As we’ve discussed previously, by the 1490s, the Ashikaga Shogun was a shadow of its former self. The Onin War had effectively ended even the pretence of Shogunate power, and in the provinces, what would later be called the Sengoku Jidai was already underway.

There’s a post on the Onin War if you want details, but very briefly, the war was fought over who would succeed Ashikaga Yoshimasa as Shogun, his son (Yoshihisa), or his brother (Yoshimi). When the war ended in 1477, it was his son who became Shogun.

Yoshihisa was apparently a bit of a lush, and contemporary sources paint him as a young man who was too fond of wine and women. In fact, when he died suddenly in 1489, aged just 25, it was widely blamed on his hedonistic lifestyle (not a bad way to go, mind you).

Despite his proclivities, Yoshihisa died without a male heir, and it was at this point that the son of the defeated brother, Ashikaga Yoshitane, became Shogun. This might seem like a strange choice, and it certainly wasn’t unopposed, but he apparently had the support of Hino Tomiko, Yoshihisa’s mother, who was widely regarded as one of the most influential women in Japanese history.

Quite why Tomiko chose to support Yoshitane isn’t documented, but given her reputation for political intrigue, she probably had some long game in mind. Yoshitane wouldn’t actually become Shogun until July 1490, and even when he took the throne, his position was weak.

There were myriad problems in and around the Shogun’s government, but the fundamental issue seems to have been that Yoshitane was the son of the man who had been defeated in the Onin War just 13 years earlier. The men who had won that war were still in government, and they weren’t fans of the idea of having to serve someone who was probably going to be out for revenge.

When Tomiko announced her support for Yoshitane, several high-ranking members of the government resigned their positions rather than serve under him. Initially, this might not have been a problem. Yoshitane was a young man (just 23) who enjoyed the support of one of the realm’s most powerful figures, Hino Tomiko, and the advice and guidance of his father, Yoshimi, who might have been Shogun himself, if things had gone differently.

Yoshitane was also aided by his kanrei (deputy), Hosokawa Masamoto, an experienced (if slightly eccentric) politician. As seems to be inevitable with the Ashikaga, though, this initial optimism didn’t last. Ashikaga Yoshimi died in January 1491, just months into the new Shogun’s reign, and it seems that his relationship with Hino Tomiko soured too. Some sources (admittedly biased against Tomiko) suggest this was because Yoshitane turned out to be not as compliant as Tomiko had intended, but whatever the reason, Yoshitane was obliged to find a new way to shore up his power.

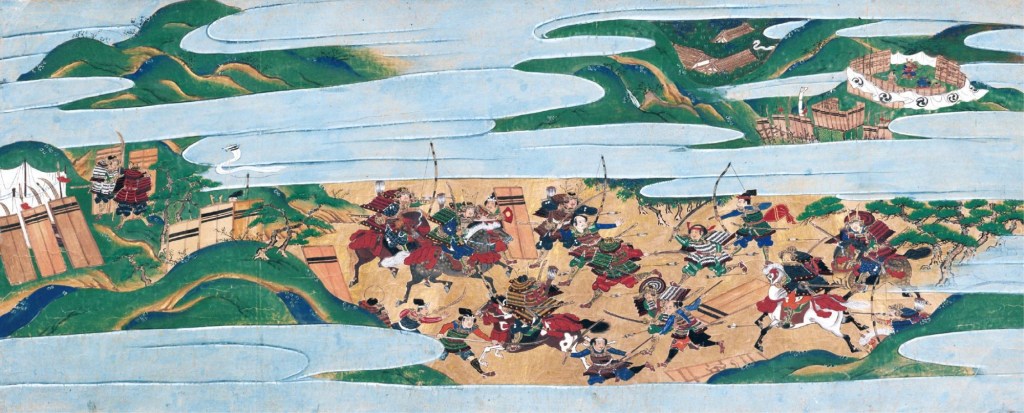

To do this, he turned to the time-honoured tradition of his forebears and went to war. The region around Kyoto had been devastated by the Onin War, and recovery had been unequal at best. There were numerous uprisings from angry peasants and religious movements throughout the decades of ‘peace’, and Yoshitane saw an opportunity to flex his muscles and put these troublemakers in their place.

The first blow was struck against the Rokkaku Clan. Like his predecessors, Yoshitane had few military resources of his own to call on, so he summoned several powerful lords to do the fighting for him. They agreed eagerly, but one figure who opposed the campaign was Hosokawa Masatomo. Quite why the kanrei was against the campaign isn’t clear, but this led to a schism between the Shogun and his most powerful official.

