muyo – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15136810

While Itazuke probably represents a transitional site, it does raise some interesting questions. For example, was the appearance of irrigated rice paddies a case of technological spread, or was it brought over by waves of immigration? The answer, broadly, is a bit of both.

The thing with ancient, pre-literate societies is that they weren’t generally big on keeping written records, and something as formal as a census was right out. Consequently, it’s pretty difficult to guess exactly how many people were living in Yayoi Japan; it’s also tricky to figure out where they came from.

The first suggestion is that the Yayoi peoples represented a series of massive waves of migration over a 500 to 600-year period. Some estimates put the population of Japan at somewhere around 6 million by the end of the Yayoi Period in 300 AD. This represents a population increase of more than 4 million over that period, which some scholars suggest is impossible to explain as being a result of immigration alone.

Now, this isn’t the sort of blog that’s going to go into where babies come from (there’s plenty enough of that sort of thing on the internet already), but a basic rule of thumb for any society is that food surplus = people surplus. If you have a reliable food source and aren’t running for your life from sabertooth tigers and the like, you’re more likely to have a baby, and what’s more, that baby is more likely to survive to adulthood.

For archaeologists, the next step is trying to figure out who is having the babies. It’s the women, obviously, but the Yayoi people represent an interesting example of how populations change over time.

Genetically speaking, you can divide the Yayoi into three broad groups: Early, Middle, and Late. So named because they came to Japan at different times (guess which is which!)

All three groups share similar genetic traits, suggesting shared ancestry, but while human remains of early Yayoi people show a larger percentage of Jomon DNA, suggesting that immigrants and locals were pretty friendly, the later generation shows much less Jomon DNA, and much more from groups that inhabited Korea at the same time.

Now, does that mean that the later waves of immigrants were pickier in their partners, or, does it mean that by the later Yayoi Period, anyone with large amounts of Jomon DNA had already moved away, or, to put it bluntly, been bred out of existence?

