By the end of the 14th Century, the Ashikaga Shogunate might have been forgiven for thinking it was in a strong position. Under Shogun Yoshimitsu, Kyushu had been pacified, the power of the mighty clans close to the capital had been curtailed, and in 1392, a reconciliation had been arranged between the Northern and Southern Imperial Courts, bringing an end to the Nanbokucho Period.

In 1395, Yoshimitsu officially retired from the Shogunate to become a monk, and although he retained actual power, the succession of his son, Yoshimochi, was secure. Then, in 1399, the Ouchi Clan rose in rebellion in Kyushu, and in crushing them, the Ashikaga Shoguns no longer faced any serious opposition in the South or West of the realm.

Around this time, Yoshimitsu sought recognition as “King of Japan” from the Ming Emperor of China, as he had long been an admirer of Chinese culture and politics. Initially, the Chinese refused to recognise him, because, as Shogun, Yoshimitsu was (technically) a servant of the Emperor, whom the Chinese were more inclined to recognise as King.

When Yoshimitsu retired as Shogun, however, he retained all the power of his position, but was now free of his position as a subordinate of the Emperor. This, combined with a promise to suppress the often serious problem of piracy (wako) in the waters around Korea, persuaded the Chinese to formally recognise Yoshimitsu as “King” and restart trade between Japan and China, in exchange for regular Japanese tribute as ‘subordinates’ to the Ming.

This trade was not as we might imagine it, where merchants buy and sell according to the laws of supply and demand. Instead, as the Chinese viewed themselves as the centre of the world, they viewed trade as being based on tribute to their Emperor, with gifts being bestowed in return.

This worldview, combined with the Chinese desire to show off their wealth, meant that Japanese trade missions would often end up with such quantities of goods that they were able to secure enormous profits. One example comes from the merchant, Kusuba Sainin, who claimed that thread purchased for 250 mon in China could easily be sold for 5000 mon back in Japan.

(The mon is a Japanese unit of currency that wasn’t very well formalised before the Edo Period, making modern purchasing power hard to figure out, but the fact that this represents around 2000% profit gives you an idea of how lucrative this trade could be.)

These ships were only sent relatively infrequently; in fact, between 1404 and 1547, only 17 trade missions (made up of 84 ships in total) were sent, but the influx of Chinese material and cultural goods, and the Shogunate’s 10% levy on all goods arriving in Japan, meant that it was a major source of revenue and prestige.

The trade was politically unpopular, however. The Chinese required tribute and acknowledgement of China’s supreme position in the world. Though Yoshimitsu likely viewed this as a diplomatic nicety rather than an actual submission, it didn’t sit right with the prideful Samurai or the Imperial Court, who held that their Emperor was a literal son of heaven, whereas the Chinese Emperor held a mandate that could be lost.

While Yoshimitsu was alive and politically active, these concerns were largely kept private, but the discontent remained, and Yoshimitsu, it may surprise you to learn, wasn’t going to live forever.

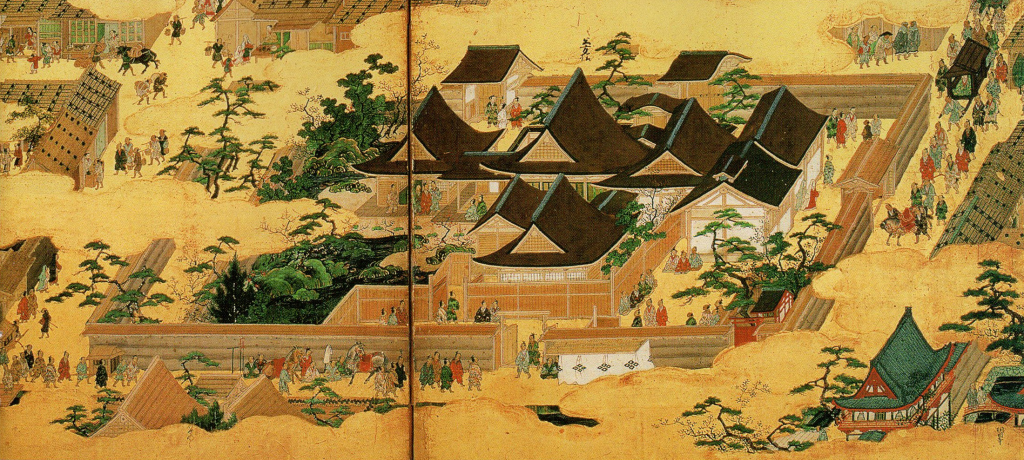

While he lived, however, Yoshimitsu invested this newfound wealth and power in what became known as Kitayama Culture. A unique blend of Imperial, Samurai, and Chinese aesthetics, it gave birth to many famous aspects of Japanese culture that are still recognisable, such as Noh Theatre and even Origami (which began as a much more formalised system than what we may be used to today).

Like many before and after him, Yoshimitsu also invested heavily in architecture, aiming to promote the glory and prestige of his family through buildings that were more spectacular than any that came before. Most famously, the Golden Pavilion Temple, Kinkaku-ji, a landmark so famous that the actual name for the temple, the pavilion, is in (Rokuon-ji), is often forgotten.

By Jaycangel – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=33554210

As we discussed last time, Yoshimitsu had an unusually close relationship with the Imperial Court, taking up several positions in the Imperial Government, and running things in such a way that it often became unclear exactly when Imperial orders weren’t simply Shogunate ones.

