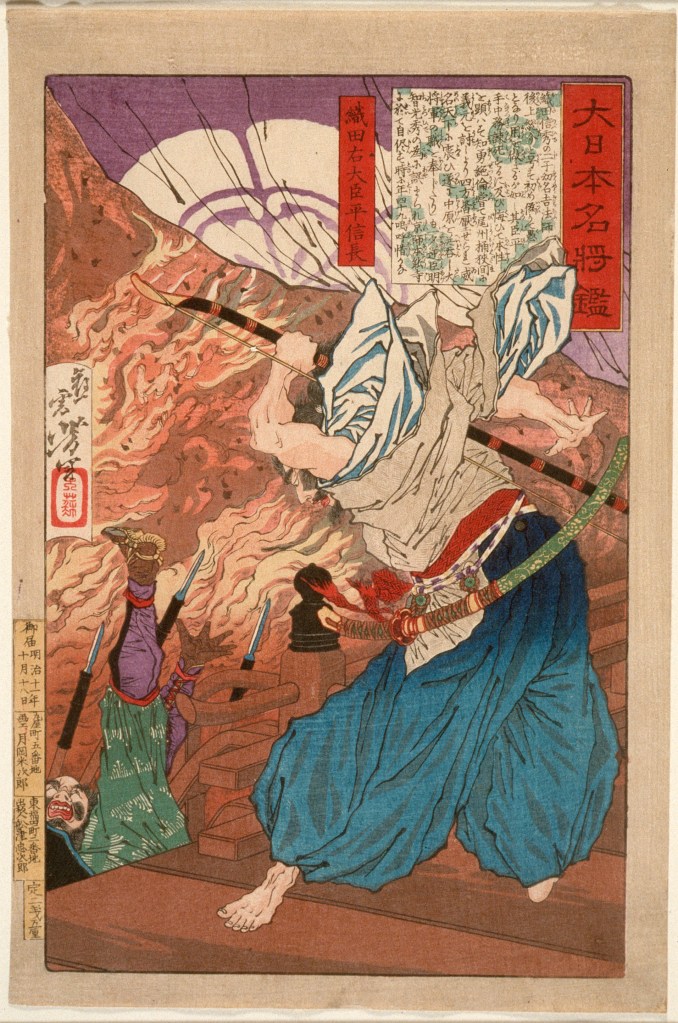

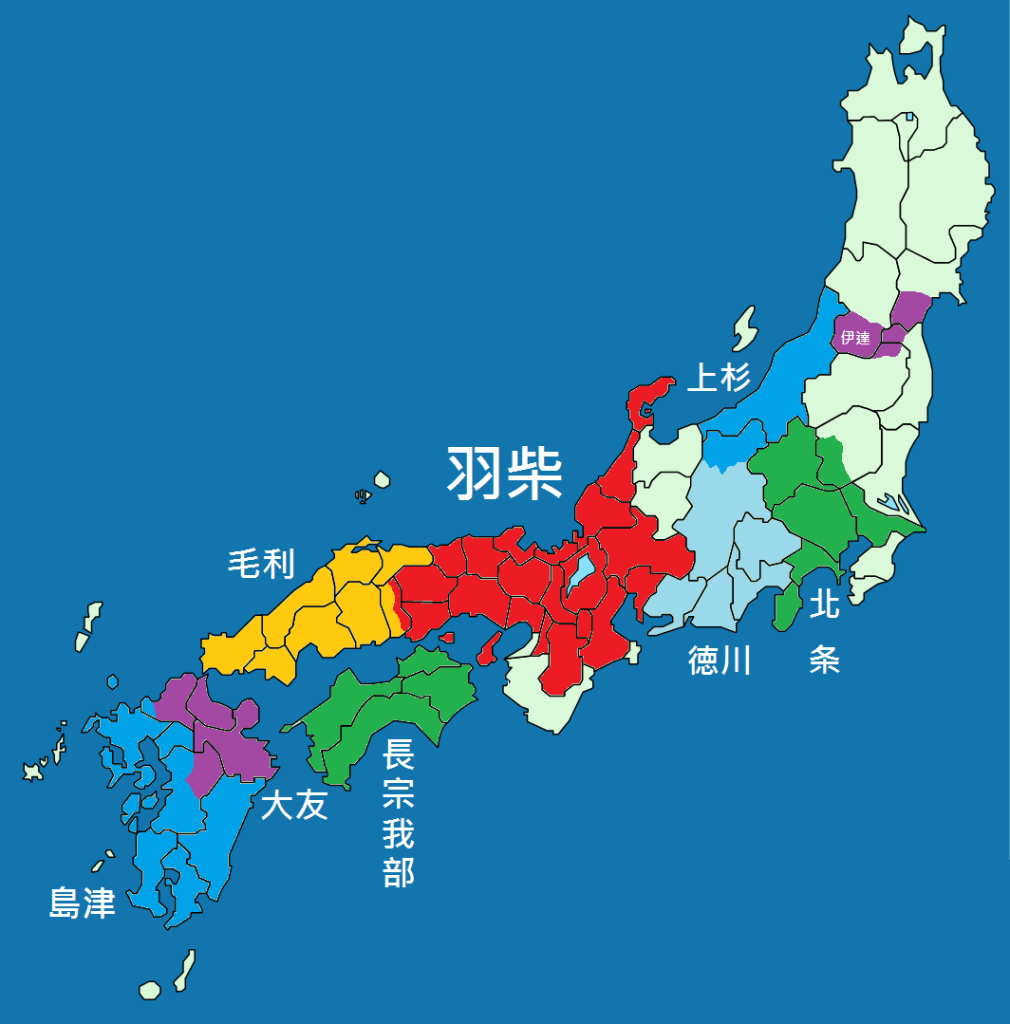

In 1577, a dispute between Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Shibata Katsuie led to Hideyoshi taking his army home, and leaving Katsuie to battle the mighty Uesugi Kenshin alone, a battle he lost. In the aftermath, Hideyoshi had every reason to fear the wrath of his master, Oda Nobunaga, and he was arguably lucky to keep his head, let alone his position.

