As you’ve probably guessed by now, the Sengoku Period was not marked by the sudden collapse of central authority, but rather a gradual decline that lasted decades, with many opportunities to stem the rise of chaos, and dozens of clans rising and falling with the tides of fate.

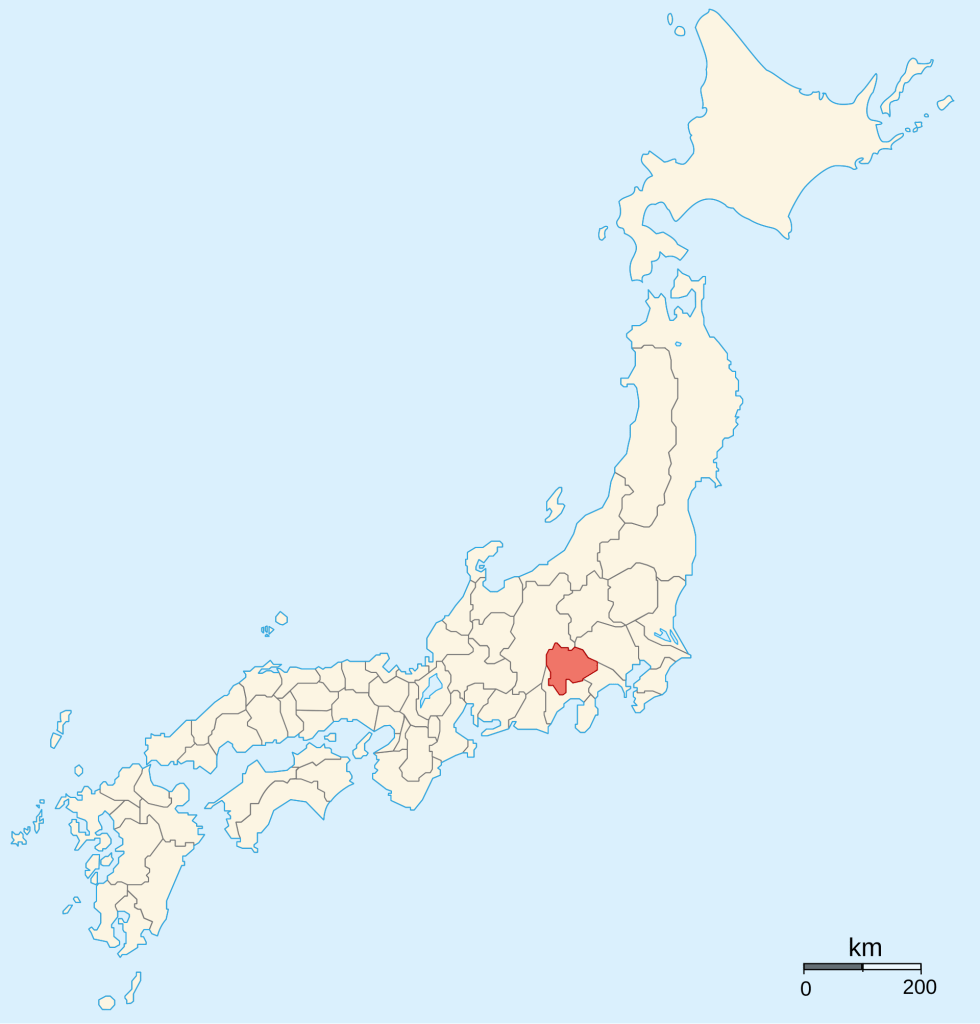

Mukai – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15552998による

The Takeda are a good example of this. They were, at least by the standards of the age, an old clan. One of their earliest ancestors had been a servant of the Minamoto Clan and had been appointed governor of Kai Province in 1029. Their fortunes would waver in the following centuries, and there would eventually be branches of the Takeda Clan in several key positions around the realm, though in order to keep things simple, we’ll be focusing on the branch of the family based in Kai Province, as they are arguably the most significant and certainly the most famous.

In 1180, the Takeda supported Minamoto no Yoritomo in his struggles against the Taira Clan in the Kanto, and they would be rewarded by having two of their sons appointed governors (shugo) of Totomi and Suruga Provinces. Yoritomo would apparently come to regret this decision, however, and revoked these governorships, and even drove some members of the Takeda Clan into exile or forced suicide, before apparently being reconciled with the clan, and recognising one of their members, Nobumitsu, as shugo of Kai.

