In June 1565, the powerful Miyoshi Clan launched a coup against the Shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiteru. In the Eiroku Incident (named for the era), the Miyoshi successfully killed Yoshiteru, and his brother, Yoshiaki, a rival claimant to the throne, fled the capital, seeking support from regional warlords.

Nobunaga was initially enthusiastic about supporting Yoshiaki and the Shogunate more generally. Sources aren’t clear about Nobunaga’s ambitions at this point, with some arguing he genuinely wanted to restore the Ashikaga, whilst others portray it as cynical politicking, with Nobunaga intending to replace the Miyoshi’s puppet Shogun with his own.

Regardless, in the short term, military defeat limited Nobunaga’s practical aid, and it wasn’t until September 1568 that he formally recognised Yoshiaki as Shogun and dispatched an army to Kyoto to secure his accession to the throne. There was some resistance, but Nobunaga’s forces would prove triumphant, and Ashikaga Yoshiaki was installed as the 15th (and final) Ashikaga Shogun. It seems that Yoshiaki wanted to install Nobunaga as kanrei, or deputy, but he refused. Moreover, at this point, the Kyoto political community seemed to have viewed Nobunaga as little more than Yoshiaki’s general, rather than a political force in his own right.

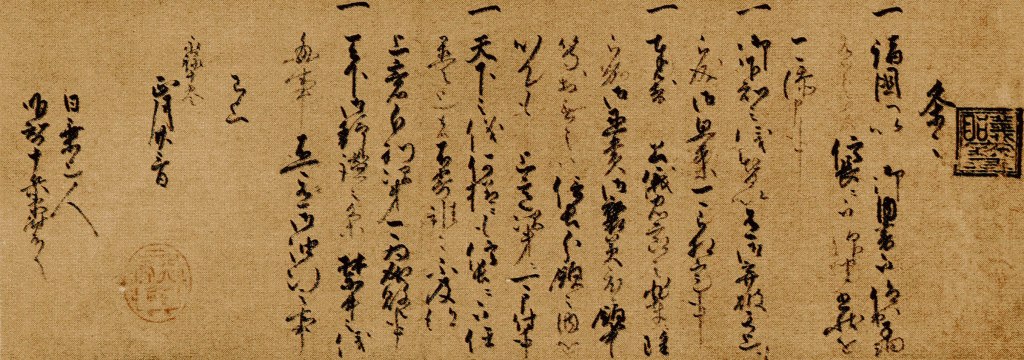

In early 1569, Nobunaga once again proved his worth to the Shogunate by putting down an attempt by the Miyoshi Clan to restore their position in the capital. Shortly after that, Nobunaga issued the denchuonokite, or “Rules of the Palace”, which were a set of nine (with seven more added later) rules for the management of the Shogun’s court. For a long time, it was believed that these rules were the first clear example of Nobunaga imposing his will on the Shogunate, though later research suggests that Yoshiaki agreed to the rules, and it was only later that the relationship between the two men began to break down.

Nobunaga seems to have intended to return to his own territories after the restoration, serving as a sort of enforcer for the Shogun. However, by this point, the Shogunate was at such a low ebb that he found himself obliged to become closely involved in the running of the government. It has been suggested that the issuing of the “Palace Rules” was part of wider efforts by Nobunaga to reinforce the Shogunate, whilst also reining in the tendency of the Shogun to use his remaining power arbitrarily, favouring his own supporters at the expense of powerful clans elsewhere, who, Nobunaga (rightly) worried, would then become enemies of the Shogun, and be extension, himself.

It was not as though Nobunaga had any trouble finding enemies of his own. In the late 1560s, his forces invaded Ise Province, and in 1570, he led an army north to Wakasa Province to subjugate the Asakura Clan, who had defied him. The invasion went well, but when word reached Nobunaga that the Azai Clan, led by his brother-in-law, had betrayed him, he was forced to retreat.

The reasons for this sudden betrayal have been much romanticised, with Azai Nagamasa sometimes portrayed as a principled opponent of Nobunaga’s tyranny, or else bound by a close alliance to the Asakura that trumped his loyalty to the Oda. Historians are still divided on the exact cause, but the betrayal was likely a combination of opportunism and genuine fear about Nobunaga’s intentions.