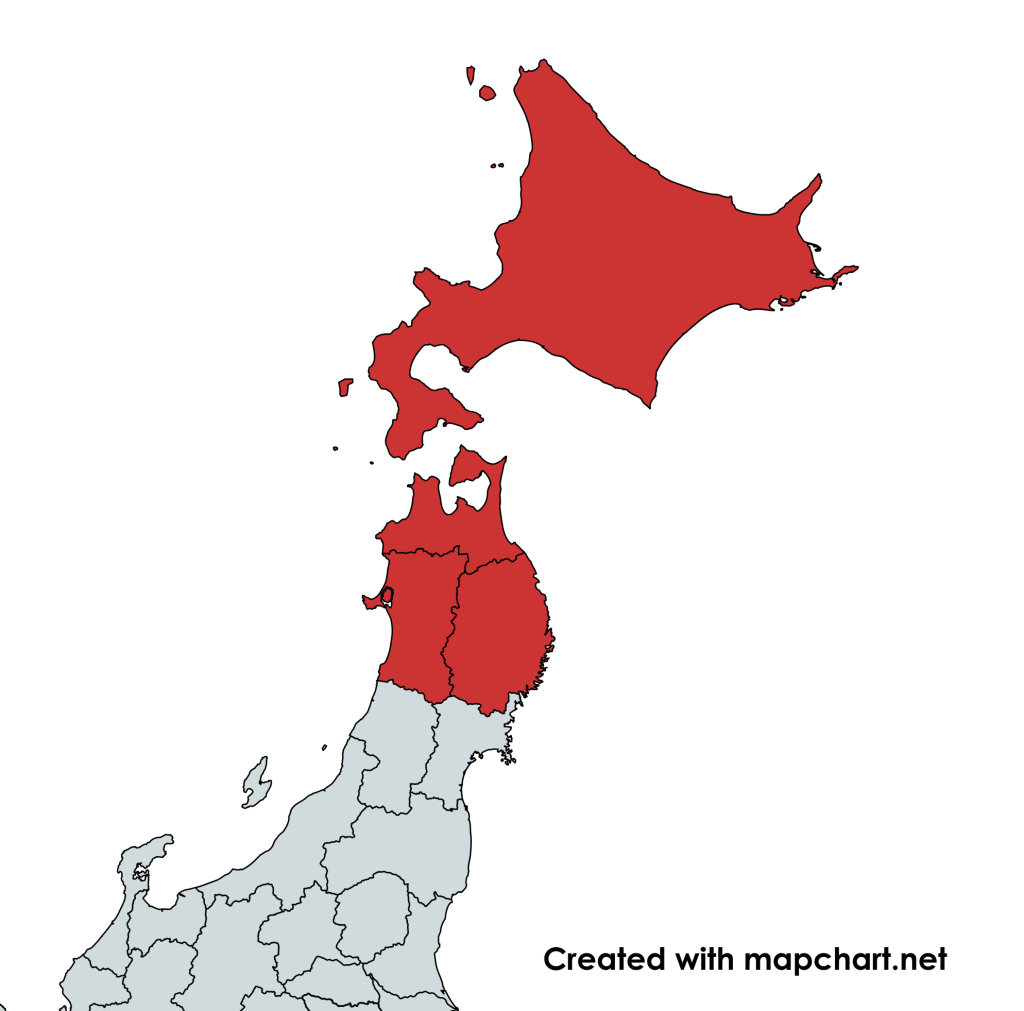

The answer is unclear, but probably. We know that the Yayoi and Jomon populations were genetically distinct. We can also estimate that the population during the Jomon Period was around 75,000, whereas by the end of the Yayoi Period, it was 6 million. Outside of Hokkaido, then, it seems reasonable to state that Jomon people were simply swamped.

