As we discussed last time, the relationship between the central government in Kyoto and the Kamakura Kubo, the regional military governor, was often quite strained. The decentralised nature of political power in Japan meant that, whilst the Kubo was nominally subordinate to the Shogun, they often acted as semi-independent rulers.

The power of the kubo was, in theory, checked by the Kanto Kanrei, the Shogun’s direct deputy in the Kanto Region, who had, for decades by this point, been a member of the Uesugi Clan.

Like most Samurai families, the Uesugi weren’t a single family, but a loose affiliation of siblings, cousins, and other relatives that shared a name and some common ancestry, but little else, with different branches of the Clan cooperating and opposing each other as the situation demanded.

The strongest branch of the family at this point, and the one holding the position of Kanrei, was the Yamanouchi Uesugi, so named because of their residence in an area of Kamakura called, you guessed it, Yamanouchi. This particular branch of the family actually took over the position from the branch which had risen in rebellion in 1416 and been defeated.

The Kanrei in the 1430s was Uesugi Norizane. He found himself in a fairly unenviable position. Although the kanrei was officially the subordinate of the Kamakura Kubo, the Shogun in Kyoto had the final say over who would actually hold the position, meaning that, in practice, the kanrei often found himself beholden to the will of the Shogun over that of his direct superior.

This was probably fine at a time when Kamakura and Kyoto were in agreement, but by now, this was definitely not the case. As we talked about briefly last time, the Kamakura Kubo, Ashikaga Mochiuji, often followed an independent path, and this defiance led to a serious breakdown in his relationship with the Shogun.

In 1429, the accession of a new Emperor called for a change in the Era name. This was (and arguably still is) a big deal in Japanese culture; whenever a new Emperor ascends the throne, the Era name is changed. It can also be changed after significant or otherwise tragic events, as those in power seek to figuratively draw a line under the past.

A change of era is often an administrative formality for most, but this time, Mochiuji, being the independent-minded fellow that he was, apparently refused to adopt the new era name. This might seem like a petty decision to us, but it was, in effect, Mochiuji announcing to the world that he didn’t recognise the new era, and by extension, the new Emperor.

Things got worse following the death of Shogun Yoshimochi in 1431. Mochiuji had expected to be called upon to be the next Shogun, as Yoshimochi had died without heirs. When Ashikaga Yoshinori, a monk, was selected instead, Mochiuji was angry enough to consider marching on Kyoto.

This is where Uesugi Norizane rejoins our story. He dissuaded his hot-headed master, and no force was sent. In addition, he arranged for formal apologies regarding the Era change and even went so far as to return lands that had been confiscated by Mochiuji to the Shogun.

Norizane is also recorded as having sent expensive gifts to Kyoto in an attempt to smooth over the considerable animosity that had built up towards Mochiuji there. Norizane was evidently trying to steer a moderate course; he owed his position to the Shogun, but he was nominally subordinate to the Kubo. When these two masters were in opposition, Norizane found himself caught in the middle.

