The Wa dwell on mountainous islands southeast of Han [Korea] in the middle of the ocean, forming more than one hundred communities. From the time of the overthrow of Chaoxian [northern Korea] by Emperor Wu (BC 140–87), nearly thirty of these communities have held intercourse with the Han [dynasty] court by envoys or scribes. Each community has its king, whose office is hereditary. The King of Great Wa [Yamato] resides in the country of Yamadai.

Goodrich, Carrington C, ed. (1951). Japan in the Chinese Dynastic Histories: Later Han Through Ming Dynasties. Translated by Tsunoda, Ryusaku. South Pasadena: PD and Ione Perkins. Taken from Wikipedia.

At the back end of the Yayoi Period (c. 300 BC to 300 AD), the first petty kingdoms began to emerge. These communities initially started out based on agriculture and shared culture (cemeteries and other ritual sites, for example), but by the late Yayoi period, we begin to see evidence of defences being constructed.

By Flamebroil at the English-language Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4443146

Now, it may seem obvious, but you don’t need defences unless you think someone is going to attack you, and you can’t typically organise coordinated attacks against defended places without someone calling the shots.

So now, the age-old question, which came first, the Kings or the Wars? Humans have never needed much of an excuse to start killing each other, and evidence for violent deaths reaches back to the Jomon period.

Violence, however, is not the same thing as war. The marshalling of resources, and the building of defences require organisation, and organisation in those days meant monarchy.

These days, we tend to associate Monarchs with pomp and ceremony but usually (at least in Europe) very little actual power. In the ancient world, however, you didn’t get to be King or Queen without power, and that power usually came from one of two places.

Either you were the biggest and the strongest, and you simply killed anyone who got in your way, or you relied on more spiritual power, either magic or religion.

Now, the late Yayoi people didn’t have writing, so we don’t know very much about how they saw themselves, but the Chinese sources suggest that monarchy and magic were tightly linked.

When speaking of Himiko, the legendary Queen of Yamatai, the sources speak of a Queen who:

occupied herself with magic and sorcery, bewitching the people. Though mature in age, she remained unmarried. She had a younger brother who assisted her in ruling the country. After she became the ruler, there were few who saw her. She had one thousand women as attendants, but only one man. He served her food and drink and acted as a medium of communication. She resided in a palace surrounded by towers and stockades, with armed guards in a state of constant vigilance.

Goodrich, Carrington C, ed. (1951). Japan in the Chinese Dynastic Histories: Later Han Through Ming Dynasties. Translated by Tsunoda, Ryusaku. South Pasadena: PD and Ione Perkins. Taken from Wikipedia.

If we ignore the trope of any woman in power obviously being a witch, this source tells us that Himiko was viewed as being a user of magic who remained aloof from her people, surrounded by towers, stockades, and armed guards. It is often difficult to separate fact from fiction when it comes to such ancient sources, but the mention of elaborate defences tallies with the archaeological evidence.

Even if Himiko herself is mythical, the fact that Late Yayoi settlements were being defended by armed guards seems to support the idea that Japan was becoming a more centralised but also more violent place.

Monumental Tombs

Another example of centralisation is the emergence of monumental tombs called Kofun. Like the Pyramids of Egypt, Kofun started out as burial chambers of important, presumably royal figures, and they represent significant investments of time and resources.

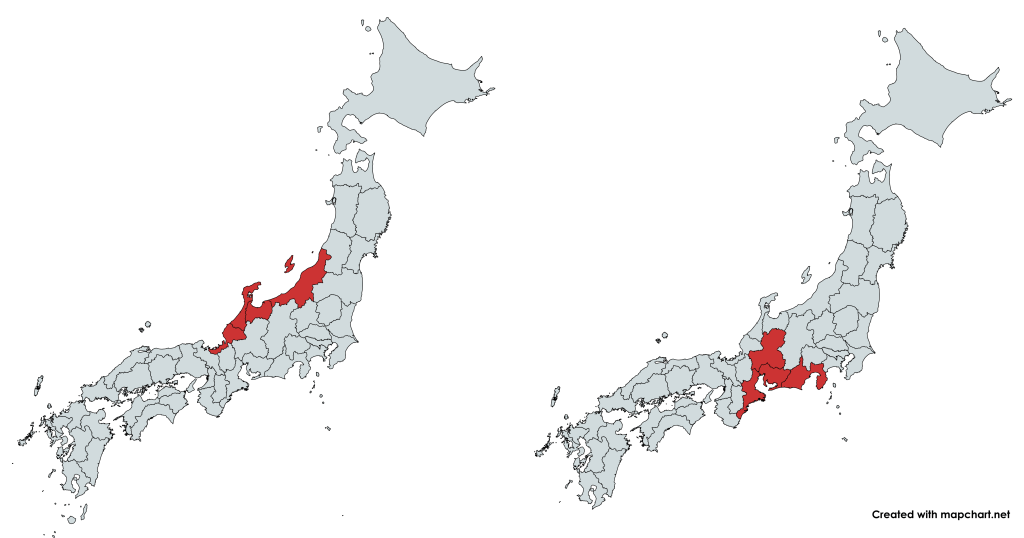

Kofun can be found across Japan (about 160,000 of them!) with the densest concentration being in modern day Hyogo Prefecture. While these tombs vary widely in their construction the basic idea remains the same, a tomb, grave goods (often looted, unfortunately) and a mound.

