Late 15th-century Japan was a chaotic place, but as we all know by now, chaos also presents opportunity. As central authority declined, local clans would move to fill the void. Some of these clans would fall almost as quickly as they had risen, others would continue to survive in one form or another throughout the Sengoku Period, and a select few would go on to be truly great.

The focus of this post is one of them, the Hojo (hence the title). Right away, I want to be clear that this Hojo and the Hojo we looked at previously (the ones who were regents during the Mongol Invasions) were not related, despite the same name and mon. Sometimes, this second Hojo Clan is called the “Later” Hojo (Go-Hojo) in Japanese, but for our purposes, we’ll just call them the Hojo and hope you remember the distinction.

Adding to our confusion, the founder of the clan, Hojo Soun, wasn’t actually called that. He was a member of the Ise Clan, and it was his son, the second “Lord” Hojo, who adopted the name and mon. Again, while it is technically more accurate to refer to this founder as Ise Souzui, we’ll call him Hojo Soun, because a) that’s the name he’s best remembered by, and b) it’ll get confusing if we keep changing his name.

Side Note: Name changes were common in Japanese culture, with someone’s birth name rarely being the name they are recorded by historically. When you factor in nicknames, titles, honorifics, etc, you have individuals who may have gone by any number of names. Up until now (and continuing after this), I have always called historical characters by their most commonly used name, just in case you were wondering.

The man who would become Hojo Soun is the subject of considerable mythologising. In the pre-modern period, it was widely assumed that he had been a poor samurai who had risen to a position of power by sheer force of will, pulling himself up by the proverbial bootstraps.

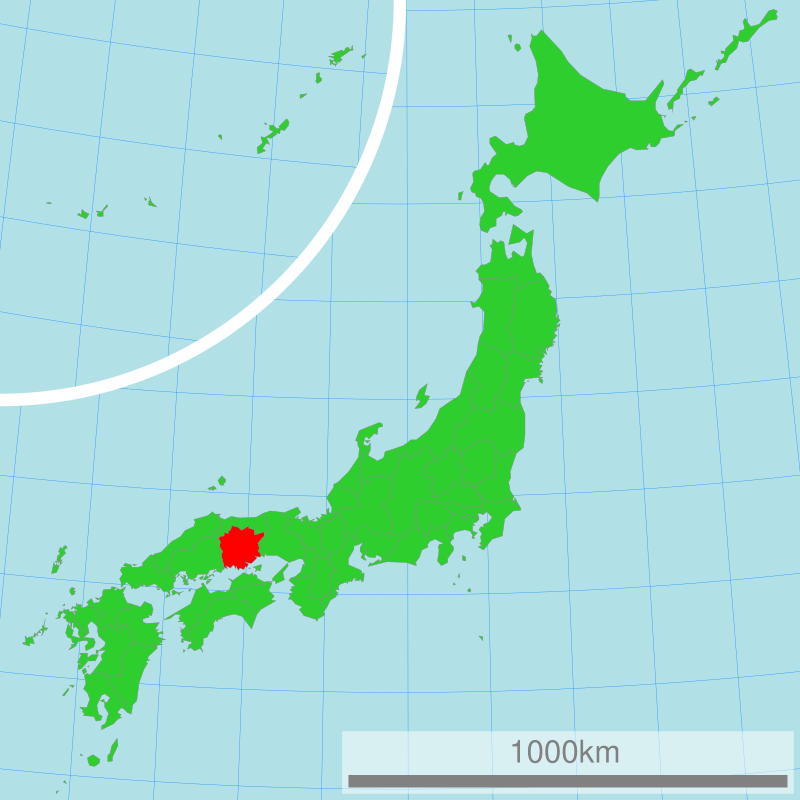

20th-century scholarship has shed more light on his origins, however. He was a member of the Ise Clan, as we mentioned previously, and was born either in Kyoto or Ibara, in modern Okayama Prefecture. His family were not at the highest ranks, but they were administrators for the Shogun, meaning that they were often close to the centre of power and were certainly not the impoverished provincial family of later myth and legend.

By Lincun – 国土交通省 国土数値情報(行政区域), CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3916728

Soun’s exact origins are still a little unclear (we’re not even 100% sure what year he was born, though 1456 is considered most likely), but his rise to power came during the chaotic violence of the Onin War. As we looked at previously, one of the ancillary conflicts was in the Kanto, where Ashikaga Shigeuji and the Uesugi Clan clashed violently. Officially, Shigeuji was a rebel against the Shogunate, and the Uesugi were loyal servants, although in reality, neither side paid much attention to the capital.

