As we discussed last time, Japan in the 1460s was a chaotic place. Rival clans engaged in bloody feuds with each other, and it wasn’t uncommon for members of the same families to take up arms against each other in disputes over who was really in charge, taking sibling rivalry to a whole new level.

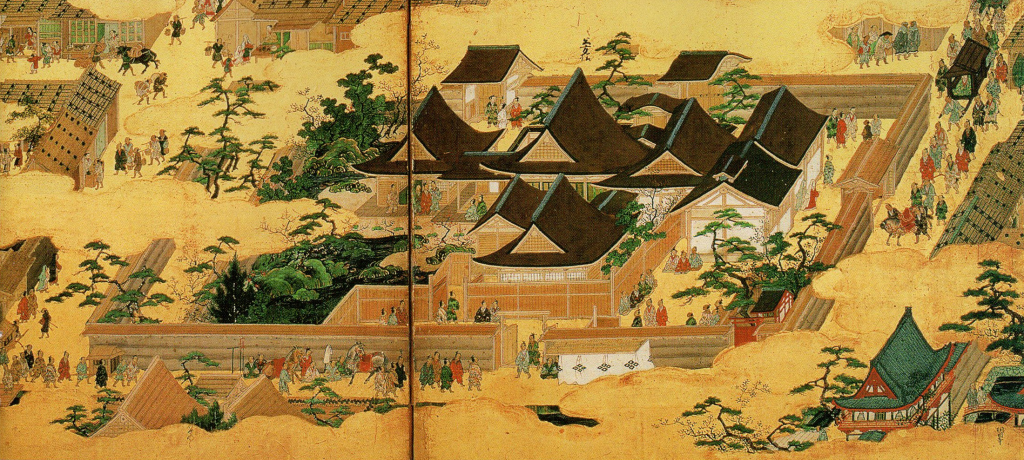

In the centre of this chaos was a Shogun who was so weak he might as well not have existed, and when the violence inevitably reached Kyoto, there was little he could do to stop it.

The exact origins of the Onin War are disputed, but the main rivals were the Yamana and Hosokawa Clans, arguably the two most powerful clans of their day, with both playing key roles in the government and having control of vast swathes of land, and the wealth, manpower, and allegiances that went along with it.

Throughout the 1450s and 60s, the Yamana and Hosokawa Clans had been engaged in something of a ‘Cold War’ in which they supported rival factions in numerous proxy wars around Japan, most importantly, the ongoing civil war within the Hatakeyama Clan.

