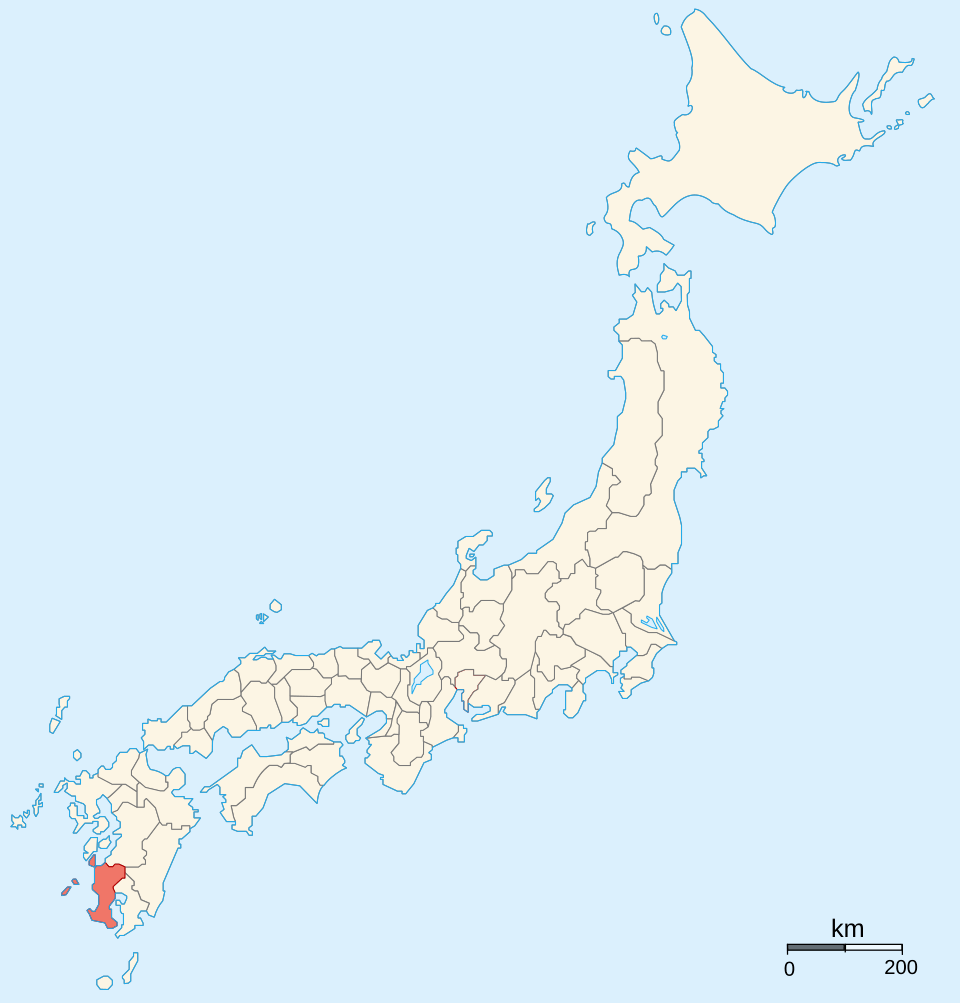

Last time we looked at Shikoku, the so-called ‘four provinces’, well, how about an island of nine provinces? That’s right, Kyushu, the third largest of Japan’s main islands, is so called because in the pre-modern period it was home to nine whole provinces, which means, as names go, it’s not terribly creative, but what can you do?

By TUBS – This vector image includes elements that have been taken or adapted from this file:, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16385933

In ancient times, Kyushu had been the centre of cultural, economic, and social development in Japan, as its close proximity to Korea, and by extension China, made it the logical landing site for innovations as widespread as rice farming and written language. The island would also be the focus of two ultimately unsuccessful Mongol invasions in the 13th Century, and the Shogunate administration there would continue to be important until the decline of central authority in the 15th Century left Kyushu, much like the rest of the realm, effectively independent.

Into this power vacuum stepped several powerful clans, with the most prominent arguably being the Ouchi, Otomo, and Shimazu. Though the Ouchi and Otomo would play important roles of their own in the story of the Sengoku Period, it is the Shimazu that we will be focusing on.

The exact origins of the Shimazu name aren’t entirely clear, but the first figure to take the name was Tadahisa, who was made lord of the Shimazu Manor in southern Kyushu in 1185. Tadahisa himself is something of a mysterious figure, with various conflicting reports of his origins, parentage, and even his name, but what is clear is that the Shimazu were well established in southern Kyushu by the 13th century, and would use it as their base going forward.

Tadahisa’s son, Tadatoki, seems to have been an accomplished military leader, as he was appointed the shugo (military governor) of Satsuma, Osumi, and Hyuga Provinces, all of southern Kyushu in effect. He was also granted numerous prestigious lands and titles around the realm, but it was his Kyushu holdings that would be the most important for his descendants.

The Shimazu’s fortunes would ebb and flow over time, but the distance of their lands from the centre of power in Kyoto meant that they were often able to weather the storms of early Medieval Japan. They were not immune from the ever-present problem of internal conflict, however, and by the time of the Onin War in 1467, the Shimazu were weak, divided, and vulnerable.

