As we’ve already seen, by the mid-13th century, the Kamakura Shogunate was ruled in all but name by the powerful Hojo Clan, who ruled as shikken or regents for the Shoguns, who were nothing more than puppets.

In Kyoto, the Emperor, whilst technically being the overlord of everyone as a son of heaven, was also just a figurehead, whose position and finances relied entirely on the goodwill of the Hojo. Successive Emperors accepted this situation with varying degrees of good grace, concluding that comfortable irrelevance was better than uncomfortable exile.

Hojo power, however, became a double-edged sword; as their power grew, so did their arrogance. They began to rely on an increasingly small pool of retainers to fill powerful positions, and this led to disillusionment amongst other Samurai houses, who saw their path to wealth and influence blocked by entrenched Hojo interests.

This situation worsened in the aftermath of the Mongol Invasions. Despite successfully defending the country, the cost of mounting the defence had been ruinous to Hojo finances, and the expected rewards of land and titles were not forthcoming (the Samurai didn’t fight for honour, you see.)

This brewing resentment took time to reach a boiling point, but as the 14th century went on, anger towards the government in Kamakura continued to grow, and the Hojo, in what they believed to be an unassailable position, were practically blind to it.

In 1318, Emperor Go-Daigo took the throne. His choice of name was significant, as it had been Emperor Daigo (the Go prefix means ‘later’) who had successfully opposed the power of the Fujiwara during the Heian Period, and Go-Daigo intended to emulate his namesake, and overthrow the Shogunate and restore independent Imperial Rule.

Go-Daigo’s plans were first uncovered during the so-called Shochu Incident in 1324, where comrades of the Emperor were arrested after being accused of plotting against the Shogun. In response, the Emperor sent a letter to the Shogun, ‘ordering’ them to find the real culprits. It is generally believed that the Shogunate were well aware of Go-Daigo’s involvement, but, wanting to avoid a direct conflict with the Court, they played along, and several conspirators were exiled, whilst the Emperor himself remained officially blameless.

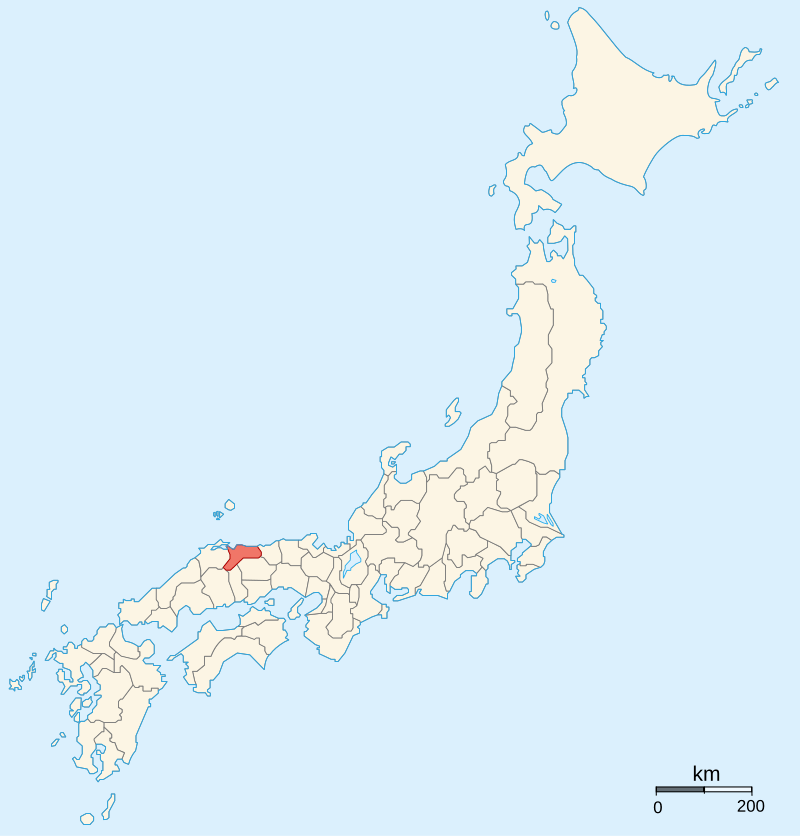

Go-Daigo, though, didn’t learn his lesson, and tried again in 1331; he gathered supporters and retainers, evidently planning to launch a coup against the Shogunate. Once again, his plans were discovered, and the Shogunate dispatched forces to Kyoto to put the planned uprising down. Go-Daigo fled, but was captured shortly afterwards and exiled to the remote Oki Islands (off the coast of modern Shimane Prefecture).