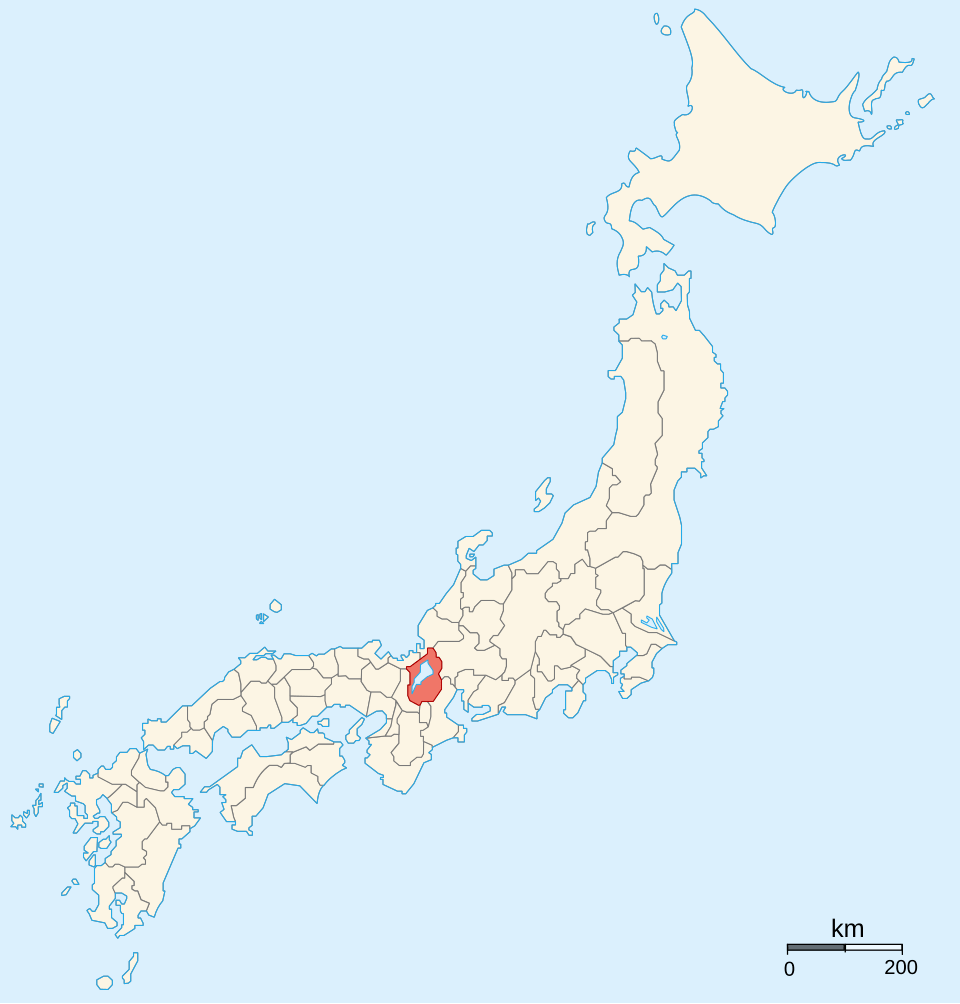

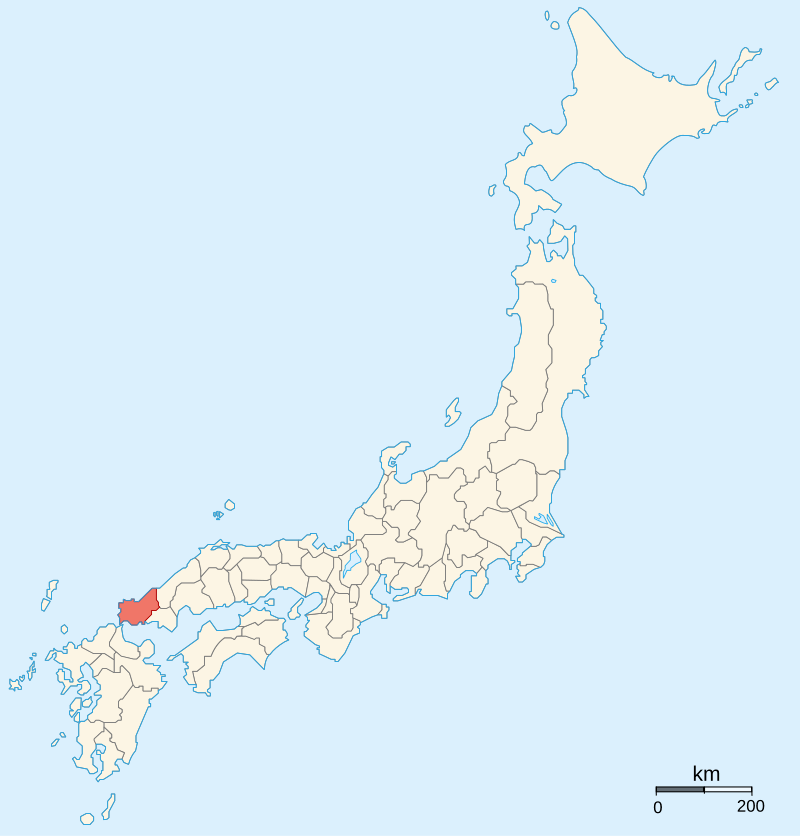

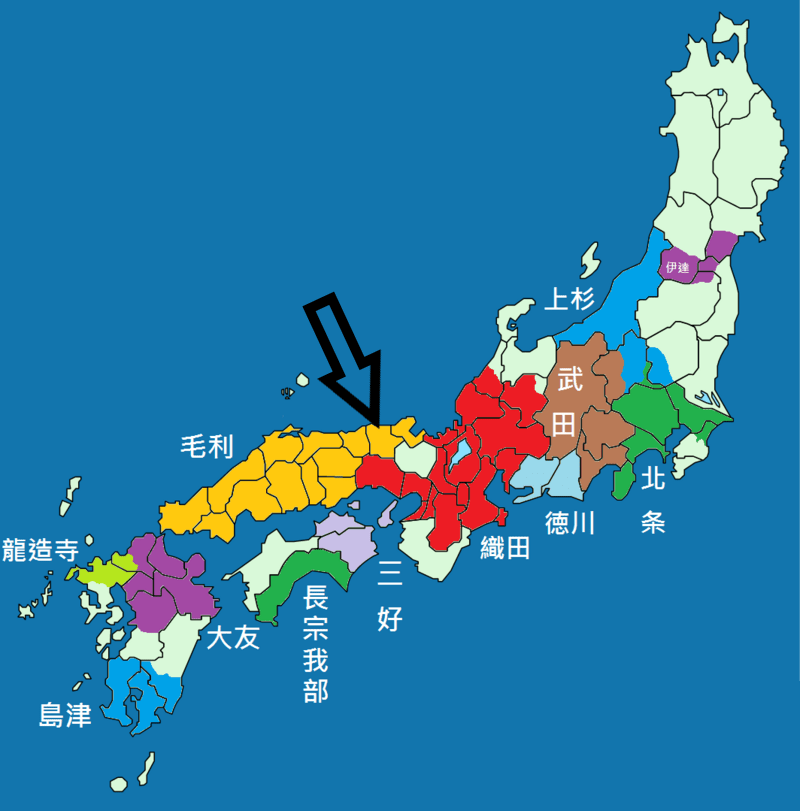

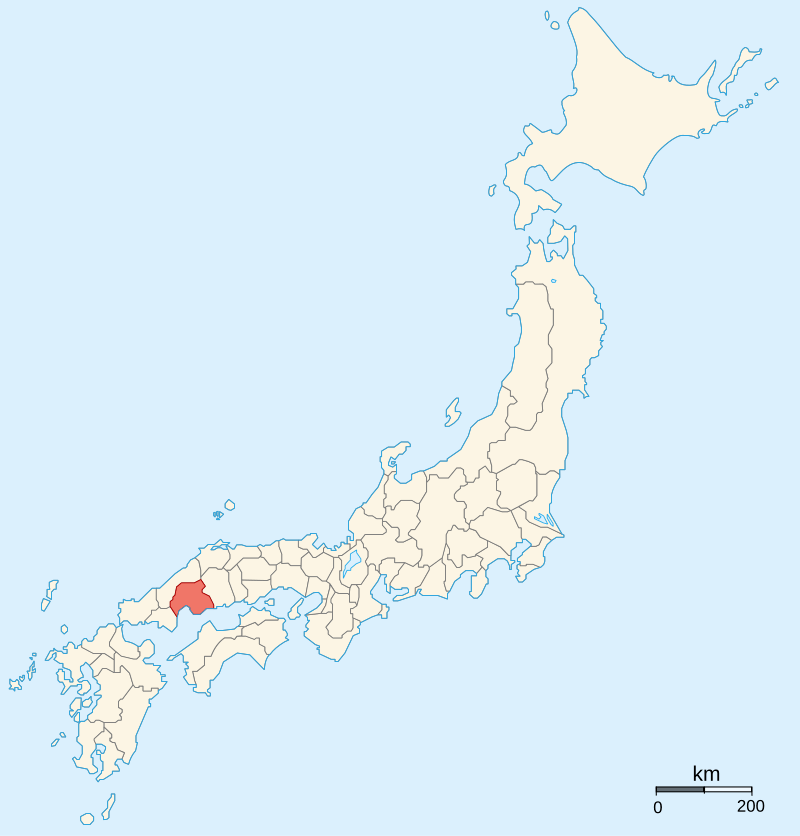

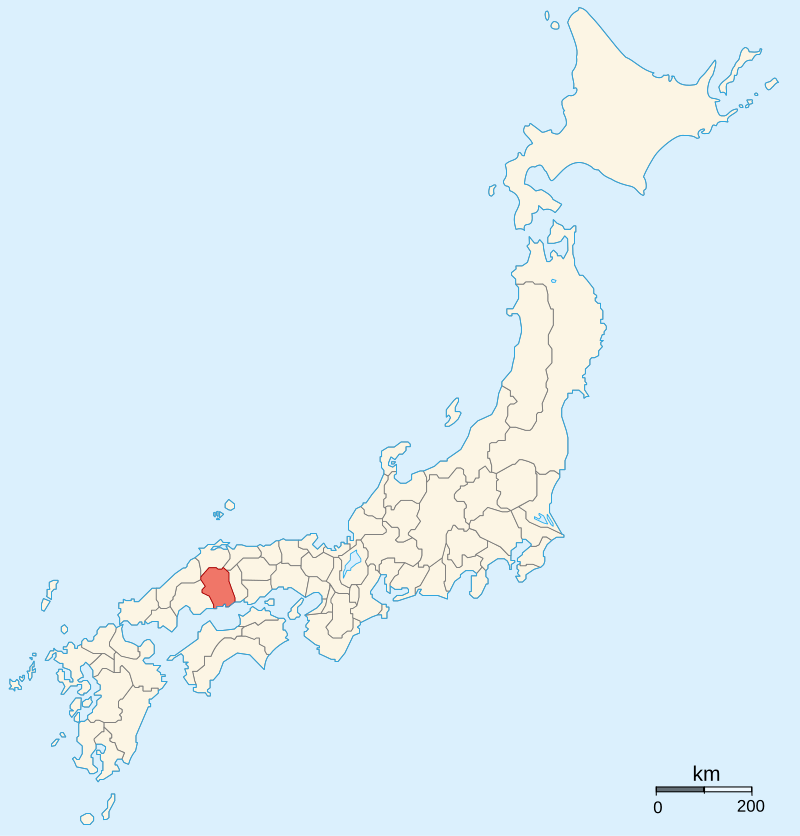

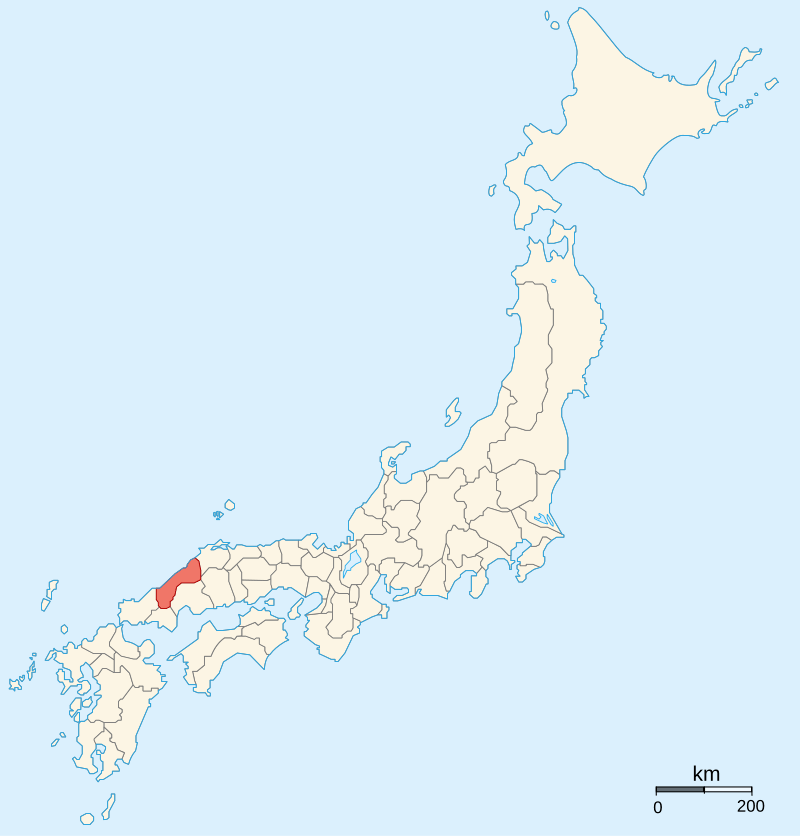

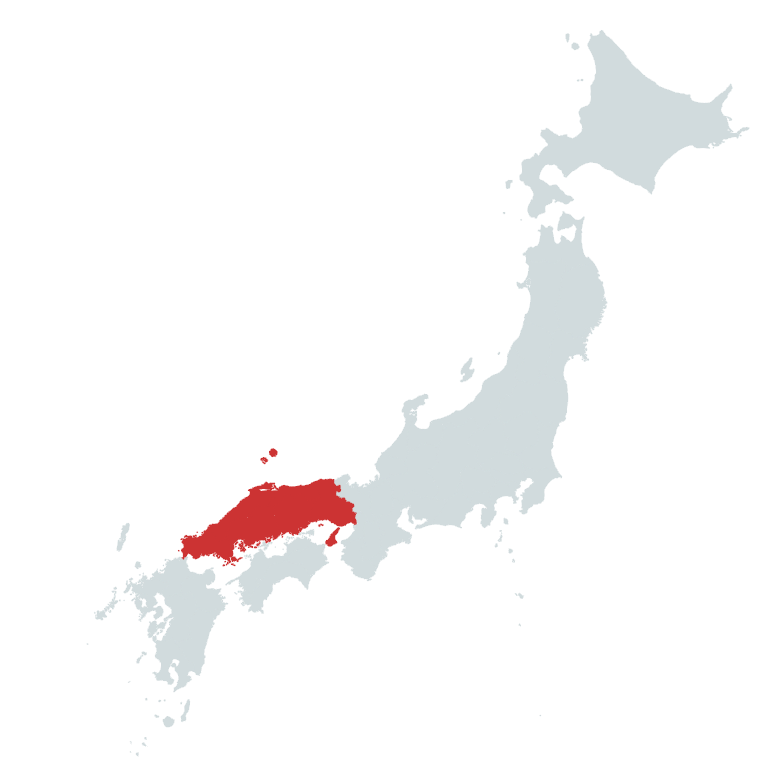

Nobunaga was well known for his ferocity, but he recognised capable subordinates. Hideyoshi had been reckless, but he had also earned a reputation as a good administrator and leader of men, and it wasn’t long before he was back in the Great Lord’s good books. In late 1577, he was dispatched west to contend with the powerful Mori Clan and by the end of the year, he was in control of Harima Province and advancing into neighbouring Tajima.

