Due to the sheer volume of information I want to share about the Heian Period, these next few posts are going to be a mix of different things; today, we’re going to talk about some of the military aspects of the early Heian Period, which will be important for later, so pay attention.

Last time, we looked at the Yamato Period, where a recognisable Imperial system emerged from myriad proto-kingdoms and tribal states. By the late 8th century, following a period of extensive reform, power had been (theoretically) centralised in the hands of the reigning Emperor but was, in reality, in the hands of various noble factions who had no qualms about committing acts of violence in the defence of their interests.

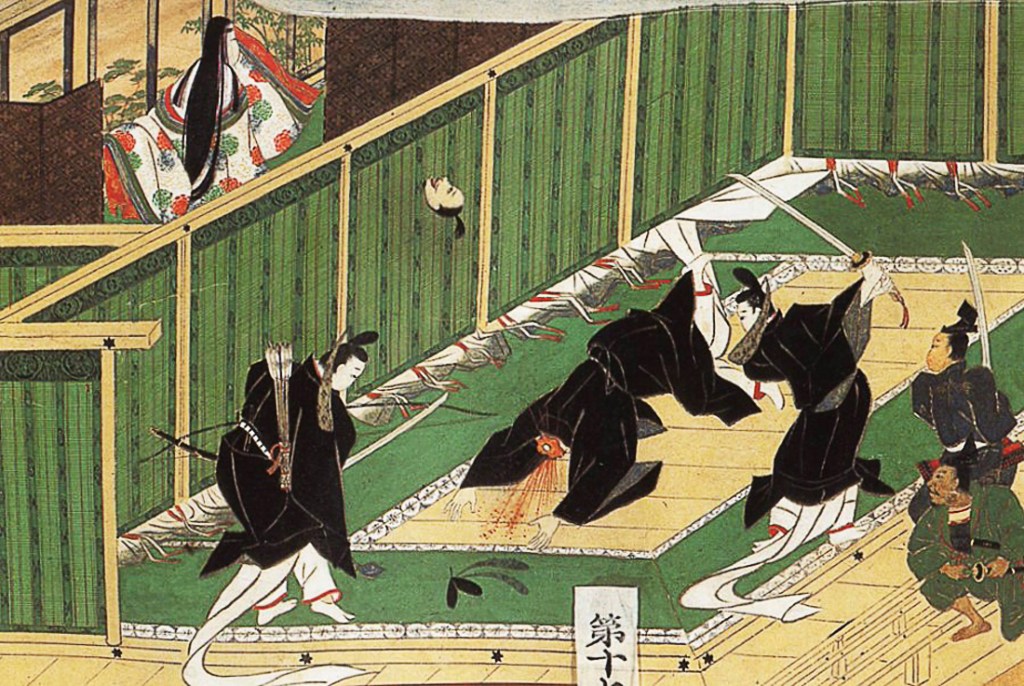

After the Isshi Incident in 645, which saw the leadership of the formerly dominant Soga Clan eliminated, the Imperial Throne was able to reassert its independence. One of the co-conspirators in the incident was Nakatomi no Kamatari, who was one of the initiators of the Taika Reforms we looked at last time. He was also a close supporter of Prince Naka no Oe, who had also taken a leading role in the Isshi Incident.

Now, this isn’t some random tangent; when Prince Naka no Oe became Emperor Tenji in 668, Nakatomi rose still higher. On the latter’s deathbed in 669, the Emperor bestowed a new family name on him. From then on, Nakatomi no Kamatari and his descendants would be known as the Fujiwara.

New Capital, Old Problems

The Heian Period is named after and started in the new Imperial Capital, Heian-Kyo, which means City of Peace (or tranquillity, if you’re feeling poetic). It was the 50th Emperor, Kanmu, who moved the capital there in 794, and it remained the seat of the Emperors until 1868. It is better known today as Kyoto.