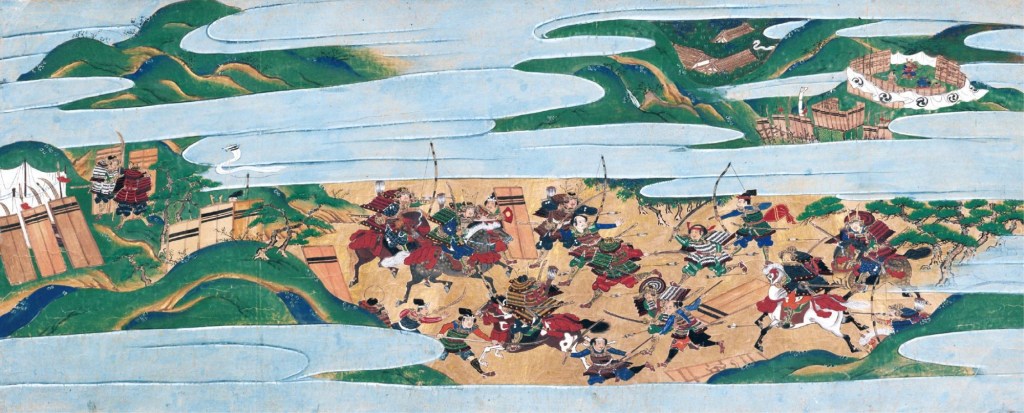

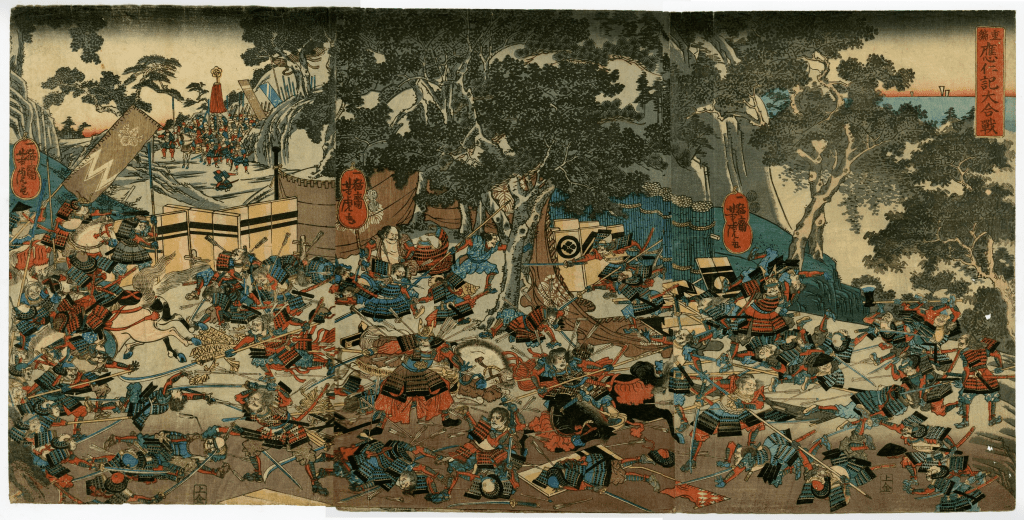

In January 1467, Yamana supported Hatakeyama forces attacked those of the Hosokawa at the Battle of Goryo Shrine (sometimes just called the Battle of Goryo). Though the battle resulted in a Yamana victory, the intervention of the Shogun brought an end to the immediate hostilities, and both Yamana and Hosokawa partisans remained in the capital.

It has been speculated that both side were willing to let the Shogun mediate because neither of them was ready for all out war, because through early Spring, forces gathered in and around Kyoto, until May of that year, when it is said in some (probably exaggerated) sources that there were more than 270,000 warriors present, with the Hosokawa having a significant advantage in numbers (160,000-110,000).

Though the Yamana had secured an advantage after Goryo and controlled the Shogun, the Hosokawa did not sit idly by. Their leaders issued orders and summons of their own, and set about raiding Yamana/Shogunate supply lines, and literally burning bridges.