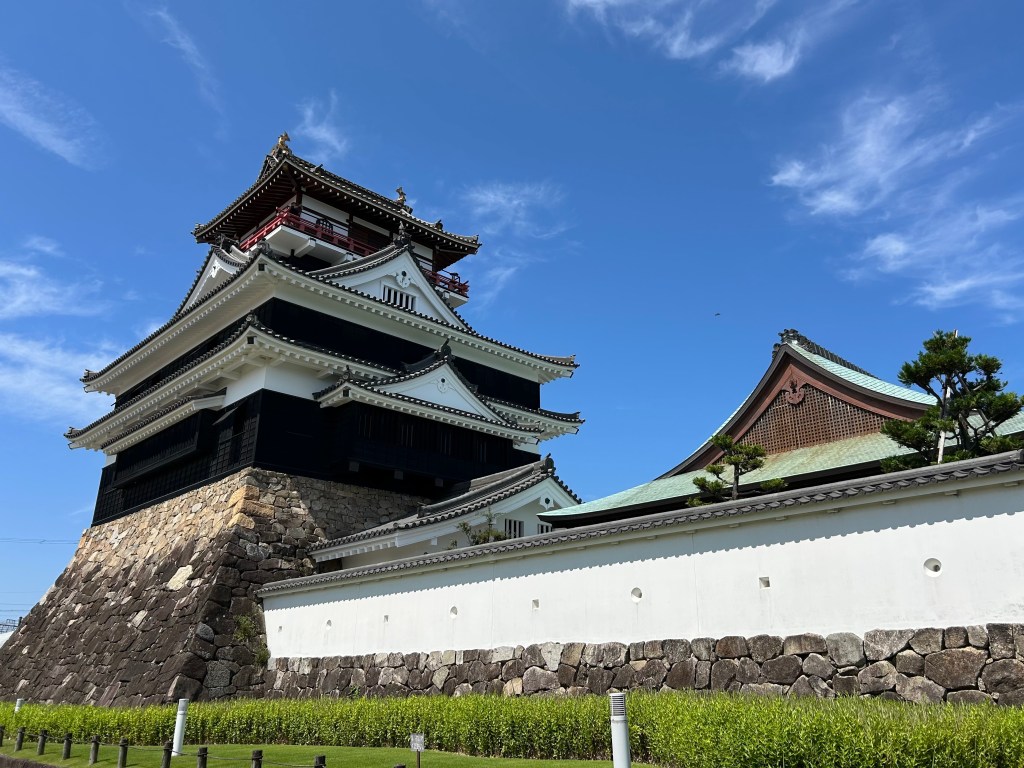

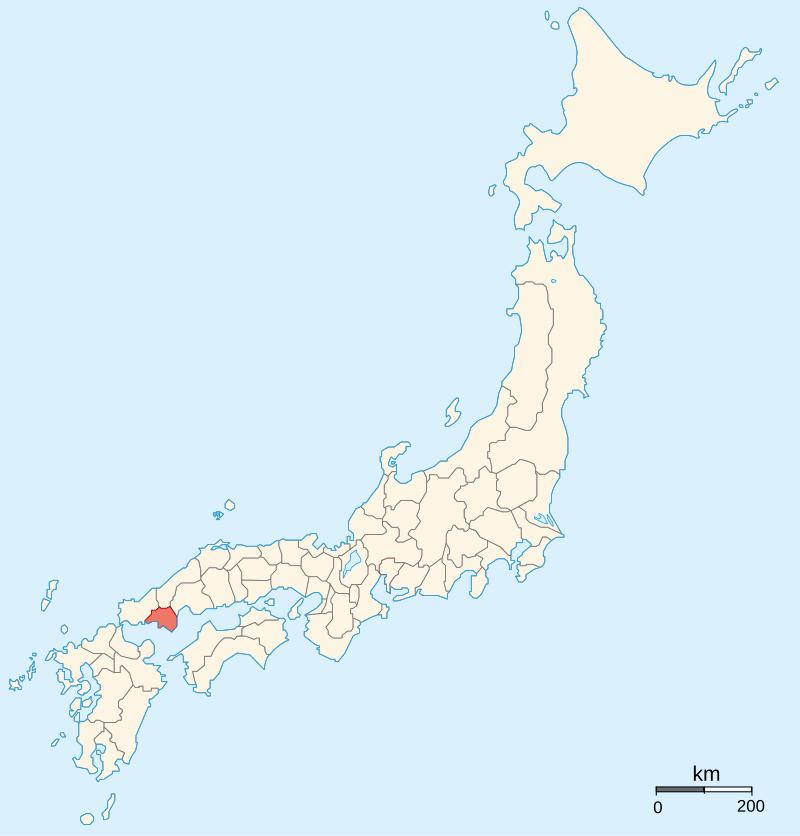

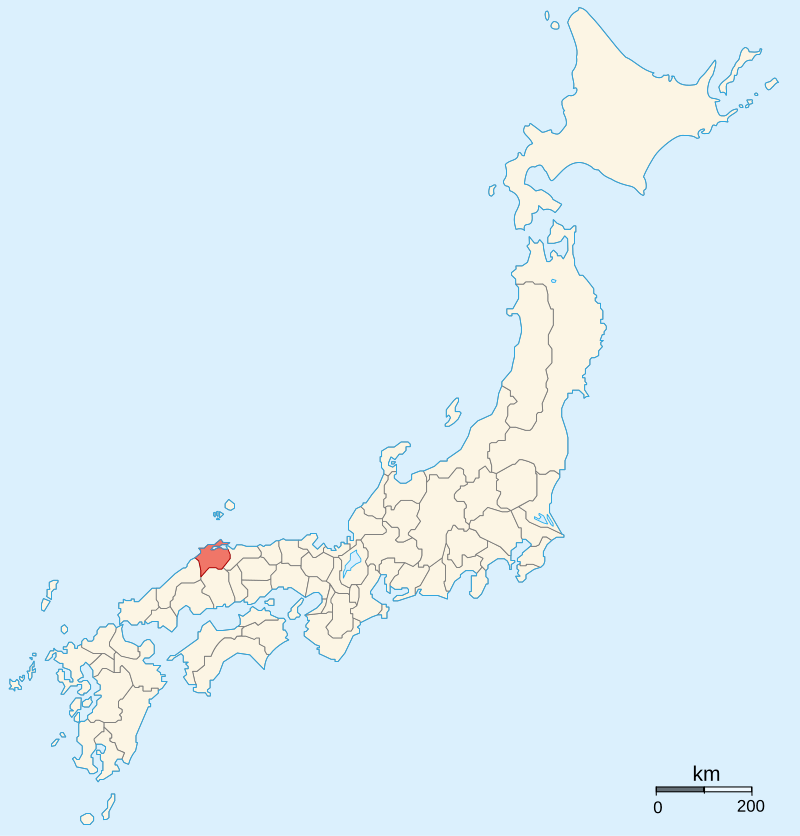

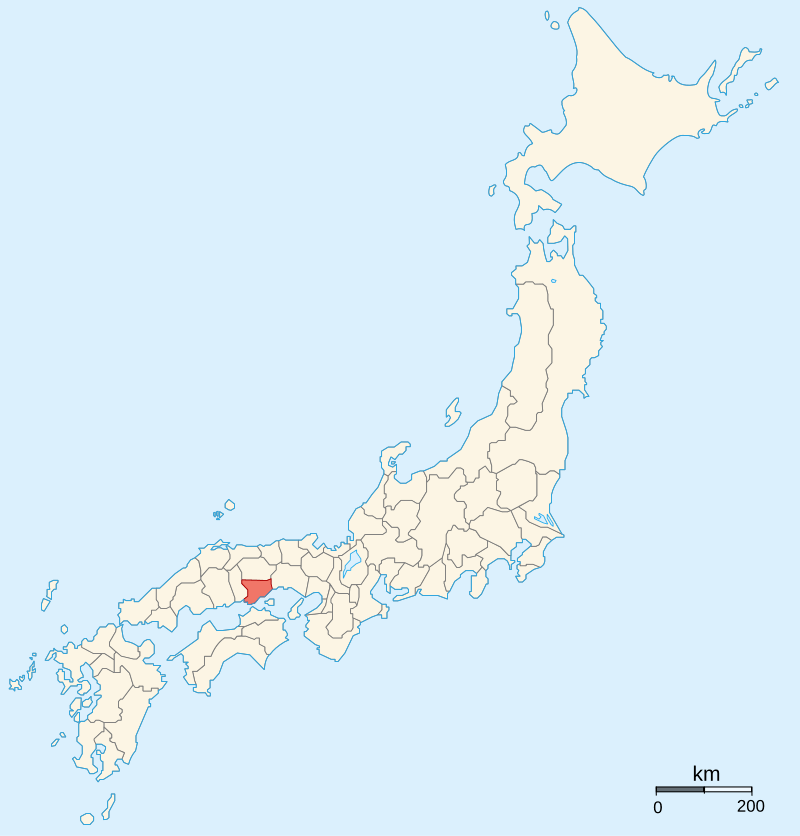

During this period, Hideyoshi made the famous Himeji Castle his base and used it as a springboard for a series of successful campaigns against the Mori over the next few years. By late 1578, he had subjugated (either through conquest or submission) Bizen and Mimasaka Provinces, in addition to his earlier conquests, and he was poised to advance further when the Araki Clan, based at Arioka Castle, rebelled, obliging him to redeploy his forces to put them down.

