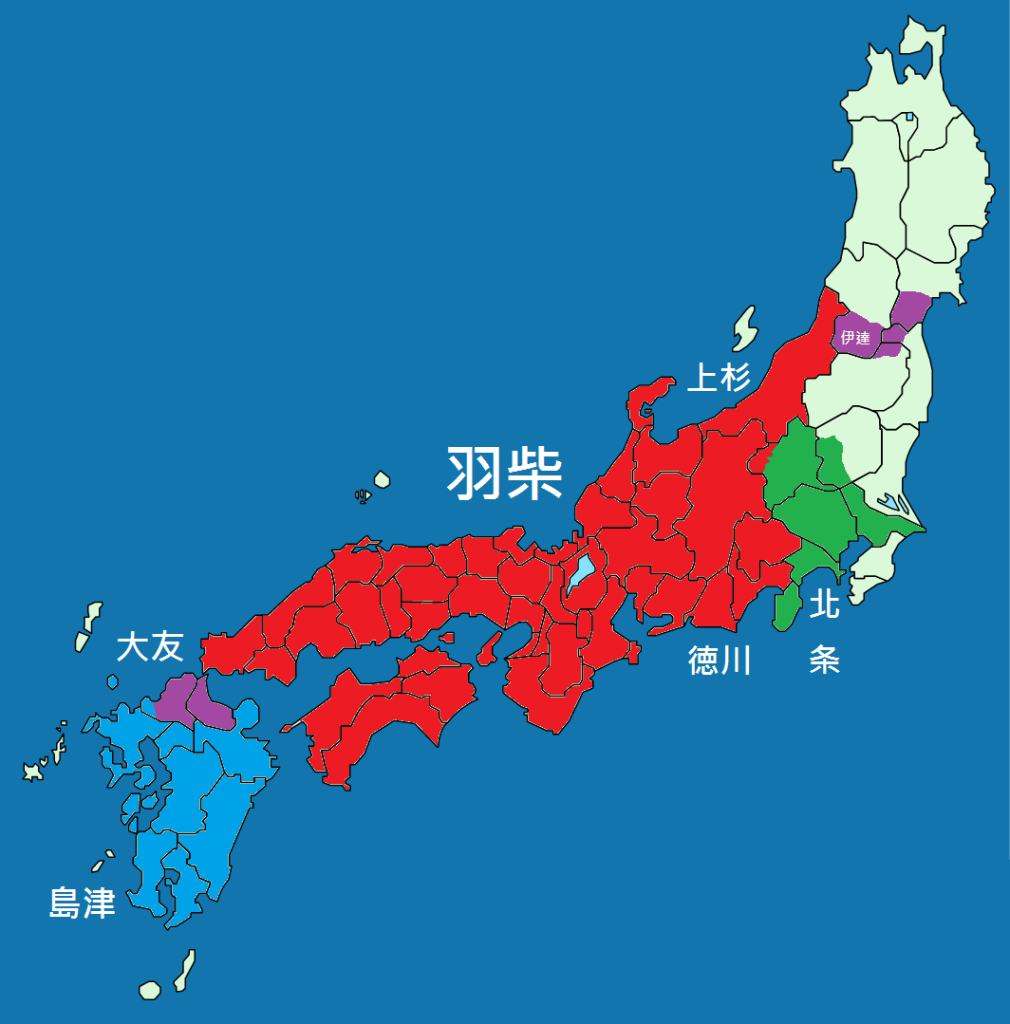

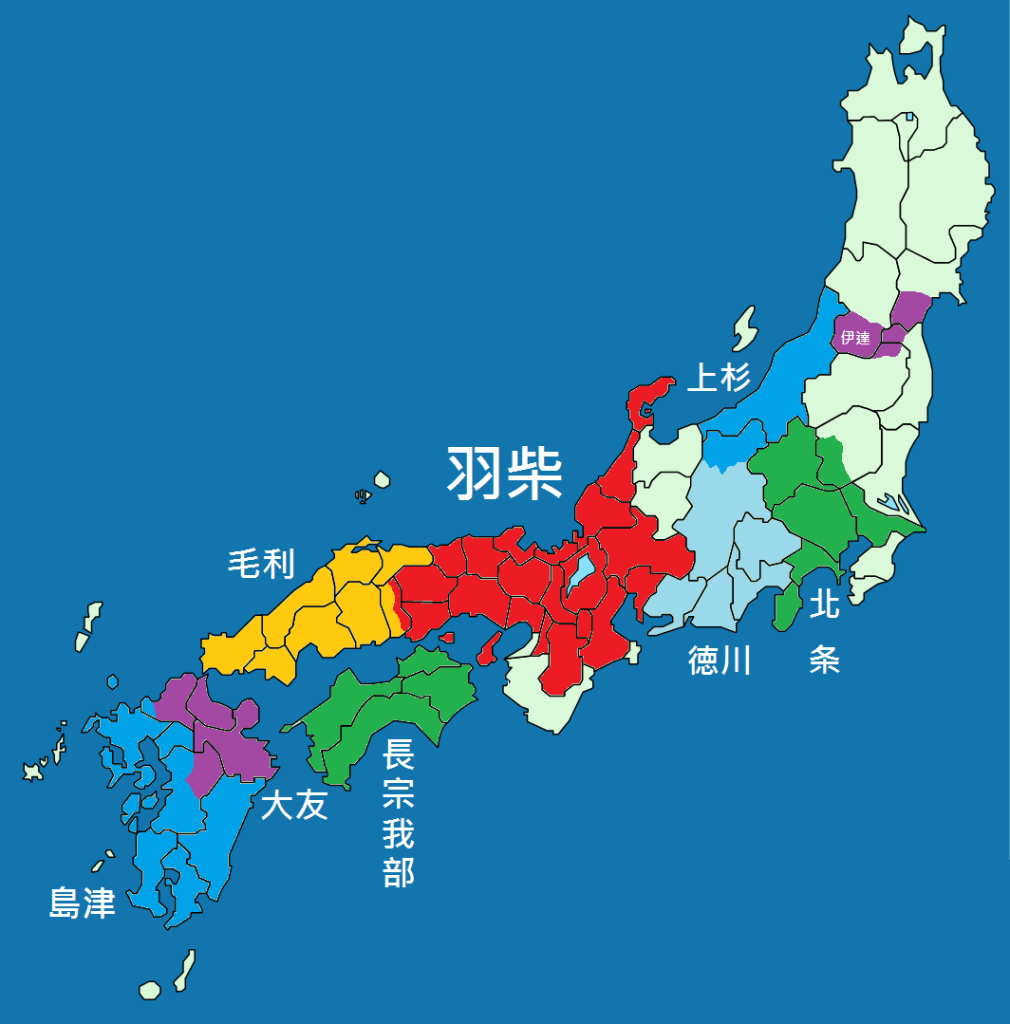

Last time, we looked at how Date Masamune defied an order from Toyotomi Hideyoshi to end his local wars. In 1590, the Date were summoned to take part in the upcoming campaign against the Hojo, based at Odawara, and Masamune knew better than to push his luck. Hideyoshi, however, had not forgotten his earlier defiance.

When Masamune arrived at Odawara, he was stripped of all the territory he had taken in Aizu and confined to the 13 counties in Mutsu and Dewa Provinces that the Date had controlled before the peace order, obliging Masamune to leave the recently conquered Kurokawa Castle and return to his family’s seat at Yonezawa. In 1591, a rebellion broke out in Masamune’s home province, and after he put it down, letters were ‘found’ that implicated Masamune in instigating the violence.

The rumours reached Hideyoshi in Kyoto, and he ordered Masamune to come in person to explain himself, which he promptly did, eventually being pardoned, but having his territory reduced still further. Despite the fact that Masamune then fought in Hideyoshi’s invasion of Korea, it wasn’t long before further rumours of treason surrounded him.

