Last time, we talked about how the Heian Period began in 794 when Emperor Kanmu moved the capital to Heian-Kyo, where it would remain for the next thousand years.

We also looked at how the Heian court abdicated its military power to the regional nobility, who, facing a long-term war against the Emishi tribes of Northern and Eastern Japan, no longer put their faith in the large, pretty ineffective conscript armies of the Imperial court, instead establishing private armies of their own, adopting the horse archery tactics of their enemies. Although the days in which the warrior class would dominate the Emperor are still far in the future at this point, the origins of the Samurai can be found here.

The problems didn’t end with the army, either. Although conscription had been brought in with the Taika reforms of the mid to late 7th century, by the end of the 8th century, the system had largely broken down. This was because it relied on another of the reform’s offspring, control of land.

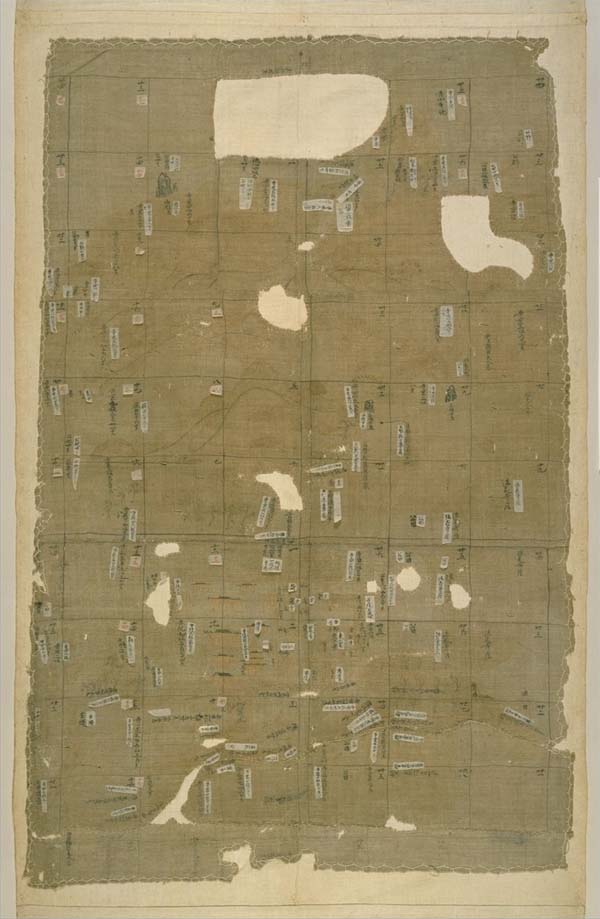

Like pretty much everything else in the Taika Reforms, land reform was modelled on the Chinese system. Officially, land was under the control of the state, and every free man was entitled to a certain amount, which would then be taxed. There was no national currency at the time, so taxation was usually a percentage of the harvest.

Now, in theory, this meant that everyone had land to support themselves and a regular tax income for the court. However, the system quickly ran into problems. Firstly, unlike the Chinese system, people in Japan couldn’t claim wasteland, even if they farmed it. Additionally, land couldn’t be inherited by someone’s heir. This had the double blow of meaning that there was little reason to expand or enhance holdings, which would have been fine if it had not been for population growth.

It’s ironic, looking at Japan in 2025, that population growth turned out to be a problem, but there you are.

As the population grew, so did the demand for food (obviously). The land system couldn’t keep up with demand, so the government eventually changed the law to allow anyone to claim wasteland as long as they farmed it.

Now, you’d think that’d be problem solved, more land means more food. But no, and the reason is because of taxation.

Now, as we said, taxation was based on percentages of the harvest, but there were a lot of exemptions. Land owned by temples and powerful noble families was exempt from taxation, which meant a concentration of wealth and resources in the hands of relatively few.

This meant that when the government relaxed controls on claiming land, the ones who benefited weren’t the farmers but those with the manpower to claim land faster than anyone else. Consequently, the rich got richer, but none of that wealth made it into the Imperial coffers because, as we said, it was all tax-exempt.

