The formation of the Heian Court was not the story of one family (the Imperial family) asserting its dominance over everyone else. Instead, the Court was made up of several clans, who rose and fell according to the vagaries of fate. You may recall that when the Yamato brought the idea of “Emperor” over from China, they switched the concept of a Mandate of Heaven with that of a literal Son of Heaven. This had the double effect of meaning that the Emperor’s rule was now divinely ordained (handy), and he couldn’t be overthrown and replaced by a new dynasty, as happened relatively frequently in China.

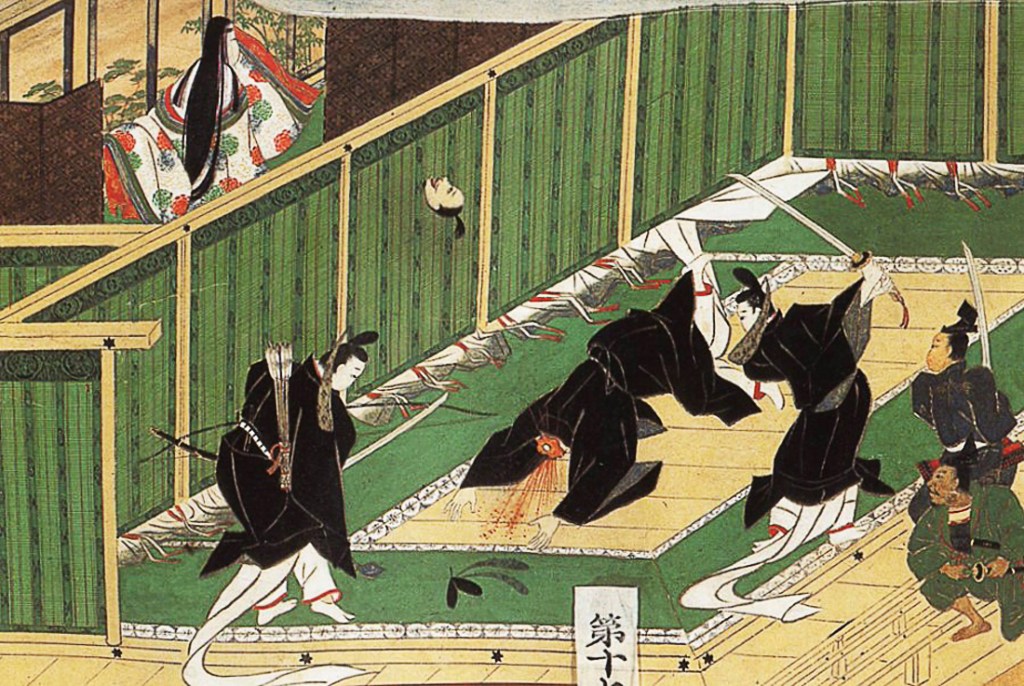

Since the noble families couldn’t take the throne itself, it was controlling the man (or woman) sitting on it that became their objective. There were usually several powerful families at a time, and their rivalries often turned violent, with plots, counter-plots, rebellions, coups, and assassinations all part of the early Imperial political landscape.

By the mid-7th Century, the dominant family were the Soga. Their path to power was fairly typical of the time. Daughters of the clan were married to sons of the Imperial family, and more than one Emperor had a Soga mother. Through these close family ties, the Soga Clan rose to an almost insurmountable position of influence, but it didn’t last.