It would be Shimazu Tadayoshi (1492-1568) who would begin to turn the fortunes of the clan around. Originally from the Isaku Clan (a branch of the Shimazu), Tadayoshi had a difficult start to life. His father, Yoshihisa, was apparently murdered by a stable hand when Tadayoshi was just two, and his grandfather was killed in battle in 1500. Following this, Tadayoshi’s mother, Lady Baiso, agreed to marry the lord of another branch of the Shimazu, on the condition that Tadayoshi be adopted as heir to both branches. The lord in question was apparently so keen on Lady Baiso that he agreed.

Tadayoshi proved to be an enlightened and capable ruler, taking inspiration from Zen teachings and humanitarian principles. He was a popular leader, as he genuinely cared for the needs of his retainers and the welfare of his territory, but his son, Takahisa, would prove to be greater still. In 1526, following the deaths in quick succession of both his sons, the head of the main branch of the Shimazu Clan, Katsuhisa, turned to Tadayoshi (renowned for his learning and upright conduct) for a solution to the succession issue.

Tadayoshi had Takahisa adopted by the Lord of the Shimazu. In November 1526, Katsuhisa handed over control of the Shimazu Clan to Takahisa and retired to a monastery. Tadayoshi became a monk himself shortly afterwards and would go on to play a significant role in aiding his son in reestablishing Shimazu power in southern Kyushu.

Things are never quite that simple, however, and Takahisa’s accession to the leadership of the Shimazu was opposed by several powerful retainers, some of whom also claimed the right to lead. Katsuhisa himself also seems to have expressed some regret about handing over power, and in June 1527, an army was raised which drove Takahisa out, and had Katsuhisa returned as the shugo.

The fighting would go back and forth for a while after this, despite unsuccessful efforts to arrange a reconciliation in 1529. Katsuhisa proved to be an unpopular lord, however, apparently being more focused on ‘vulgar entertainment’ than the business of ruling. Though this did not automatically translate into support for Takahisa, the division amongst his enemies handed him the initiative.

Starting in 1533, Takahisa would lead a series of counter-attacks which eventually saw him establish control over most of Satsuma Province, and in 1539, the decisive Battle of Murasakihara saw Takahisa drive out his primary rivals, though it wouldn’t be until 1552 that he was finally recognised as the shugo of Satsuma Province by the Shogunate, 26 years after he had first assumed the mantle.

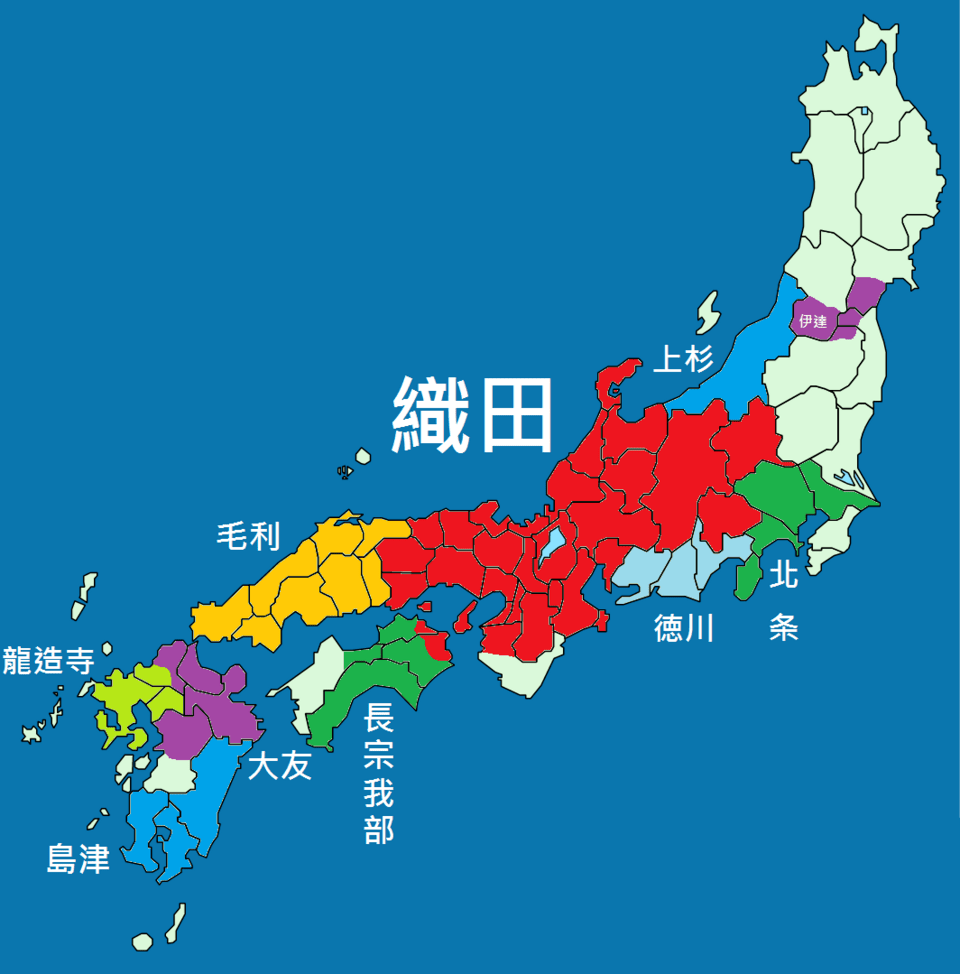

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1691755

Takahisa had long hoped to reestablish Shimazu control of the three provinces held by his ancestors, and he would lead campaigns into neighbouring Osumi province from 1554 to 1556, which would allow him to establish a foothold in the province from which further expansion could be launched.

