By the 1380s, the Northern and Southern Court Period (Nanbokucho Jidai in Japanese) had been dragging on for nearly 50 years. This was a period of frequent conflict, and the instability had only served to weaken the power of the central government in Kyoto.

In 1368, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu became the third Ashikaga Shogun. As he was still a minor at the time, the government was initially in the hands of his Kanrei (Deputy) Hosokawa Yoriyuki, whom we talked about last time.

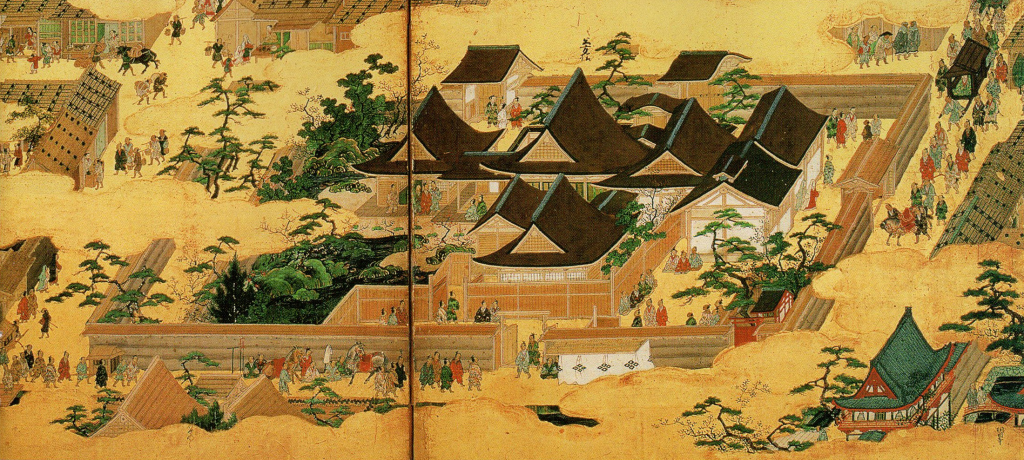

In 1378, Yoshimitsu assumed power in his own right. He also moved the official Shogunate residence to the Hana-no-Gosho, or Flower Palace, in the Muromachi area of Kyoto. Because of this, the Ashikaga Shogunate is sometimes called the Muromachi Shogunate, though we’ll keep calling them Ashikaga for now, to avoid any more confusion.

When Yoriyuki was forced to resign by his enemies during the Koryaku Coup, he was replaced by Shiba Yoshimasa, and the wider Shiba Clan saw their fortunes improve further still as Yoshimasa moved to fill several government positions with his family and retainers.

If you imagine that the Koryaku Coup was a matter of the Shiba Clan replacing the Hosokawa, then you’d be wrong. In fact, after 1379 (the year of the coup), the power of the Shogunate increased considerably, with the centralisation of government put in place by Yoriyuki falling not into the hands of the Shiba, but the Shogun himself.

Some historians have speculated that Yoshimitsu actually worked to engineer the conflict between the Hosokawa and Shiba Clans, playing both factions off each other in order to increase his own power. Whilst there are no clear records of any such plan, Yoshimitsu took advantage of the chaos to ensure that no one clan would be in a position to challenge him again.

Imperial Politics

During the 1380s, Yoshimitsu worked to tighten the bonds between the Shogunate and the Imperial Northern Court, whilst ensuring that one was clearly superior to the other.

The exact relationship between the Imperial and Shogunate government at this time is a bit complicated, but officially, the Shogun served as the Supreme Military commander nominally at the Emperor’s service.

In reality, of course, the Shogun was a military dictator, ruling the nation in all but name, but formally the Emperor ruled, while the Shogun merely served. To get around this legal technicality, Shoguns were often granted formal rank in the Imperial hierarchy and would often take up positions in the ‘Imperial’ government, further cementing their legitimacy.