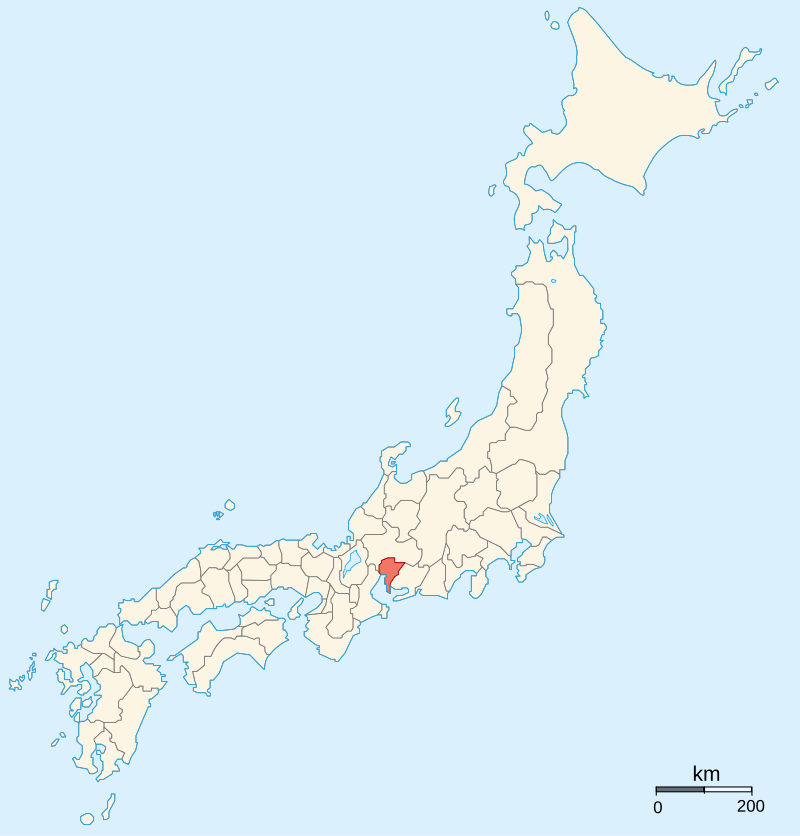

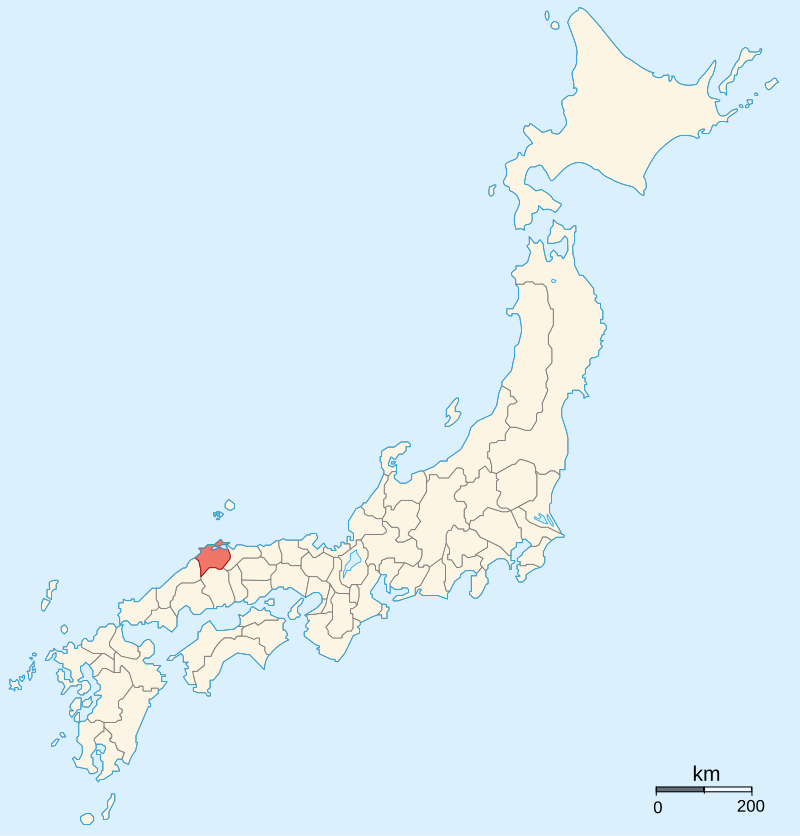

Due to the location of their relative bases in Kyoto, the Hosokawa and their allies became known as the Eastern Army, and the Yamana and theirs were called the Western Army, and it is by these names that we’ll refer to them going forward.

Tensions finally boiled over in late May 1467, when forces of the Eastern Army launched a dawn attack against the Western forces around the Shogun’s palace, driving them away, occupying the palace, and bringing the Shogun under their control.

Shortly after this victory, Ashikaga Yoshimi (the Shogun’s brother, and still heir) was declared commander in chief, and the Shogun himself handed over an official banner to the Eastern Army, proclaiming them to be the official army of the Shogun, effectively branding the Western army rebels.

Despite their setback, the Western forces regrouped and attacked Kyoto in August, driving Yoshimi and his supporters out of the city and establishing control for themselves. It is at this point that the Western Army stopped deferring to any Shogunate officials and instead began issuing orders signed by a ‘junta’ of their most senior generals.

Further attempts by the Western army to press their advantage failed, and several battles throughout September and October ended in bloody stalemate. In December, the Emperor issued a decree stripping all Western generals of their formal Imperial titles in an attempt to further delegitimise their cause; however, it had no practical effect, and as 1467 came to an end, the Western Army was in control of Kyoto, but the war was a stalemate.

Throughout early 1468, there were sporadic outbursts of fighting in and around Kyoto, leaving large areas of the city in ruins, with the two sides gaining and losing ground in return, until the capital they had been so eagerly fighting over was no longer a prize worth having.

In the summer of that year, Yoshimi, who had been in hiding away from Kyoto, was persuaded to return to the capital by his brother, the Shogun. This reconciliation was short-lived, however, as it was becoming clear that the Shogun now supported his (still infant) son, Yoshihisa, as heir. The key leaders of the Eastern Army, too, were behind Yoshihisa, and so Yoshimi fled to Mt Hiei, where, in November, messengers arrived from the Western Army, declaring him to be the ‘new Shogun’. From then on, Western Forces began issuing formal declarations from the ‘Shogun’, Yoshimi, although in reality, the generals remained in control, and Yoshimi was effectively isolated on Mt Hiei.

By early 1469, the conflict had spread to Kyushu and the Kanto as well, where nominally Western and Eastern forces would fight it out in localised episodes of the wider conflict. In reality, however, the complete breakdown in central authority meant that these forces had no loyalty to anyone but themselves, and this fighting is often considered to be the start of the Sengoku Jidai or “Age of the Country at War.”

As 1469 dragged on, the main forces around Kyoto were exhausted. The capital was a ruin, and the Shogunate’s power, already tenuous, had ceased to exist entirely. There had been many reasons for the outbreak of war, but the main one had been control of the Shogunate; now that there was no real Shogunate to control, neither side had much motivation to continue fighting.

