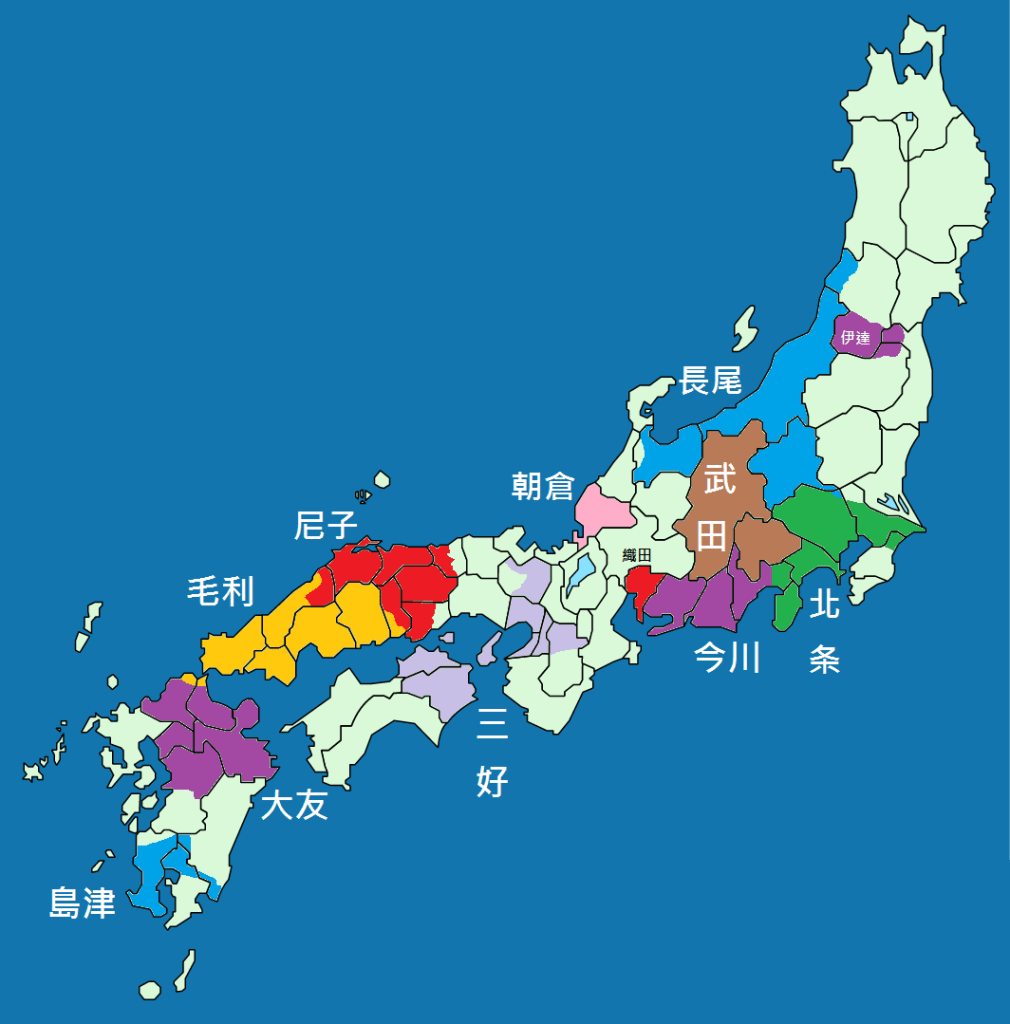

Hojo Ujiyasu died in 1571, having lived a life in which he had seen the fortunes of his clan rise, fall, and then rise again. His son, Ujimasa, inherited a strong but still dangerous position. Almost as soon as his father had passed, Ujimasa sought to end the war with Takeda Shingen and reestablish an alliance against their mutual enemy, Uesugi Kenshin.