This came to something of a logical conclusion in 1404 when Yoshimitsu began lobbying for the position of Retired Emperor. You may recall that, in the days before the Shoguns, Emperors would retire to become insei, or Cloistered Emperors, retaining all the actual power, whilst no longer being constrained by the often burdensome nature of an Emperor’s religious responsibilities.

In the midst of this politicking, in April 1408, Yoshimitsu became ill, dying at the age of 51 in May of the same year. A few days after his passing, the Imperial Court offered to bestow the title of Retired Emperor on him posthumously; however, the new Shogun, Yoshimochi, declined. It has been speculated that this was agreed to previously, as a way to definitely end the Shogunate’s pretensions to the title.

Either way, Yoshimitsu was dead, and things began to unravel quite quickly. Though Yoshimochi had been named Shogun in 1394, when his father had ‘retired’, his actual accession to the title didn’t go unchallenged. Some suggested that Yoshimitsu had actually preferred his younger son for the role, but had died before updating his will.

Because of this, the Shogun’s Deputy (kanrei), Shiba Yoshimasa (of the once powerful, and now resurgent Shiba Clan), pushed to have Yoshimochi recognised as Shogun, and in the short term, a crisis was avoided.

Shiba Yoshimasa had been a powerful figure in the Shogunate for decades, and he had a huge influence over the new Shogun. However, by the time Yoshimochi actually gained power, Yoshimasa was an old man, and in August 1409, he handed the position of Kanrei over to his grandson. The fact that he was a boy of 11 was apparently not a problem, given that Yoshimasa intended to keep real power anyway.

Whether or not he meant to groom his grandson for the role is unclear, because less than a year later, Yoshimasa was dead and the power of the Shiba Clan at the centre of government was at an end.

Unfortunately for the Ashikaga, Yoshimochi turned out not to be his father’s son. No longer under Yoshimasa’s influence, he ended the Chinese trade in 1411 (it would be reinstated later), and in 1415, he faced a serious uprising from loyalists of the former Southern Court, showing that that particular problem had not been resolved.

More seriously, in 1416, a major rebellion broke out in the Kanto Region, when the locally powerful Uesugi Clan rose up against the Kamakura Kubo, the semi-autonomous military governor in the region.

Now, this is a bit complex, so pay attention. The Kamakura Kubo had, since the formation of the Ashikaga Shogunate, been in the hands of a branch of the Ashikaga Family, descended from one of the sons of the first Ashikaga Shogun, Takauji. Therefore, as with a lot of Japanese history it was possible to have Ashikaga on both sides of any conflict, going forwards I’ll make sure to be clear which branch of the family I’m talking about, but it’s a bit of headache.

Confused genealogy aside, the Kubo was, much like their cousins in Kyoto, surrounded by Samurai Clans who were often stronger than the local government. In the Kanto, the most powerful family was the aforementioned Uesugi, and they’d been a real thorn in the side of the Kamakura Ashikaga from the start.

The Uesugi had often held the title of Kanto Kanrei, which is basically the Shogun’s Deputy in the Kanto Region, in which Kamakura lies. Unsurprisingly, the Kamakura Ashikaga and the Uesugi spent most of their time butting heads, and in 1415, a particularly serious disagreement led to the Uesugi being stripped of the kanrei position.

You can probably guess what happened next. The Uesugi refused to accept that, and one thing led to another until in late 1416, they rose in rebellion, taking Kamakura in October. Confused reports reached Kyoto later in the month, some of which suggested that the Kamakura Kubo, Mochiuji, was already dead.

When it became clear that he was, in fact, alive, the Shogun dispatched an army made up of loyal clans to the Kanto to put the rebellion down. This they did, and the Uesugi forces were decisively defeated at the Battle of Seyahara in January 1417, after which their power was severely curtailed.

In the aftermath, Shogun Yoshimochi accused his brother, Yoshitsugu (who had been that potential rival to the throne we mentioned earlier), of being complicit in, or even behind the rebellion. Yoshitsugu pleaded his innocence (as you do), but, fearing for his life, fled the capital and became a monk.

That didn’t save him, and in 1418, he either committed suicide or was murdered on his brother’s orders. The man accused of his assassination was later denounced for apparently having an affair with one of the Shogun’s concubines and killed himself, which is just one of those salacious side stories that make studying history such a joy.

The seeds of more trouble in the Kanto were sown when Mochiuji pursued a policy of revenge against those who had rebelled, despite the Shogun’s official desire for reconciliation. Direct conflict would be a while in coming, but the increasingly defiant Kanto Lords could not be ignored forever.

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E5%97%A3

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8C%97%E5%B1%B1%E6%96%87%E5%8C%96

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%97%A5%E6%98%8E%E8%B2%BF%E6%98%93

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%A5%A0%E8%91%89%E8%A5%BF%E5%BF%8D

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kinkaku-ji

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E6%8C%81

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%8A%E6%9D%89%E7%A6%85%E7%A7%80%E3%81%AE%E4%B9%B1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E6%8C%81%E6%B0%8F#%E5%AE%98%E6%AD%B4

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%96%AF%E6%B3%A2%E7%BE%A9%E5%B0%86#%E7%AE%A1%E9%A0%98%E5%B0%B1%E4%BB%BB%E3%81%A8%E5%A4%B1%E8%84%9A

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%81%A3%E6%98%8E%E8%88%B9