Later, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear, the Takeda would be removed as shugo of Kai, being replaced by the Nikaido Clan. Quite why the Takeda ran afoul of the Shogunate, and what they were up to during this period, isn’t very well recorded, but the next time the clan shows up in the records, they’re back in charge of Kai, under their new head, Masayoshi.

In 1331, with the outbreak of what became called the Kenmu Restoration, Masayoshi remained loyal to the Kamakura Shogunate for a time, but when the writing was on the wall, he switched sides, supporting the Emperor and helping to put down outbreaks of rebellion from Shogunate loyalists in 1335.

This support for the Emperor would backfire, however, as the short-lived restoration was itself overthrown by Ashikaga Takauji, bringing about the Nanbokucho (Northern and Southern Court) Period. The Kai Takeda were evidently loyal to the Southern Court, and Takauji and his Northern Court had them overthrown and replaced with a distant relative from a different (Aki Province) branch of the clan, retaining the name Takeda, but hopefully proving more loyal to the new government.

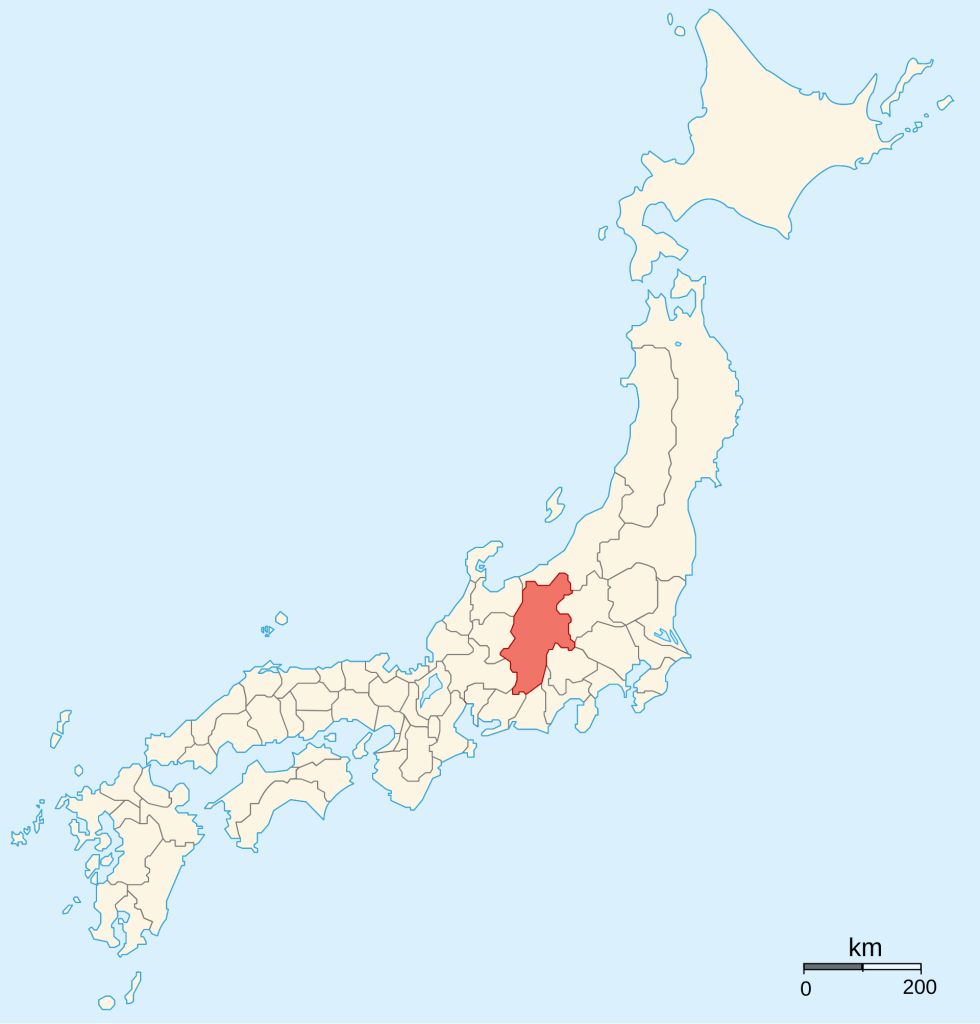

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1683068

This would prove to be a false hope, unfortunately. In 1416, the Uesugi Clan rose in rebellion against the authority of the Shogun in the Kanto in what became called the Zenshu Rebellion (named for the fellow who instigated it). The head of the Takeda, Nobumitsu, was Zenshu’s father-in-law and supported his rebellion. Zenshu was crushed, however, and not long after that, the Takeda suffered the same fate, coming under attack by a vengeful Shogunate, forcing Nobumitsu to commit suicide.