We won’t go into the exact nature of the Imperial hierarchy, but in short, there were nine ranks, with the top three being divided further divided into Senior and Junior levels, whilst ranks four to nine (also called ‘initial rank’) were further divided into four levels (Upper Senior, Lower Senior, Upper Junior, and Lower Junior) for a total of thirty ranks.

By the 14th Century, Imperial Rank no longer granted very much in the way of actual political power, but it was a mark of prestige, and continues to be so today, although the ranks were reorganised during the 19th Century Meiji Restoration.

Yoshimitsu was not the first, or last, Shogun to take on Imperial Rank and title, but he did so at a time when the formalities of the Imperial Throne were more important than they would eventually become. By 1382, he had been granted Junior First Rank and took the position of Minister of the Left, effectively Prime Minister.

In his position as Minister of the Left, he began using the Imperial bureaucracy to issue orders and instructions, effectively turning Shogunate orders into Imperial ones, increasing their weight considerably, and obliging many troublesome lords to fall in line. It was one thing to oppose the Shogun, but another entirely to go against the Son of Heaven.

Controlling the Imperial Government relied on harnessing the reflected prestige of the Emperor’s Divine heritage, but being Shogun was, and remained, a primarily military position. Whilst Imperial decrees brought a lot of minor lords into line, there were still several powerful clans in Japan who would not bow to anything other than force.

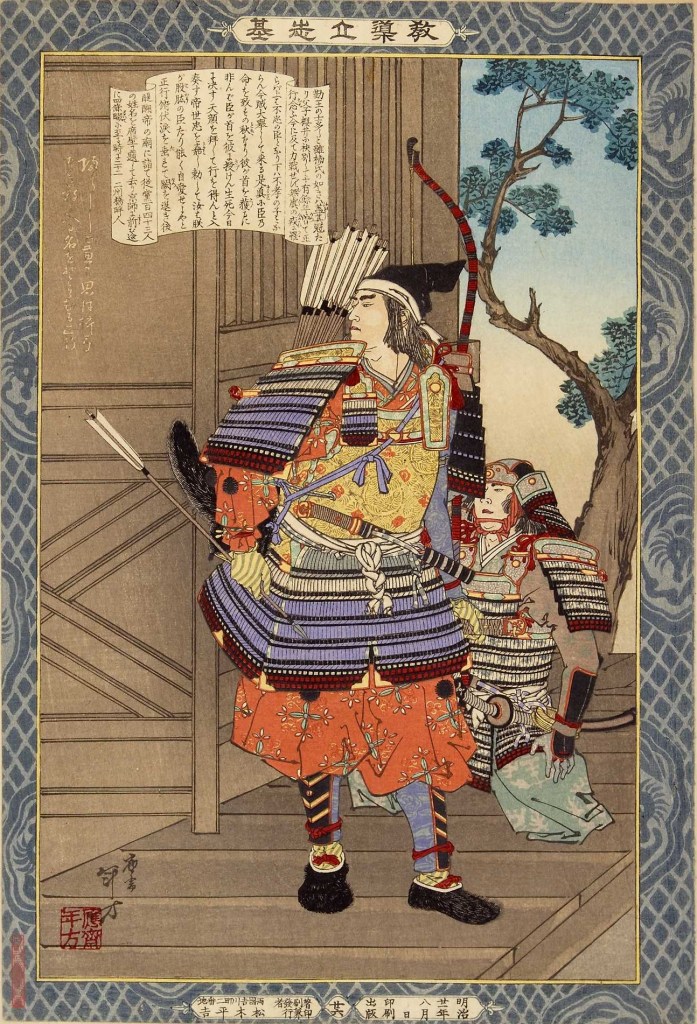

Yoshimitsu the Warrior

Fortunately for the Shogunate, Yoshimitsu proved himself adept at playing this role too. You may remember that the Koryaku Coup in 1379 had been led by three clans, the Shiba, Toki, and Yamana; however, it is the Toki and Yamana Clans who are important for this next bit.