Yayoi Culture

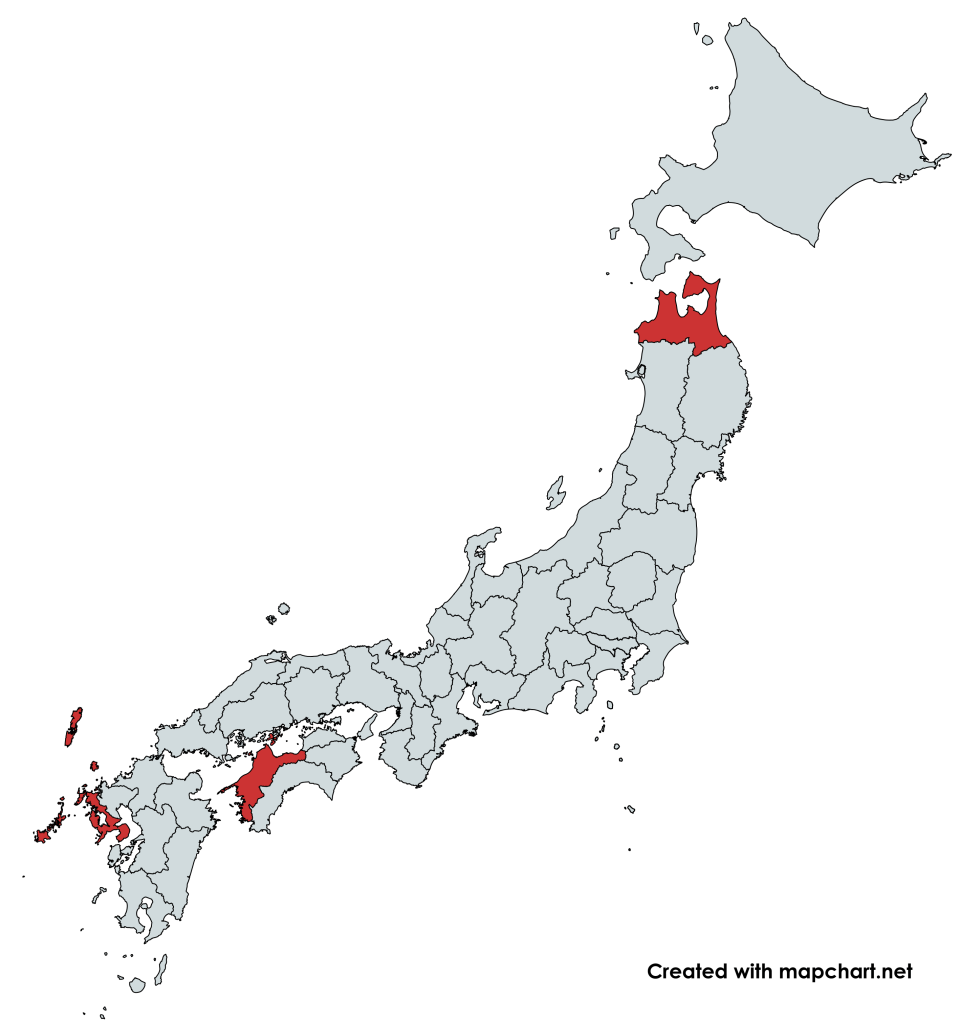

Whilst the Jomon and Yayoi peoples were playing a long-term game of “Kiss, Marry, Avoid” (I know that’s not what it’s really called, but I’m trying to keep things PG), Yayoi culture and language were beginning to spread across the land. It should be pointed out, however, that the spread was not even, nor was it universal. Whilst Yayoi culture came to dominate in Kyushu, in Honshu, the adoption of rice farming and other Yayoi hallmarks was pretty inconsistent.

For example, evidence of agriculture has been found in the Hokuriku region dating back to 380 to 300 BC. However, in the Tokai region, which is practically next door, the first evidence doesn’t appear until 220 BC in some areas, and as late as 50 BC in others.

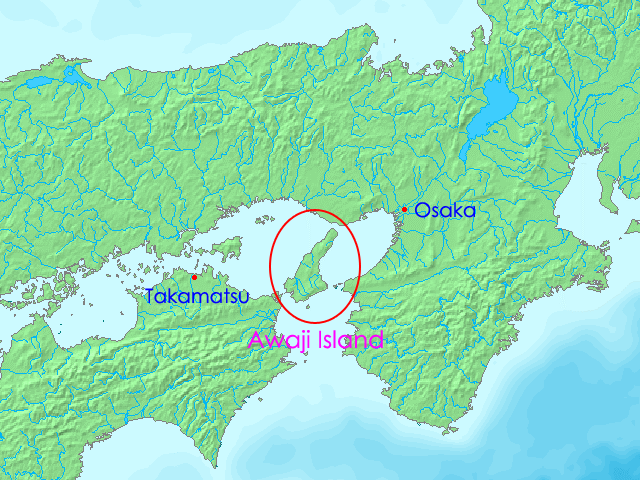

This inconsistent development isn’t as random as it may first appear. It is generally believed that the Yayoi peoples were a so-called “sea” people, meaning that they came across from Korea and Eastern China by boat (because how else are you going to do it?). It is then reasonable to assume that the transmission of Yayoi culture would follow coastal routes first, before spreading inland over the following decades.

Rise of Yamatai

One of the major problems we have with ancient civilisations (some of them, anyway) is that they didn’t write things down. Now, this is likely because they didn’t have a written language, but it’s still a pain. The Yayoi are one such example. What we know about them comes from the archaeological record, and although archaeologists are (usually) pretty good at what they do, without a clear written record, it can be challenging to figure out exactly how the Yayoi people saw themselves.

Luckily for us, other people nearby did have writing, and they were kind enough to leave some records. The Chinese Han Dynasty kept copious amounts of records about their neighbours, and it is in these sources that we see the first mention of the Japanese islands.

In the Book of Later Han, in 57 AD, the Chinese Emperor Guangwu gave the Kingdom of Na a gold seal and some other fancy gifts in exchange for the King of Na recognising the Chinese as their overlords. For centuries, the seal, and indeed the Kingdom of Na, were considered to be semi-legendary, but then the seal itself was discovered by accident (by a farmer, apparently), confirming that the Chinese records were accurate and Na (Nakoku in Japanese) really existed.

By Original uploader: User:金翅大鹏鸟 at zh.wikipedia – Transferred from zh.wikipedia to Commons by Shizhao using CommonsHelper., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15840653

There are sporadic records of other Kingdoms and Tribes existing around Japan (called ‘Wa’ by the Chinese), but their exact nature and even their locations are often a mystery. One state from that era that has had an enduring legacy is Yamatai (Yamataikoku in Japanese.)