This left a power vacuum in Kai Province, which was partially filled by the Itsumi, supported by the new power in the Kanto, Ashikaga Mochiuji. If you think you’ve heard that name before you’re right; Mochiuji would also come into conflict with the government in Kyoto, and his defeat would bring his supporters down with him. Seeking stability in the area, the Shogunate would install Nobumitsu’s son, Nobushige, as governor of Kai.

Despite this, the Takeda’s position wasn’t strong. Though they had a prestigious name and lineage, the real power in Kai Province had fallen into the hands of clans who were their nominal deputies, primarily the Atobe and Anayama Clans, the latter of whom were distant relatives of the Takeda. Nobushige would actually be killed trying to subjugate the Anayama in 1450, and his son, Nobumori, would also die just 5 years later, leaving Nobumasa, a boy of just eight, to contend with the clan’s many enemies.

The Takeda, though nominally shugo of Kai Province, were practically powerless against the Atobe Clan, but that would change in 1464, when the head of the Atobe died and Nobumasa, by now a man, and supported by clans from neighbouring Shinano Province, decisively defeated the Atobe at the Battle of Yukarizawa, after which the Atobe leadership was obliged to commit suicide, and the remainder of the clan were exiled from Kai.

If you thought that’d be the end of Nobumasa’s troubles, however, then I really don’t know what to tell you; these blog posts are full of seemingly never-ending struggle, and poor Nobumasa wasn’t likely to be the exception. In the 1470s, his lands were attacked by neighbouring rivals, and though he was able to defeat them, his counterattack was itself stopped, and to make matters even worse, there are many contemporary reports of famine and epidemics spreading throughout Kai, giving us some idea of how dire the situation really was.

As late as 1490, other clans within Kai became restless, and this was compounded in 1492, when Nobumasa supposedly resigned as head of the clan to become a monk. This wasn’t in any way unusual, but he made the same mistake so many lords before him had made, and had more than one son, who swiftly got into a dispute over who would succeed.

Kai would descend into Civil War, interrupted briefly in 1498 when the rival factions united to face down an invasion from outside (led by one Hojo Soun), only to swiftly turn on each other again when the danger had passed. Nobumasa would die in 1505, with the clan still divided, and though he would later be remembered as a man who laid the foundations for the unification of Kai, he was also criticised for his actions that led to an internal conflict that severely weakened the Takeda.

This conflict would drag on until 1508, when Takeda Nobutora (Nobumasa’s grandson) defeated his Uncle and forced him to commit suicide, ending the fighting and finally uniting the Takeda under a single lord. Clan unity didn’t mean provincial control, however, and Nobutora would be obliged to spend considerable time subduing local clans who were still opposed to the idea of Takeda control of the whole province.

In 1515, Nobutora’s troubles only grew when the neighbouring Imagawa Clan invaded Kai, apparently on the pretext of avenging the assassination of the head of the Anayama Clan, who were divided over the question of whether to support the Takeda or the Imagawa. The Imagawa would have the better of the fighting initially, defeating Nobutora at occupying Katsuyama Castle in modern Kofu, laying waste to the surrounding countryside.

According to records, Nobutora was down, but not out, and a counterattack in 1517 defeated the Imagawa and tipped the scales back in favour of the Takeda. Though the fighting would drag on for nearly another year, both sides were facing issues elsewhere, and there was a strong impetus to make peace.

With the Imagawa withdrawing from Kai, Nobutora brought another clan, the Oi, to heel by marrying the daughter of their lord, the eponymous Lady Oi. Around this time, Nobutora built a new capital for the clan at Tsutsujigasaki Castle in modern Kofu, a centralising move that led to a brief outbreak of rebellion that Nobutora put down in 1520.

江戸村のとくぞう (Edomura no Tokuzo) – 投稿者自身による著作物, CC 表示-継承 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37253581による

Not long after that, the Imagawa again invaded Kai, nominally in support of the Fukushima Clan, who were still opposing Nobutora’s centralisation efforts. This war would see the Imagawa defeated, the Fukushima subdued, and Kai Province finally (though not yet firmly) united under the Takeda and Nobutora.

