By 1582, the Shimazu were once again masters of southern Kyushu and had recently defeated the rival Otomo Clan so comprehensively that they effectively ceased to be an obstacle to Shimazu dominance of the whole island. This ambition would be curbed by the intervention of Oda Nobunaga, who wanted to get the Otomo to join his attack on the Mori Clan.

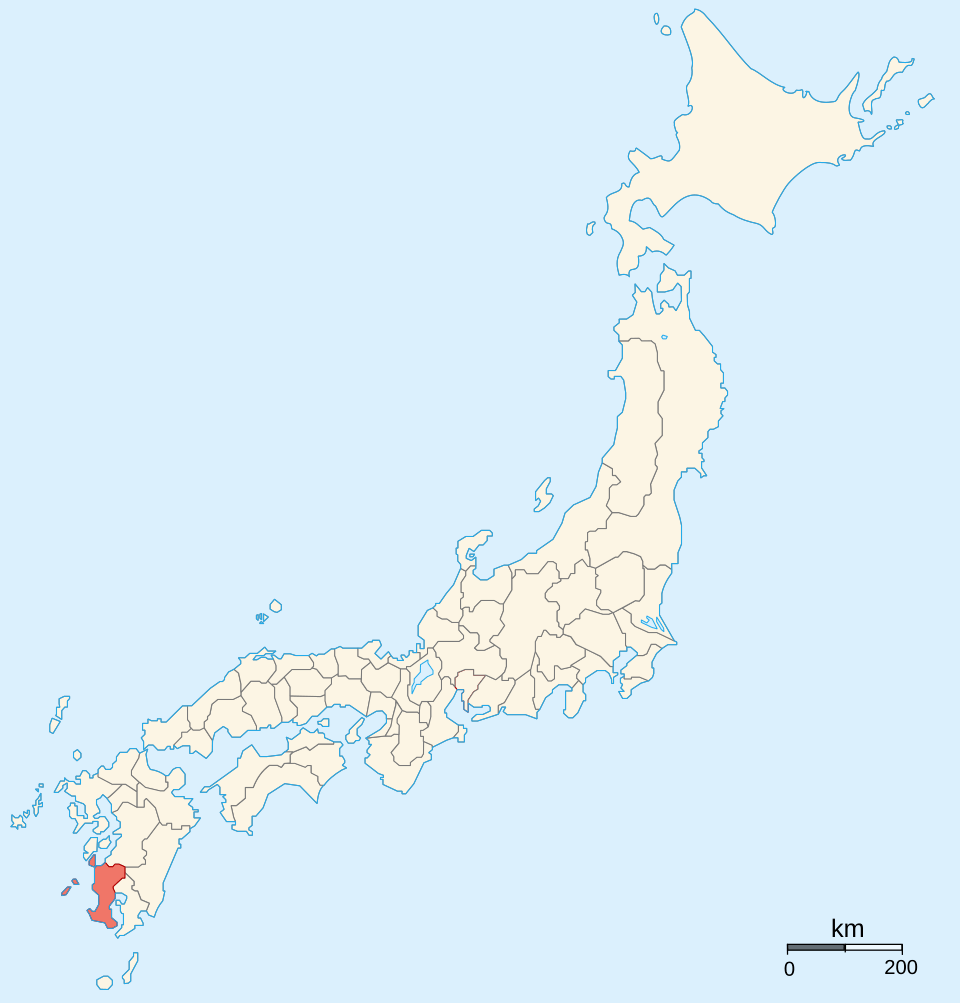

By Alvin Lee – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39198356

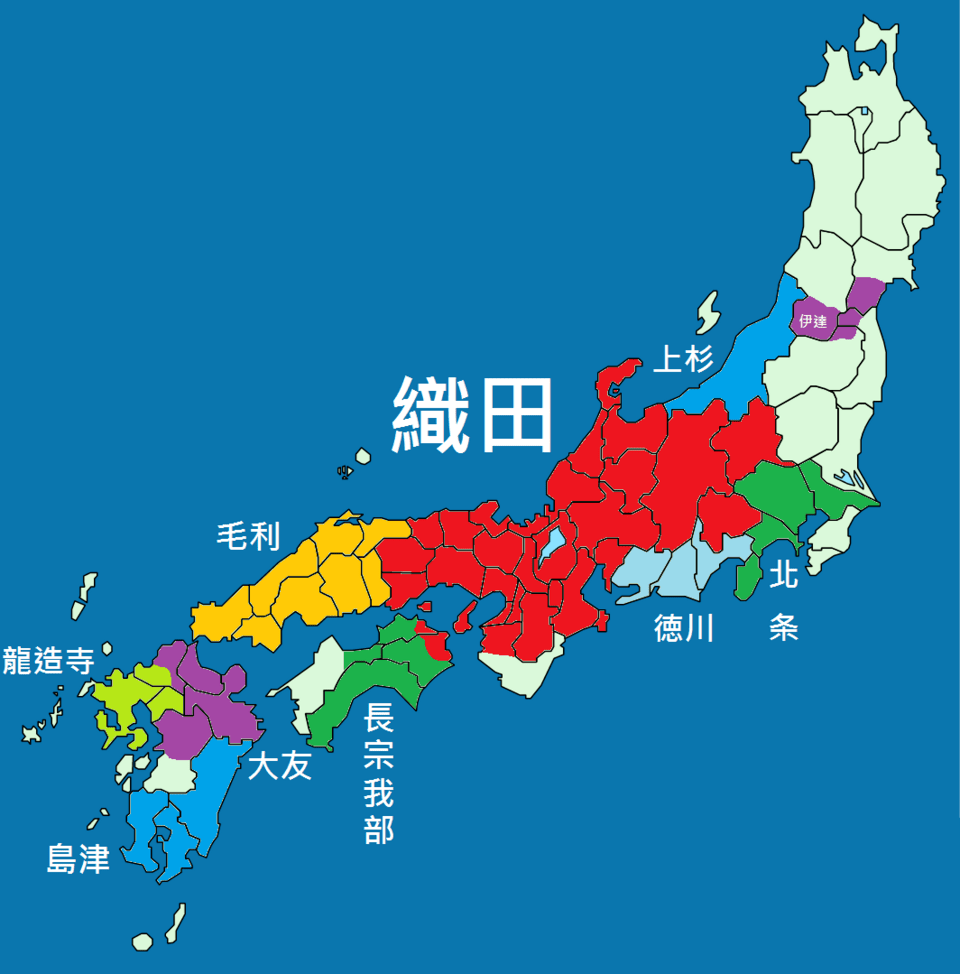

Nobunaga’s plans, along with his life, would be cut short in the Honnoji Incident in June 1582, and the Shimazu once again found themselves as the strongest clan on Kyushu. In the far north-west of the island, close to the modern city of Nagasaki, lay the base of the Ryuzoji Clan. For generations, the Ryuzoji had been a secondary clan in the region. However, under the leadership of Ryuzoji Takanobu, they had expanded their power to control the whole of Hizen Province (modern Nagasaki and Saga Prefectures), and although they had nominally been subordinates of the Otomo Clan, the aftermath of the Battle of Mimikawa in 1578 (which the Otomo lost) gave the Ryuzoji the opportunity to expand even further. (They are in the light-green on the map above).

It was inevitable that the Shimazu and Ryuzoji would clash, and in 1584, a member of the Arima Clan wrote to Shimazu Yoshihisa, requesting his aid against the Ryuzoji. This was a convenient excuse to do what he probably would have done anyway, and Yoshihisa dispatched an army under his brother Iehisa. What followed was a lightning campaign in which the Shimazu, despite being outnumbered more than three-to-one, engaged and defeated the Ryuzoji at the decisive Battle of Okitanawate in May 1584.

This proved to be yet another decisive victory for the Shimazu. Not only did they defeat the Ryuzoji army, Takanobu, but the lord of the clan was also killed, cutting the head off the proverbial snake. The Ryuzoji had expanded rapidly, and their control collapsed just as quickly. Clans who had been forced to submit quickly switched sides to the Shimazu, and any holdouts were destroyed in short order.

In 1586, Yoshihisa turned his attention to the remnants of the Otomo Clan, invading Bungo Province and crushing the final remnants of what had once been Kyushu’s pre-eminent clan. Yoshihisa might have had time to reflect on the fleeting nature of power in that era, but he wouldn’t have had long. No sooner did the Shimazu deal the final blow to the Otomo than the last holdouts of that clan appealed to the new power in Japan for help, Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

By Alvin Lee – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39214208

The Shimazu were at the height of their power, and it is perhaps no surprise that, when Hideyoshi order them to cease their attacks on the Otomo, they refused. Yoshihisa went even further, when he suggested that the Shimazu, and old and storied clan, had no need to accept an ‘upstart’ like Hideyoshi as regent. Hideyoshi had been born a peasant, but he was the most powerful warlord in Japan by that point, and Yoshihisa would come to regret the disrespect.

