Much like Takeda Shingen, Kenshin’s real name wasn’t Kenshin, but Kagetora, with Kenshin being a religious name given in later life. However, as this is the name he is best known by, we will be referring to him as it throughout.

If you live your life in such a way that you earn the nickname ‘Dragon of something’ and have followers who think of you as an avatar of the God of War, then I’d say you’ve done pretty well for yourself. By this standard, our subject for today, Uesugi Kenshin, is a historical figure worthy of a closer look.

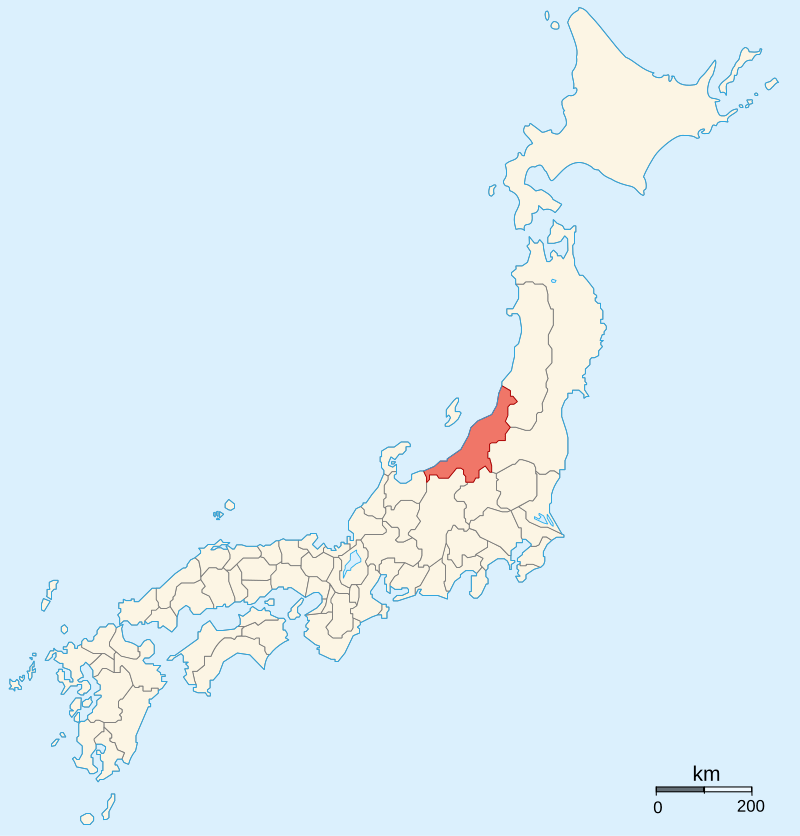

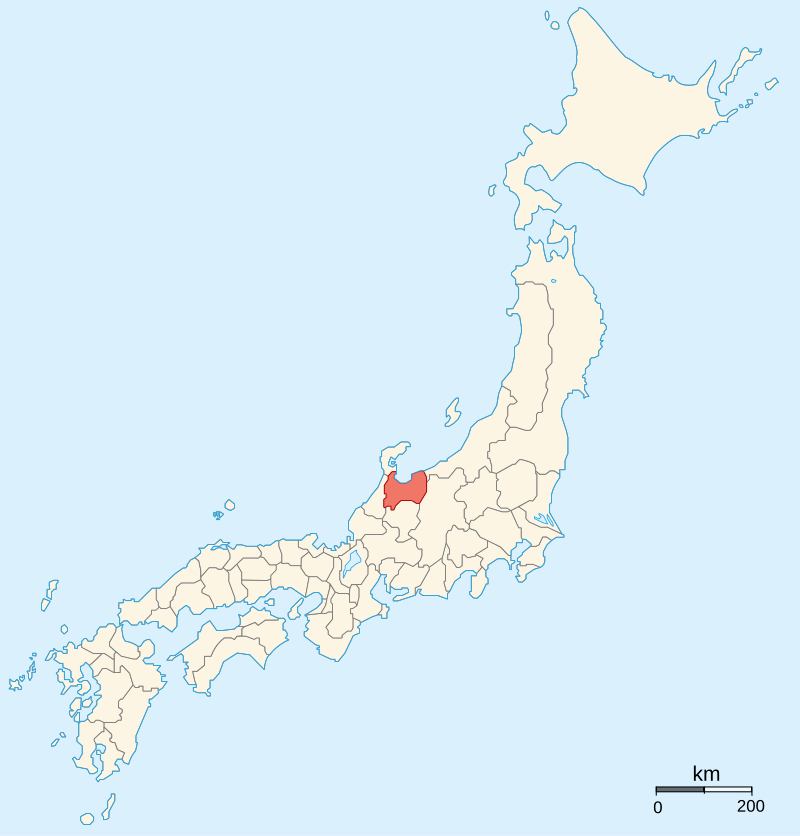

