As we mentioned previously, the word Nanbokucho literally means Southern and Northern Court, and it was this division that was the defining factor during the early years of the Ashikaga Shogunate (hence the name, I suppose).

There had been an abortive attempt at reconciliation during the so-called Shohei Reunification, when Ashikaga Takauji (the Shogun) had made a deal with the Southern Court in order to gain their support against his rebellious brother, Tadayoshi.

As we discussed last week, the Reunification fell apart almost as soon as Tadayoshi had been dealt with, as neither side could tolerate the other gaining power. No sooner was Tadayoshi dead than the Northern and Southern Courts went at it all over again.

In the immediate aftermath, Southern forces attacked Kyoto, taking the city, only to be driven out a month later by a Shogunate counterattack, and this didn’t just happen once either. In the period of 1352 to 1361, there were actually four Battles of Kyoto (though they also have other names in Japanese).

Sorasak boontohhgraphy – https://unsplash.com/photos/_UIN-pFfJ7cアーカイブされたコピー at the Wayback MachineImage at the Wayback Machine, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61767016による

Each time, Southern forces would attack, usually taking the city, only to be driven out again shortly afterwards by armies loyal to the Shogun. During this period, with Takauji’s health apparently failing, his son Yoshiakira began to take on more responsibility.

When Takauji died in 1358, Yoshiakira became the second Ashikaga Shogun, and almost immediately set about launching a major military campaign against the Southern Court, seeking to crush it once and for all. Yoshiakira’s forces were able to take Akasaka Castle, home of the powerful Kusunoki Clan (whom we’ve mentioned previously).

Despite this success, the Southern Court, led by the Kusunoki, resorted to guerrilla warfare in the mountainous terrain, and the conflict dragged on to the point that several Shogunate generals defected, or else just went home.

In 1361, buoyed by another defection, the Southern Court once again attacked Kyoto, but once again, they couldn’t hold it, and within a month, the Shogun was back in control of the capital.

This back-and-forth warfare did little but exhaust the resources of all involved, but generally, the Shogun had the advantage. This was further emphasised in 1363, when the powerful Yamana and Ouchi clans (previously supporters of Tadayoshi, and then the Southern Court) submitted to the Shogun.

Meanwhile, everywhere else…

Whilst the Nanbokucho period was violent and chaotic, the direct confrontations between the Northern and Southern courts actually only happened in a relatively small area of central Japan. So what was going on elsewhere in the country?

Well, it wasn’t good. During the Kamakura Shogunate, most of the warrior clans had paid at least lip service to the idea of loyalty to the Shogun, and things had been relatively peaceful. The Ashikaga Shogunate, in contrast, had practically no control outside of the areas of central Japan.

This meant that powerful local warlords in places like the Kanto or Kyushu (Eastern and Southern Japan, respectively) were more or less left to their own devices, though some would side openly with either the Shogunate or the Southern Court.

In Kyushu, for example, local forces, supplemented by warriors sent by both courts, fought a series of increasingly bloody battles, culminating in the Battle of Chikugo River in the summer of 1359. It is said that this battle had over 100,000 combatants, with more men killed (46,000) than during the entire Mongol Invasion. Victory for the Southern Court secured control of Kyushu for more than a decade.

Musuketeer.3 – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27263125による

Elsewhere in Japan, strong central government was replaced by strongman local government, as Shugo, military governors that had once been appointed by the Shogun, now took on the role of hereditary lords, passing their titles on to their heirs and creating a powerful military aristocracy that was capable of enforcing local law and order themselves and saw no need to seek support from a Shogun that might be too distracted to help anyway.

This didn’t happen overnight, of course, the transition towards warrior rule was often gradual, and highly inconsistent across different provinces. The Samurai, who were often little better than thugs in their treatment of peasants, were not popular, and the Shugo quickly learned to lean on the (increasingly obsolete) legitimacy that came from being a “governor” instead of a “lord.”

Technically, each Shugo derived his authority from the Shogun, and by extension, the Emperor. Yes, it was the Shugo’s men who collected the taxes and enforced the law, but he did so in the name of the Shogun. Whether or not anyone actually believed this legal fiction is besides the point; by the 1360s, centralised control of the provinces was breaking down, and it would be centuries before it would be recovered.