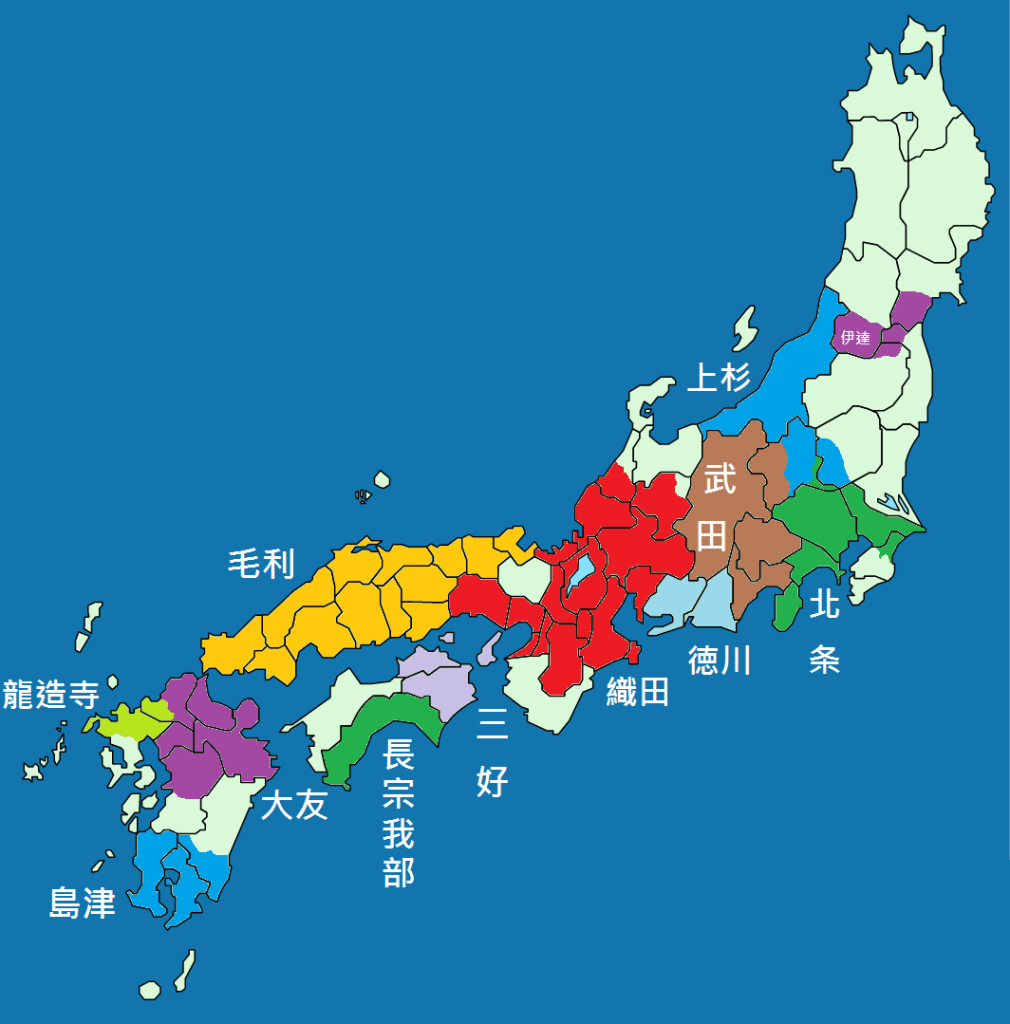

Niko Kitsakis – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40135622による

Able to resume his advance in 1580, Hideyoshi secured Tajima Province, bringing the once-mighty Yamana Clan under his control and incorporating many of their former vassals and members of the clan itself into the new administration, a policy widely praised as the reason that Tajima was swiftly pacified.

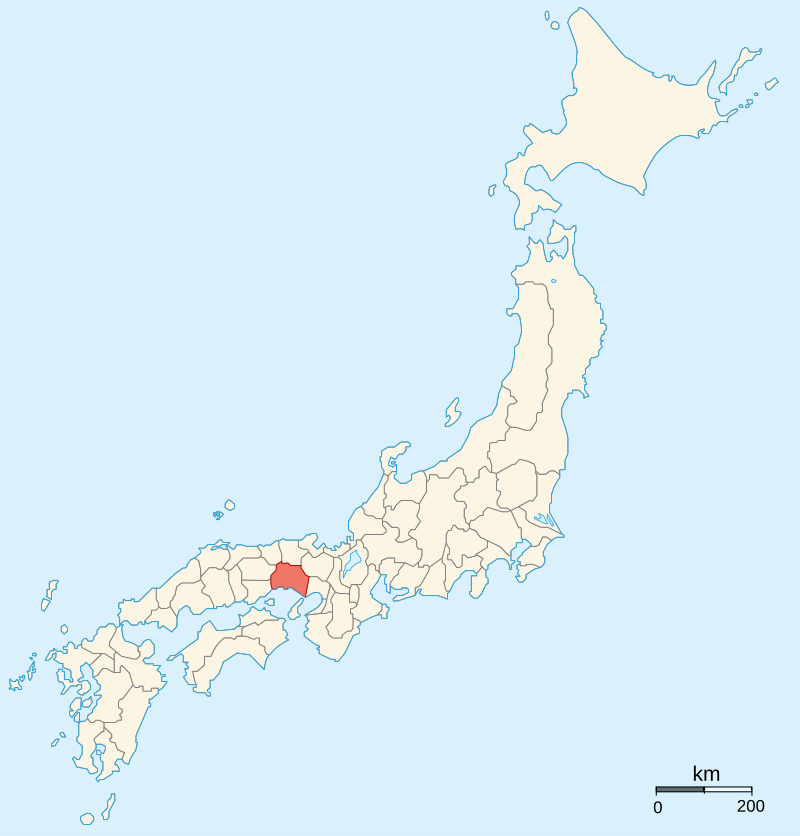

By 1581, he had advanced into Bitchu Province and secured Awaji Island for his master, utilising slow but effective siege tactics, starving his enemies into submission, a time-consuming but strength-preserving strategy. One disadvantage, though, was that it meant you were easy to find should your enemy have sufficient strength elsewhere.