Burial mounds aren’t unique to Japan, but it is a general rule that the more elaborate the grave, the more resources the one who built it has. Now, this sounds obvious: rich people are rich, but being able to marshall sufficient manpower at a time when communication relied entirely on word of mouth demonstrates just how wealthy these kingdoms were becoming.

It is also important to note that they only started as tombs for important figures. By the later Yamato Period, there is evidence of (admittedly smaller) Kofun being built for relatively low status people, suggesting that wealth and resources had ceased to be the sole domain of monarchs.

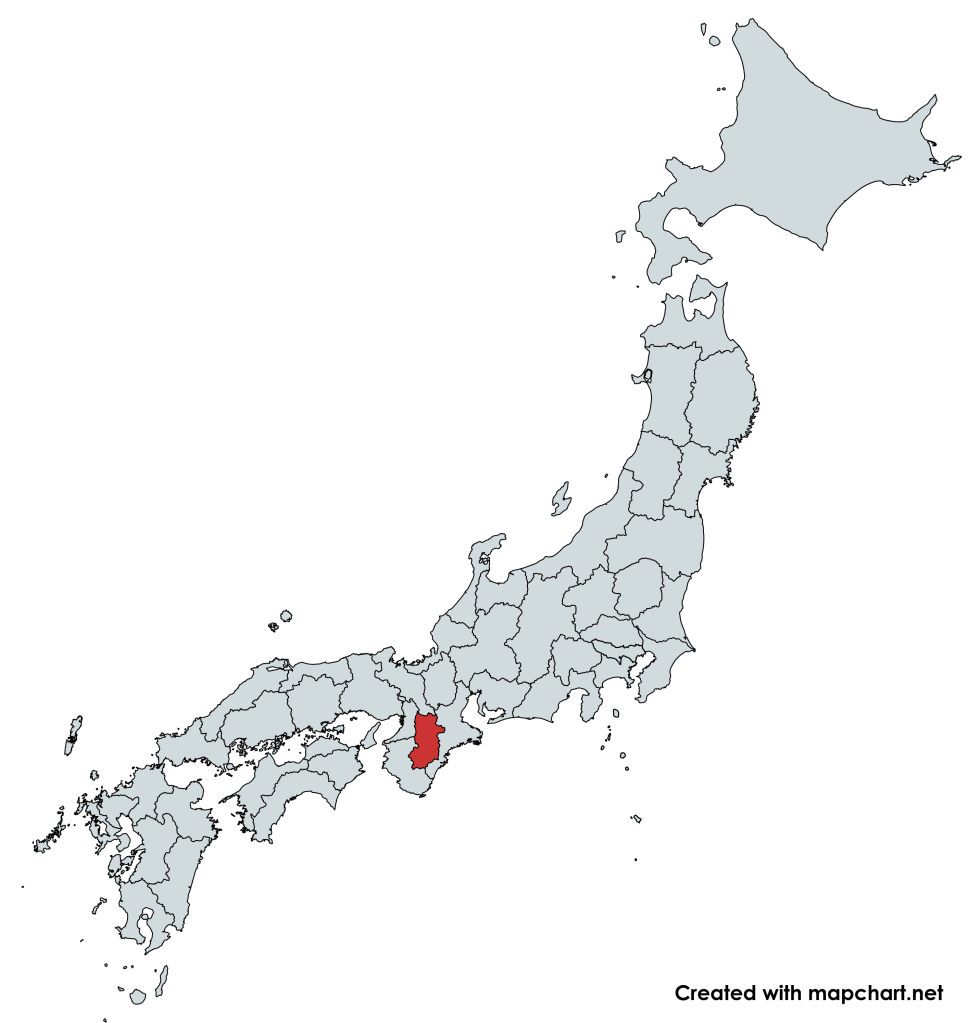

It was modern-day Nara Prefecture, however, where the most powerful and longest-lasting Kingdom got its start.

Difficult beginnings

The actual rise of the Yamato Kingdom is obscure (sorry, I know this keeps happening.) Since we rely almost entirely on Chinese sources to tell us what was going on in the earlier parts of this era, it is perhaps telling that they have relatively little to say about the origins of Yamato.

Although we don’t know for certain, it is suggested by some that this period was one of violence as rival kingdoms sought to assert dominance over their neighbours. Whilst we may never know for sure, by the early 5th Century, the Yamato Kingdom had risen to dominate most of central Japan.

Although the first power to dominate a significant part of Japan, the Yamato didn’t have it all their own way. On Kyushu, the Azumi and Hayato peoples were in control. The Azumi were apparently peerless seafarers and seem to have served as the first naval force of the Yamato. The Hayato, though also listed as loyal to the Yamato, were apparently a more tempestuous people, and there are records of several rebellions/wars between the Yamato and Hayato, with the Hayato eventually being subjugated and their population scattered throughout Japan.