Nobunaga’s army was defeated at the Battle of Kanegasaki, with Nobunaga himself forced to flee the field. It is said that he was only able to escape because of the rearguard action led by Kinoshita Tōkichirō, who would later be known as Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and who was rewarded with gold by Nobunaga upon his return to Kyoto.

Sources disagree on exactly how severe the defeat was; some state that Nobunaga returned to Kyoto with just ten men, whilst others put his army’s losses at fewer than 1300, out of a total of 30,000. Both numbers may be true, and it would certainly explain why Nobunaga himself seems to have remained calm in the wake of the defeat, inspecting the Imperial Palace the day after he returned to Kyoto.

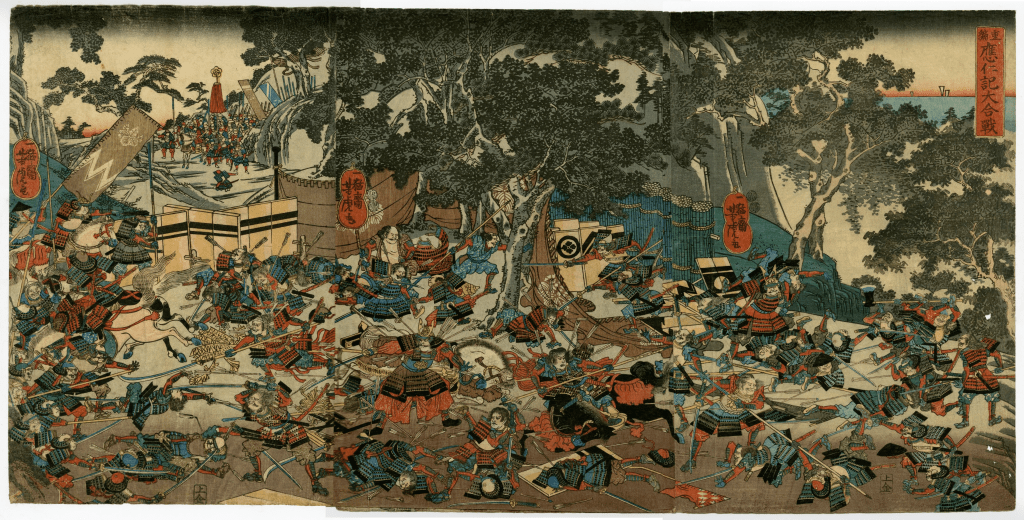

Whilst Nobunaga had certainly been forced to retreat, the case for his army remaining largely intact is made by the fact that just a few months after Kanegasaki, he, along with his ally, Tokugawa Ieyasu, led a force of up to 40,000 men in a campaign against the Azai-Asakura, culminating in the Battle of Anegawa, which Nobunaga won, though he was unable to finish either the Azai or Asakura off, despite inflicting heavy casualties on both.