One of the other clans in the Kanto at this time was the Imagawa, who remained loyal to the interests of the Shogun. In 1476, the head of the Imagawa was killed in battle, and his heir was just a boy (Ujichika). Factions quickly formed within the clan seeking to assert rival claims to leadership.

With the clan fracturing and external rivals seeking to take advantage, Soun, who was the brother of Lady Kitagawa, Ujichika’s mother, is said to have arrived at the Imagawa home in Suruga Province (in modern Shizuoka) to negotiate a peaceful settlement at the request of his sister. An agreement was reached in which the cousin of the previous leader (Norimitsu) would stand in as acting leader until the young boy came of age, whilst the rival factions were convinced (or compelled) to withdraw.

It is debated exactly what role Soun played in this negotiation. It is noted that he was very young (perhaps 20 or 21) to be a negotiator, and his name doesn’t appear in any official government records. The withdrawal of rival forces is also suggested to have been a reaction to problems elsewhere (the Uesugi faced rebellion at home, for example) and not a result of Soun’s negotiating prowess. While peace was certainly achieved within the Imagawa Clan, it is entirely possible that Soun’s role in achieving it was minimal, or perhaps even a later fabrication.

The first ‘official’ records of Soun come from the period of 1481-87, when he is recorded as a subordinate to the Shogun, presumably taking some role in the administrative affairs of the government. It is also speculated that Soun’s later departure for Suruga Province was motivated by legal troubles surrounding unpaid debts. Again, the exact nature of this problem isn’t clear, but there was certainly a legal case involving Soun and one of his creditors dated to this period, although the outcome is apparently lost.

In 1487, the previous agreement that had led to peace within the Imagawa Clan broke down. Norimitsu, who had been chosen to stand as ‘regent’ during the minority of Imagawa Ujichika, refused to step down. Although Soun’s role in the initial negotiation is debated, he certainly returned to Suruga Province around this time to force a settlement, apparently with the approval (or possibly at the direct order) of the Shogun and at the request, once again, of his sister, Lady Kitagawa.

Norimitsu had once been able to call on the support of external clans, but the political situation in the Kanto had changed in the decade since the original settlement, and that support no longer existed. Soun based himself at Ishiwaki Castle (in modern Yaizu, Shizuoka) and gathered supporters of Ujichika to his banner.

alonfloc, CC 表示 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=52973978による

In late 1487, Soun led an attack on Norimitsu and his supporters, defeating them in a short, sharp campaign that ended with Norimitsu’s suicide and Ujichika’s confirmation as leader of the Imagawa Clan. Soun was rewarded for his actions, but the exact location of his new lands is disputed, with several possible locations including the aforementioned Ishiwaki Castle.

Though the exact location of his base isn’t known for sure, Soun certainly remained in Suruga Province in the immediate aftermath of his success, acting as a protector for the young Ujichika. It is also suggested that during this period he acquired or was rewarded with estates in Izu Province, though again, that isn’t recorded with certainty.

Soun’s actions following this are murky; he appears to have returned to the direct service of the Shogun in around 1491, though he seems to have remained physically in Suruga Province. In 1493, the Meio Coup changed Soun’s situation considerably, although again the exact circumstances are open to speculation.