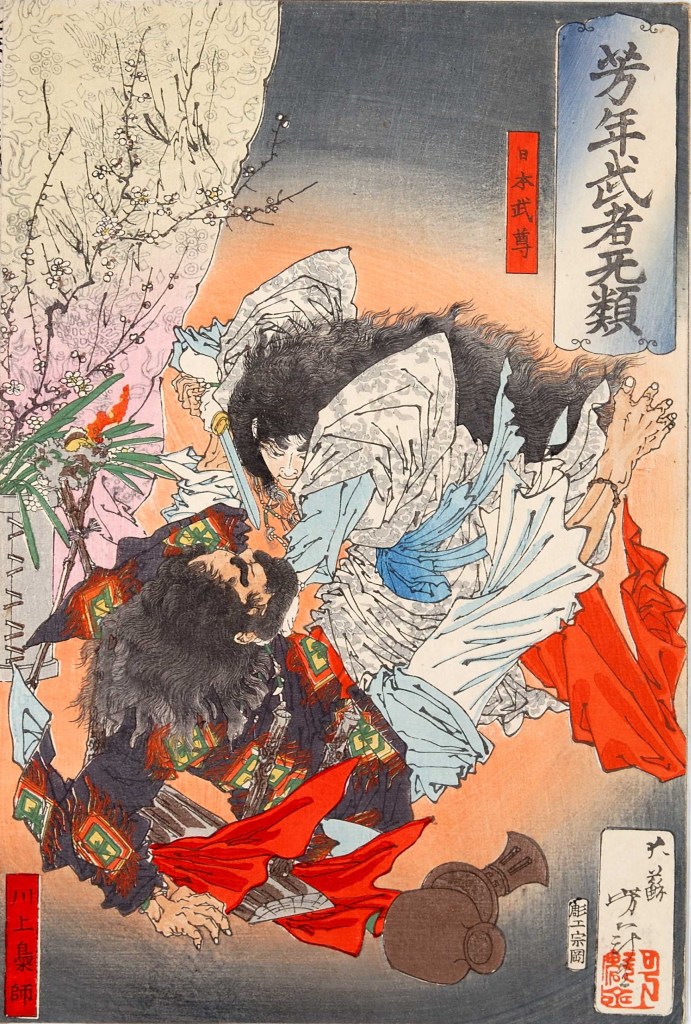

These people may have been related to or be the basis for the mythical Kumaso. Also, natives of Kyushu, the Kumaso, are supposed to have been implacable and dangerous foes of the Yamato, described as ‘bear-like’ (the word ‘Kuma’ means bear in Japanese) and monstrous. The story goes that the Kumaso were eventually defeated by the legendary Yamato Takeru, who killed their last leader by disguising himself as a woman at a feast, which is quite a way to go about it.

Chinese Influence

The Yamato State was heavily influenced by contemporary Chinese culture. This arrived in Japan through trade, cultural exchange, and waves of immigrants. For much of pre-modern history, China was viewed as the centre of the world, especially in Asia, and during these formative years, the Yamato people looked to China as the source of culture and learning.

Japan maintained direct maritime links with the Chinese Song Dynasty (possibly facilitated by the aforementioned Azumi), but also had close ties to the Kingdoms of Korea. Some sources even go so far as to suggest that hundreds of the noble families of this period actually originated in Korea. In fact, it is speculated (somewhat controversially) that, if the genealogy of the Imperial Family can be believed, they are of Korean origin as well.

How much we can believe ancient, often conflicting sources is a matter of debate, but we know for certain that Chinese and Korean culture was hugely influential in early Japan. Grave goods uncovered in Kofun show either direct Chinese and Korean origin or are heavily inspired by the same.

We also know that the early Yamato Kingdom based itself politically on China. It is known that early Yamato rulers petitioned the Chinese Emperors for royal titles, and the Chinese seem to have been happy to oblige.

In turn, the Yamato Kings bestowed titles of nobility on their subjects, including those in Kyushu, far from the centre of Yamato Power.

These clans varied in power, but drew legitimacy from the King. Each clan seems to have been ruled by a patriarch, who was responsible for keeping the Clan in line, but also took on a religious role, making sure the Gods (or Kami) of their Clan were kept happy. This is the role of the King in miniature and shows how formalised Yamato society had become. The King was at the top, responsible for the well being of the nation, and he would intercede with the Gods on the Kingdoms behalf.

Other Chinese innovations taken to by the Japanese were Buddhism (which I know is actually from India, but it arrived in Japan in its Chinese form) and, much to the lamentation of anyone who has ever tried to study Japanese, a written language, the origins of Kanji, Chinese written characters adapted to Japanese speech.

We’re actually going to continue this look at the deeper impact of Chinese culture next time, as the introduction of new religious and political ideas led to the Taika Reforms, which really deserves its own post.

Sources

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0028

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Himiko

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yamato_period

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Azumi_people

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yamato_Kingship

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hayato_people

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kumaso

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Five_kings_of_Wa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asuka_period