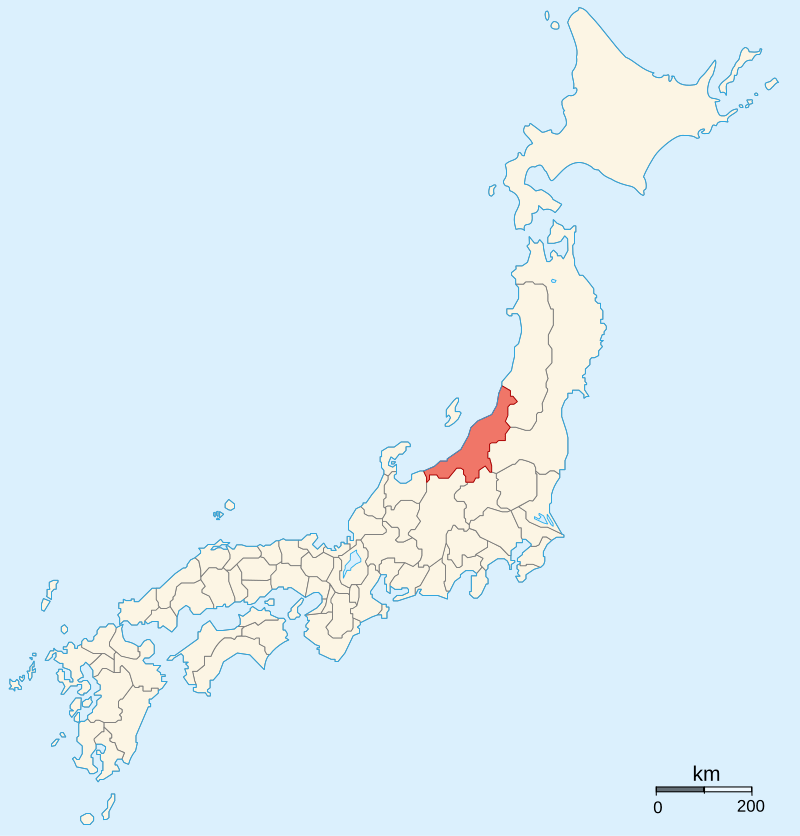

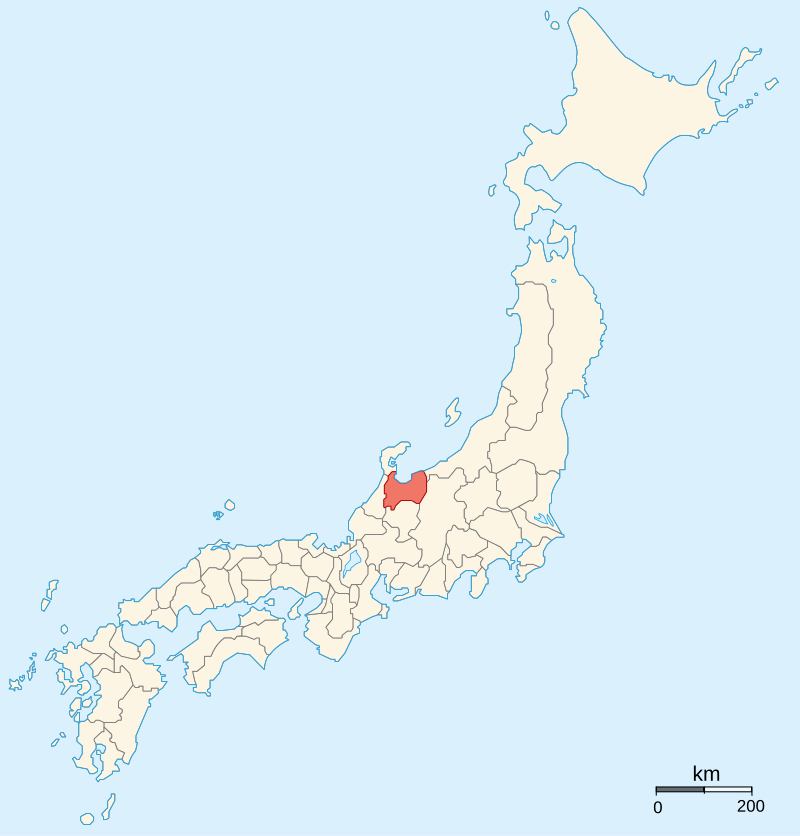

Shingen, by now in control of Suruga and stronger than ever, agreed, and it didn’t take long for the Hojo and Uesugi to be at each other’s throats again. In 1574, Kenshin invaded the Kanto, but his attention was focused mostly on his conflict with the Takeda, closer to home, and this round of Uesugi-Hojo fighting ended after an indecisive battle at the Tone River.