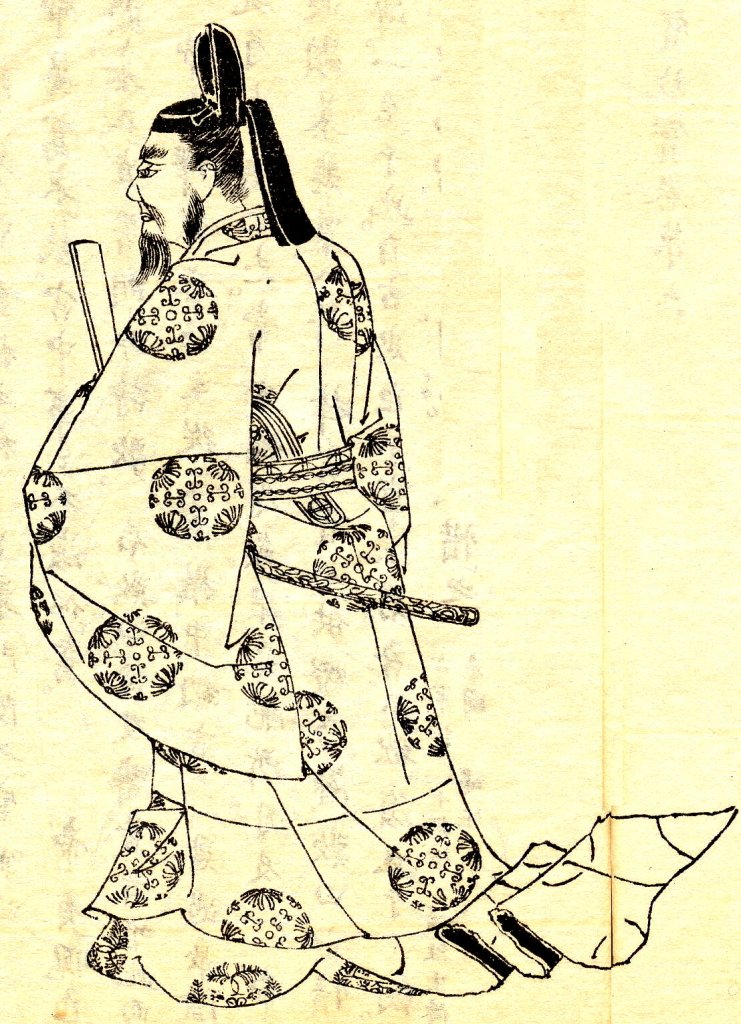

In 645, during the Isshi Incident, the head of the Soga Clan was quite literally cut off. One of the conspirators was Nakatomi no Kamatari, a close friend of Prince Naka no Oe, who would eventually become Emperor Tenji.

Kamatari would use his close relationship with the future Emperor to amass enormous wealth and influence, and shortly before he died, the newly enthroned Tenji bestowed a new family name on him, Fujiwara, and thus, one of the most influential families in Japanese history got its name.

The Fujiwara

The exact origins of the Fujiwara Clan are unclear, but they were originally known as the Nakatomi and claimed descent from the God Ame-no-Koyane, giving them divine origins, although, importantly, of a lesser rank than the Imperial Line.

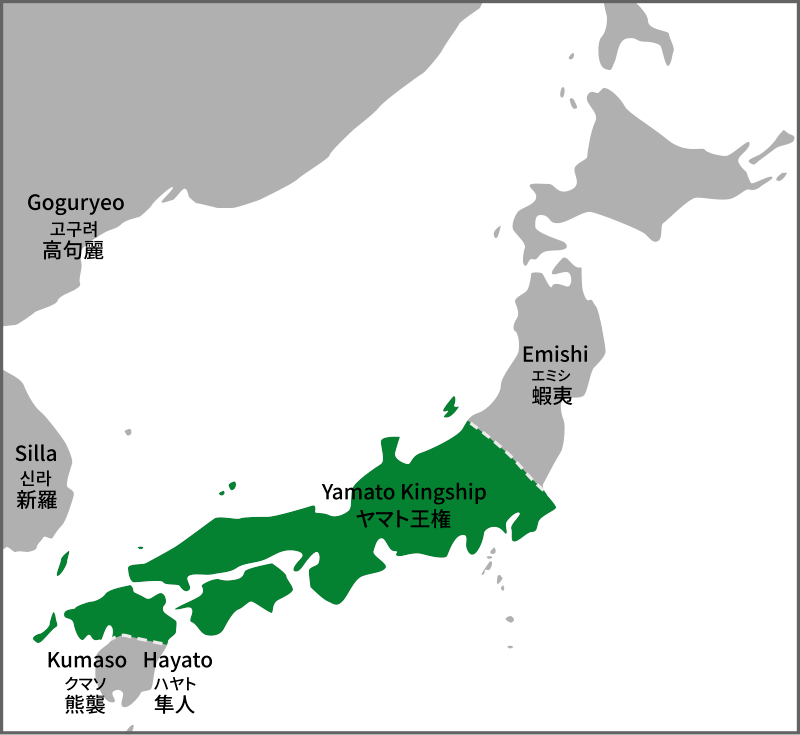

The Nakatomi appear to have been largely responsible for religious ceremonies in the early Yamato Court, but after the Isshi Incident, the renamed Fujiwara gradually adopted the same position that the Soga had before them.