In response, Yoshitane began relying on other lords to do his bidding, attempting to cut Masatomo out of the picture. In 1493, he launched another campaign, this time seeking to bring an end to the division in the once powerful Hatakeyama Clan. This time, Masatomo’s opposition is easier to understand. The Hatakeyama and Hosokawa Clans were historic rivals, and the ‘civil war’ in the Hatakeyama Clan had been to the Hosokawa’s benefit. If the Shogun succeeded in ending the fighting, then the Hatakeyama might regain their strength, and Masatomo couldn’t have that.

When the Shogun issued orders for an army to be gathered in January 1493, Masatomo went to work. He contacted the faction within the Hatakeyama that the Shogun intended to attack and made arrangements with them to earn their support for what came next. Throughout early spring that year, Masatomo gathered others who were unhappy with Yoshitane. Some were partisans of the armies that had opposed Yoshitane’s father; others were disgruntled with the political situation, like Hino Tomiko, who now sided against the man she had supported just a few years earlier.

Others were almost certainly just opportunists, but by April, Masatomo was ready to move. He waited for the Shogun’s army to attack the Hatakeyama in Kawachi Province (in modern Osaka), and when Kyoto was vulnerable, he launched his coup.

It all went relatively smoothly for Masatomo. His forces took the city without much trouble, and Hino Tomiko issued an order commanding that Masatomo take control to restore order, giving his actions the veneer of legality. Masatomo then announced he would depose Yoshitane and replace him with Ashikaga Yoshizumi, who had been adopted by Hino Tomoki and Shogun Yoshimasa.

Geneast – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21645552による

When the news reached the army in Kawachi, it disintegrated almost immediately, with many vassals supporting the new Shogun and effectively legitimising Masatomo’s coup. Yoshitane could still call on around 8000 loyalists to fight for his cause, but the situation was dire.

As well as Yoshitane’s (much reduced) loyalists, the Emperor himself was apparently against the coup. You may remember that the Shogun was technically a servant of the Imperial Court, and although it had been centuries since the Emperor had actually had the power to decide who would be Shogun, the idea that someone else could overthrow him was an affront to what remained of Imperial prestige.

The Emperor was so angry that he even threatened to abdicate, but the impotence of his position was highlighted when Imperial officials pointed out that a) even if he abdicated, the coup would not be reversed, and b) the Imperial Court couldn’t afford the ceremony, and might have to resort to borrowing money for it from the very Shogunate they sought to protest.

So the Imperial Court prevaricated by engaging in some religious ceremonies that the Emperor was required to attend, and would therefore be unavailable to condone or condemn the coup. This led to a strange stalemate, where the Imperial Court could do nothing to change the course of events, but the Shogunate (controlled by Masatomo) could not compel the court to obey, denying the coup the full support of Japan’s ‘legal’ sovereign.