So, you now had a situation where a small portion of the population owned most of the wealth, and this further eroded the government’s ability to function. They’d already lost control of the military, and now they’d lost control of the food supply. That’s 2-0 to the nobility, in case any of you have been keeping score.

Now, you might ask, if land couldn’t be inherited, then surely the government would regain control of it on the landowner’s death, right? Sorry, nope. Not only did the government change the rules on land reclamation, but also on inheritance. This meant that, after the Temples and Nobles had gobbled up all the good land, they were then able to keep it within their family, creating generational wealth and power.

Wealth means Power.

So, what about the peasants who owned their land but weren’t part of the nobility? They’d have a reason to want things to stay as they are and support the status quo, right? Well, no, not exactly.

As we’ve mentioned, the estates (Shoen in Japanese) of the nobility and temples were tax-exempt. The peasants who owned their own land still had to pay a percentage of each harvest to the Emperor since he technically owned their land.

Your average Heian-era farmer had probably never even been to Heian-kyo, let alone actually seen the Emperor, so when the tax collectors came, they were the very embodiment of the faceless bureaucracy.

Now, this might not seem so strange to us, after all, we all pay tax, and how many of us ever meet our head of state? But the world was smaller back then; the rise of the local aristocracy, many of whom had positions of local authority, meant that, as far as the peasantry were concerned, the government wasn’t the Emperor, who might have been hundreds of miles away, but the local magistrate, who was often also the wealthiest landowner.

This breakdown in authority benefited the nobility politically in the same way as it had economically and militarily, but there was another twist to come. With local political and military control already falling into their hands, the local aristocracy was able to exert considerable pressure on the nominally free peasants around them.

The exact process isn’t well documented, but we do know that the peasants who controlled their own fields would often sign the ownership of that field over to a powerful local magnate, whether than be a Temple or a noble. In effect, this granted the field tax-exempt status, and instead of tax, the peasant would then pay “rent” to the new owner for the right to keep working the field.

There are other examples of this happening in a more direct way, with local nobles demanding tribute from free peasants and then confiscating their fields if they couldn’t (or wouldn’t) pay.

Now, as we’ve said previously, taxation was in the form of harvest or conscription, either into the army or as labour. This didn’t really change that much; harvests were still taxed, and peasants, instead of doing service to the Emperor, were now obliged to serve their local lord.

It should be pointed out that, under the original system, peasants weren’t tied to the land. They held it in their own name, technically as direct “vassals” of the Emperor. (They weren’t legally vassals in the Feudal sense, mind you.)

As the Heian period went on, and more and more land was taken by the nobility, the status of peasants also changed. Instead of holding their own land, they were often bound to those same fields, but now in the service of someone else. At first, it was economic necessity; as much as the fields may have been ‘free’, the peasantry still needed to eat, and if that meant working for the lord, then so be it.

Later, though, economic necessity gave way to legal reality. Everyone was technically subject to the Emperor, but the situation on the ground increasingly disadvantaged the peasants. What had been an economic arrangement became effectively a feudal one as landowners began to deal with local legal matters themselves.

A peasant (Shomin in Japanese) could now be kicked out of the Shoen (estate) if the Lord didn’t like him, and matters of justice, which had formerly been the reserve of Imperial officials, now became the domain of local lords as well. Where a peasant might have once had the right to petition the Emperor directly, now, the final arbiter of justice was his Lord, and you will probably not be surprised to find out that these Lords often interpreted the ‘law’ in ways that most benefited them.

Imperial Irrelevance

So what did the Emperor do about this?

The answer is simply, nothing really. It’s not that they didn’t know it was happening, but there was precious little they could do. There was no effective means to impose Imperial will on the increasingly independent nobility, and they knew it.

The Imperial Army, formerly conscripted from the fields, no longer existed, and, lacking any formal currency, the economy had begun to be based almost entirely on rice, which had also long since slipped from Imperial hands.

There were legal attempts to turn things around. In 1040, a law was passed that officially banned any new lands from being granted tax-exempt status, but it was too little, too late.

Not that the Imperial Court minded all that much; they kept themselves busy with books, paintings, and some of the most ridiculous eyebrows you’ve ever seen, but we’ll cover that next time.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heian_period

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sh%C5%8Den

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ritsury%C5%8D