Although 794 officially marks the beginning of the Heian Period, the seeds for what would come had already been sown in the years prior. Since the arrival of Buddhism in Japan and the victory of the pro-Buddhist factions that we looked at last time, the Buddhist Clergy had become politically powerful, leading to problems between them, the nobility, and the Emperor.

In 784, Kanmu initially moved the capital from Heijo-kyo (near modern Nara) to Nagaoka-kyo (confusingly, located mostly in modern Muko, Kyoto Prefecture, not the nearby city of Nagaokakyo).

The move was, at least in part, motivated by a desire to separate the Imperial Capital from the influence of powerful Buddhist temples that had emerged near Nara. However, the move would prove unsuccessful. Political intrigue followed the court, and less than a year after the move was formalised, the primary architect, Fujiwara no Tanetsugu, was assassinated by a rival faction. (There’s that Fujiwara name again.)

In the aftermath of the killing, numerous court officials and even members of the Imperial Family were arrested. Some were executed, whilst others were exiled, including the Emperor’s brother, Prince Sawara. Unfortunately, Sawara died en route, and in the years that followed, Nagaoka-kyo suffered several disasters, floods, famines, fires, and the deaths of many important people.

Now, these days, we might put that down to bad luck or to deliberate attempts to undermine the Emperor, but the people back then were a superstitious lot, and when, in 792, the disasters were blamed on Prince Sawara’s vengeful spirit (Onryo in Japanese) the decision was taken to move the capital once again.

The Emperor would learn, however, that freeing himself from the influence of powerful priests wasn’t going to be the great liberation he had hoped for, but more on that later.

The Imperial Army

We’ve not looked at military stuff very much so far, mostly because there is going to be a lot of that later, but a quick look at the Imperial Army and the war with the Emishi is important for what’s coming.

Decades before the move to Heian-kyo, the Taika Reforms had led to a restructuring of the young nation’s military. Prior to the reforms, military power was in the hands of regional strongmen (politely called ‘nobility’), whose power was usually based around fortified settlements and the surrounding lands.

With the Taika Reforms, however, the Imperial Government, inspired by Tang Dynasty China, instituted a system of conscription. The idea was that military power would pass from the hands of the nobles into the hands of the Emperor.

It didn’t really work out that way, though. Firstly, the burden, as it so often does, fell on the poor, as those with sufficient resources could buy or trade their way out of service (corruption may also have been an issue). Since the poor are generally tied to the land, this led to people fleeing their home regions to avoid the army, with the knock-on effect being fewer people in the fields.

Another issue was that conscription, by its nature, relies on men who don’t actually want to be there. There are examples throughout history of military service being a way out of economic hardship, but that doesn’t seem to have been so here. Men assigned to the frontier were expected to pay for their own equipment and provisions, meaning that the little money they might earn in the army was quickly spent simply being in the army.

It is perhaps unsurprising then that the Imperial Army was poorly equipped and badly motivated. This wouldn’t have been much of a problem had their role simply been to keep the peace, but the early Emperors were expansionists, so their poorly motivated army was kept busy.