Throughout the 1520s and 30s, Nobutora would campaign within Kai’s borders and look to extend them. He would also seek prestige and legitimisation from the Imperial Court and the Shogunate, asking for formal rank and approval from the Shogunate for his control of Kai. Though both Imperial titles and Shogunate power were largely ceremonial by this point, the prestige of the titles was still sought after, and it shows that, despite his success, Nobutora was still not secure.

Outside of Kai, Nobutora would ally with the Uesugi Clan against the Hojo (still called the Ise at this point), invading territory in modern-day Kanagawa and Tokyo in support of the Uesugi, and to expand his own domains. In 1525, however, he would make peace with the new head of the Hojo clan, Ujitsuna, though that would be short-lived, as the Hojo asked for permission to march across Takeda lands in order to attack the Uesugi, permission that was refused by Nobutora, who did not view peace with the Hojo as meaning he had turned on the Uesugi.

Nobutora would defeat the Hojo in 1527, but a permanent peace would prove elusive, and the conflict would continue. In the same year, a letter arrived from Kyoto, asking Nobutora to march on the capital and intervene in the Hosokawa Rebellion. It was rumoured that Nobutora intended to march, but whether he changed his mind or was simply distracted, it never happened.

Instead, in 1528, he invaded neighbouring Shinano Province, and continued his support of the Uesugi against the Hojo in the area around modern Tokyo. Then, in 1531-32, he faced another rebellion from lords within Kai, who were apparently upset with his continued support for the Uesugi. This rebellion was put down, but it again serves to highlight just how busy Nobutora was during this period.

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1691770

In 1536, Nobutora, accompanied by his son, Harunobu (on his first campaign), conquered Saku Country in Shinano, marking the first territory outside of Kai that he had managed to secure. Following this, he secured alliances with the Suwa Clan of Shinano, and then, in 1539, a peace with the Hojo that secured his southern border, at least for a time.

Then, in 1541, he launched another campaign into Shinano, securing more territory there, and bolstering his allies, leading to the further boosting of Takeda’s power and prestige. Nobutora’s time as the leader of the Takeda and master of Kai Province would come to an abrupt end in June of that year, however, when his son, Harunobu, launched a sudden coup, forcing him into exile.

The exact reasons why Harunobu decided to overthrow his father will probably never be known for sure, but modern scholars suggest that the people of Kai had been left exhausted and practically destitute by Nobutora’s near-constant campaigning. Wars cost money, and the people of Kai were broke, so when Harunobu overthrew him, no one was sorry to see Nobutora go.

It has been suggested, however, that talk of dissatisfaction and poverty in Kai was a later fabrication meant to justify Harunobu’s coup after the fact. It has been pointed out that there are very few mentions of any mismanagement or hostility towards Nobutora from the common folk of Kai. Taking this into account, and the fact that Harunobu would engage in just as much, if not more, war than his father, we might be able to conclude that the coup was little more than a power grab, and a successful one at that.

Regardless of the reasons, Harunobu was now in charge, and the course of history was forever changed, because Harunobu would go on to become one of the most famous warlords of his era, a man who, if fate had been a little kinder, might have been the one to end the fighting and reunite the country.

Harunobu isn’t the name he’s best remembered by, though. This giant of Japanese medieval history is better known as Takeda Shingen.

*cue dramatic music*

Sources

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AD%A6%E7%94%B0%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AD%A6%E7%94%B0%E4%BF%A1%E9%87%8D

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AD%A6%E7%94%B0%E4%BF%A1%E5%AE%88#

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AD%A6%E7%94%B0%E4%BF%A1%E6%98%8C#

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AD%A6%E7%94%B0%E4%BF%A1%E8%99%8E#

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%BA%91%E8%BA%85%E3%83%B6%E5%B4%8E%E9%A4%A8

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8B%9D%E5%B1%B1%E5%9F%8E_(%E7%94%B2%E6%96%90%E5%9B%BD%E5%85%AB%E4%BB%A3%E9%83%A1)

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AD%A6%E7%94%B0%E4%BF%A1%E7%B8%84

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B7%A1%E9%83%A8%E6%B0%8F#

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AD%A6%E7%94%B0%E4%BF%A1%E5%85%89

Leave a comment