This state features prominently in contemporary Chinese records and was apparently ruled by Queen Himiko, or, in some cases, the “King of Wa,” suggesting that the Chinese believed Yamatai to be the rulers of the whole of Japan (as they understood it) or at least a Kingdom of preeminent power.

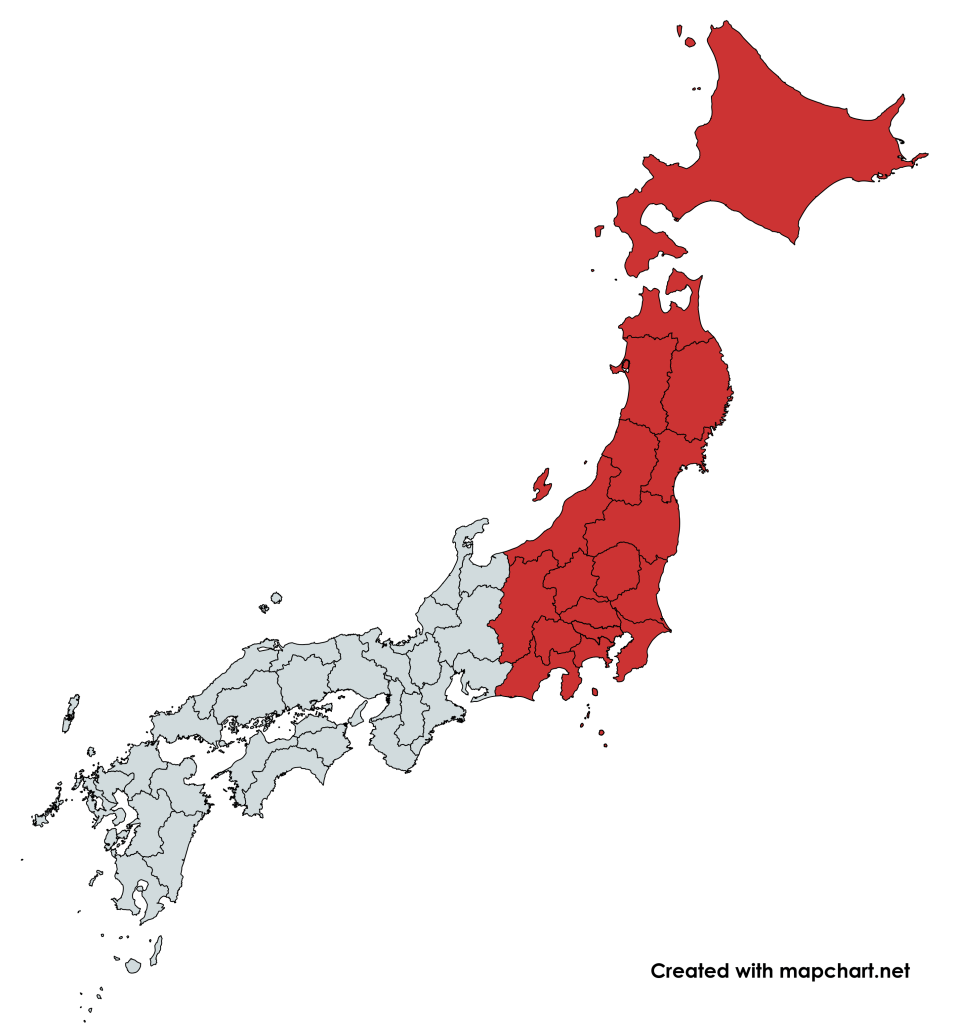

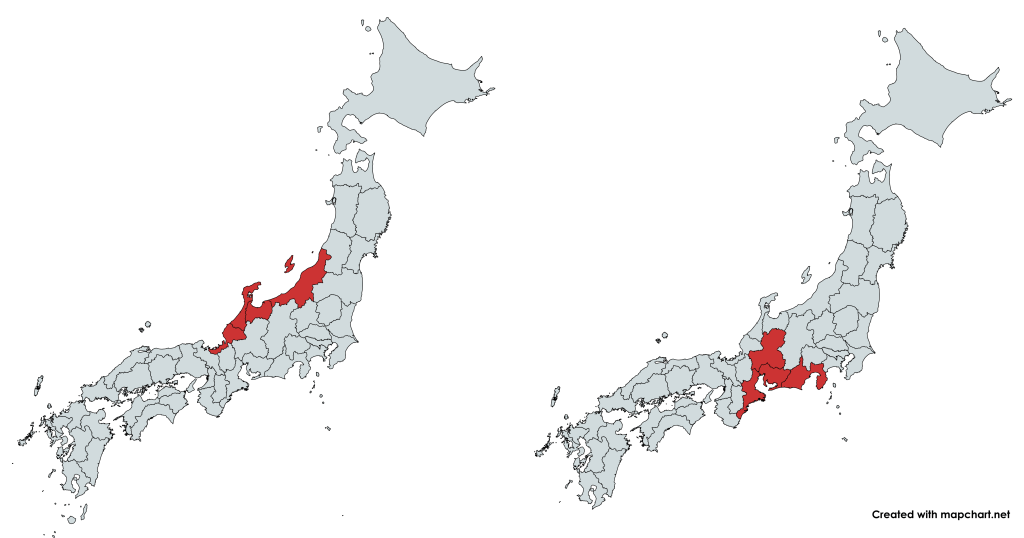

We know very little about Yamatai itself, as the only documentary sources are Chinese records, and the archaeological record is unclear. We’re not even sure where Yamatai was located within Japan, with Northern Kyushu or the Kinai Region (near modern Kyoto, Osaka, and Nara) being proposed.

By Flora fon Esth – Own work based on the image Provinces of Japan.svg (GFDL et CC-by-3.0), CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=160605946

The discovery of the Yoshinogari site in 1986 ignited the popular imagination, and Yamatai and Queen Himiko have been figures in popular culture ever since. Some have suggested that Yoshinogari is a good candidate for the supposed capital of Yamatai. However, this remains highly controversial, and most experts state that Yoshinogari is an important site, but there’s no evidence to support the assertion that it is the capital.

By ja:User:Sanjo – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4954364

Queen Himiko is said to have died around 248 AD, after she was replaced, first by a King whose name is not recorded, and then by Toyo (Iyo in some records), about whom very little is known.

When Himiko passed away, a great mound was raised, more than a hundred paces in diameter. Over a hundred male and female attendants followed her to the grave. Then a king was placed on the throne, but the people would not obey him. Assassination and murder followed; more than one thousand were thus slain. A relative of Himiko named Iyo [壹與], a girl of thirteen, was [then] made queen and order was restored. (Zhang) Zheng (張政) (an ambassador from Wei), issued a proclamation to the effect that Iyo was the ruler.