Docsubster – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=63970510による

As Machiavelli said, though “Wars begin when you will, but they do not end when you please,” and the Eastern and Western forces were now discovering how true that was. Although superficially a conflict over the Shogunate, by 1470, factions on both sides had begun working for themselves. There were numerous internal conflicts, feuds, and defections, and by 1471, there were several clans that had switched sides, and some that had done so more than once.

In 1472, there was a serious effort to make peace, with the leaders of the Yamana and Hosokawa clans (the originators of the feud) agreeing, in principle, to return to the antebellum situation. These terms were unpopular with other factions, however, many of whom had gained significant territories as a result of the war. The head of the Yamana Clan even went so far as to attempt suicide, in a move that historians have suggested shows the extent of his desire to find a settlement, but it did no good, and the fighting dragged on.

By Mt0616 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=99587678

At the Shogunate court, a priest commented:

“The affairs of the nation were being handled, the maids were planning (all the politics of the nation were being planned by Tomiko, a woman), the Shogun (Yoshimasa) was drinking sake, and the feudal lords were wearing dog hats (a reference to a kind of hat worn during mounted archery displays) . It was as if the world was at peace.”

This quote gives us the impression of a court completely out of touch with the wider world, and indeed, other sources state that Yoshimasa’s drinking was no mere social tipple; he would drink to excess, and it was said that the Emperor got into the habit of joining him, further eroding the respect and prestige of whatever government remained.

In March and May 1473, first the Yamana, then the Hosokawa Clan heads died, and a new generation took their place. Also in that year, Shogun Yoshimasa retired as Shogun, handing the title over to his nine-year-old son, Yoshihisa, whilst keeping the actual power for himself.

Peace was finally agreed between the two main protagonists in April 1473, but the war didn’t come to an immediate end; defections and skirmishing continued, and it wasn’t until 1477 that the Western Army was formally disbanded. In November of that year, the Shogunate held a formal celebration, announcing the restoration of peace.

Despite eleven years of Civil War, very little had actually been achieved. Yoshimasa had remained Shogun and handed the title to his son, Yoshihisa. The rival claimant, Yoshimi, had fled into exile but was formally pardoned in 1478, along with most of those who had supported him.

Early in the war, the Eastern forces had been granted a banner from the Shogunate, effectively declaring themselves the legitimate party, whilst their Western enemies were branded rebels. In the wake of their victory, then, you might have expected the Eastern leadership to seek ‘justice’ (or more likely, revenge) against the Westerners.

So why didn’t it happen?

The answer is fairly simple: the Eastern Army, now just the Shogunate, was too weak. Eleven years of Civil War had resulted in nothing but fatally weakening both sides, and even though they were victorious, no one amongst the Shogun’s supporters had the strength to mete out any kind of justice.

This weakness is best seen in the fact that, despite a formal peace agreement, the fighting didn’t end. Kyoto was a blackened ruin, and the formerly great clans were exhausted, but in the provinces, the war went on, and on, and on.

Though it would not be called the Sengoku Jidai until much later, the Onin War brought about a period of anarchy that would last for more than 120 years, and the Ashikaga Shoguns would never hold any real authority outside of Kyoto, despite some brief resurgences in the late 15th century.

It wasn’t just the Shogunate that was weakened; however, many of the shugo, regional lords, had committed considerable resources to the fighting, expending blood and treasure in pursuit of their goals, only to find themselves with little to show for it. In the 1480s, the system of shugo-in, the policy of requiring the lords to remain in Kyoto, formally broke down, and the shugo returned to their provinces, where some were able to restore their wealth and power, but many others became the first victims of gekokujo, (lit. lower rules/overthrows high) in which deputies of nominally lower rank were able to overthrow their masters, a phenomenon that would become common in the century ahead.

Kyoto itself was also left as a practical ruin by the end of the fighting. The expense of restoring the city and the fact that the Shogun and his wife (Tomiko) were seen as embezzling huge sums of money led to outbreaks of rebellion in the 1480s and only served to further erode what little remained of the Shogun’s authority and prestige.

The Onin War also foreshadowed several developments of the Sengoku Jidai, especially the end of the reliance on Samurai-only armies. The Samurai as a class had once monopolised war, but they were too few to man the much larger armies required in the 15th Century and later. This led to the rise of the Ashigaru, or Foot Soldiers. Originally peasant levies, the Ashigaru would evolve into something that could be recognised as professional soldiery, and they would play a key role in the wars to come, with one of their number, a man who would eventually be known as Toyotomi Hideyoshi, rising to a position of supreme power a century later.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%BF%9C%E4%BB%81%E3%81%AE%E4%B9%B1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E5%B0%9A

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E8%A6%96

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashikaga_Yoshimasa

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E6%94%BF