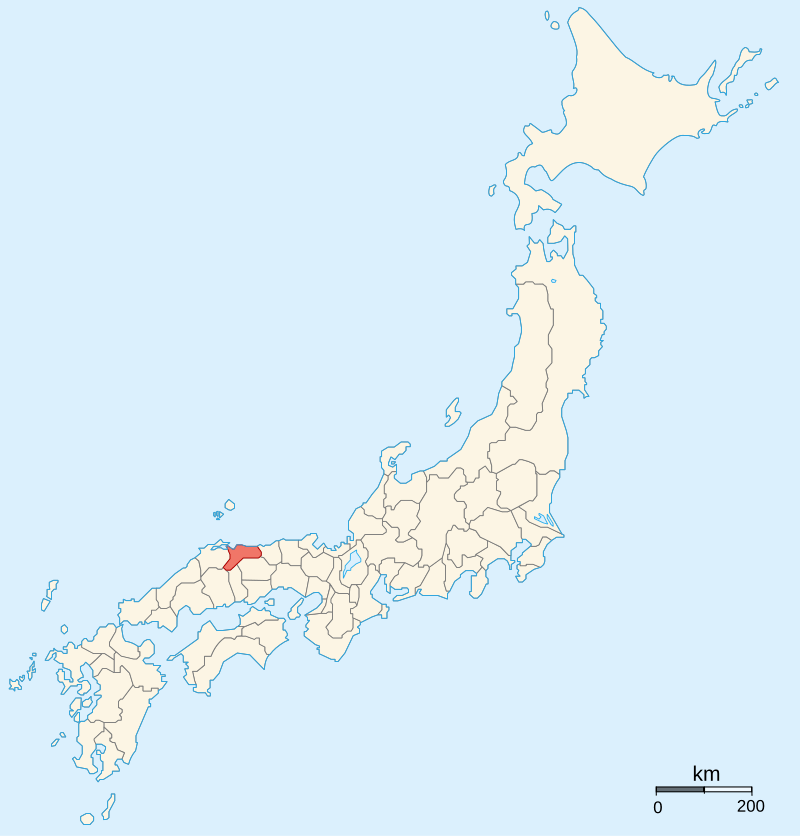

Nobunaga was prevented from pressing his advantage by events elsewhere. In August, the Miyoshi raised an army in Settsu Province (modern Osaka). Around the same time, the Ishiyama Hongan-ji Temple (on the site of modern Osaka Castle), fearing Nobunaga’s expansionist ambitions, raised an army of its own.