Confusingly enough, Uesugi Kenshin wasn’t actually a member of the Uesugi family to begin with. He was a scion of the Nagao family, a strong clan who were vassals of the Yamanouchi branch of the Uesugi Clan, based in Echigo Province, in what is now Niigata Prefecture.

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1655309

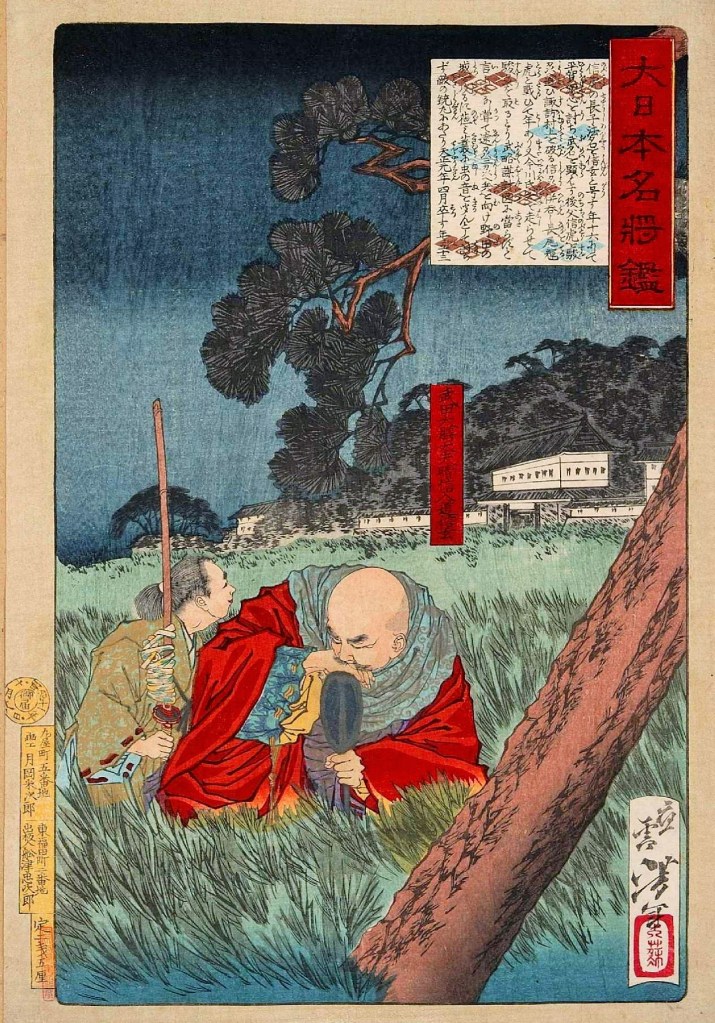

Born in 1530, it is quite likely that Kenshin’s mother was a concubine, and what’s more, the boy himself was the second son. He was never intended to inherit control of the Nagao Clan, and he entered the temple at Risenji at age 11, apparently set on a life as a monk.