It was the second head of the clan, Fuhito, who really laid the groundwork for Fujiwara dominance, though. Already the scion of a prominent house, he made one daughter the consort of Emperor Monmu and the other the consort of the next Emperor, Shomu. And no, you’re not imagining it; that second daughter would have been Emperor Shomu’s half-aunt. I guess it was ok because both women had different mothers? Maybe?

Consanguinity notwithstanding, Empress Komyo, as she became known later, was significant; not only was she Fujiwara, but she was the first Empress who was not an offspring of the Imperial house.

Fuhito would further expand his family’s dominance by having four sons, who would go on to each head a cadet branch of the Fujiwara. When we speak of the “Fujiwara”, we’re actually going to be talking about these four houses. To keep things simple, I’ll just refer to them as “Fujiwara” unless it’s important to make the distinction, but for reference, the four cadet branches were:

The Kyoke Fujiwara (Capital Fujiwara)

The Shikike Fujiwara (Ceremonial Fujiwara)

The Hokke Fujiwara (Northern Fujiwara)

The Nanke Fujiwara (Southern Fujiwara)

These four houses would work together, and sometimes in opposition to each other, and the Northern and Southern Fujiwara would eventually split into even more Noble Houses that would continue to influence Japanese politics into the modern era, but more on that later.

With their power secured by sometimes incestuous marriage, the Fujiwara moved into position to dominate the throne. By the end of the 10th Century, Fujiwara control of the position of regent had become effectively hereditary, and through other advantageous marriages, Fujiwara influence was felt in the provinces too, with lower-ranking members of the main families taking up positions as administrators and local governors (that will become really important later.)

The Fujiwara wouldn’t have it all their own way. There were several rival families, the most powerful being the Taira and Minamoto, both descended from sons and grandsons of Emperors, and who will get their own post later. There was also the issue of relatively strong Emperors. Political control of the throne depended on controlling the man sitting on it. Some Emperors, like Daigo, who reigned from 897 to 930, proved to be more than a match for the Fujiwara and retained significant control for themselves.

Despite this, Daigo had Fujiwara consorts, and the clan itself would retain its positions at court. When Daigo died in 930, it wasn’t long before things were back to normal, as far as the Fujiwara and their dominance at court was concerned.

In 986, Emperor Kazan was pressured by Fujiwara no Kaneie into abdicating under somewhat dubious circumstances. The story goes that Kaneie convinced Kazan to become a monk alongside his son Fujiwara no Michikane. However, when Kazan entered the temple, Michikane said he would like to visit his family one more time before taking the tonsure. Kazan agreed and became a monk while he waited, but Michikane never came back, which is a ballsy move.

Fujiwara dominance reached its peak in the late 10th and early 11th century under Fujiwara no Michinaga. Michinaga was the third son of Fujiwara no Kaneie, who was succeeded by his son, Michitaka, and then his second son, Michikane, who was regent for only a week before dying; maybe karma for that stunt with former Emperor Kazan?

Michikane’s son, Korechika, had been named heir to the position of regent, but he was opposed by Michinaga and his supporters. Michinaga was already a man of considerable influence and was favoured by the infant Emperor Ichijo’s mother, who happened to be Michinaga’s sister.

Michinaga is said to have played on Korechika’s bad relationship with Emperor Kazan and played a ruse that convinced Korechika that Kazan had been visiting the same mistress as him. The story goes that an enraged Korechika then attempted to shoot Kazan with an arrow, which passed through the former Emperor’s sleeve before the man himself fled.