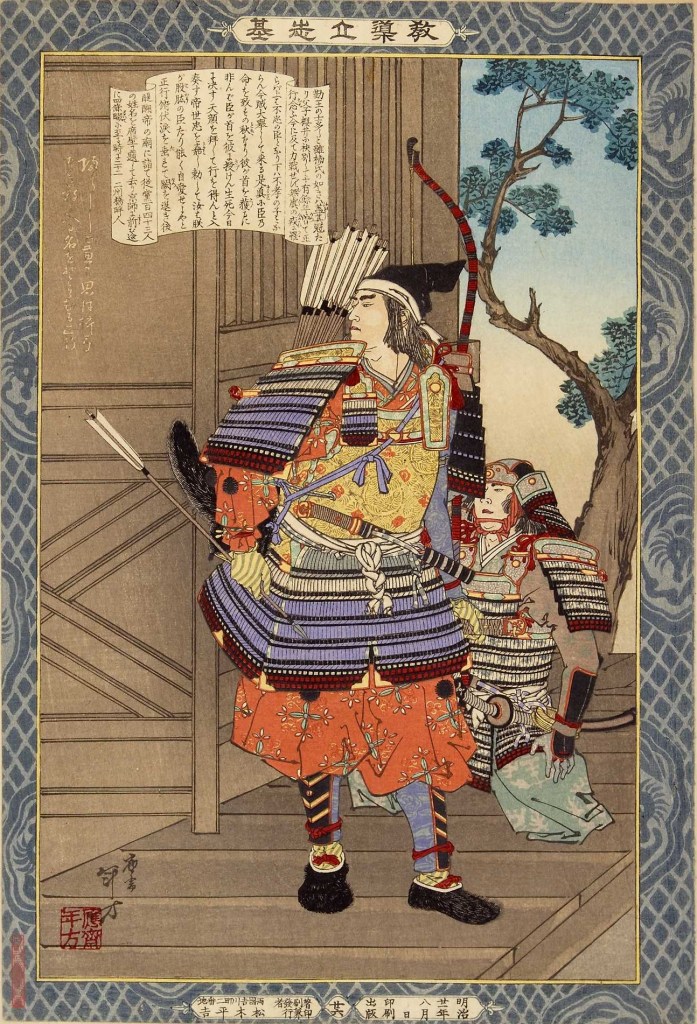

The Hojo replaced Go-Daigo with Emperor Kogon, but partisans of Go-Daigo, including his son, Prince Morinaga (sometimes called Moriyoshi) and legendary Samurai, Kusunoki Masashige, continued to oppose the Shogun, until 1333, when Go-Daigo escaped from exile.

Landing in Hoki Province, Go-Daigo made his base at Mt Senjo and gathered a new “Imperial” Army. In April, Go-Daigo won the Battle of Mt Senjo, gaining him support of many powerful warlords in Western Japan, allowing him to march on Kyoto and take the city in June, re-establishing himself as Emperor.

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1682393

The Hojo dispatched Ashikaga Takauji, one of their foremost generals, with orders to crush Go-Daigo and reassert Shogunate power. Takauji marched, but for reasons that are still unclear, he switched sides, turned his army around, and launched an attack on Kamakura. One possible reason for Takauji’s defection is that the Ashikaga Clan were descendants of the Minamoto, the family that had established the Shogunate, and he hoped to be named Shogun himself, but his real reasons will probably never be known for sure.

Deprived of their main army, the Hojo suffered a series of defeats, culminating with the Siege of Kamakura in July 1333, where the Hojo were surrounded, and would eventually commit mass suicide in a cave behind the Tosho-ji Temple in Kamakura, bringing their power and their family to an end.

In the aftermath of Go-Daigo’s victory, he almost seemed to go out of his way to piss away the goodwill he had accumulated in the years leading up to the so-called “Kenmu Restoration”. The problems stemmed from the fact that those who had supported the overthrow of the Shogunate had done so for a variety of reasons, ranging from genuine loyalty to the Emperor to an ambition to replace the Hojo as regents.

Commoners hoped for land reform, and though there is little evidence of specific goals, it has been speculated that they were hoping for something akin to land redistribution, ending the peasant’s reliance on powerful, and often fickle, landlords.

The Samurai who had fought for the Emperor sought rewards in land and titles, hoping to replace the governors and administrators put in place by the Shogunate.

Finally, Imperial Courtiers hope for a true return to Imperial Rule, where the whole nation was under their control, and they could get back to the good old days of poetry, fancy clothes, and absentee landlordism.

In the end, all three factions were to be disappointed. Go-Daigo, like the proverbial dog chasing a car, didn’t know what to do with power once he’d got it, beyond a vague notion that he should be in charge.

In the first place, the commoners were never likely to get land reform; the Emperor had relied on the land-owning Samurai to do the fighting for them, and they were (unsurprisingly) likely to get on board with sharing the land that they had come to view as rightfully theirs.

So what about the land taken from the Hojo and their allies? Well, that might have gone to the Samurai who had fought for the Imperial cause, but instead, Go-Daigo either took it for himself, or else gifted it to courtiers and cronies, alienating the Samurai who had expected a reward for their efforts.

