The Nanbokucho Period is named the Northern and Southern Courts Period in English because that is what it was. The division of the rival Imperial Courts was reflected across Japan during this period. There were few, if any, periods of extended peace, and rival factions would swear allegiance to one court or another, and then use that as an excuse to attack their local rivals.

In many cases, of course, these rival warlords didn’t even bother with the formality of declaring allegiances; they settled their disputes through force because they could. They had the men, and there was no central government strong enough to stop them.

That began to change with the third Ashikaga Shogun, Yoshimitsu. As we talked about last time, he was no idle ruler, nor was he simply the first amongst equals when it came to the brutish thuggery of this early Samurai period. Yoshimitsu played rival clans off each other to increase the military power and prestige of the Shogunate, but he also ingratiated himself with Imperial loyalists by taking a position in the government of the Northern Court, so much so that it began to appear that the Emperor’s orders, and those of the Shogun were one and the same.

Yoshimitsu wasn’t just a political animal, though; he understood the nature of the conflicts around Japan came from the largely independent nature of the Shugo (regional lords), in which even fairly loyal Clans were left to handle their own affairs. Yoshimitsu’s solution to this was an enforced residence policy.

Basically, the Shugo lords were required to live in Kyoto (with the exception of those based in the Kanto and on Kyushu). Once there, they were forbidden from leaving the capital without the (rarely granted) permission of the Shogun. Leaving Kyoto without this permission was seen as an act of rebellion, and, having seen what had befallen the Yamana and Toki Clans, most Shugo fell in line.

In the short term, this went a long way to curbing their often violent independence, but long-term, it proved to be a disastrous policy. Whilst the first generation of lords to take residence in Kyoto left trusted relatives in charge, within a few decades, their descendants had become the real power in the provinces. Much like the Imperial Court in the 8th and 9th centuries, the Shugo grew to become out of touch with the nominally subordinate provincial officials, once again leading to a catastrophic decentralisation of power, and laying the foundations for what would eventually become the Sengoku Jidai, the Age of the Country at War.

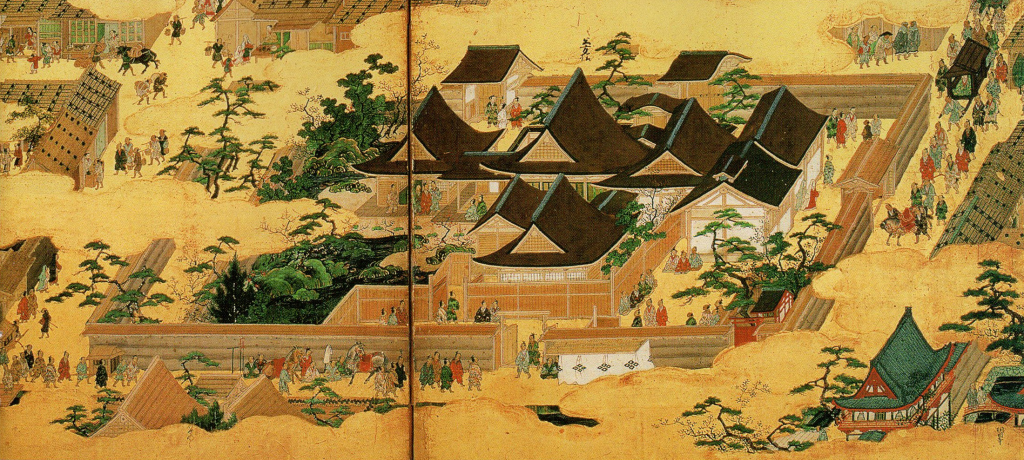

With this policy also came a shift in the economic and cultural centre of gravity in Japan. With the majority of the wealthiest Shugo now required to live permanently in Kyoto, the wealth that had previously been dispersed in the provinces now became centred on the capital.

During previous eras, wealth had primarily been derived from land, but under Yoshimitsu, a new urban middle class formed from the moneylenders, traders, and other commercial agents that benefited directly from the sudden influx of wealthy, image-conscious nobles in their midst.

Throughout the late 14th century, Kyoto flourished as a centre of wealth and culture, with some modern icons of Japanese culture, such as Renga Poetry and Noh Theatre, emerging during this time.

By Yoshiyuki Ito – Imported from 500px (archived version) by the Archive Team. (detail page), CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=71346350

It was, however, also a period where ‘traditional’ social norms were challenged. The Samurai, who had emerged primarily as a rural class, were a rough and ready sort, fond of extravagant living, flashy clothes, and frequent outbursts of violence.

This lifestyle, often called Basara in contemporary sources, was at odds with the more formal, rigid, and genteel lifestyle of the ‘old’ families in and around Kyoto, who associated art and culture with the more traditional styles of the Imperial Court.

Whilst the Shogun was relatively strong and capable (as Yoshimitsu was), these tensions could be managed, but the seeds of further trouble were already being sown, even as the Shogun appeared to be bringing an end to the chaos.

The Meitoku Treaty

Throughout the late 1380s and into the 1390s, Shogun Yoshimitsu either provoked or took advantage of chaos in several powerful clans, asserting his power and weakening any serious support for the Southern Court. In 1392, after having decisively broken the power of the Yamana Clan, he turned his attention to the Southern Court and its remaining allies.

Northern Forces attacked Chihaya Castle in early 1392, and after it fell, the Southern Court was effectively defenceless. At this point, however, Yoshimitsu took on the role of peacemaker; instead of attacking the Southern Court, he opened negotiations.

The Southern Court, for their part, seem to have seen the writing on the wall, and faced with a peaceful outcome or the prospect of annihilation, they chose peace. In November 1392, Emperor Go-Kameyama (Southern Court) travelled to Kyoto and handed over the three Imperial Treasures to Emperor Go-Komatsu (Northern Court).

In exchange, it was agreed that, going forward, the line of the Northern Emperors and the Southern Emperors would alternate on the throne, with Go-Komatsu (Northern) being succeeded by a Southern Emperor, and so on.

As a side note, the Northern Court were apparently strongly opposed to the treaty, as they considered themselves the only legitimate line and didn’t wish to alternate with the ‘illegitimate’ Southern Line. It is perhaps a testament to just how powerful the Shogunate had become then, when the treaty was agreed to, with both sides evidently being mutually dissatisfied, but compelled to agree due to the overwhelming strength of the Shogun.

So, peace came to Japan at last. A strong Shogun, a cowed Imperial Court, and a capital that had become a wealthy, bustling centre of commerce, art, and culture. All was right in the world, except, of course, it wasn’t.

Yoshimitsu was an impressive leader, and through his personal drive, energy, and acumen, he ensured that everything went the Shogunate’s way. Bringing an end to the Nanbokucho Period was no mean feat, and we shouldn’t understate it, but unfortunately for Japan, Yoshimitsu, like most people, was mortal.

Though Yoshimitsu would formally retire as Shogun and become a monk in 1394, he continued to hold onto real power until his death in 1408, after which things began to unravel pretty quickly.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%98%8E%E5%BE%B3%E3%81%AE%E5%92%8C%E7%B4%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%A1%E7%B5%B1%E8%BF%AD%E7%AB%8B#%E5%BE%8C%E6%97%A5%E8%AB%87

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8D%83%E6%97%A9%E5%9F%8E

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8D%97%E5%8C%97%E6%9C%9D%E6%99%82%E4%BB%A3_(%E6%97%A5%E6%9C%AC)

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%81%B0%E3%81%95%E3%82%89

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%80%A3%E6%AD%8C

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%83%BD%E6%A5%BD

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/N%C5%8Dgaku

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noh

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashikaga_Yoshimitsu