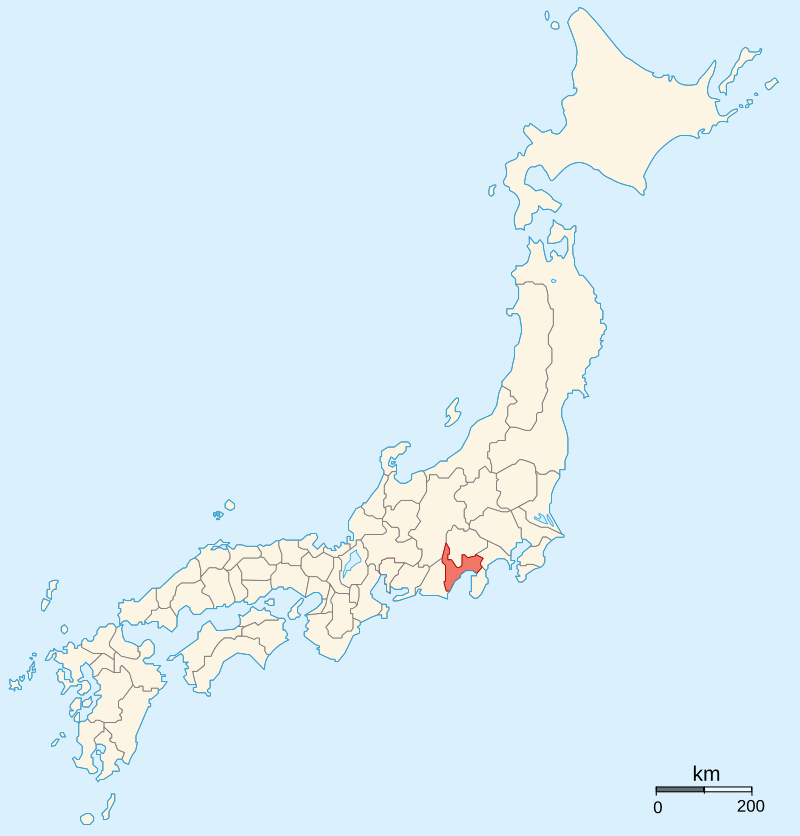

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1691794

What is certain is that Soun would lead an attack into neighbouring Izu Province that would eventually see him take control of the entire province. Some sources suggest that Soun was acting on the orders of Hosokawa Masatomo, the instigator of the Meio Coup; others indicate that Soun was acting on his own initiative. The situation in the Kanto was already volatile, and the coup in Kyoto had only made things worse, giving Soun a chance to improve his fortunes.

Soun’s actual conquest of Izu is subject to considerable mythologising, with some stories telling us that he spied on the province in person, posing as a pilgrim to the area’s many hot springs, whilst others say that he was welcomed as a liberator and kept his army under tight control, preventing any pillaging. Soun is also supposed to have secured the province in under 30 days, launching a surprise attack on the residence of the previous lord of Izu, and either killing him or forcing him to commit suicide.

The reality seems to have been a protracted campaign, with Soun trying to capture the leader of the province in a rapid advance, but failing to do so, leading to a drawn-out war that would not be finally resolved until 1498, though the historical record does seem to suggest that Soun’s victory was more or less guaranteed after around 1495.

Despite his conquest of Izu, Soun remained a nominal vassal of the Imagawa Clan and took an active part in their campaigns in the Kanto. He would campaign on their behalf in Kai Province, and in Sagami (modern-day Yamanashi and Kanagawa Prefectures), famously capturing Odawara Castle in late 1495. The legends tell us that Soun captured the mighty fortress through trickery, convincing the lord to go hunting and then taking the castle while he was away. Modern scholars suggest that a large earthquake that year undermined the fortifications of Odawara and made holding it untenable.

By 柴錬アワー – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=81578474

In the short term, Soun would continue to support the Imagawa Clan, but as time went on, he began to take on an increasingly independent appearance, as his power grew, and the Imagawa found themselves distracted by events elsewhere. In 1507, the Eisho Disturbance (which led to the Hosokawa Rebellion we talked about previously) ended what little remained of Shogunate influence in the Kanto, and with the Imagawa distracted (or by some accounts, overstretched), Soun was able to extend his direct control of Sagami and Izu Provinces.

Soun would clash with the Miura Clan of Sagami, who were in turn supported by the Ogigayatsu branch of the Uesugi Clan. Soun would advance on Edo Castle (on the site of the modern Imperial Palace in Tokyo) in early 1510, but a counterattack by the Miura and Ogigayatsu would drive him back as far as his base at Odawara.

Soun would survive this crisis, and the destruction of the Miura Clan is said to have become the singular focus of his later life. Starting in the summer of 1512, Soun would make steady advances against the Miura, driving them out of Sagami Province, and defeating supporting attacks from the Ogigayatsu, until, by July 1516, the Miura had been bottled up in the eponymous Miura Peninsula (in modern Kanagawa Prefecture) before being destroyed with the capture of their final fortress at Misaki Castle.

Soun would engage in several further campaigns, even crossing into modern Chiba, but in 1518, he handed control of the clan over to his son, Ujitsuna, before passing away in August the following year.

Though Soun himself would never take the name Hojo, his actions secured the dominance of his clan in the Kanto region for most of the 16th Century. Though they would never be completely unchallenged, the clan would eventually rise to become masters of the area around modern Tokyo, until they eventually fell foul of Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s campaigns to unite the realm, with their mighty fortress at Odawara being taken, and the clan destroyed in 1590.

In many ways, Soun is the archetype of what would become known as a “Sengoku Daimyo”, a kind of warlord who was not content with simply fighting with his neighbours, but worked to improve the lands he ruled. In 1506, Soun ordered a land survey in Sagami Province, the first of its kind in this new era, and he would introduce sweeping reforms to law and justice in his territories that would serve as inspiration for generations of Samurai that followed him, and in some cases, formed the basis for the legal system in place during the Edo Period, and even into more modern times.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8C%97%E6%9D%A1%E6%97%A9%E9%9B%B2

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%BE%8C%E5%8C%97%E6%9D%A1%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%89%E6%B5%A6%E5%8D%8A%E5%B3%B6

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%AB%8B%E6%B2%B3%E5%8E%9F%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84