Finally, we have the Emperor and his courtiers. For whatever reason, they seemed to believe that they could just rule without the Samurai, despite all evidence telling them otherwise. Positions in regional governance, which had been the domain of Samurai for nearly 300 years at this point, went instead to courtiers.

Quite what he had thought was going to happen isn’t clear, but within two years, the Emperor had managed to alienate just about everyone, so it should come as no surprise that his position soon became extremely precarious.

Ashikaga Takauji, the man whose defection had proved essential to the ultimate Imperial victory, now emerged as the leader of the Samurai opposition to the Emperor. The problem started when Takauji began appointing governors to Provinces himself, ignoring Imperial instructions.

This was exactly how the first Shogunate had gotten started, and it wasn’t long before the Imperial court rightly guessed what Takauji was up to. In response, the Emperor named his son, Morinaga, Shogun, a move which further antagonised the already restless Samurai, as the title of Shogun, even before it became a powerful political position, had always been awarded to a member of the military class.

Takauji doesn’t seem to have considered himself a turncoat in this case; the Ashikaga were descendants of the Minamoto, after all, so he portrayed himself as the redeemer of their power and, by extension, the power of the warrior class, earning himself the respect and loyalty of the disaffected Samurai.

Prince Morinaga continued to be the leader of the opposition to Takauji, and so Takauji had him arrested on some flimsy pretext and transported to Kamakura. The situation there was tense, with Hojo loyalists launching sporadic, often poorly organised revolts, until the summer of 1335 when the son of the last Hojo regent, Tokiyuki, successfully took control of the city.

In fleeing the city, Takauji’s brother, Tadayoshi, had Prince Morinaga beheaded, leaving Kamakura to the Hojo rebels. Upon hearing the news of the city’s fall, Takauji asked the Emperor to bestow the title of Shogun on him, to give me the authority to crush the rebellion and restore order. The Emperor refused, guessing correctly what Takauji was up to.

Takauji raised an army and took Kamakura back anyway, and when he was ‘invited’ to Kyoto to explain himself, he refused. At this point, civil war was inevitable, and both sides ordered all Samurai in the realm to join their side.

Again, it’s not clear exactly what Go-Daigo thought was going to happen, after all, he’d spent five years pissing off just about everyone, so it should have come as no surprise when the vast majority of warriors, and peasants too, for that matter, joined Takauji.

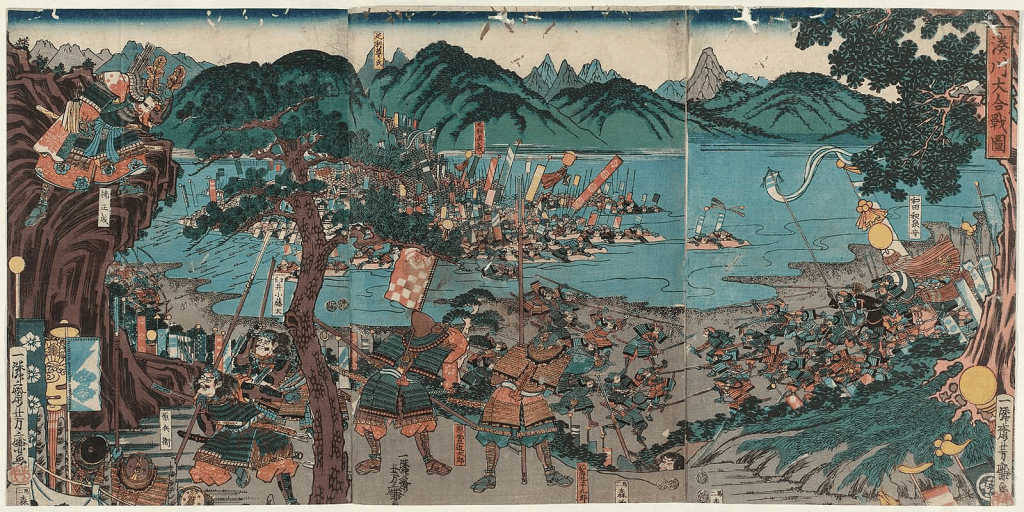

Takauji’s forces quickly secured Kyoto in February 1336, only to be driven out in a counter-attack a short while after. Regrouping in the west, he advanced again, defeating the Emperor’s forces at Minatogawa and securing final control of the capital in July.

Not long after, Takauji had the new Emperor, Komyo, declare him Shogun, giving birth to the Ashikaga, or Muromachi Shogunate. Go-Daigo was down, but not out, however, and he would return to plague the new government, but more about that next time.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%BB%BA%E6%AD%A6%E3%81%AE%E6%96%B0%E6%94%BF

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%AD%B7%E8%89%AF%E8%A6%AA%E7%8E%8B

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%A5%A0%E6%9C%A8%E6%AD%A3%E6%88%90

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kusunoki_Masashige

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_Moriyoshi

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AD%A3%E4%B8%AD%E3%81%AE%E5%A4%89

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genk%C5%8D_War

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kenmu_Restoration