The Emishi

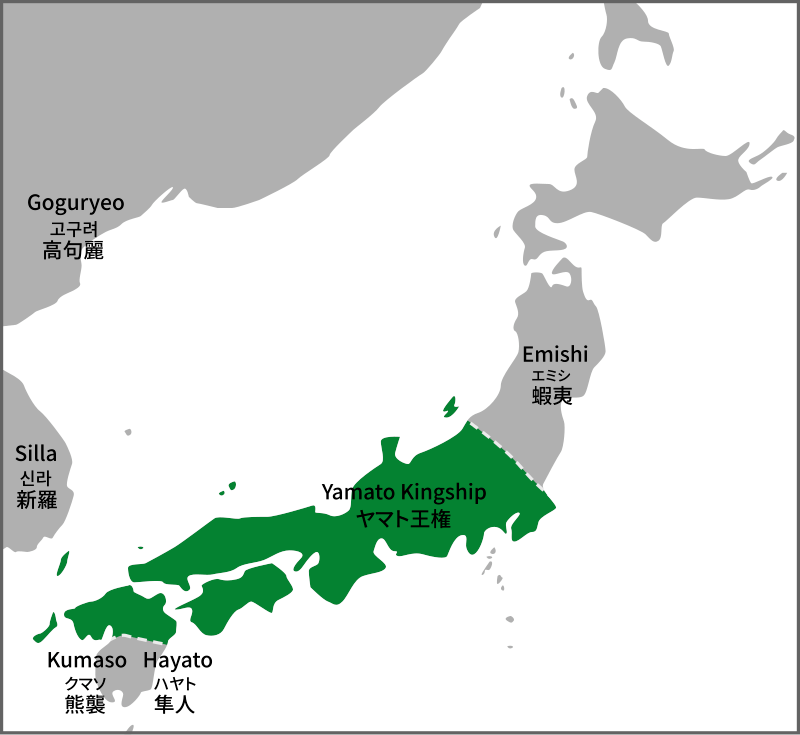

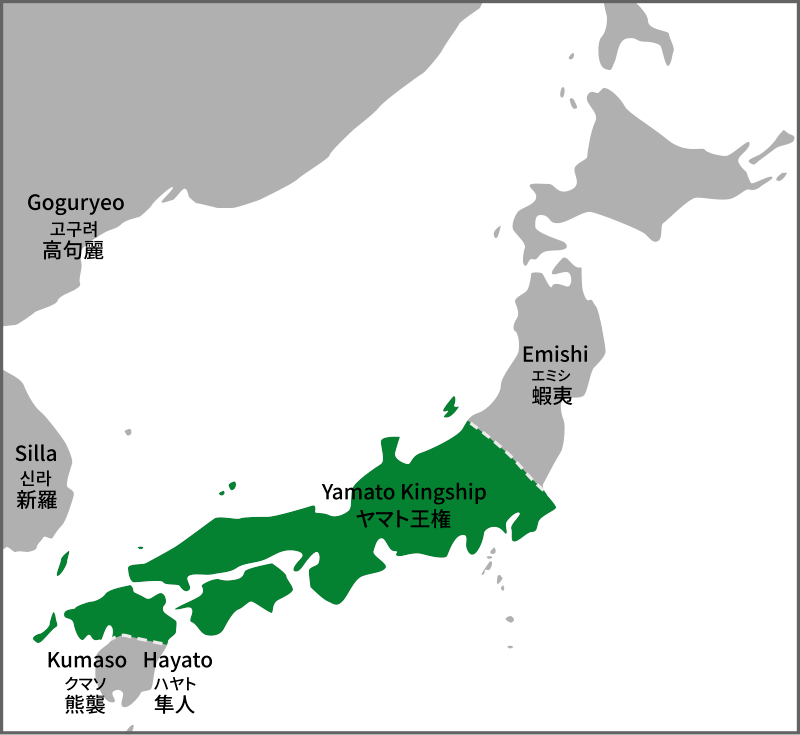

Who were the Emishi? Well, as is often the case, there isn’t a definitive answer. The earliest records we have for them are Chinese and date to the 5th Century, where there is mention of “55 Kingdoms” of “Hairy People of the East”. Exactly who these people were isn’t clear, but they are distinct from the “Japanese” kingdoms that are also recorded.

It is generally believed that the Emishi were linked to the Jomon, who inhabited Japan before the Yayoi (who became the Yamato and so on). It is also accepted that the Ainu are also connected to the Emishi, but the exact relationship is unclear and may never be known for certain.

What is certain is that the Emishi proved to be an opponent that the Yamato initially struggled to overcome. Whilst the independent peoples in Kyushu were subjugated fairly early on (either through force or diplomacy), the Emishi remained largely independent into the 8th Century.