He doesn’t seem to have stayed at Risenji for long, however, as when his father died in 1542, just a year later, he was at the funeral with armour and sword at his side, and shortly after that, he was at Tochio Castle when a rebellion against Kenshin’s brother (the new Lord Nagao) broke out. Despite being just 14, Kenshin is supposed to have led the defence of the castle and won his first victory.

At the time, though the Uesugi were nominally the lords of the region, the Nagao served as deputy (and de facto) governors in their place. After the death of Kenshin’s father, it was his elder brother, Harukage, who inherited this position. The brothers don’t seem to have gotten along very well, however, and in the late 1540s, a movement emerged within the Nagao clan that sought to replace Harukage with Kenshin as head of the clan.

nubobo – 栃尾城本丸跡, CC 表示 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=59682349による

Exactly why the clan was so against Harukage isn’t clear, but their efforts were ultimately successful. In 1548, under mediation from Uesugi Sadazane (their nominal overlord), Harukage agreed to adopt Kenshin, then retire as head of the clan, clearing the way for Kenshin to become head of the Nagao Clan aged just 18 or 19 (depending on the source).

In 1550, Sadazane died without an heir, leaving Echigo Province without a lord. At this point, Shogun Ashikaga Yoshiteru instructed Kenshin to take the position of shugo of the province, effectively making him the new lord. Shogunate recognition was not quite the prestigious thing it had once been, however, and not long after this, supporters of Kenshin’s brother rose up in rebellion against him.

Kenshin quickly bottled up the rebels at Sakado Castle, when the castle fell, the leader of the rebels was spared because he was Kenshin’s brother-in-law, and following this, Kenshin, still aged just 22 had established effectively control over the whole of Echigo Province.

Looking back for a moment, five years earlier, the Uesugi Clan (or more accurately, the Ogigayatsu branch of the clan) had been defeated at the Battle of Kawagoe by the new rising star of the Kanto, the Hojo Clan. The Ogigayatsu-Uesugi were wiped out after this battle, leaving only the Yamanouchi Branch of the clan. In 1552, Uesugi Norimasa, who was, on paper, the Kanto Kanrei (Shogun’s deputy) was finally driven out of the Kanto entirely and sought refuge with Kenshin.

Unsurprisingly, harbouring their enemies didn’t do much for the relationship between Kenshin and the Hojo, and Kenshin would send an army to oppose the Hojo’s invasion of Kozuke Province (modern Gunma Prefecture), capturing Numata Castle, and forcing the Hojo to retreat.

A year later, Kenshin would face a new enemy, as Takeda Shingen’s long-running invasion of Shinano eventually obliged some of the clans there to flee and seek refuge with Kenshin in Echigo. Much like the Hojo, the Takeda didn’t take kindly to someone giving refuge to their enemies, and one of Japanese history’s most famous rivalries was born.

In August 1553, an army led by Kenshin himself advanced against the Takeda in Shinan, defeating Shingen himself at the Battle of Fuse on August 30th, then again at Yuwata on September 1st. After this, Shingen adopted a strategy of avoiding direct battle with Kenshin, and the conflict settled into a stalemate that was later called the First Battle of Kawanakajima.

日本語版ウィキペディアのBlogliderさん – 原版の投稿者自身による著作物 (Original text: Photo by Bloglider.), CC 表示-継承 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12400636による

In 1554-55, Kenshin was obliged to face a rebellion launched by treacherous vassals in league with Shingen. Putting down the rebellion quickly, Kenshin again marched into Shinano in April 1555 to face the advancing Takeda forces, again led by Shingen.

At the Second Battle of Kawanakajima, the two sides faced each other in another stalemate, which dragged on for five months, before mediation from the Imagawa Clan led to both sides withdrawing after little actual fighting.