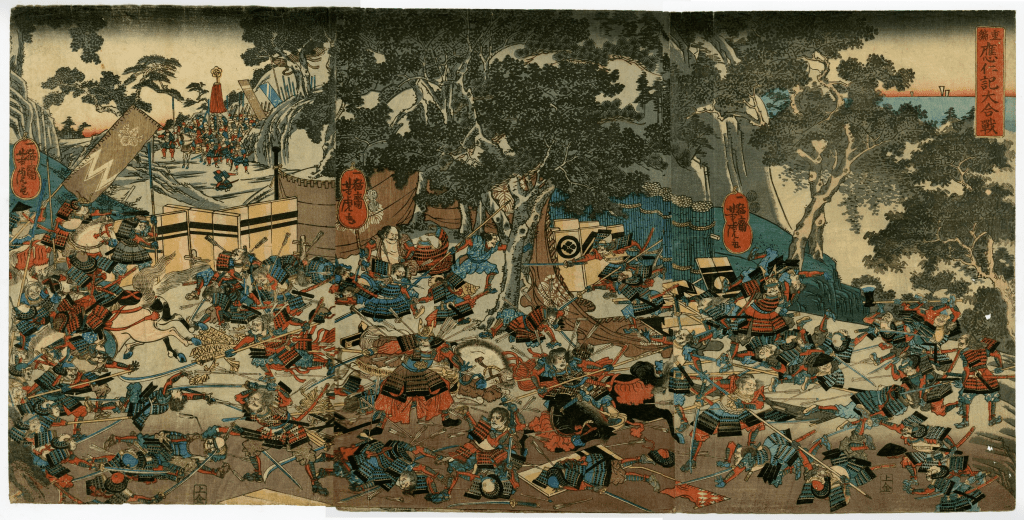

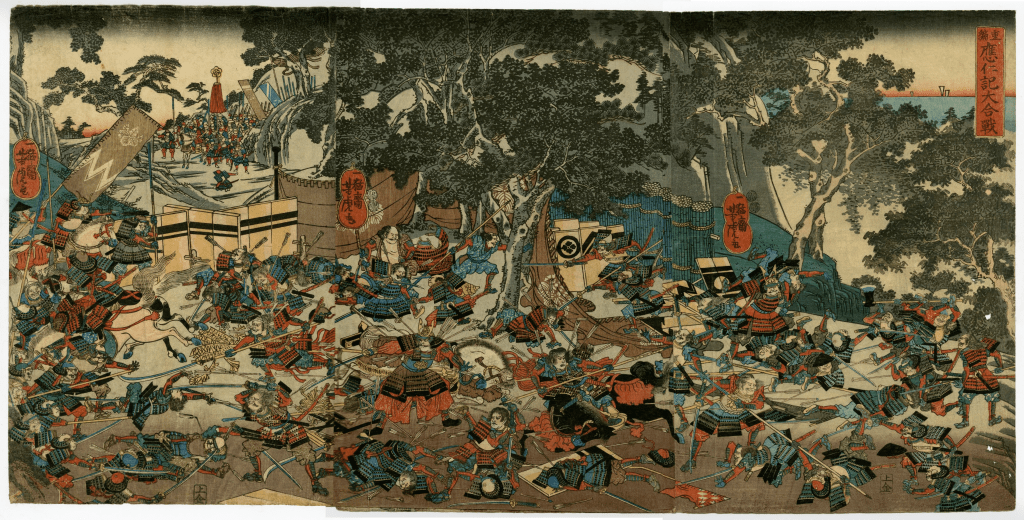

Political difficulties aside, the reality was that Masatomo was now in control, and to demonstrate this, he ordered an army to be dispatched to Kawachi Province to deal with what was left of the old Shogun’s loyalists. Chronicles at the time suggest the force was as large as 40,000, and, faced with such odds, Yoshitane and his supporters retreated to and fortified a nearby temple, where they hoped to hold out.

The situation got worse for Yoshitane, however, as a relief force sent by his supporters met Masatomo’s army near Sakai (modern Osaka), where they were defeated, effectively ending any chance Yoshitane had of reversing the coup.

Not long afterwards, Masatomo’s forces attacked the temple and quickly overwhelmed its defences. Several of Yoshitane’s prominent supporters committed suicide, but Yoshitane himself was captured and taken back to Kyoto and held at the Ryoanji Temple.

663highland – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=159351811による

In the aftermath of this battle, Masatomo had several of his more powerful opponents killed or exiled, and consolidated power in the capital and by the Autumn of 1493, his position was practically unassailable.

Quite why Masatomo decided to get rid of Yoshitane has been debated from the start. The man himself claimed it was due to the Shogun’s military campaigns putting an unsustainable burden on the more powerful lords, and while there’s probably some truth to that claim, it also seems likely that the relationship between Masatomo and the Shogun had broken down, and Masatomo decided to strike while he was in a position of strength.

That being said, Masatomo wouldn’t have succeeded if he’d acted alone. The fact that he had the support of Hino Tomiko and that most of Yoshitane’s supporters abandoned him almost immediately suggests that the dissatisfaction with his rule ran deep. It has also been suggested that Tomiko herself was the instigator of the coup, as she had come to regret her earlier decision to support Yoshitane.

Although the Meio Coup left Masatomo as the dominant political figure in Kyoto, in the long term, it did nothing to reverse the catastrophic decline of Shogunate power. Although the supreme military power, Masatomo, did not have control of the bureaucracy, which remained with Hino Tomiko and her supporters.

Additionally, the swift collapse of the Shogun’s ‘loyalists’ demonstrated how fragile that system really was, and after the coup, instead of relying on several powerful clans, the Shogunate was forced to rely on one, the Hosokawa and by extension, Masatomo.

Masatomo certainly didn’t have it all his own way, then, and the situation only got worse when Yoshitane (who had been left alive) escaped captivity in Kyoto and fled to Etchu Province, from where he issued calls for his supporters to deal with Masatomo.

Masatomo would dispatch an army to deal with Yoshitane, but it was defeated, and not long after that, several powerful clans declared their support for the deposed Shogun, though in reality, they offered little practical support in the short term.

Internally too, opposition to Masatomo grew as Yoshizumi, who had been a boy when Masatomo installed him as Shogun, grew into a man (as they do) and began trying to assert control of what was supposed to be ‘his’ government, so, despite the success of his coup, Masatomo found himself with problems on all sides, and the power of the Shogun declined further still.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%97%A5%E9%87%8E%E5%AF%8C%E5%AD%90

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%98%8E%E5%BF%9C%E3%81%AE%E6%94%BF%E5%A4%89

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E5%B0%9A

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E8%A6%96

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%B4%B0%E5%B7%9D%E6%94%BF%E5%85%83

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E6%BE%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A0%BA

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%BE%8D%E5%AE%89%E5%AF%BA

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%BE%8C%E5%9C%9F%E5%BE%A1%E9%96%80%E5%A4%A9%E7%9A%87