Back at home

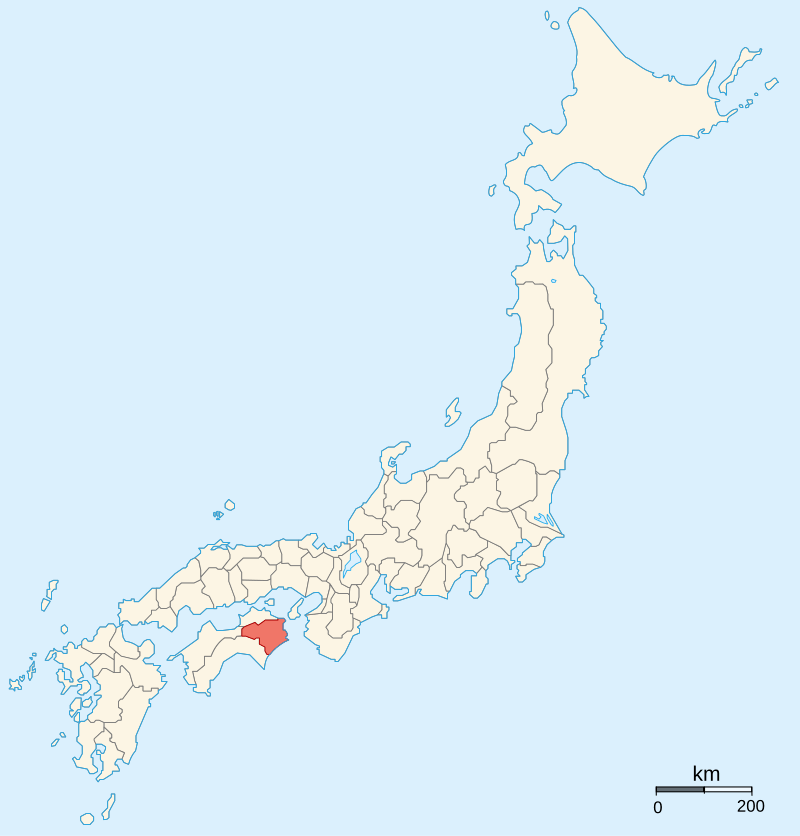

In 1361, Doyo (remember him?) pops up again, orchestrating the downfall of his rival Hosokawa Kyouji. Kyouji, however, wasn’t the type to go quietly, and as a member of the powerful Hosokawa Clan, based in Awa Province (where he fled), he was able to raise a significant army against the Shogun.

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1652119

Like many of those who opposed the Shogun, Kyouji and the Hosokawa sought support from the Southern Court, and together they took Kyoto in December, but within a few weeks, they were driven out. Not long after, Kyouji was forced back to Shikoku, where he would be killed battling forces led by his own cousin.

Despite another victory for the Shogun and the Northern Court, this latest Battle of Kyoto had reinforced the belief that military power alone was not going to be able to settle the issue. Both Shogun Ashikaga Yoshiakira and Emperor Go-Murakami appointed officials who were in favour of peace, and tentative negotiations began shortly afterwards.

This wasn’t a smooth process, mind you. In 1366, the Shiba Clan, former loyalists of the Shogun and strong proponents of peace, were accused of plotting against the Northern Court and exiled. Instead of joining the Southern Court as others had done, the Shiba retreated to their stronghold in Echizen Province (in modern Fukui Prefecture), where they were pursued by Shogunate forces and eventually defeated in July 1367.

As a side note, the Shogun actually ordered several clans to send forces to deal with the Shiba, which they did. While this showed that the Shogun was able to call on considerable support when needed, it also laid the groundwork for later trouble, as it became increasingly clear that the Shogun, and by extension, the Ashikaga Clan, did not have the military strength to enforce policy on its own.

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1655318

The path to peace was also complicated in 1367 by the Southern Court’s insistence that the Northern Court abide by the terms of the (failed) Shohei Unification, which the Shogunate unsurprisingly refused to do. This breakdown in negotiations almost led to a resumption of war, but cooler heads prevailed, and it seemed like things might work out.

Fate has a way of being uncooperative, however. Ashikaga Yoshiakira died suddenly in December 1367, followed in March 1368 by Emperor Go-Murakami. The third Shogun was Yoshiakira’s son, Yoshimitsu, who was still a minor and was thus aided by Hosokawa Yoriyuki (the cousin who had defeated Kyouji back in 1361).

At the Southern Court, Emperor Chokei took the throne. A hardliner, Chokei refused to continue negotiations with the Shogunate that weren’t predicated on the Northern Court submitting completely. This inflexible approach actually worked against the Southern Court’s interests, as several powerful figures who had been in support of peace (including some members of the influential Kusunoki Clan) defected to the Shogun’s side.

And so the war would go on. Hosokawa Yoriyuki would actually prove to be an effective administrator and did much to improve the position of the Shogunate before eventually falling foul of internal politics, but more on that next time.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8D%97%E5%8C%97%E6%9C%9D%E6%99%82%E4%BB%A3_(%E6%97%A5%E6%9C%AC)

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B2%9E%E6%B2%BB%E3%81%AE%E5%A4%89

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%B4%B0%E5%B7%9D%E6%B8%85%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B1%B1%E5%90%8D%E6%99%82%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E8%A9%AE#%E5%B0%86%E8%BB%8D%E5%B0%B1%E4%BB%BB%E5%BE%8C

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashikaga_Yoshiakira

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanboku-ch%C5%8D_period