In the following year, Kenshin apparently announced he would retire and become a monk, however, another outbreak of Takeda-backed rebellion forced him to change his plans, and after a period of peace, in 1557, Shingen again advanced against Kenshin’s allies in Shinano, forcing him to intervene and leading to the Third Battle of Kawanakajima, which, much like the previous two, swiftly settled into stalemate.

A year later, Kenshin dispatched an army in an ultimately unsuccessful invasion of Kozuke Province and then in 1559 he was ‘invited’ for a meeting with the Shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiteru. Some sources say that Kenshin was granted the title of Kanto Kanrei at this time, the position traditionally held by the Uesugi Clan. He also apparently donated funds towards the maintenance and repair of the Imperial Palace.

It seems that Kenshin enjoyed good relations with the Shogunate, but the already well-established decline of the Shogun’s power is highlighted again when he asked Kenshin, Shingen, and the Hojo to make peace in order to combine their forces against the Shogun’s enemies. All three parties refused.

In March 1560, the Imagawa Clan’s devastating defeat at Okehazama opened the way for Kenshin to intervene directly in the Kanto again, as the Imagawa had been allied to his enemies, the Hojo, and their defeat left the Hojo vulnerable. Later that year, Kenshin launched another large-scale invasion of Kozuke Province, driving the Hojo back and capturing several important castles before celebrating New Year at Maebashi Castle, the gateway to the Kanto Plain.

In March 1561, Kenshin was formally adopted by the Yamanouchi-Uesugi Clan (the only remaining branch) and changed his surname to match. Though he would be known as Uesugi Kagetora from this point, we will continue to call him Kenshin to keep things simple.

In August of that year, Kenshin led another large army into Shinano, and engaged the Takeda at the Fourth Battle of Kawanakajima. Unlike the previous three, this battle was not an extended stalemate, but a bloody one. Both sides suffered heavy casualties, with sources ranging from around 20% losses, to as high as 60 or 70%, and when the battle was over, the Takeda held the field, but made no attempt to intervene as the Uesugi withdrew, leading some to suggest the battle was a bloody draw.

The Takeda and Hojo clans, recognising the Uesugi as their common enemy, renewed their combined efforts and launched a joint counter-attack in Musashi Province in late 1561. At first, Uesugi forces were successful against the alliance, even getting as far as besieging Odawara Castle, the Hojo’s main stronghold, before being forced to withdraw after allied counter-attacks in other parts of the Kanto.

The strategic situation in the Kanto would ebb and flow over the following years, as Uesugi, Takeda, and Hojo armies advanced and retreated, and the local lords would switch sides depending on whoever appeared to be in the ascendancy.

All three factions would be occupied with fighting each other, but also engaged in other battles and proxy wars with allies and supporters of each other’s enemies. For Kenshin, this meant being obliged to dispatch forces into neighbouring Etchu Province in 1568, to deal with Ikko Ikki forces nominally allied with Shingen.

Seeking to take advantage of this distraction, Takeda forces attacked in Shinano and were ultimately defeated, but a rebellion in Echigo (Kenshin’s home province) meant he was unable to take advantage of this victory in the short term.

Later that year, the strategic situation would shift in Kenshin’s favour, however, as the long-term decline in Takeda-Imagawa relations finally led to open conflict between two of his main rivals. The Imagawa would request aid from both the Uesugi and the Hojo, and while Kenshin would refuse, the Hojo dispatched forces to oppose the Takeda, bringing an end to the alliance that had done so much to oppose Kenshin.

However, years of expensive (and bloody) campaigns in the Kanto had left the Uesugi exhausted, and in 1569, Kenshin reluctantly agreed to a peace deal with the Hojo, which saw the Uesugi withdraw from Musashi Province (modern day Tokyo and Saitama) and the Hojo withdrew from Kozuke.