In 1595, Hideyoshi’s nephew, Hidetsugu, was accused of treason, allegedly plotting either to overthrow his uncle or else usurp the regency after his death. Even at the time, the accusations were considered dubious, and the exact reasons are still murky today, but Hidetsugu was obliged to commit seppuku, and 39 members of his family and household were purged (read, murdered).

The brutality of the crackdown and the somewhat flimsy evidence would eventually backfire for Hideyoshi, but for now, we can focus on how this purge would eventually involve Masamune. He and Hidetsugu had enjoyed a close relationship, and when accusations of treason were being thrown around, it didn’t take long for people to point that out.

Masamune was summoned to explain himself once again. He had good reason to worry; his cousin had been Hidetsugu’s concubine (and had died in the purge), and it was widely thought that Hideyoshi believed that Masamune was guilty. In the end, a combination of Masamune’s eloquent denial and the intervention of several influential retainers led to his pardon. He was, however, obliged to sign a document, witnessed (and potentially enforced) by 19 powerful vassals, stating that if he were ever to commit treason, his position as head of his clan would be forfeit.

Hideyoshi died in 1598, leaving his young son in the care of a council of five regents. Masamune was not on this council, but he quickly reached an understanding with Tokugawa Ieyasu, arguably the council’s most powerful member. In 1599, Masamune’s daughter married Ieyasu’s fifth son, something that was believed to be an example of Ieyasu securing illegal alliances, though modern scholars suggest that this is an example of a violation of the ‘spirit’ rather than the letter of the law.

By 1600, it had become clear that the Council of Regents was not going to last, and a new conflict swiftly broke out. Ieyasu secured the support of Masamune by promising to restore all the lands he had lost in 1590. Date forces would not be present at the decisive Battle of Sekigahara, however, and despite some successes against Ieyasu’s enemies in the north, an attempt to retake the promised territories by force was ultimately unsuccessful.

Despite this, Masamune still petitioned Ieyasu for the return of the territory, which Ieyasu refused to do, and in fact, Date lands were reduced further (though they would remain the fifth richest clan by koku (rice production)). In 1601, Masamune moved his headquarters to Sendai, establishing the Sendai Domain, which would continue to be the centre of the Date Clan for the next 250 years.

Though distant from the capital and never entirely trusted, Masamune would play a significant role in Japan’s future. In 1613, he ordered the construction of a European-style galleon, the San Juan Bautista. Masamune was the only Daimyo to receive permission from the Tokugawa to send missions overseas to represent Japan. The so-called Keicho Embassy departed Japan in October 1613, travelling across the Pacific to New Spain (modern Mexico) and from there, across the Atlantic to Europe. The embassy would receive an audience with the King of Spain in January 1615, and then one with the Pope in October of the same year. The Embassy would not return to Japan until 1620, by which time Christianity had been outlawed by the Shogunate, meaning that the Ambassador and anyone involved had come under suspicion.

Meanwhile, Masamune at the Date had continued to support the new Shogunate, taking part in both Sieges of Osaka in 1614-15. However, once again, Masamune would find himself under attack by rumours of treason, this time after a supposed ‘friendly fire’ incident, in which Date troops fired on their allies. It’s not clear from surviving records if this incident actually happened, but in 1616, the rumour spread that Ieyasu planned to march against the Date.

When the two men met in early 1616, Masamune was cleared of any suspicion, and after Ieyasu passed away in June of that year, any serious suggestion that the Date and Tokugawa would go to war seems to have died out (though later texts suggest that Masamune had a plan to fight the Shogunate, should it come down to it)

With the age of constant civil war coming to an end, Masamune focused on developing his home territory. He ordered the construction of a canal that became the Teizan Canal (though it wouldn’t take its final form until the 19th century). He established a port at Ishinomaki, which was heavily damaged in a tsunami in 2011, and has since been largely rebuilt.