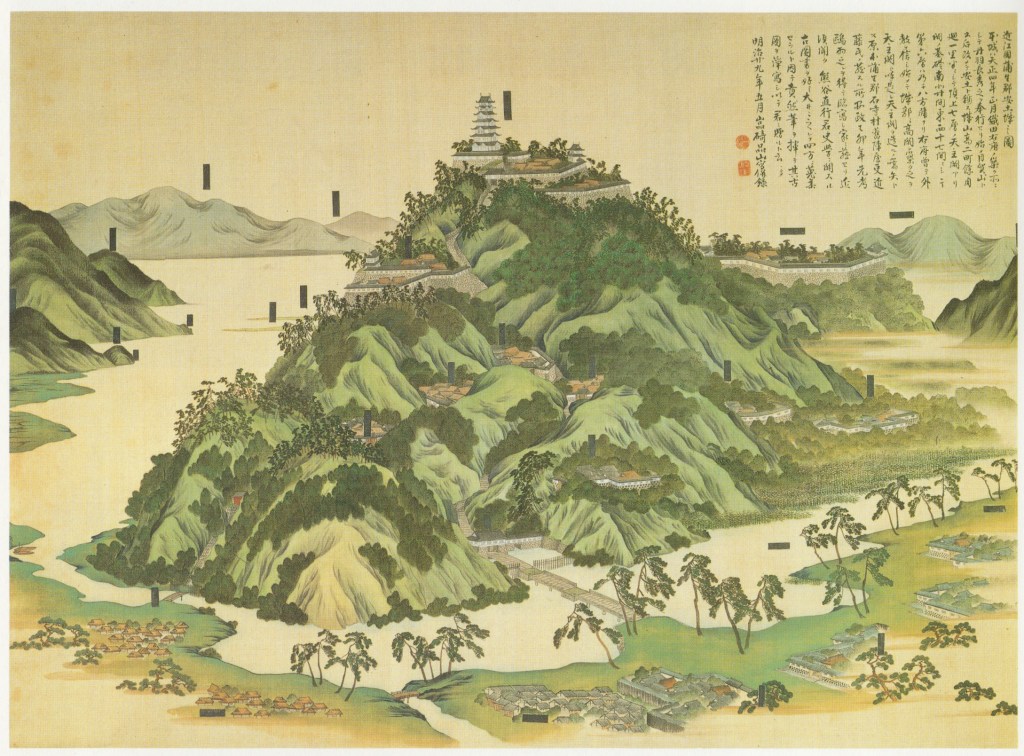

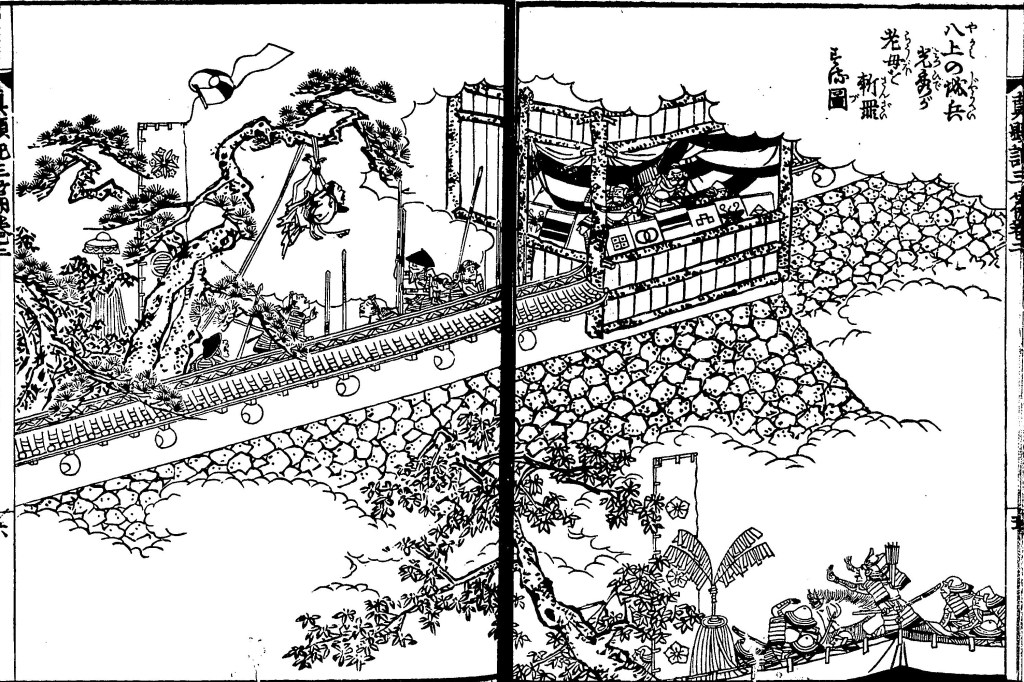

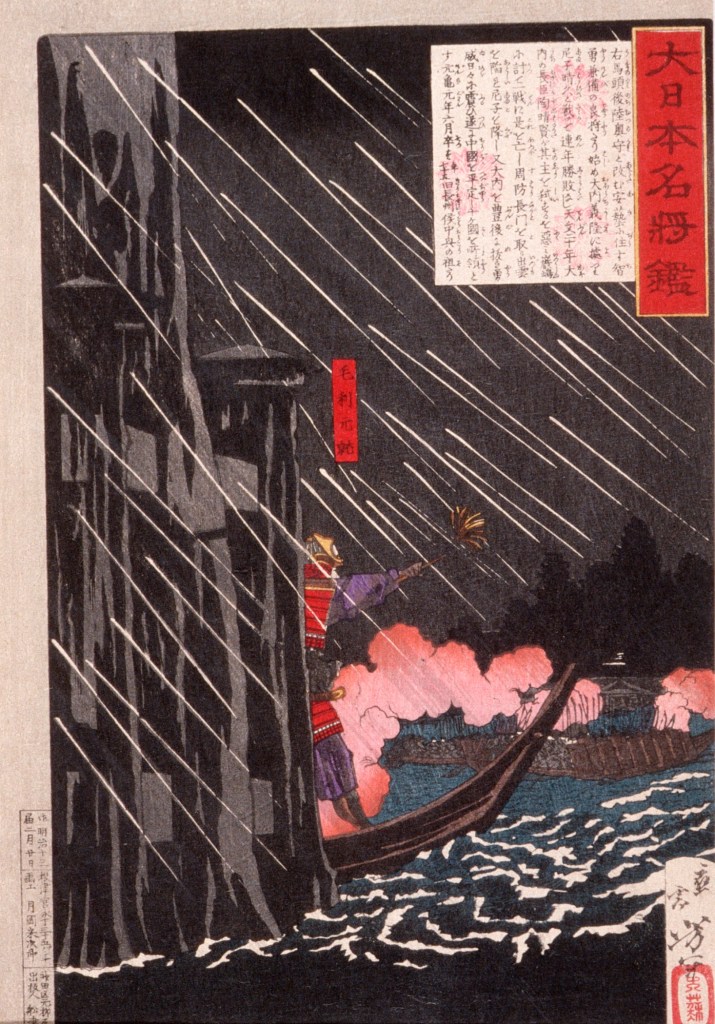

In Spring 1582, Hideyoshi led an army of some 30,000 to besiege the mighty fortress at Takamatsu. Strategically vital for control of Bitchu Province, the castle was defended by 3,000 Mori warriors, who quickly called for aid. Mori Terumoto responded and began mustering an army that would eventually number over 50,000. Hideyoshi now faced a problem: already outnumbered, if he tried to take the formidable fortress by storm, he’d deplete his forces further. On the other hand, trying to starve the garrison, who knew help was on the way, would take too long and risk trapping his army between the walls of the fortress and the vengeful spears of the Mori.

Hideyoshi responded in a typically inventive fashion. Unable to take the castle by storm, he ordered a levee built and the nearby river dammed, diverting water into Takamatsu itself, flooding the castle to such an extent that the garrison’s food supplies were almost completely ruined and they were reduced to communicating by boat.