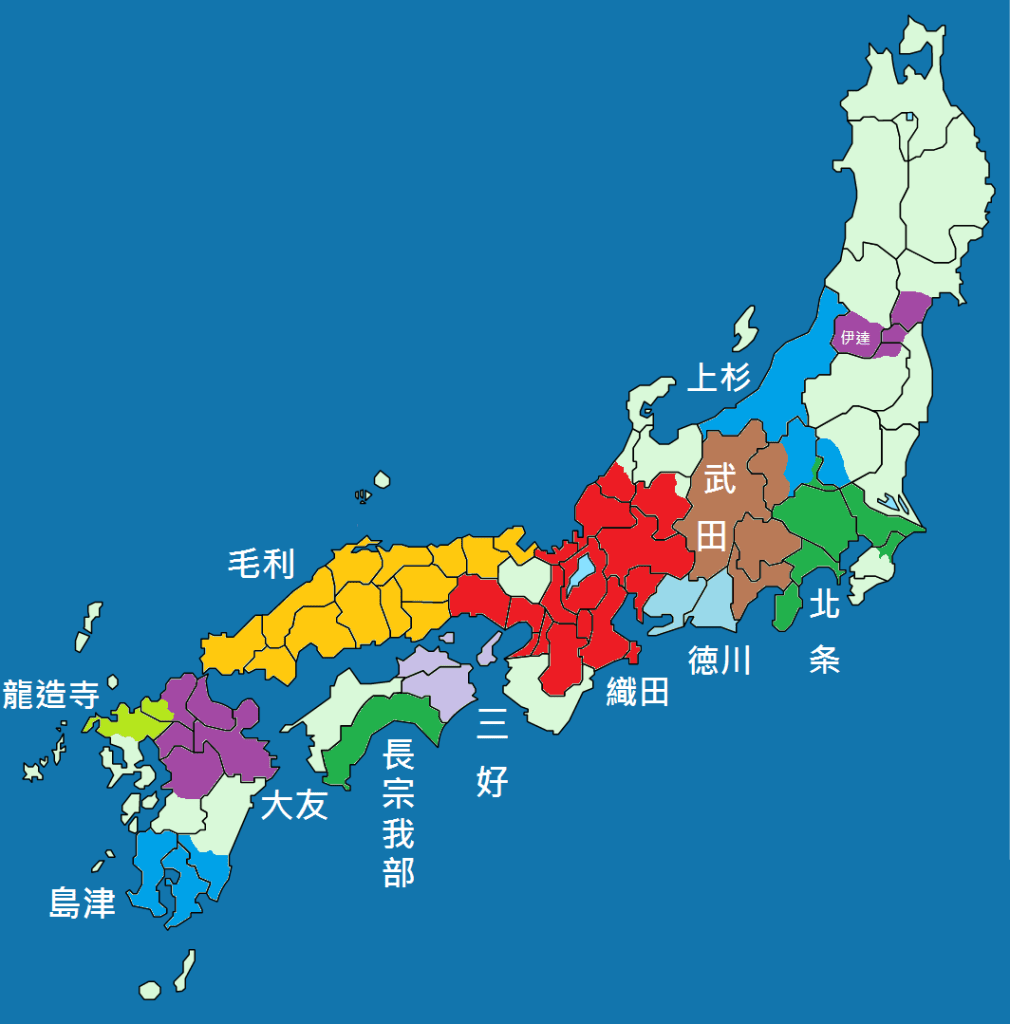

By Takafuji – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=77306876

All this was combined with the ongoing conflict with the Azai-Asakura alliance, and in September, supporters of Ishiyama Hongan-ji launched a rebellion in Ise Province in which Nobunaga’s younger brother, Nobuoki, was killed (or forced to commit seppuku) Faced with all this, Nobunaga chose to leverage his power at court, and in December, an Imperial decree was issued, ordering all sides to stop fighting, which they duly did, saving Nobunaga in the short-term.

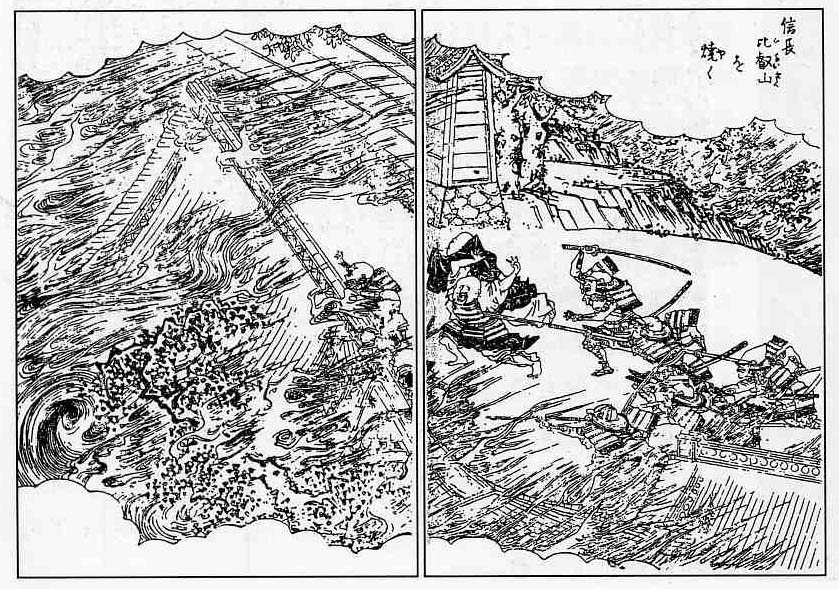

Peace in the Age of the Country at War was only ever a fleeting thing, however. In February 1571, Nobunaga led an army of some 50,000 against the forces of Ishiyama Hongan-ji, resulting in one of his most controversial acts, the burning of Mt Hiei.

Mt Hiei is one of the most sacred sites in Japanese Buddhism, and in the late 16th Century, its monks were major political players in their own right, with influence at both the Imperial and Shogunate court, and an army of warrior monks to defend their interests. Nobunaga’s attack should be seen in this context, but it was also an incredibly shocking act, which outraged a Japanese political class that took its religion very seriously. One particularly outraged player was Takeda Shingen, who denounced Nobunaga and began a campaign against his ally, the Tokugawa.

Whilst historians suggest that Shingen’s outrage over Mt Hiei was just a pretext, the invasion of the Tokugawa home province of Mikawa was a serious threat to Nobunaga’s position. Shingen was arguably the most formidable warlord of his time, and may well have proved more than a match for Nobunaga. He was certainly too much for Tokugawa Ieyasu, who was obliged to retreat and call on Nobunaga for help.