When it became clear that Hideyoshi meant to invade Kyushu, the Shimazu doubled their efforts to crush the Otomo and secure the whole island. They rightly guessed that any Otomo holdouts would be used by Hideyoshi’s forces as a base for any campaign. Though they would ultimately be unable to fully subjugate the Otomo, the Shimazu’s confidence seemed to have been well placed when, in early 1587, Chosokabe forces, under Hideyoshi’s orders, invaded Bungo province and were heavily defeated at the Battle of Hetsugigawa.

Shimazu celebrations would be short-lived, however. Hideyoshi, reportedly enraged by the ease with which the Shimazu had apparently defeated the initial invasion, mustered a force of between 250,000 and 300,000 men (reports vary), possibly the largest army seen in Japan up to that time. Throughout the spring and summer of 1586, this huge force steamrolled the Shimazu. There were instances of brave resistance, but the writing was on the wall, and in June, the Shimazu sued for peace.

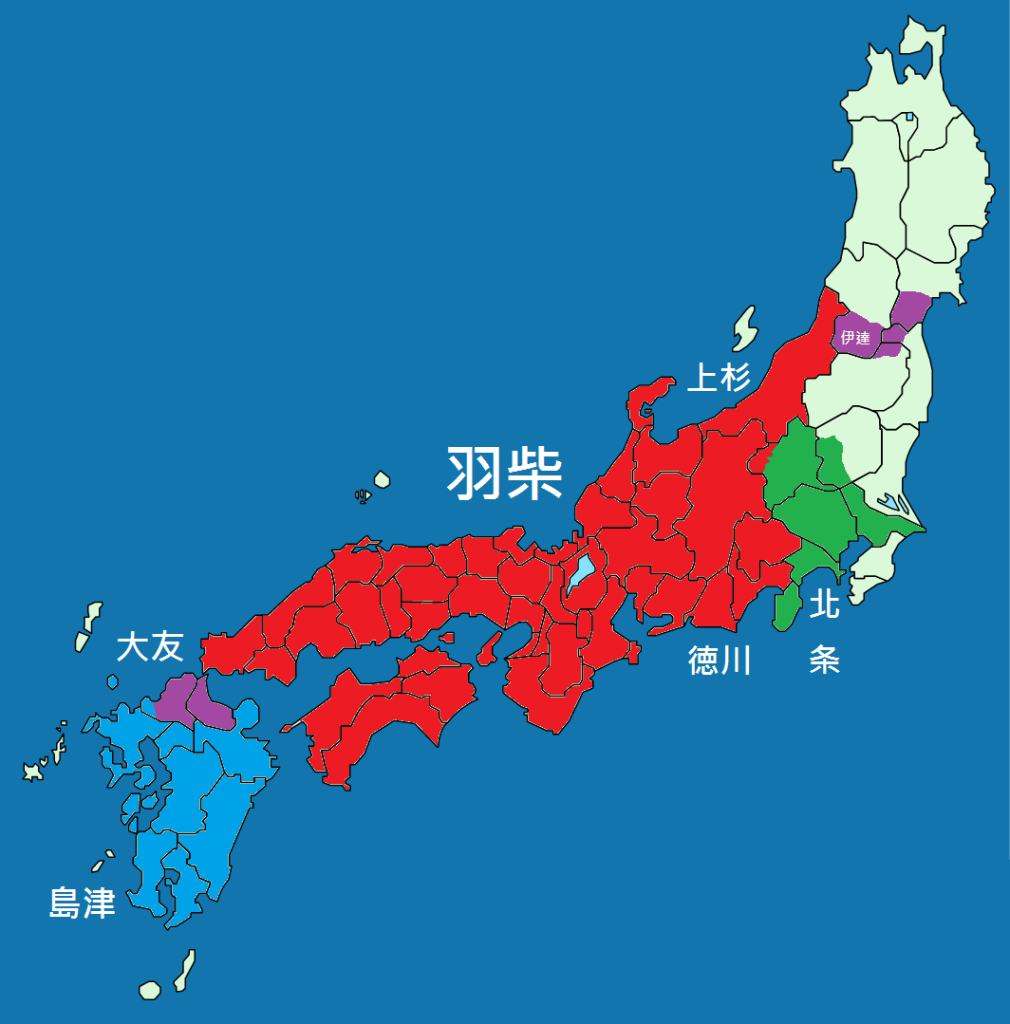

Sakoppi – 自ら撮影, CC 表示 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12570199による

The terms were harsh, but ultimately secured the survival of the clan. Hideyoshi demanded that the Shimazu give up control of almost the whole of Kyushu, essentially wiping out centuries of conquest and expansion. In return, the Shimazu were confirmed as lords of Satsuma province, and later, after further negotiations, Osumi as well.