Though Takahisa would prove to be a successful warrior, he was also known for his outward-looking attitude towards foreigners. The Shimazu had long had trade with Ming China, largely through intermediaries in the Ryukyu Islands (modern Okinawa), and after Portuguese merchants arrived in Japan, Takahisa was one of the first lords to welcome them to his domains, and perhaps one of the first to employ firearms in battle.

He would also go some way to establishing Christianity in Japan, as he welcomed Francis Xavier into his territory in 1549, though this would ultimately prove a short-lived association, due to backlash from conservative elements amongst the Buddhist and Shinto priesthoods.

Takahisa would eventually retire to a monastery in 1556, handing control of the Shimazu over to his son, Yoshihisa, who also inherited his father’s ambitions to regain control of the three provinces of Satsuma, Osumi, and Hyuga. Yoshihisa had actually joined his father’s campaign in Osumi, making his ‘debut’ in 1554, and after inheriting the leadership from his father, he would continue the campaigns to fully pacify Satsuma and expand Shimazu holdings into the neighbouring provinces.

Satsuma would come under his complete control in 1570. In 1572, a rival clan from Hyuga Province would invade Shimazu territory, only to be defeated in short order at the Battle of Kizakihara, with the Shimazu forces being led by Yoshihisa’s highly capable younger brother, Yoshihiro. It is said that the Shimazu, despite being outnumbered 10 to 1, launched an aggressive attack against the enemy, which saw several key leaders killed and over 500 enemy deaths (counted in heads taken after the battle).

This victory allowed Yoshihisa to focus on Osumi Province, which he was able to fully conquer by the end of 1573. Then in 1576, he captured the strategically important Takahara Castle, held by the powerful Ito Clan of Hyuga. The fall of Takahara led to a domino effect in which the remaining 48 castles of the Ito Clan were either conquered or defected to the Shimazu. Not long after, the head of the Ito Clan, Yoshisuke, fled Hyuga, and the long-dreamt-of reunification of the three provinces was achieved.

Almost as soon as the dust had settled, however, the powerful Otomo Clan, who controlled several provinces in North-Eastern Kyushu, invaded, nominally in support of the exiled Yoshisuke, but more likely in an opportunistic attempt to expand their own territory. A huge army of some 43,000 men crossed into Hyuga Province in October 1578 and laid siege to Takashiro Castle. The Shimazu under Yoshihisa could muster only 20,000 men in response, but they took advantage of poor coordination amongst the Otomo, dealing with the invaders piecemeal.

The campaign culminated in the Battle of Mimikawa (which was actually fought nearly 20 miles from the eponymous river), in which Yoshihisa employed a series of feigned retreats, breaking the Otomo Army (which still enjoyed a numerical advantage) down, and eventually winning a victory that was so comprehensive the Otomo effectively ceased to be serious rivals.

The war wouldn’t end at Mimikawa, however, and in 1580, Oda Nobunaga began negotiations between the Otomo and Shimazu, hoping to bring an end to the war, since he wanted the Otomo to join his upcoming campaign against the Mori. The negotiations were apparently successful, as Yoshihisa even went so far as to recognise Nobunaga as his ‘lord’, and planned to join the attack on the Mori as well.

By Alvin Lee – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39198356

As we already know, Nobunaga’s death at the Honnoji incident in June 1582 put an end to those plans, but the weakened state of the Otomo and the fact that the peace deal no longer applied meant that the Shimazu were able to defeat or force the defection of several former Otomo retainers, increasing their own power and control over southern Kyushu.

The campaign to unify the entire island would go on, but we’ll look at that next time.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B3%B6%E6%B4%A5%E7%BE%A9%E4%B9%85

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%80%B3%E5%B7%9D%E3%81%AE%E6%88%A6%E3%81%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A4%A7%E5%8F%8B%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B3%B6%E6%B4%A5%E7%BE%A9%E5%BC%98

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B3%B6%E6%B4%A5%E8%B2%B4%E4%B9%85

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B3%B6%E6%B4%A5%E5%BF%A0%E8%89%AF

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%A2%85%E7%AA%93%E5%A4%AB%E4%BA%BA

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%96%A9%E6%91%A9%E5%9B%BD

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shimazu_Takahisa

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B3%B6%E6%B4%A5%E5%BF%A0%E4%B9%85

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%B3%B6%E6%B4%A5%E6%B0%8F

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_daimy%C5%8Ds_from_the_Sengoku_period