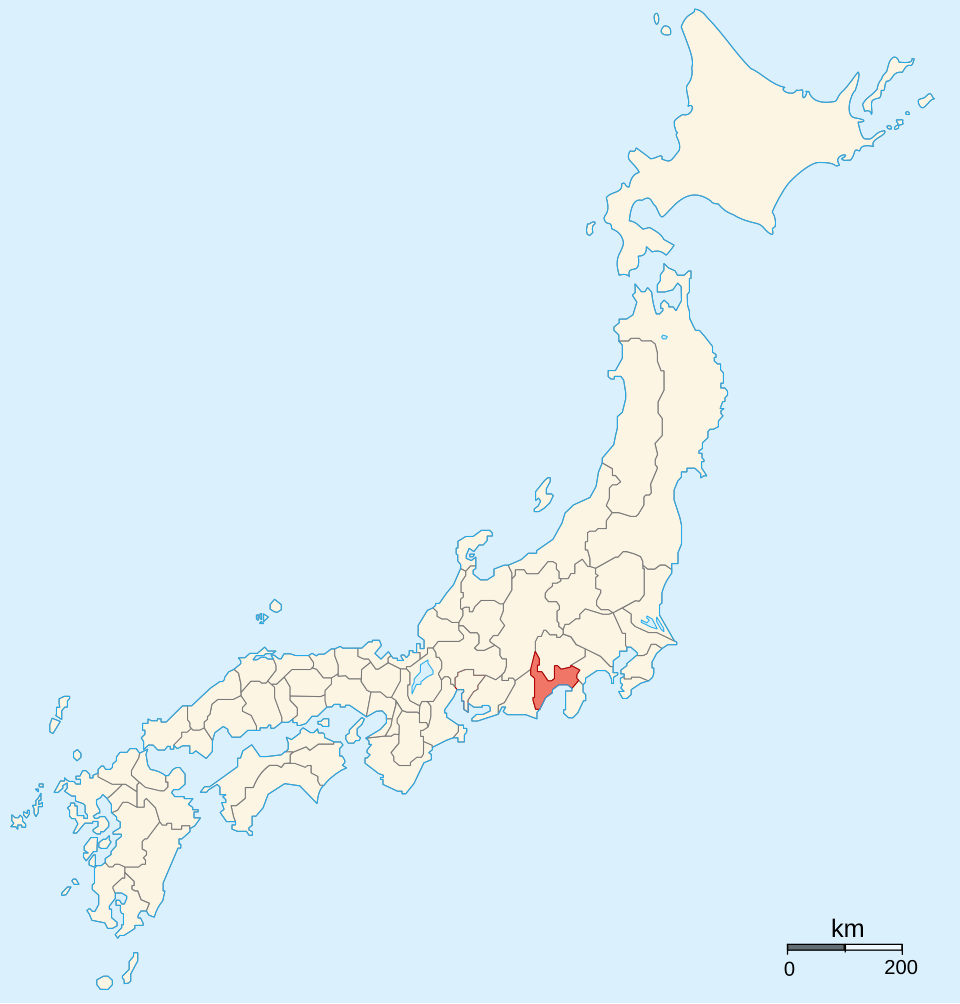

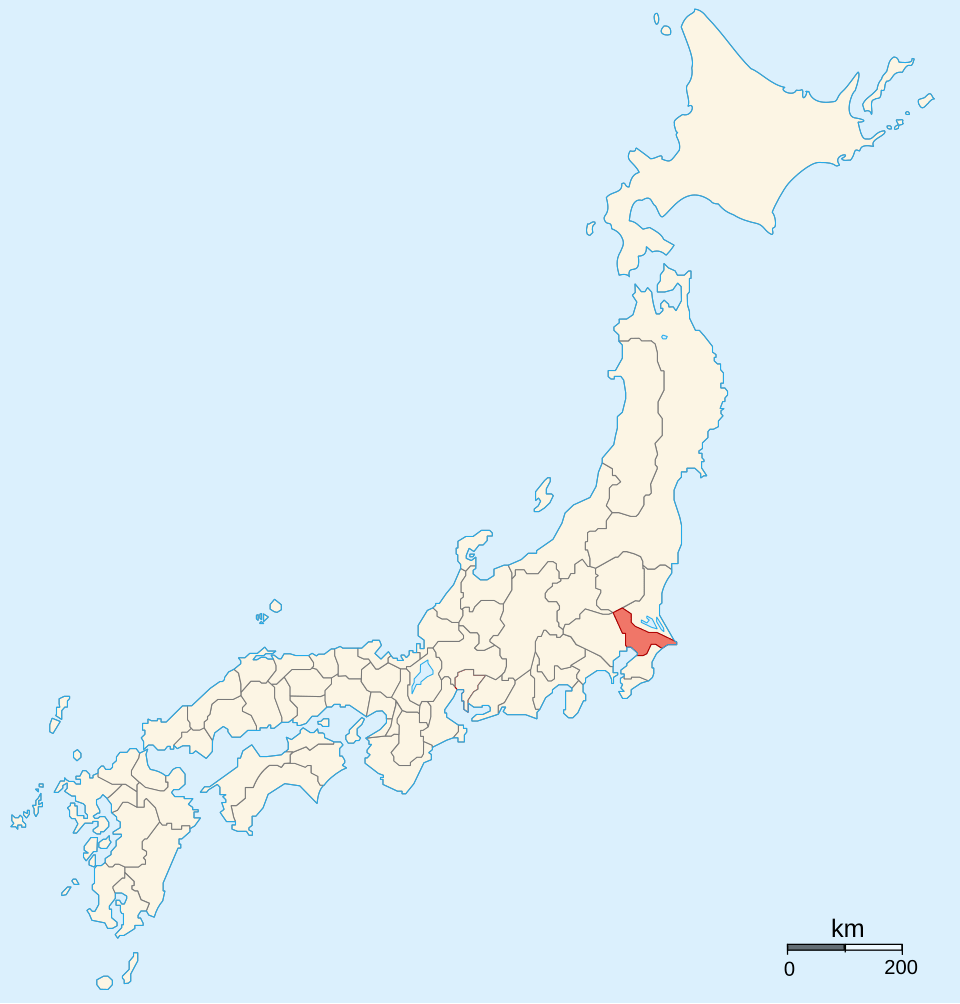

With Kenshin busy elsewhere, Ujimasa turned his attention back to the Hojo’s old enemy, the Satomi, invading Shimotsuke in 1576, and advancing deep into Kazusa the next year. The Hojo clearly had the military advantage, with a vastly superior army and much larger territory. Despite this, the terrain of Kazusa and Awa Province (in the south of modern Chiba) is difficult for military operations, and Hojo supply lines relied either on ships crossing Tokyo Bay, which was difficult even in good weather, or on taking the long way around through Musashi Province (modern Tokyo).

By certified, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=55415779

Neither of these options was particularly appealing, and what was more, the number of troops that the Hojo would have needed to commit to ending the war decisively would have left their other frontiers unacceptably vulnerable. So, in late 1577, a peace agreement (the Boso Ichiwa) was reached, establishing the border between the two factions and arranging a marriage to seal the deal.

Although the marriage would end within a few years, with the death of Ujimasa’s daughter, the peace held (more or less). This is demonstrated by the fact that when civil war broke out among the Satomi following Yoshihiro’s death in 1578, the Hojo did not intervene, even though it would have been to their advantage to do so. The peace would eventually come to an end in 1590, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Uesugi Kenshin, one of the Hojo’s most dangerous foes, also died in 1578, and Uesugi, much like the Satomi, quickly fell into infighting over who would succeed him. This time, the Hojo made some attempts to intervene, as Uesugi Kagetora, one of the candidates, was Ujimasa’s younger brother, who had been adopted by Kenshin as part of the earlier peace deal. Ujimasa’s support for his one-time brother seems to have been quite limited, however, as Hojo forces contented themselves with securing control over Kozuke Province before withdrawing.

Takeda Shingen had died in 1573, and with the Uesugi and Satomi tearing themselves apart over succession, by 1578, Ujimasa might have been forgiven for thinking that he’d ‘won’ in the Kanto. Unfortunately for him, Shingen’s death led to the disastrous Battle of Nagashino in 1575, in which the Takeda clan’s power was broken, leaving the western approaches to the Kanto open to a new, and far more dangerous, player.