The Shimazu would prove to be somewhat unreliable vassals. When Hideyoshi invaded Korea in 1592, he ordered all feudal lords to commit troops. The Shimazu were apparently slow to comply with this order, leading Hideyoshi to suspect they were disloyal (which they probably were, having been only recently conquered)

The Shimazu would eventually obey and dispatch troops to Korea, but it appears that Yoshihisa had been replaced as head of the clan in the eyes of Hideyoshi, as formal letters recognising Shimazu control of their provinces were written in the name of Shimazu Iehisa, Yoshihisa’s younger brother, though it appears that Yoshihisa retained the actual power.

Hideyoshi’s death and the end of the war in Korea refocused the realm’s attention back home, as Hideyoshi’s son and heir was just a child. The Shimazu would not be members of the Council of Regents, but when the final rupture occurred in 1600, and war became inevitable, Shimazu Iehisa (nominal head of the clan) was in Kyoto and swore loyalty to the Western (or pro-Toyotomi) army.

This move was apparently not supported by his older brother and the wider Shimazu clan, as when Iehisa requested reinforcements, he received none. This might have been a deliberate ploy by the Shimazu to play both sides, but it’s also possible that an outbreak of fighting in Kyushu caused the Shimazu to focus their efforts closer to home.

The fighting was relatively small-scale and was nominally between supporters of the Toyotomi and Tokugawa Ieyasu (who had just won the decisive Battle of Sekigahara). In reality, this was probably an example of a breakdown in central authority being taken advantage of by local warlords. Unlike in previous eras, however, central control was swiftly reestablished. After his victory at Sekigahara, Ieyasu turned his attention to subduing the rest of the realm, Kyushu included.

A planned campaign against the Shimazu was cancelled in favour of negotiations that lasted nearly two years. Ieyasu suggested that Yoshihisa travel to Kyoto in person, but Yoshihisa always had an excuse not to go; he was ill, the roads were bad, the weather was awful, he hadn’t got enough money, etc. Finally, in 1602, Ieyasu, who apparently had no real appetite for a campaign in Kyushu, confirmed Shimazu control of Satsuma and Osumi Provinces after Yoshihisa’s brother, Iehisa, went to Kyoto in his place (some sources say Yoshihisa actually opposed this idea, only approving it after the fact, when his brother had already departed)

The Shimazu would be largely left in peace in the decades that followed. In 1609, Iehisa, but now more or less dejure lord of the Shimazu, received permission from the Tokugawa to invade the Ryukyu Kingdom (modern Okinawa). This meant that the Shimazu became the only clan to control a foreign kingdom, and meant that, when Japan entered its period of isolation (Sakoku), the Shimazu were one of the few who still had access to the outside world.

These contacts would grant the Shimazu an unusual level of economic strength in the Edo period, and this, combined with some strategic marriages into the Tokugawa, meant that the clan, despite (or perhaps because of) its distance from Edo (modern Tokyo), became one of the richest and most powerful of the era.

This proved to be important in the 19th century, when the irresistible tide of modernisation swept Japan after the first American, but later, other powers sought to take advantage of Japan’s weak position for their own ends. It would be the Shimazu (better known as Satsuma Domain by then) under their leader Nariakira, who were amongst the first to grasp the potential for Western-style industrialisation and warfare.

Satsuma Domain would be at the vanguard of the Meiji Restoration, with its alliance with the Mori clan of the Choshu Domain proving to be the decisive factor in the brief, but bloody Boshin War that saw the Tokugawa overthrown and Imperial rule reestablished.

The Shimazu themselves would endure the tumultuous years of the late 19th and 20th centuries, and the family survives today, with the 33rd head of the clan, Shimazu Tadahiro, serving as CEO of the Shimazu Corporation, which works to promote not only the cultural legacy of the Shimazu family, but also tourism and business development in and around Kagoshima, the traditional heart of the Satsuma Domain.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B3%B6%E6%B4%A5%E7%BE%A9%E4%B9%85

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B3%B6%E6%B4%A5%E7%BE%A9%E5%BC%98

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B3%B6%E6%B4%A5%E6%B0%8F#

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B3%B6%E6%B4%A5%E5%BF%A0%E8%A3%95

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B3%B6%E6%B4%A5%E8%88%88%E6%A5%AD

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B3%B6%E6%B4%A5%E6%96%89%E5%BD%AC

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%A0%B9%E7%99%BD%E5%9D%82%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B9%9D%E5%B7%9E%E5%B9%B3%E5%AE%9A

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%88%B8%E6%AC%A1%E5%B7%9D%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%B2%96%E7%94%B0%E7%95%B7%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%BE%8D%E9%80%A0%E5%AF%BA%E9%9A%86%E4%BF%A1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_daimy%C5%8Ds_from_the_Sengoku_period