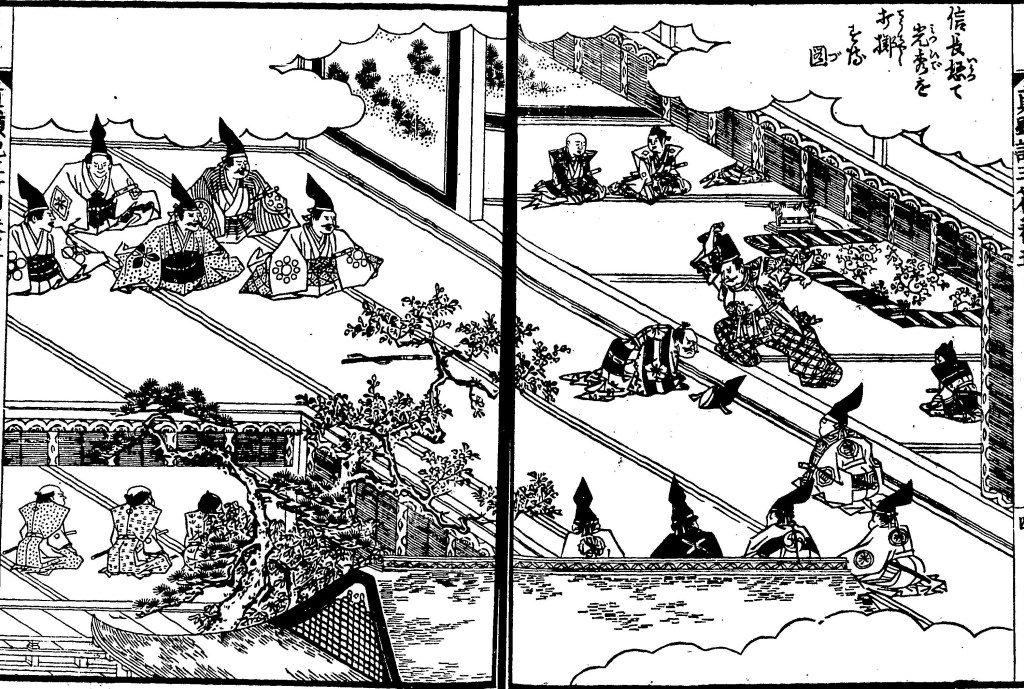

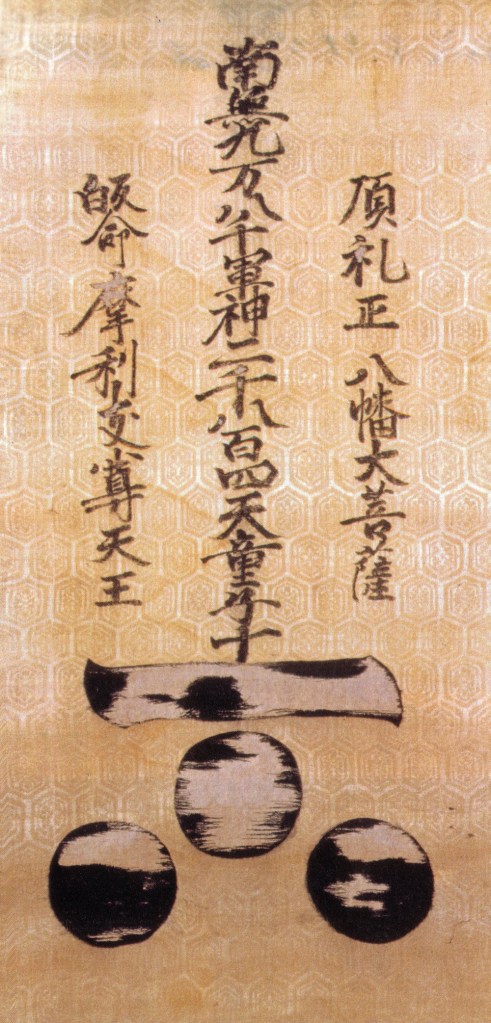

Despite this, the castle still held out, and when news arrived that Terumoto was on the march, Hideyoshi sent a message to Azuchi, requesting immediate reinforcement from Nobunaga. Sensing an opportunity to catch the powerful Mori clan in open battle, where they could be destroyed, Nobunaga quickly dispatched Akechi Mitsuhide to reinforce Hideyoshi, while he went to Kyoto to make arrangements for a larger force that would be sent to finish the job.

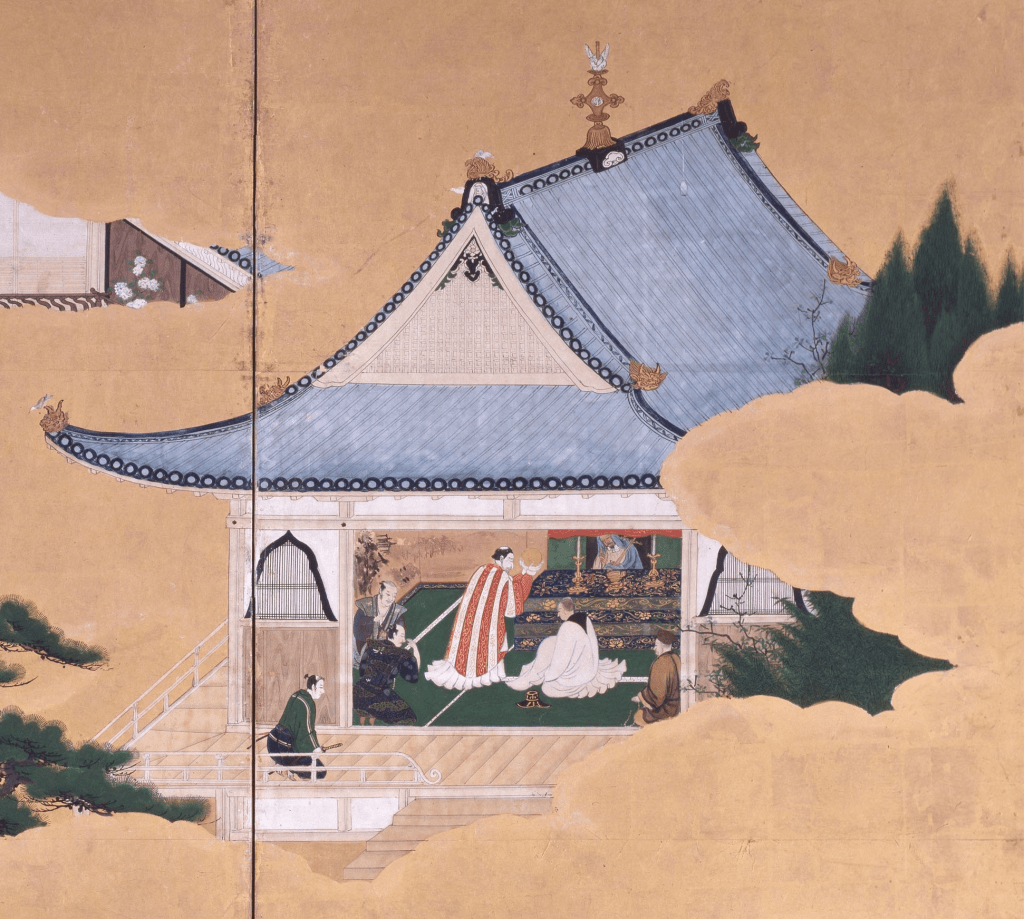

As we already know, Mitsuhide never arrived; instead, he turned his forces around and attacked Nobunaga at his base at Honnoji, killing him and his heir. Hideyoshi was well placed to respond to this betrayal, and he swiftly concluded a peace treaty with the Mori (who were apparently initially unaware of Nobunaga’s death). Some have speculated that his rapid reaction is evidence of his involvement, or at least foreknowledge of the plot, though there’s nothing concrete to suggest that he was anything other than in the right place at the right time.