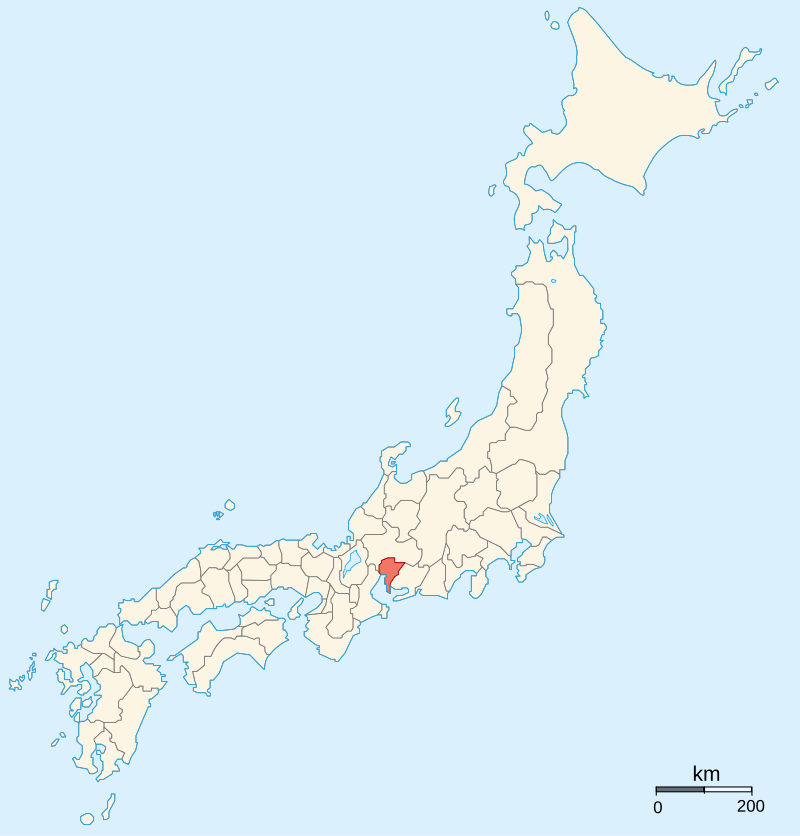

In 1436, his position got even worse. That year, fighting broke out in Shinano Province between rival factions seeking control of the province. One side called on Mochiuji for help, and he was eager to go, but Norizane intervened, pointing out that Shinano was not one of the provinces that were under the authority of the Kamakura Kubo. Thus, no forces were sent.

The warlord who had requested Mochiuji’s help was defeated, and in 1437, Mochiuji planned to raise an army and march into Shinano anyway, presumably to avenge his fallen comrade. This time, however, rumours spread that the army was actually to be sent against Norizane.

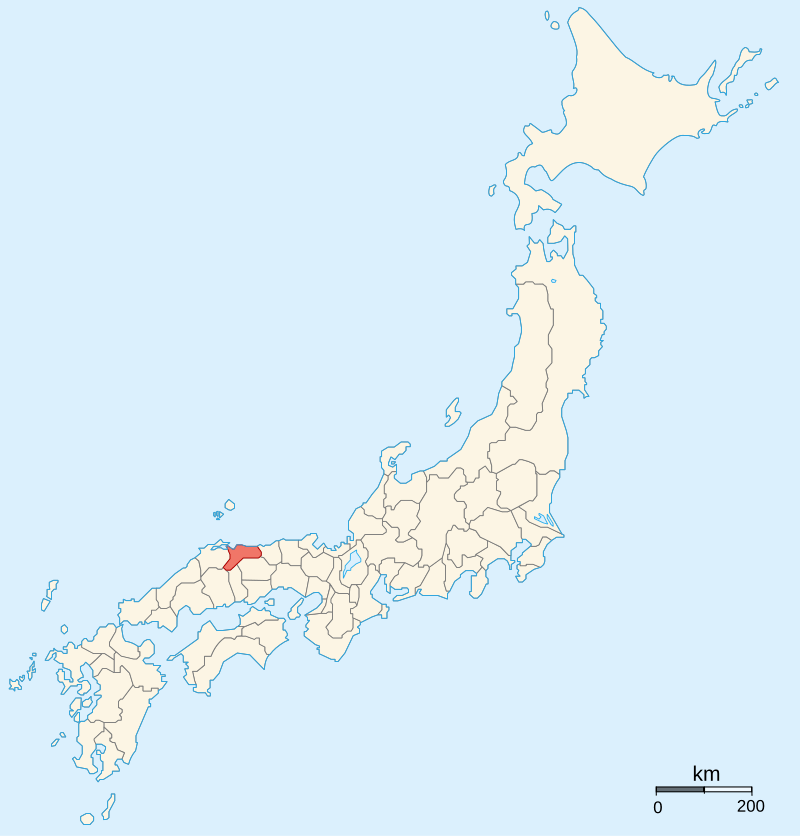

Things quickly got out of control after that. Although there was some attempt to negotiate, Norizane fled the Kanto entirely, retreating to the Uesugi stronghold in Echigo Province. There was a brief reconciliation in 1438, but things broke down again quickly afterwards, with Norizane resigning as kanrei.

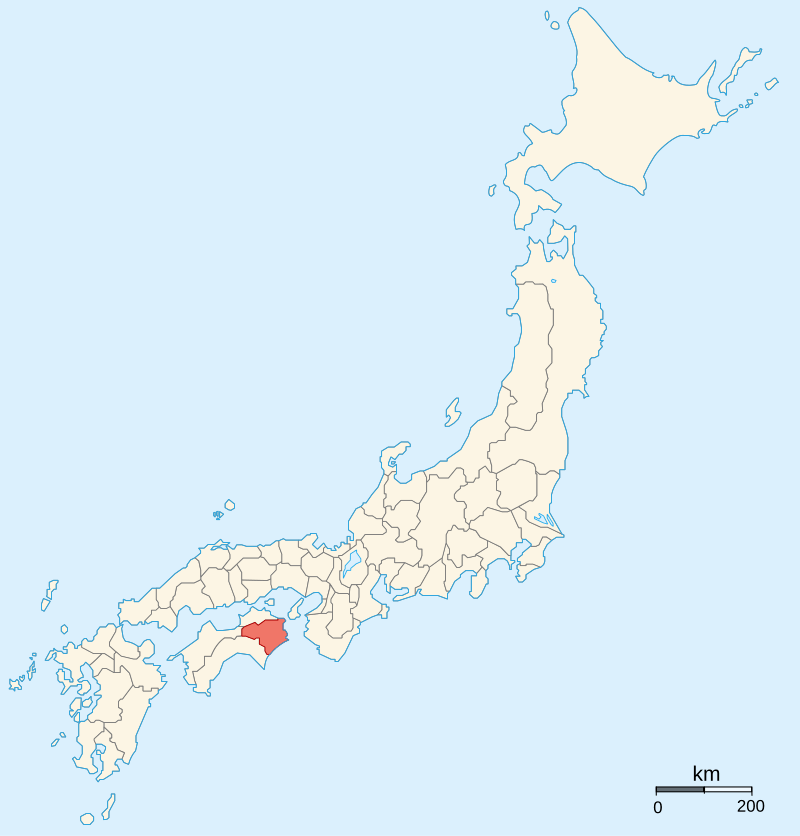

This time, Norizane fled to Kozuke Province, and Mochiuji sent an army after him. In response, Norizane called for help from the Shogun, and Yoshinori, who had been waiting for an excuse to deal with the troublesome kubo, readily agreed.

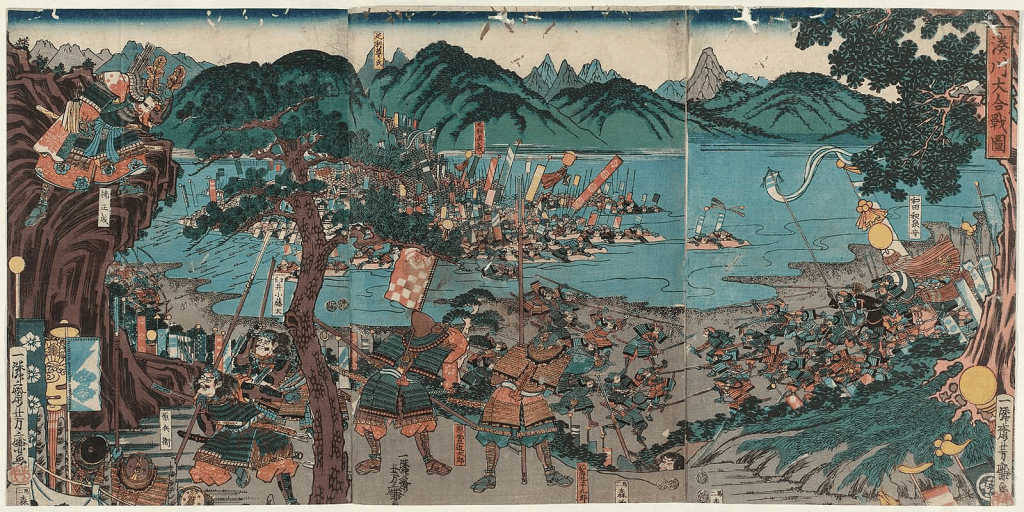

A coalition of Kanto warlords loyal to the Shogun was assembled, and the Shogun used his influence at court to have an Imperial Banner issued to the army, effectively turning it into an Imperial army, and all those who opposed it into rebels against not only the Shogun but the Emperor himself.

What impact this had on the morale of Mochiuji and his men isn’t clear, but throughout September and October 1438, their forces were repeatedly defeated, until eventually Mochiuji surrendered and attempted to become.

Uesugi Norizane, continuing his policy of moderation, pleaded for Mochiuji’s life, and for his son to be allowed to take the position of Kubo. Shogun Yoshinori, however, was in no mood. Mochiuji had been a thorn in his side for decades, and he would not pass up the opportunity to deal with him.

Mochiuji and his son were forced to commit suicide, and the position of Kamakura Kubo was temporarily abolished. That wouldn’t last long, though, and in 1440, Yoshinori attempted to have his own son appointed as the new kubo.

This didn’t sit well with former loyalists of Mochiuji, and a rebellion, led by the Yuki Clan, broke out in the same year, with the stated aim of restoring one of Mochiuji’s sons to their late father’s position.

In April 1441, the rebellion was defeated, and Mochuji’s surviving children were brought to Kyoto. Yoshinori continued his plans to appoint his son as kubo, but then fate took a turn, as it so often does.

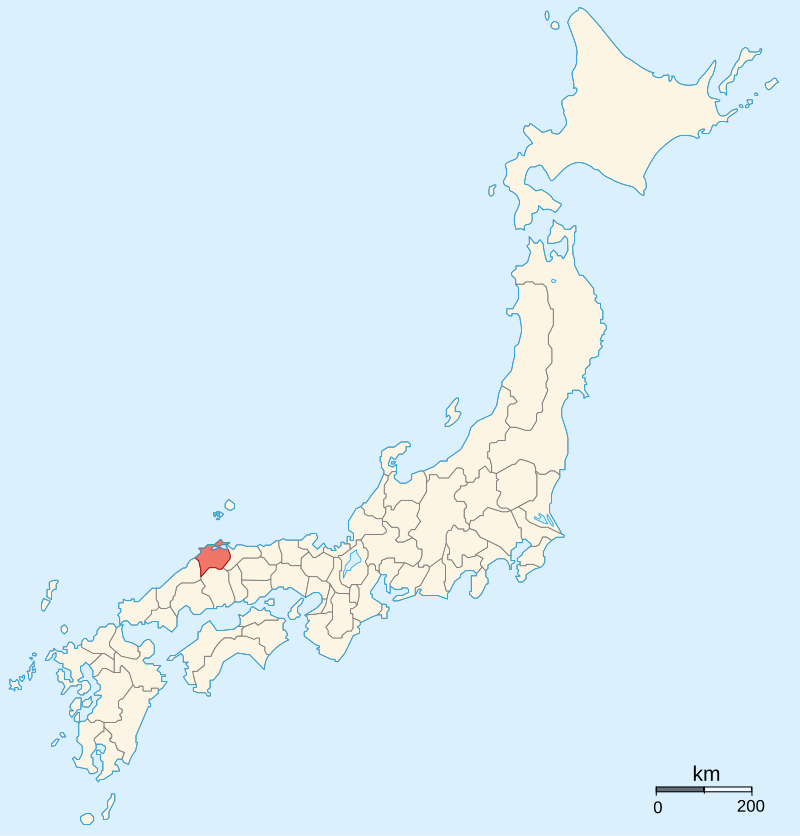

In June 1441, Yoshinori was invited to a banquet at the residence of the Akamatsu Clan, officially to celebrate the Shogun’s recent victory. When he arrived, the gates were locked, and he was set upon by a band of armed men and cut down.

The immediate motive of his killer appears to have been either revenge for the confiscation of family property earlier in his reign or the fear of being politically purged. Historians speculate that Yoshinori was becoming increasingly paranoid, with the Imperial Nobility and Samurai class becoming fearful of the possibility of being denounced and facing exile or execution.

A phrase used by contemporaries to describe this period of Yoshinori’s reign is ‘万人恐怖’ Bannin Kyofu, or Universal Fear, which gives you a good idea of the mood.

In the immediate aftermath of the killing, rumours of a wider conspiracy abounded, but it soon became clear that the Akamatsu Clan had acted alone; the government’s attention focused on who would be the next Shogun. The most appropriate choice was Yoshinori’s son, Yoshikatsu, but he was just a boy, and it wasn’t until November 1442, 18 months after his father’s death, that Yoshikatsu was elevated to Shogun, despite being just nine.

With Yoshinori’s death and his replacement by a boy, the strong, often dictatorial power of the Shogun was significantly reduced. Yoshikatsu would rely on a council of powerful lords to handle the realm until he came of age, but that didn’t happen, as Yoshikatsu fell in and died in July 1443, only eight months into his reign. His sudden death led to the spread of several rumours, from a fall from a horse to assassination, but historians generally believe he died of illness, possibly dysentery.

CC 表示 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9662197

Yoshikatsu was replaced by his brother, Yoshimasa, who was even younger, and he wouldn’t be officially declared Shogun until 1449, by which time real power had shifted from the Shogunate to several powerful clans.

Though no one knew it then, the Ashikaga Shogunate had begun what would prove to be a terminal decline.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%8E%8C%E5%80%89%E5%85%AC%E6%96%B9

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E6%95%99#

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%98%89%E5%90%89%E3%81%AE%E4%B9%B1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E5%8B%9D

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E6%94%BF

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashikaga_Yoshimasa