He also developed agriculture in the Kitakami River basin, which remains a major rice producer to this day. In the Edo Period, the Sendai Domain was valued at around 620,000 koku, but produced in excess of 745,000 koku annually, indicating how effective Masamune’s investments had been, and how inefficient Japanese land valuation was in the pre-modern period.

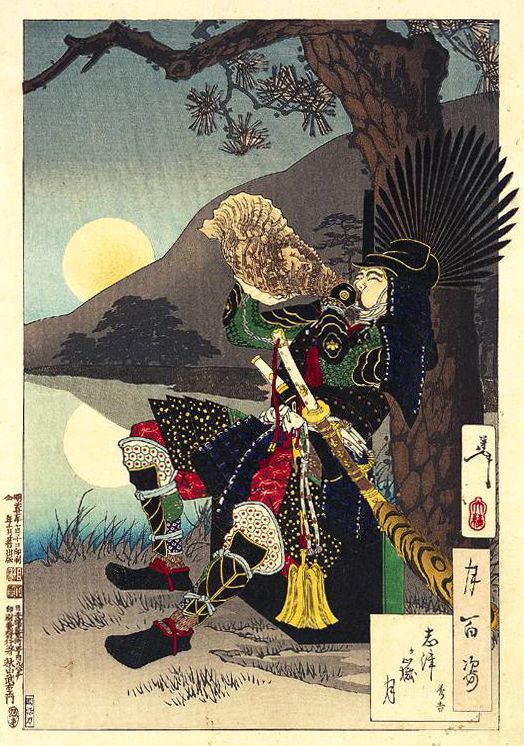

In his later years, Masamune would establish a warmer relationship with the Shogunate than he had known previously. When the third Shogun, Iemitsu, began to rule in his own right in 1632, he was said to have idolised Masamune, who by then was one of the last remaining Daimyo to have actually fought during the Sengoku period. The Shogun is said to have frequently asked Masamune for stories of the period, especially the battles he had fought, and what it had been like to serve Ieyasu and Hideyoshi (both of whom were legendary figures by that point)

Masamune remained vigorous until late in life, but in 1634, he began to develop serious health problems, and his condition declined quickly before he eventually passed away in June 1636. His death was mourned in Edo, with the Shogun banning revelry, fishing, and even the playing of music for seven days afterwards.

663highland 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2631054による

Masamune’s reforms and investments had left the Date in a strong financial position, and the Clan would often be treated generally by the Shogunate, with the clan being one of the few ‘outside’ Daimyo (a clan that had not been a vassal of the Tokugawa before Sekigahara) who was granted a marriage into the Shogun’s family.

Despite, or perhaps because of this, the third Lord, Tsunamune (Masamune’s grandson), proved to be something of a “rich kid” spending his days engaged in what is politely called “debauchery”. Although a certain amount of wine, women (or men), and song was expected of a Daimyo, Tsunamune was extreme to the point that his retainers tried to get rid of him. In August 1660, they petitioned the Shogunate directly, asking that Tsunamune be removed.

The Shogunate agreed, replacing Tsunamune with his two-year-old son, Tsunamura. Given his young age, Tsunamura needed a regent, and what followed was a decade of violence as rival factions sought influence over the young Lord. Finally, in 1671, a meeting was called in the house of Sakai Tadakiyo, a roju (senior minister) in Edo.

What was supposed to be a peaceful meeting to seek a solution to the ongoing violence in Sendai quickly turned into a bloody brawl, and by the end of it, swords had been drawn, and several men lay dead. Tsunamune, as a child, was not held responsible, but the families of those responsible for the bloodshed were executed in turn (in line with the law at the time).

As the Edo Period went on, the Sendai Domain, much like many Samurai holdings, began to suffer economic hardship. The problem was that the value of the land was estimated based on rice production in the 17th century, and by the early 19th century, those numbers simply didn’t add up.