By Samhanin – Own work, source: Yamato ja.png, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=121731575

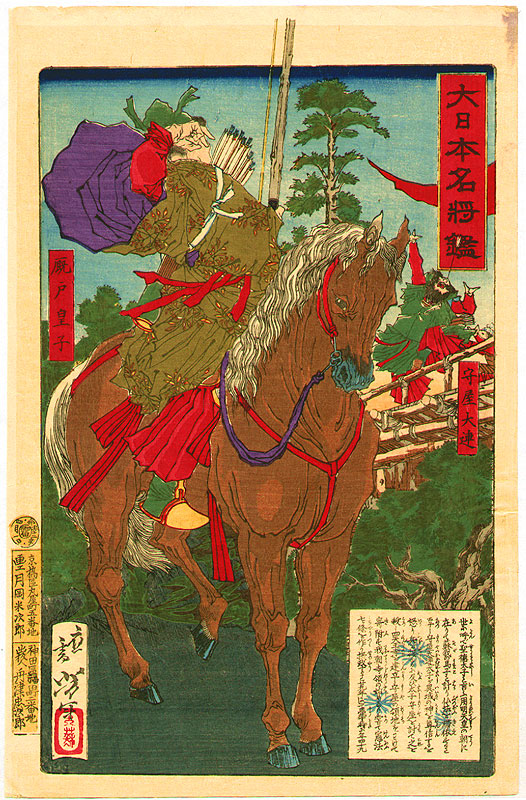

The Emishi would prove to be resistant to traditional military strategy. They relied on horse archery, using speed and guerilla tactics to defy the Yamato. For most of the 7th and 8th centuries, the Yamato would advance slowly, building forts as they went and dealing with individual Emishi tribes, some of whom would agree to enter Imperial service.

In 774, the so-called Thirty-eight Years War began when the Emishi launched a series of attacks on Yamato forts in Northern Japan. The Emishi would prove to be successful at first; imperial armies were gathered quickly and sent against the Emishi, only for the Emishi themselves to melt away and reappear somewhere else. Forts, Towns, and Villages were burned, and through the 780’s, the situation spiralled out of control.

The war would go on for 38 years (hence the name), and it would be a combination of diplomacy and a change in strategy that eventually led to Yamato’s victory and dominance of the North.

Militarily, the Yamato adopted the mounted archery tactics of their enemy. This couldn’t be done with conscripts from the back end of nowhere, but the local nobility, who had been dealing with the Emishi for years already, were quicker to catch on, and these “Emishi-busting” armies were often smaller, faster moving, and, most importantly, loyal to their local communities over the Imperial Court.

By the 790s, the strain of constant campaigns against the Emishi had led to a breakdown in the system of conscription. The people didn’t want to be sent to fight, and the Imperial Court couldn’t afford to send them, meaning that military strength now rested entirely in the hands of local nobility, but I’m sure that’ll be fine.

On the diplomatic front, the Yamato reached out to the tribes who might agree to switch sides, and unsurprisingly, many would. The leaders of these tribes were quickly integrated into local nobility, and it is said that several later Clans could trace their ancestry to Emishi progenitors.

By the dawn of the 9th century, the Emishi were largely dealt with. Those who had submitted were subsumed by Yamato culture, and over the years, they would become indistinguishable from other Japanese. Those who refused to submit, however, were either destroyed or driven north to Hokkaido, where they would play no further part in the Heian story.

Now what?

So, the Emishi are beaten, the Empire has won, and all is right in the world. I’m sure that the fact that military power has fallen completely out of imperial hands into the lap of a regionally powerful nobility that controls not only the military but the economic levers of power after the collapse of central taxation led to a system that relies almost entirely on agricultural output to support itself won’t lead to any problems, will it?

There’s that foreshadowing again.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heian_period

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heian-ky%C5%8D

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emperor_Kanmu

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nagaoka-ky%C5%8D

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emishi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fujiwara_no_Kamatari

https://fee.org/articles/were-japans-taika-reforms-a-good-idea/