Korechika was arrested, and though the blame for the attempted shooting fell on servants, he was convicted of having placed a curse on Senshi, Michinaga’s sister and primary supporter. Korechika was exiled to Dazaifu in modern-day Fukuoka, and even though he was pardoned less than a year later and returned to a position in government, his influence was broken, and he was no longer a rival to Michinaga.

Though Michinaga never officially took the title of regent (Kampaku), his position in the government and influence over successive Emperors meant that he effectively ruled the country in all but name. He continued the policy of marrying his daughters to Emperors and the sons of Emperors, and in 1016, he forced Emperor Sanjo (his nephew and son-in-law) to abdicate in favour of his grandson, Go-Ichijo.

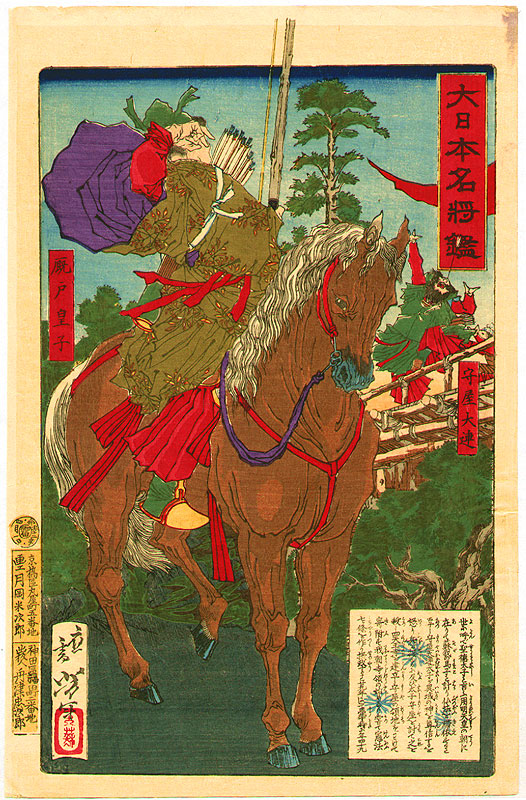

Michinaga also made an alliance with the Minamoto Clan and made use of the brothers Yorinobu and Yorimitsu as his chief enforcers, particularly in eastern Japan. Under the pair, the Minamoto would deal with enemies of the court (which meant enemies of the Fujiwara) and were rewarded with significant lands of their own, which would eventually lead to the creation of a Minamoto power base far from Imperial control, but more on that later.

Michinaga would be succeeded by his son, Yorimichi, in 1019, and though they didn’t know it at the time, the Fujiwara were in decline from then on.

Rise of the Samurai

As we’ve talked about previously, until the late 8th Century, the Imperial court relied on a system of conscription in order to supply its army with manpower. By the dawn of the 9th Century, however, that system had almost entirely broken down and been gradually replaced with private armies under the control of regional landowners.

The loss of military power went hand in hand with a decline in economic resources as well. Under the Taika reforms, the land had all technically belonged to the Emperor and was held in his name in return for a percentage of the harvest as tax.

By the Heian period, however, that system had broken down to. Noble families and powerful temples were able to negotiate tax exemptions for themselves, and local peasants came to avoid tax (and the attached military service) by signing their lands over the local lord in exchange for protection and potentially a better deal tax-wise.