Tsunoda, Ryusaku, tr (1951), Goodrich, Carrington C (ed.), Japan in the Chinese Dynastic Histories: Later Han Through Ming Dynasties, South Pasadena: PD and Ione Perkins, taken from Wikipedia.

Ultimately, Yamatai would disappear from the records shortly after Iyo came to the throne, and, as with any records over such long periods of time, we should take the details with a grain of salt.

That being said, thanks to Chinese records and the hard work of local archaeologists, we know that by the end of the Yayoi Period, kingdoms had begun to emerge across Japan. Like the preceding Jomon Period, the Yayoi Period can’t really be said to have ended, so much as it transitioned into something else.

Some scholars suggest that Yamatai lent its name to the following Yamato Period, although the exact etymology isn’t clear (nothing ever is with this stuff.)

Next time, we’ll take a look at the Yamato Period, Japan’s first Imperial State.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yamatai https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yoshinogari_site https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nakoku https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yayoi_period https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yayoi_people https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/regional-variations-in-the-demographic-response-to-the-arrival-of-rice-farming-in-prehistoric-japan/7E6D28520A04B2F07DDD36908F291808 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/evolutionary-human-sciences/article/japan-considered-from-the-hypothesis-of-farmerlanguage-spread/BD91E69AEA3CCAEDC567519EF7F5AA97