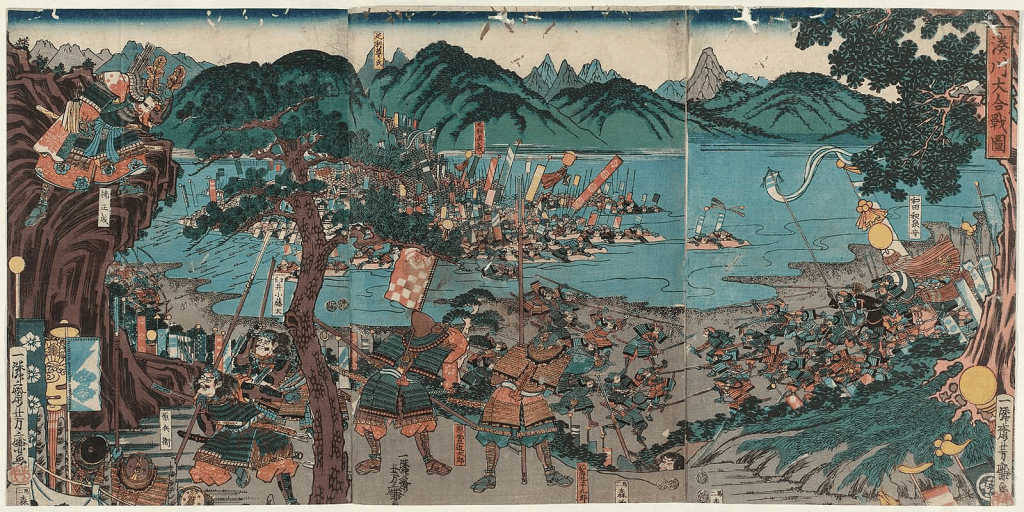

Nobunaga dispatched a force of 3000 men to help, but they, along with the Tokugawa, were decisively defeated at the Battle of Mikatagahara in January 1573. Ieyasu himself barely managed to escape the disaster. In the aftermath, Nobunaga appeared vulnerable, so vulnerable that Ashikaga Yoshiaki, who had begun to chafe under Nobunaga’s regime, raised an army in opposition to him, presumably in the hope that Takeda Shingen was on his way.

Unfortunately for Yoshiaki, Shingen was dead. Though the circumstances of his death are still murky, it ended a serious threat to Nobunaga, perhaps the most serious threat, and he was able to focus his forces on Kyoto, where he swiftly forced Yoshiaki to make peace and resume his position firmly under Nobunaga’s thumb.

Yoshiaski refused to learn his lesson, however, and a second rebellion broke out not long after, with Shogunate loyalists barricading themselves inside Makishima Castle, which Nobunaga swiftly took, sending Yoshiaki into exile, and effectively bringing an end to the Ashikaga Shogunate, once and for all. Historians debate whether the Shogunate actually ended at this time, as Yoshiaki continued to use the title, and would spend the next few years roaming Japan seeking support to overthrow Nobunaga.

What is true, though, is that the Ashikaga, long in decline, would never rule from Kyoto again. There had been strongmen before, of course, but they had always ruled through puppet Shoguns, and the institution had remained largely intact. Nobunaga did away with that; though he would never take the title of Shogun for himself, from 1573 until his death, Nobunaga sat at the top of a very precarious pile.

By Alvin Lee – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39200929

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%B9%94%E7%94%B0%E4%BF%A1%E9%95%B7

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%89%E6%96%B9%E3%83%B6%E5%8E%9F%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AF%94%E5%8F%A1%E5%B1%B1%E7%84%BC%E3%81%8D%E8%A8%8E%E3%81%A1_(1571%E5%B9%B4)

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%B9%94%E7%94%B0%E4%BF%A1%E8%88%88

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%95%B7%E5%B3%B6%E4%B8%80%E5%90%91%E4%B8%80%E6%8F%86

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%BF%97%E8%B3%80%E3%81%AE%E9%99%A3

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A7%89%E5%B7%9D%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%87%91%E3%83%B6%E5%B4%8E%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84#%E6%88%A6%E5%BE%8C

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B1%8A%E8%87%A3%E7%A7%80%E5%90%89

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%B5%85%E4%BA%95%E9%95%B7%E6%94%BF

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AE%BF%E4%B8%AD%E5%BE%A1%E6%8E%9F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E6%98%AD

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%9C%AC%E5%9C%80%E5%AF%BA%E3%81%AE%E5%A4%89

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%B0%B8%E7%A6%84%E3%81%AE%E5%A4%89

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%89%E5%A5%BD%E7%BE%A9%E7%B6%99

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E6%A0%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%89%E5%A5%BD%E4%B8%89%E4%BA%BA%E8%A1%86

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ishiyama_Hongan-ji