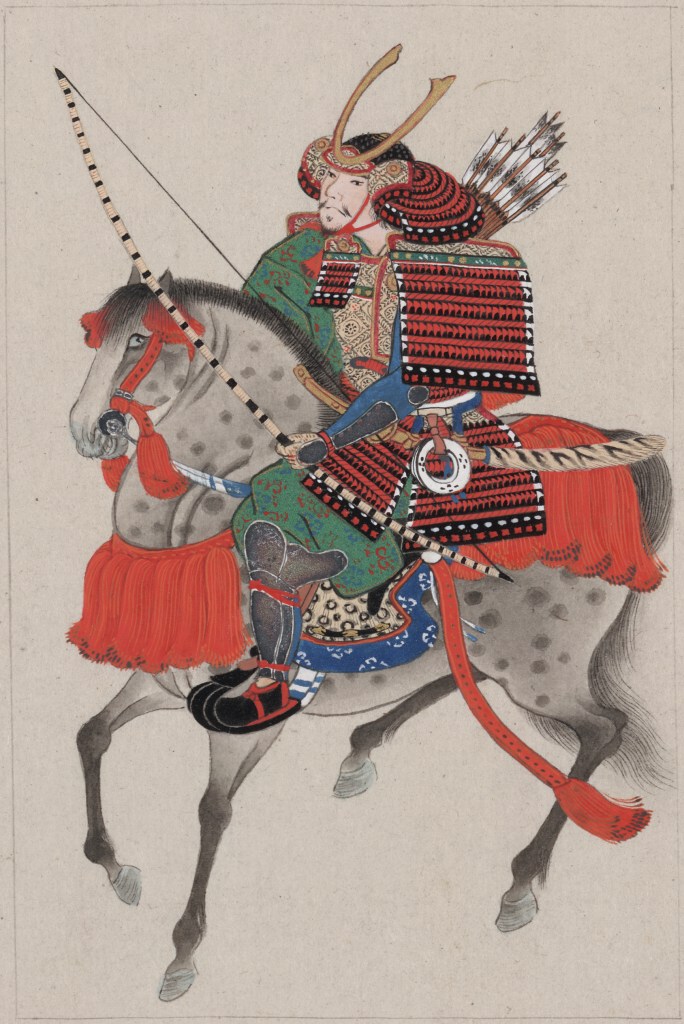

The private armies that sprung up in the wake of this Imperial decline were made up of men who either had land of their own or else were rewarded with it. These men used their resources to purchase horses, training, and weapons (mostly bows at this point), clearly setting themselves apart from the poorly armed masses of peasant conscripts that had come before.

We’ve spoken about how families like the Fujiwara would marry into the Imperial line in order to enhance their own prestige and influence, and these newly minted provincial elites would adopt the same strategy on a more local scale.

The Fujiwara, Minamoto, and Taira families had, by the 11th Century, grown into sprawling clans that would require several dedicated posts to make sense of, but the short version is that most of the members of these clans weren’t the ones playing Game of Thrones in Heian-Kyo. They were dispatched to the provinces by their families to take up positions as governors and other administrators and spread their respective clan’s influence.

These new administrators may not have had the wealth of their capital-based cousins, but they still carried the illustrious names, and marrying into these families would, in turn, bestow aristocratic status. These new nobles, born far from the throne, had little reason to be loyal to it.

Initially, military service was on an ‘as needed’ basis, but by the end of the 10th century, as family ties to local districts deepened, the status of this new warrior class would become hereditary. These warriors were not called Samurai at first; the proper term was Bushi (which literally means Warrior), and their families became Buke or warrior families.

The modern word Bushi is generally applied to all warriors, but it originally applied specifically to men for whom war was their profession, especially those who possessed the expensive armour, weapons, and horse required, meaning the business of making war became limited to a specific class.

By the 10th and 11th Century, the threat of the Emishi had long since passed, and now the powerful regional nobility found themselves with large private armies with no external enemies to fight. So, they asked themselves, what next?

Luckily for them, population growth and diminishing resources gave them the perfect excuse to start fighting amongst themselves. Outbreaks of violence became common, and the Imperial court proved to be incapable of putting a stop to it.

Finding that they could attack their neighbours without any kind of consequences meant that the tenuous loyalty of the regional nobility became no loyalty at all. By the mid-11th Century, even the illusion of Imperial authority was fading, and the Fujiwara, who had seemed unassailable a generation earlier, began to feel the walls closing in.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heian_period

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fujiwara_no_Kamatari

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fujiwara_clan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fujiwara_no_Michinaga

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%97%A4%E5%8E%9F%E5%AC%89%E5%AD%90

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%97%A4%E5%8E%9F%E9%81%93%E9%95%B7#%E5%9B%BD%E5%AE%9D%E3%83%BB%E5%BE%A1%E5%A0%82%E9%96%A2%E7%99%BD%E8%A8%98

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%97%A4%E5%8E%9F%E9%81%93%E9%95%B7

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emperor_Kazan

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BE%8D