With his borders with the Hojo (relatively) secure, Kenshin was able to focus on campaigning against the Takeda again. In 1570 and 1571, he would engage the Takeda and their allies in Etchu and Shinano Provinces, generally having the better of the fighting, but the situation would shift again in 1572 when the lord of the Hojo, Ujiyasu, passed away, and was replaced by Ujimasa, who made peace with the Takeda, turning on the Uesugi. At the same time, the Etchu Ikko Ikki launched a fresh attack, instigated by Takeda Shingen.

The Ikko Ikki would initially be successful against Kenshin, but by mid-1573, the momentum had shifted back in his favour, and several key fortresses within Etchu were taken. Also in that year, Kenshin’s long-time rival, Takeda Shingen, passed away, an event that apparently caused Kenshin to weep openly, but also significantly weakened the Takeda.

Over the following two years, Kenshin was forced to split his focus between his ongoing campaign in Etchu and the situation in the Kanto. By the end of 1574, the Hojo had effectively ended any Uesugi presence in the region, and although Kenshin would launch counterattacks, the writing was on the wall for Uesugi power in the Kanto.

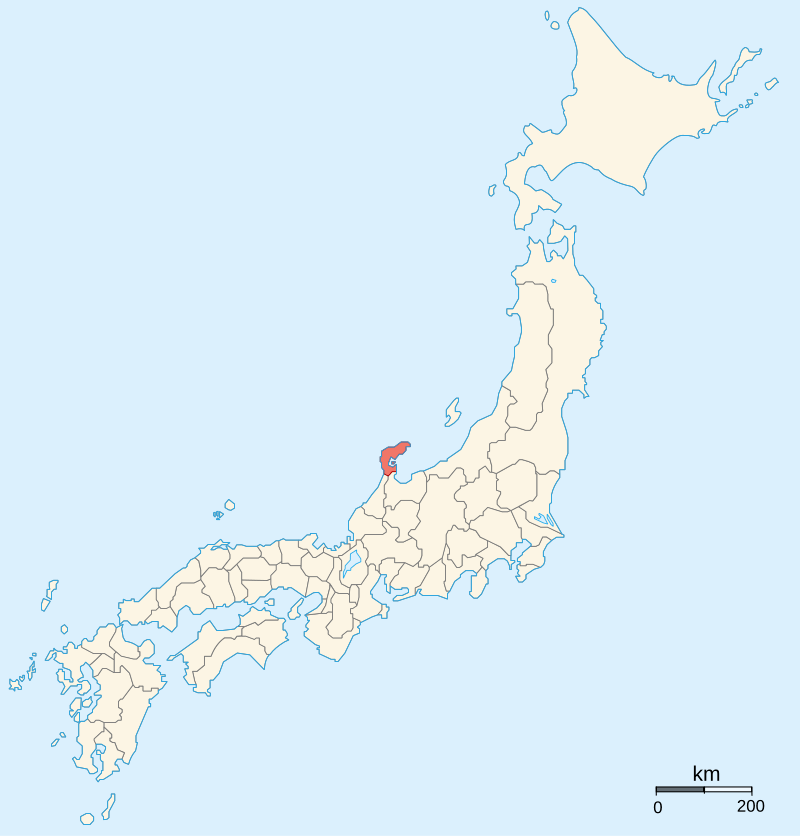

In 1576, Kenshin would receive a request for aid from the Shogun, seeking support against Oda Nobunaga, who now dominated central Japan and had forced the Shogun into exile. In order to get to Kyoto, Kenshin was obliged to focus all his resources on securing Etchu and Noto Provinces. This campaign would drag on throughout 1576 and 1577, delayed by intervention from the Hojo and internal rebellion, but by November 1577, Kenshin had secured control of the provinces and was poised to strike at Kyoto itself.

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1690738

Mustering a large army, Kenshin would march out to meet a force led by Nobunaga’s generals, Shibata Katsuie and Hashiba Hideyoshi (better remembered to history as Toyotomi Hideyoshi), who were not fond of each other. A dispute led to Hideyoshi withdrawing his forces early, and when the two sides clashed at the Battle of the Tedori River on November 3rd, Kenshin would emerge victorious.