Financial problems didn’t stop the Date from remaining loyal to the Tokugawa; during the Boshin War in 1868-69, the Sendai Domain was central to the Shogunate’s efforts to retain power. The Shogunate would ultimately lose the war, and the Date had their lands confiscated, though they were partially restored in the peace that followed. With the abolition of the domains, the Date joined the new aristocracy and continued to serve the new Meiji regime into the 20th century.

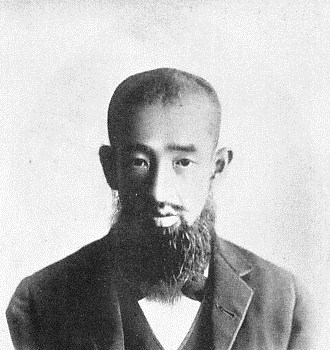

The Date were not always on the right side of the law, however. One infamous member of the clan was Junnosuke, who was known for carrying a knife to school and, in 1909, was sentenced to 12 years in prison for shooting a fellow student during a brawl. His sentence was eventually suspended when his lawyer ‘proved’ it was self-defence. In 1916, he left Japan for Manchuria (not yet under Japanese rule at that point), where he joined the Manchurian Independence Movement.

He had a varied career after this, serving in the Border Guards in Korea (then under Japanese control), but in 1923, he seems to have been operating as little more than a bandit in and around the Shandong Peninsula. In 1931, he became a naturalised Chinese citizen, but in 1937, he was at the head of some 4000 soldiers from Manchukuo and took part in the Japanese invasion of China; however, his unit was disbanded in 1939. After the war, he was caught by the Chinese, tried as a war criminal, and shot in 1948, bringing a violent career to a violent end.

In the interest of ending things on a lighter note, another descendant of the Date clan (a branch of it, anyway) is Date Mikio, one half of the famous comedy duo Sandwichman, who have won many awards and are arguably one of Japan’s most prolific duos, so that’s nice.

The main branch of the Date Clan survives into the modern era as well, with the current head, Date Yasumune, serving as a curator of the Zuihoden Museum, burial place of Date Masamune, and a repository for numerous artefacts related to the clan.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E9%A8%92%E5%8B%95

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Date_S%C5%8Dd%C5%8D

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%96%B0%E7%99%BA%E7%94%B0%E9%87%8D%E5%AE%B6

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Date_Masamune

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tokugawa_Ieyasu

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E7%B6%B1%E5%AE%97

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%9A%E6%B4%A5

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BA%8C%E6%9C%AC%E6%9D%BE%E5%9F%8E

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%8B%A5%E6%9D%BE%E5%9F%8E

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%91%BA%E4%B8%8A%E5%8E%9F%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B1%8A%E8%87%A3%E7%A7%80%E6%AC%A1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%82%B5%E3%83%B3%E3%83%BB%E3%83%95%E3%82%A1%E3%83%B3%E3%83%BB%E3%83%90%E3%82%A6%E3%83%86%E3%82%A3%E3%82%B9%E3%82%BF%E5%8F%B7

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BB%99%E5%8F%B0%E8%97%A9

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%85%B6%E9%95%B7%E9%81%A3%E6%AC%A7%E4%BD%BF%E7%AF%80

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%9F%B3%E5%B7%BB%E6%B8%AF

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B2%9E%E5%B1%B1%E9%81%8B%E6%B2%B3

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E6%94%BF%E5%AE%97

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E9%A0%86%E4%B9%8B%E5%8A%A9

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E6%B3%B0%E5%AE%97

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%82%B5%E3%83%B3%E3%83%89%E3%82%A6%E3%82%A3%E3%83%83%E3%83%81%E3%83%9E%E3%83%B3_(%E3%81%8A%E7%AC%91%E3%81%84%E3%82%B3%E3%83%B3%E3%83%93)

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BC%8A%E9%81%94%E5%AE%97%E5%9F%BA