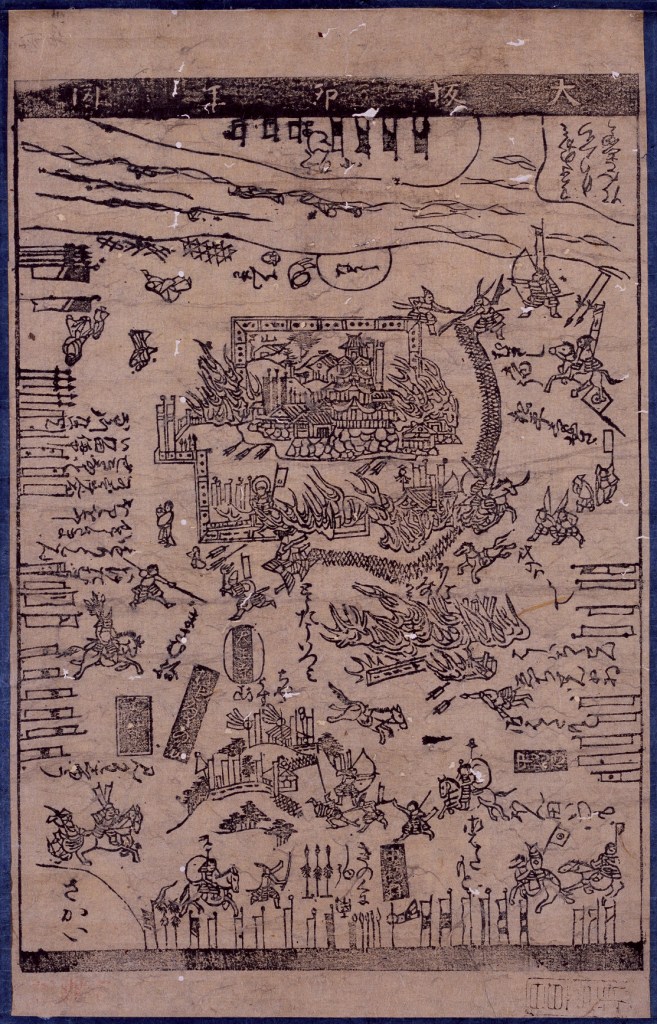

Bakkai – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=92337495による

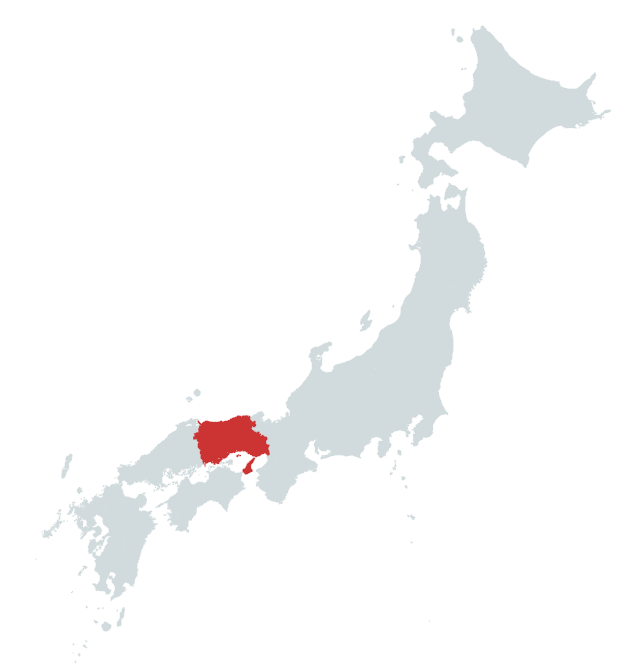

More to the point, Hideyoshi was far from the only player on the board. Hideyoshi’s former rival, Shibata Katsuie, was to the north, with an army facing the Uesugi, while in the Kanto, Takigawa Kazumasu (sometimes called Sakon) had a large army intended to monitor the Hojo. Nobunaga’s son and heir had been killed during the Honno-ji Incident, but his third son, Nobukatsu, had gathered a force at Sakai (modern Osaka) to conquer Shikoku.

Any one of these forces could have been the one to avenge Nobunaga’s death and put an abrupt end to Akechi Mitsuhide’s ambitions. Even Tokugawa Ieyasu was a potential avenger, making his famed escape from mortal danger with the (supposed) help of the famous Ninja of Iga. Ieyasu would return to his home in Mikawa and gather his forces, but events would move quickly, and though all parties moved against Mitsuhide, it was Hideyoshi who struck first.

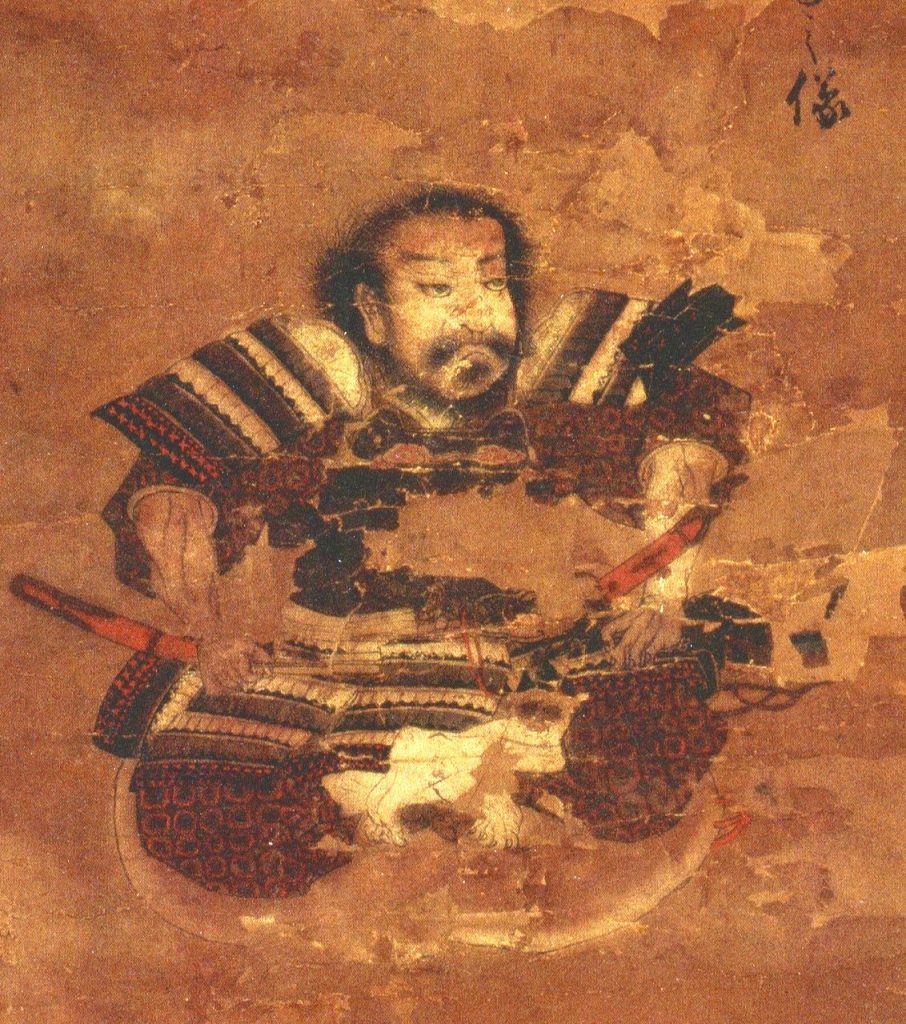

In the days following the Honnoji Incident, Mitsuhide moved to consolidate his position. Unfortunately for him, he faced harsh military and political opposition. On the one hand, Nobunaga’s body had not been recovered from the flames, and rumours abounded that he was still alive. Even among those who may have believed Nobunaga was dead, Mitsuhide commanded little respect. He was a traitor, after all, and surrounded by enemies who wished to avenge Nobunaga and take power for themselves.

Militarily, Mitsuhide was too weak to assert effective control over much territory. He had between 13,000 and 15,000 men, but was obliged to capture and garrison several important castles, whittling his already limited forces down still further. Then there was the speed at which Hideyoshi moved. Mitushide arguably did what he could, and with the limited communications and transportation available at the time, it’s hard to see how he could have moved faster, but Hideyoshi was faster still, and on July 2nd, 1582, just 12 days after Honnoji, the two sides clashed at the Battle of Yamazaki, to the south-east of Kyoto.

The numbers vary by source, but Hideyoshi is said to have had between 20 and 40,000 men, while Mitsuihides had 10 to 16,000. Despite the long odds, Mitsuhide’s army was well-positioned, and the ground around Yamazaki was boggy, limiting movement and reducing Hideyoshi’s advantage in numbers.

Mitsuhide probably understood that a defensive victory against difficult odds would have greatly enhanced his prestige, and for most of the day, Hideyoshi’s army took heavy losses in vicious frontal assaults. Around 4pm, however, reinforcements arrived for Hideyoshi, outflanking Mitsuhide’s position, and causing his army to fall back. As the battle moved to higher and drier ground, Mitsuhide’s force was gradually surrounded and forced back.

Later sources suggest that the casualties were about the same (around 3,000 each), but under attack from three sides, the morale of Mitushide’s army broke first, and by sunset, their retreat became a rout. When the battle was over, it is said that Mitsuhide had just 700 men remaining. His exact fate isn’t clear; some say he was wounded and committed seppuku, while others suggest he was killed by vengeful peasants or bandits. Either way, his head was brought to Hideyoshi the day after the battle, and then displayed at Honnoji, a powerful statement confirming Hideyoshi as Nobunaga’s ‘avenger’ and giving an enormous boost to his credibility.

Hideyoshi would spend a few weeks stamping out the last embers of Mitushide’s rebellion, but despite his military successes, he was not unchallenged as Nobunaga’s successor. The other players, who had all been poised to strike, still remained in the field, and each had their own ambition to rule, either directly or through one of Nobunaga’s other sons.

This would result in the Kiyosu Conference, but we’ll cover that and its consequences next time.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B1%8A%E8%87%A3%E7%A7%80%E5%90%89

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B1%B1%E5%B4%8E%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%9C%AC%E8%83%BD%E5%AF%BA%E3%81%AE%E5%A4%89

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD%E5%A4%A7%E8%BF%94%E3%81%97

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B1%B1%E5%90%8D%E5%A0%AF%E7%86%99

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%89%E6%9C%A8%E5%90%88%E6%88%A6

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%9C%89%E5%B2%A1%E5%9F%8E%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A7%AB%E8%B7%AF%E5%9F%8E

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%82%99%E4%B8%AD%E9%AB%98%E6%9D%BE%E5%9F%8E%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%AB%98%E6%9D%BE%E5%9F%8E_(%E5%82%99%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD)