(I had to make this a two-parter or the joke in the title wouldn’t have worked.)

Note: Takeda Shingen’s real name was Harunobu, with Shingen being a name he took as part of his religious vocation. In keeping with my policy of using the names that figures are best known by, we’ll be referring to him as Shingen throughout this post, but in other sources, he is often called Harunobu, just so you know.

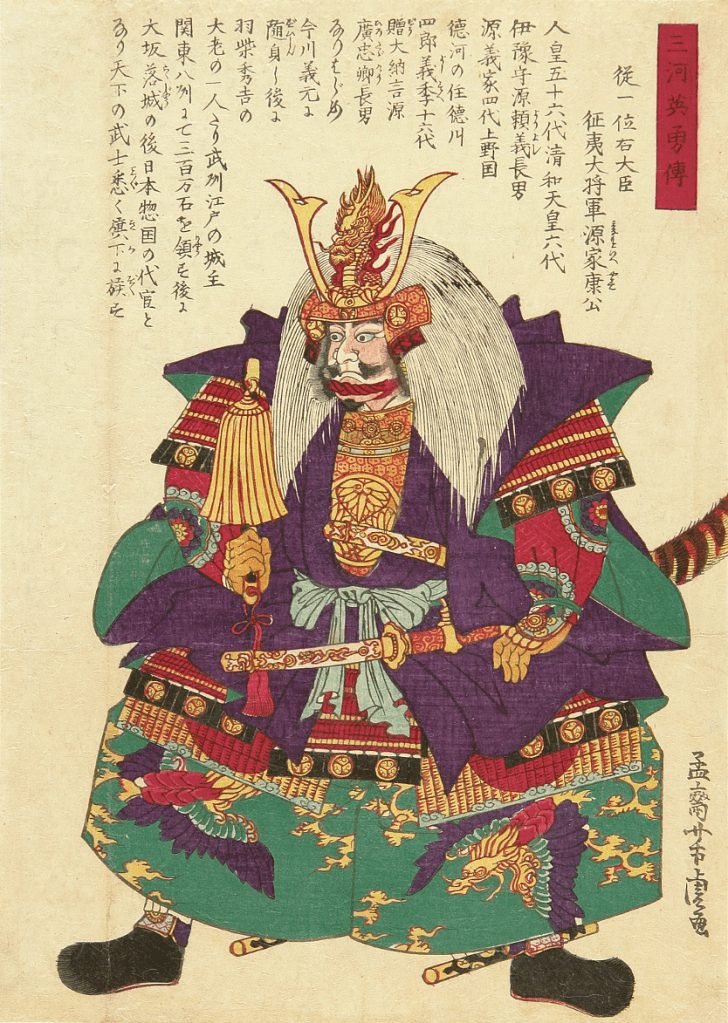

In June 1541, Takeda Shingen (then known as Harunobu) overthrew his father, Nobutora, and established himself as the leader of the Takeda Clan and master of Kai Province. As we mentioned last time, the exact reasons for this coup aren’t known; some sources say he was overthrowing his tyrannical father, others that it was a self-serving power grab, but whatever his motivation, Harunobu was in charge, and he had big plans.

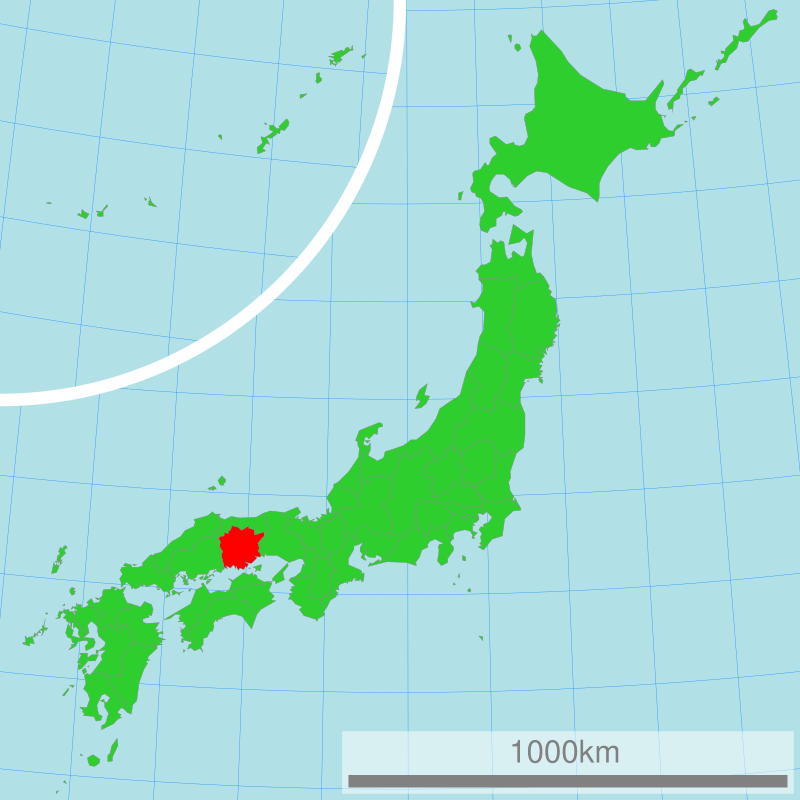

The strategic and diplomatic situation that Shingen inherited was full of risks and opportunities. His father had successfully subjugated all of Kai Province and even expanded the borders of Takeda control into neighbouring Shinano. He had been a fierce rival of the Hojo Clan, based in Izu and Sagami Provinces (modern day Kanagawa Prefecture), but had established peaceful relations or alliances with other powerful neighbours.

Almost immediately, Shingen would chart a radically different course. His father had been allied with the Suwa Clan of Shinano, to the Takeda’s north, but in June 1542, Shingen invaded Shinano Province, defeating the Suwa at the Battle of Kuwabara Castle, and forcing their leader to commit suicide, absorbing their lands into his own.

Though the result of this campaign is relatively undisputed, the exact nature of how things got started is more controversial. Allegedly, in March 1542, before Shingen’s invasion of Shinano, the Suwa Clan and their allies attacked first, before being defeated at the Battle of Sezawa. The problems come from there being little evidence that this battle ever took place, with some historians suggesting that it might have been a later invention to justify Shingen’s invasion after the fact.

Regardless of its origins, the campaign would be a long and ultimately successful one for Shingen. A series of battles through the late 1540s put the Takeda in a pre-eminent position in Shinano. By 1553, the clan occupied almost the entire province; only the far north, around the modern city of Nagano, remained outside their control.

This would prove significant later, but during this period, Shingen would also prove himself to be a savvy political player as well. In 1544, Shingen made peace with the Hojo and then mediated between them and the Imagawa, bringing an end to their conflict, allowing both clans to focus on issues elsewhere, and securing peace on Kai’s southern borders.

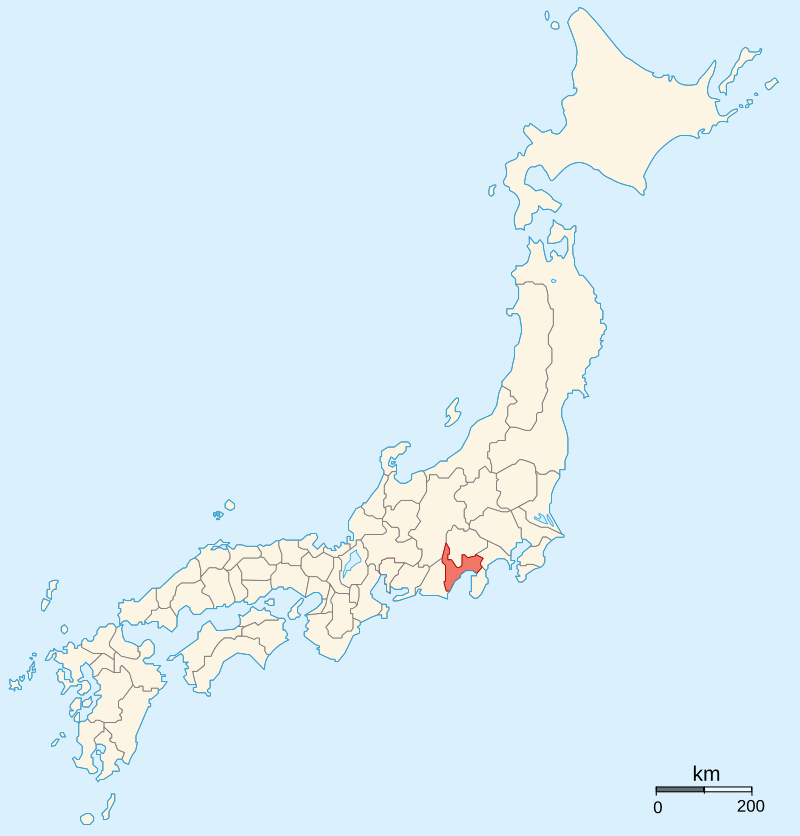

Turning his attention back to Shinano, Shingen would launch semi-annual campaigns into Shinano, winning a series of victories against the clans based in the province, and slowly extending Takeda dominance. He didn’t have it all his own way, however; in March 1548, the Takeda marched against the Murakami Clan, one of their chief rivals for control of Shinano. The Battle of Uedahara was arguably a draw, as both sides suffered similar losses; however, the Takeda advance was stopped, and they lost several key commanders, with Shingen himself being wounded.

In July of that year, another of Shingen’s enemies in Shinano, the Ogasawara Clan, sought to take advantage and push the Takeda back into Kai; however, at the Battle of Shiojiri Pass, the Ogasawara were decisively defeated by a resurgent Shingen, and the momentum would swing back in favour of the Takeda.

In 1550, Shingen took control of what is today called the Matsumoto Basin (around the modern city of the same name), but a second serious defeat would follow in September of that year, as the Takeda tried and failed to take Toishi Castle. Sources differ, with some saying the Takeda lost a fifth of their forces, and others saying it was as many as two-thirds.

Although losses were clearly heavy, as with Uedahara a few years earlier, Shingen wasn’t on the back foot for long. In April 1551, Toishi Castle was taken (supposedly through trickery), and over the next two years, he would drive the Murakami Clan out of Shinano, until they were forced to flee Shinano entirely.

This left Shingen in control of almost all of Shinano, but it also presented a new problem. In fleeing Shinano, the Murakami Clan sought the support of another powerful player in the region, the lord of Echigo Province and lord of a clan that was every bit as powerful as the Takeda, Uesugi Kenshin. Though neither side knew it yet, the stage was now set for one of the great rivalries of the Sengoku Period.

Shingen and Kenshin would clash repeatedly in the years to come, mostly at and around the now-famous battlefield of Kawanakajima (which literally means “The Island in the River”). The first clash of these rivals would come in April 1553, and would be indecisive, but the frontier in northern Shinano would remain volatile.

In 1554, Shingen strengthened his diplomatic position by marrying his son to a daughter of the Imagawa Clan, followed shortly afterwards by a marriage of his son to a daughter of the Hojo Clan, who were also conveniently an enemy of the Uesugi. Following the establishment of the so-called Koso Alliance, Shingen secured control of southern Shinano and advanced into neighbouring Mino Province, securing the submission of several border clans in the process.

The second and third Battles of Kawanakajima would be fought in 1555 and 1557, respectively, and both would end in further stalemate, but following the third battle, the Shogun (very much a figurehead at this point) issued a command that both sides make peace. Kenshin accepted immediately, but Shingen responded that he would only make peace if the Shogun named him shugo (governor) of Shinano, which was duly granted.

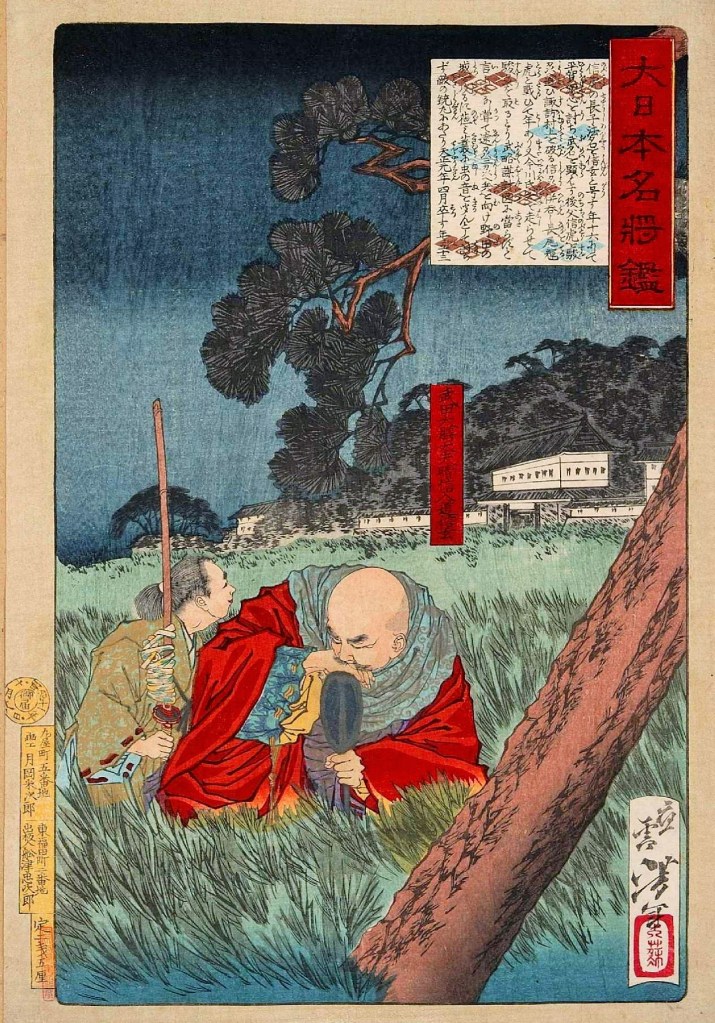

In 1559, the Eiroku Famine and a serious flood in Kai Province led to the cessation of hostilities (at least temporarily) and that year, Shingen became a monk, formally adopting the name Shingen. Exactly why he chose to become a monk isn’t recorded, but it is speculated that it was in response to the twin disasters of famine and flood, with Shingen perhaps seeking divine intervention.

Whether or not the gods were listening isn’t known, but after 1560, Shingen and the Takeda clan would begin to move away from older alliances and local authority and towards a policy of seeking power on the national stage. In May 1560, the Imagawa, allies of the Takeda, were severely defeated by the rising star that was Oda Nobunaga, and although Shingen publicly declared his intention to continue the alliance, he made secret arrangements with Nobunaga, with his son, Katsuyori, marrying Nobunaga’s adopted daughter.

The relationship continued to break down until 1567, when the Imagawa ended the trade of salt (abundant in their coastal provinces) to Kai, effectively cutting the Takeda off from this vital resource. The next year, in cooperation with a former Imagawa vassal, Tokugawa Ieyasu (then known as Matsudaira Motoyasu), Shingen invaded Imagawa territory, taking Suruga Province, whilst Ieyasu invaded Totomi, to the west.

The invasion was a military success, but had serious diplomatic repercussions more or less immediately. The relationship with the Imagawa was obviously already pretty bad, but when Shingen tried to enlist the help of the Hojo in attacking Suruga, he was rebuffed, and the Hojo would instead send troops to support their Imagawa allies.

The relationship with Ieyasu, always a marriage of convenience, broke down swiftly as well. The erstwhile allies got into a dispute about actual control of Totomi Province, and Ieyasu took his proverbial ball and went home, making peace with the Imagawa, and ignoring his previous agreement with Shingen.

Shingen, now surrounded by potential enemies, sought out allies amongst the pre-existing enemies of the Hojo, and launched a counter-attack in 1569, getting as far as the Hojo capital at Odawara, which he briefly laid siege to before withdrawing, contenting himself with burning the town around the fortress.

Retreating to Kai, Shingen defeated a pursuing Hojo force at the Battle of Mimasu Pass, effectively ending the Hojo threat to Kai and preventing them from intervening further in the invasion of Suruga. By the end of 1569, Shingen was in complete control of the province.

Shingen would consolidate his position, but in 1571, Oda Nobunaga, with whom Shingen had enjoyed good relations previously, attacked and burned Mt Hiei, one of the holiest sites in Japanese Buddhism, sparking religious outrage across the realm.

Shingen, who was a monk, remember, was personally outraged, and allowed surviving monks from Mt Hiei to take refuge in Kai. In 1572, the Shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiaki, sent a letter, reaching out to Shingen and calling on him to march on Kyoto and destroy Nobunaga.

By this point, the Shogun’s options were severely limited (Yoshiaki would prove to be the last Ashikaga Shogun), but it was probably a smart move. By the early 1570s, Nobunaga had risen to become one of the most powerful warlords in Japan, and there simply weren’t that many contemporaries who could match him for strength and strategic acumen.

Shingen had the strength, he had the experience, and after Mt Hiei, he had plenty of reason to answer the Shogun’s request. Gathering somewhere in the region of 27,000 men, a gigantic army for the time, the Takeda Steamroller began its move west in October 1572, first striking at Tokugawa Ieyasu’s territory in Mikawa Province, taking several fortresses in a matter of days, and forcing Ieyasu to call for help from Nobunaga.

Nobunaga, however, was busy elsewhere, and could only spare 3000 troops to help, not nearly enough, and whenever Tokugawa forces made a stand, they were defeated. Initially, Ieyasu sought to defend the castle at Hamamatsu, a strong position, but weak strategically, as Shingen was able to bypass it on his march to Kyoto.

Forced to either give battle or see himself rendered effectively impotent, Ieyasu marched out and met Shingen at Mikatagahara in January 1573. The result was a catastrophic defeat for Ieyasu, who saw his army scattered in all directions, with thousands left for dead on the battlefield. It was only due to the heroic resistance of several of his retainers that Ieyasu himself was able to survive the battle.

Flush with victory, the Takeda forces would continue their advance, defeating what remained of the Tokugawa Clan and securing many castles throughout Mikawa Province. At that point, it may well have seemed that Shingen was well placed to launch a final thrust at the capital, and it isn’t unreasonable to speculate that, had such an attack occurred, he may have been successful, and we might today be talking about a ‘Takeda Shogunate’.

Alas, it wasn’t to be. Despite his military and political acumen, Shingen was still just a man. His health had been getting steadily worse for years. As early as 1571, he was forced to abandon military action due to symptoms as severe as coughing up blood, and after Mikatagahara, his condition took a turn for the worse.

In early spring 1573, Shingen made the decision (or had it made for him) to return to Kai Province to recover his health. Somewhere along the road home, however, he died. Exactly when and where he passed isn’t clear, but most historians agree it was sometime in April. According to Shingen’s will, his death was kept a secret, and although this would later lead to speculation around the circumstances of his death (perhaps best seen in the film Kagemusha), Shingen’s remains were most likely returned to his capital in modern Kofu, Yamanashi Prefecture.

Shingen’s sudden death raises some of the most interesting ‘what if?’ questions of this period. He was arguably one of the few men who could match Oda Nobunaga for strength and cunning, and it is possible that, if he had lived, he might have defeated Nobunaga and perhaps led the unification of Japan himself.

This is ultimately not how things played out, but Shingen’s role in Japanese history didn’t end with his death. Although he had a well-earned reputation as a warrior, he was also a wise administrator and reformer, and many of the policies he introduced in his territories were adopted by those who came after him, with some even going on to influence Japanese law after the Sengoku Jidai, but we’ll talk about that another time.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AD%A6%E7%94%B0%E4%BF%A1%E7%8E%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%89%E6%96%B9%E3%83%B6%E5%8E%9F%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%9D%BE%E6%9C%AC%E7%9B%86%E5%9C%B0

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%A0%A5%E7%9F%B3%E5%B4%A9%E3%82%8C

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A1%A9%E5%B0%BB%E5%B3%A0%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%8A%E7%94%B0%E5%8E%9F%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%94%B2%E7%9B%B8%E9%A7%BF%E4%B8%89%E5%9B%BD%E5%90%8C%E7%9B%9F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%AE%AE%E5%B7%9D%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%B2%B3%E6%9D%B1%E3%81%AE%E4%B9%B1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%AB%98%E9%81%A0%E5%90%88%E6%88%A6

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%94%B2%E5%B7%9E%E6%B3%95%E5%BA%A6%E6%AC%A1%E7%AC%AC

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%A1%91%E5%8E%9F%E5%9F%8E%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%80%AC%E6%B2%A2%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashikaga_Yoshiaki

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Mikatagahara