The exact course of the battle, and even the size of the forces involved, is not clear from contemporary sources, but Kenshin would withdraw temporarily, issuing instructions for a renewed campaign to begin in the spring. The battle at the Tedori River had opened a strategic opportunity for Kenshin, and it has been speculated that he might have been able to complete his march on Kyoto.

Much like his rival, Shingen, however, Kenshin would never make the march. In early March, Kenshin would collapse (allegedly whilst in the toilet) and fall into a coma from which he would never wake up; he died on March 13th, aged 49.

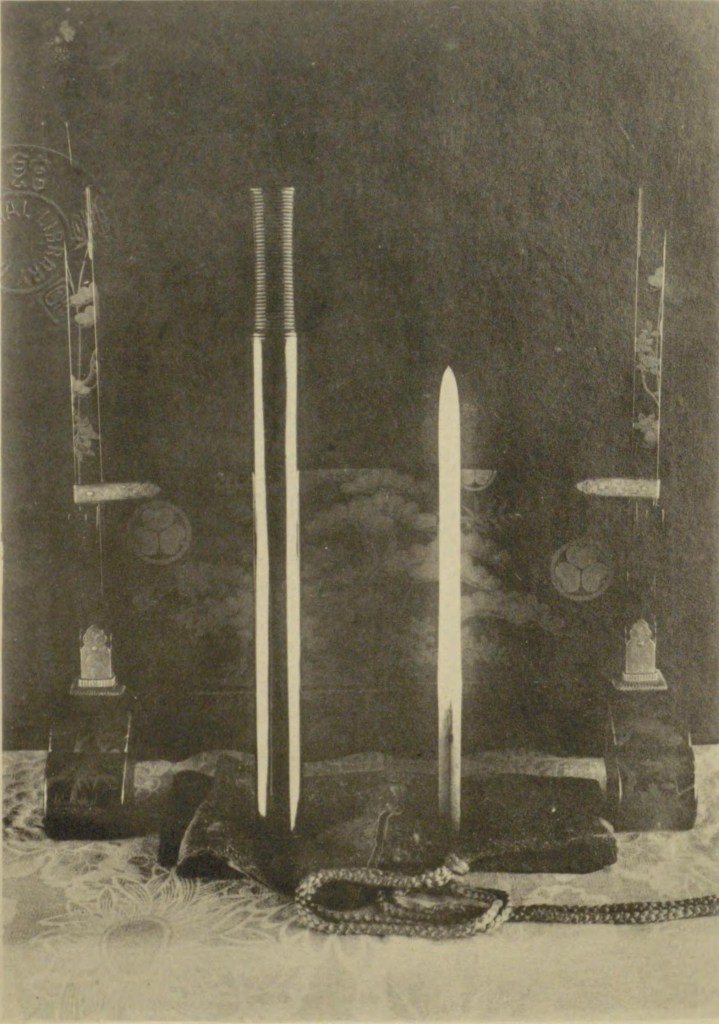

By shikabane taro, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=54071606

Much like the Takeda after the death of Shingen, the Uesugi would be seriously weakened by Kenshin’s death. Though they had been a threat to Nobunaga, Kenshin’s death, and the ongoing effects of years of more or less constant conflict, rendered them powerless to stop the rise of Nobunaga, and after his death in 1582, the Uesugi would make their peace with his successors.

Decisions made at the end of the Sengoku Jidai would see the clan’s star fall even further, though that is a story for another time.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%8A%E6%9D%89%E8%AC%99%E4%BF%A1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%89%8B%E5%8F%96%E5%B7%9D%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Tedorigawa

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B7%9D%E4%B8%AD%E5%B3%B6

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%89%8D%E6%A9%8B%E5%9F%8E

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%B2%BC%E7%94%B0%E5%9F%8E

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battles_of_Kawanakajima