Oda Nobunaga had risen from obscure origins in Owari Province (around modern Nagoya) to become the preeminent lord in the realm. Though his power was not yet completely unchallenged, by 1578, he was best placed to be the man who would unite the realm and end the Sengoku Jidai. With that in mind, Ujimasa reached out diplomatically, seeking to gain Nobunaga’s favour and perhaps arrange a marriage between the Oda and Hojo. Around this time, he also seems to have ‘retired’ and given control of the clan to his son, Ujinao, whilst in reality retaining actual power for himself.

For his part, Nobunaga seems to have had little interest in a rapprochement with the Hojo, though his exact plans aren’t clear; it’s reasonable to assume that, much like the Takeda, Nobunaga viewed the Hojo as a rival to eventually be crushed. However, in the short term, he had more pressing concerns in the West, dealing with the powerful Mori Clan, and for now, the Hojo were left alone.

With Nobunaga’s death in June 1582, everything changed. Taking advantage of the chaos, Ujimasa launched an attack against former Oda loyalists in the Kanto, securing control of the whole of Kozuke Province, and advancing into Kai, where he was met by another power seeking to take advantage of Nobunaga’s death, Tokugawa Ieyasu.

The fighting didn’t go well for the Hojo, but neither side was committed to all-out war, so a peace was agreed upon, which saw Ujimasa’s son, Ujinao, marry Ieyasu’s daughter, Tokuhime. In 1583, following the death of the last Ashikaga Kanto kubo, Ujimasa took the title for himself, positioning the Hojo at the very top of the hierarchy in the Kanto.

Not long after that, a successful campaign in support of allies in Shimotsuke Province brought the southern half of that province under his control, and Hojo territory reached its greatest extent. By some later estimates, the territory was valued at 2.4 Million Koku, and with control of several key rivers and coastal areas, the Hojo now dominated the political, military, and economic spheres within the Kanto.

In 1587, the chaos that had followed Nobunaga’s death had come to an end, with Toyotomi Hideyoshi emerging as the ultimate winner. That year, he issued the Soubujirei or “General Peace Order” commanding that all Daimyo cease private wars, essentially bringing an end to the Sengoku Jidai, at least on paper.

The Hojo agreed to abide by this order, but there was one outstanding issue. During the fighting in Kai Province in 1582, the Numata Domain, territory of the Sanada Clan, had defied Hojo attempts to conquer it. Though the fighting had largely come to an end, the border remained undefined, and so Hideyoshi dispatched vassals to settle the issue.

Hideyoshi’s decision was that two-thirds of the territory would go to the Hojo, and the remaining third would remain in Sanada hands. To confirm the arrangement, the powerful Numata Castle was handed over to the Hojo and peace was apparently agreed. However, shortly after this, the new lord of Numata arranged for the defection of nearby Nagurumi Castle, on the Sanada side of the border.

photo: Qurren (トーク) Taken with Canon PowerShot G9 X – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=63097035による

The plot succeeded, and Nagurumi was handed over to Hojo forces without a fight. The problem was that this was a clear violation of the peace deal, and things only got worse when Ujinao denied any knowledge of the plot in a letter to Hideyoshi, attempting to present the capture of the castle as a fait accompli.

Hideyoshi wasn’t about to accept that, and demanded that Ujimasa (retired, but still effective head of the clan) come to Kyoto to explain his clan’s actions.

Ujimasa refused, and Hideyoshi took this as an act of open rebellion. In 1589, he ordered all lords to attack the Hojo as punishment for their defiance. Initial attacks from the Sanada clan were repelled by Hojo forces, but Hideyoshi was able to muster a force in excess of 200,000 men, and when the main attack began, it would be a fight to the death.

The Odawara Campaign is deserving of a post of its own, I think, so we’ll leave it there for now.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8C%97%E6%9D%A1%E6%B0%8F%E6%94%BF

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B1%8A%E8%87%A3%E7%A7%80%E5%90%89

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B0%8F%E7%94%B0%E5%8E%9F%E5%BE%81%E4%BC%90

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%90%8D%E8%83%A1%E6%A1%83%E5%9F%8E

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%83%A3%E7%84%A1%E4%BA%8B%E4%BB%A4

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8C%97%E6%9D%A1%E6%B0%8F%E5%BA%B7