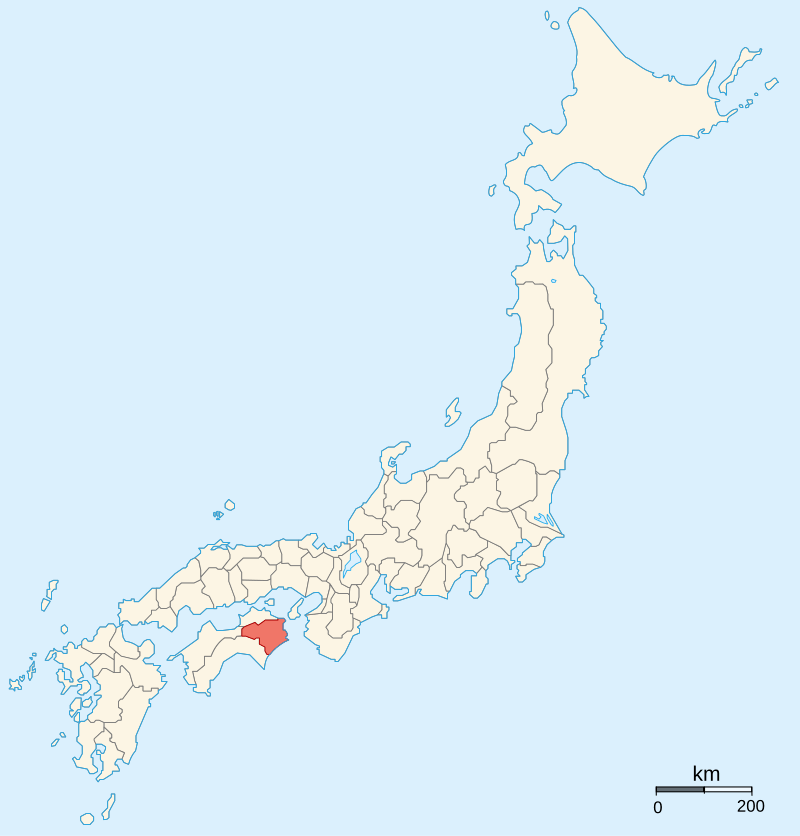

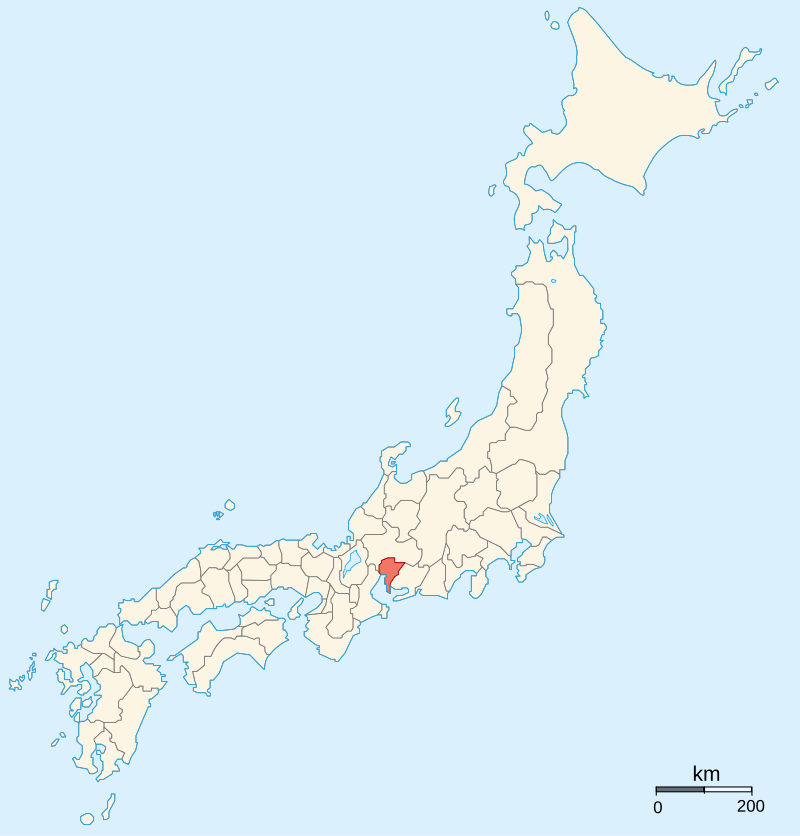

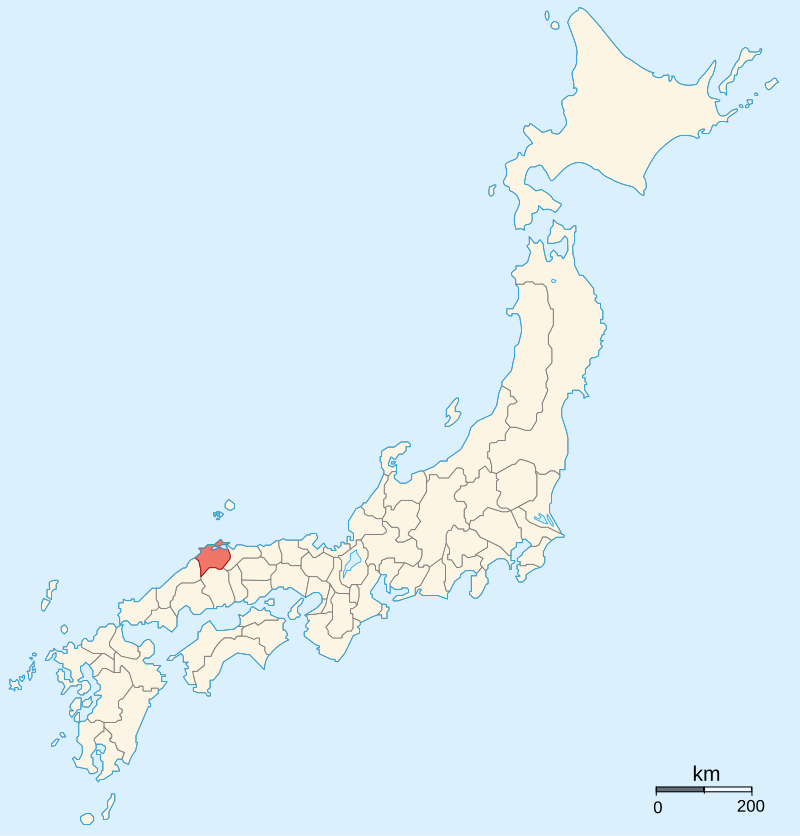

By the late 1380s, the Toki Clan ruled three provinces, whilst the Yamana (through various family members) controlled eleven. These power blocs were far too strong for the Shogun to take on directly; however, in 1388, the head of the Toki Clan died. Instead of allowing the heir, Yasuyuki, to inherit all three provinces (Mino, Ise, and Owari), the Shogun declared he’d only get two (Mino and Ise), whilst the third (Owari) would go to his brother, Mitsutada.

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1691740

It should come as little surprise that Yasuyuki and Mitsutada, despite being brothers, didn’t get along, and it wasn’t long before Mitsutada, who by all accounts was an ambitious sort, began plotting against his brother. Although the details are a bit murky, forces loyal to Yasuyuki attacked Mitsutada and forced him to flee to safety in Kyoto.

This act of near fratricide was exactly what the Shogun wanted. Mitsutada had been appointed as Shugo (military governor) of Owari Province, and Yasuyuki had committed an act of rebellion in throwing him out.

Shogun Yoshimitsu declared Yasuyuki a traitor and ordered loyal forces (led by other members of the Toki Clan, which just highlights how complex family relations were amongst Samurai) to bring him to justice. Yasuyuki was defeated by this coalition, and in the aftermath, the Toki Clan were deprived of Ise Province, whilst the family was split into two branches, one ruling Owari, the other Mino.

Yasuyuki would survive this episode and would actually return to favour under the Shogunate less than a year later during the Meitoku Rebellion (which we’ll talk about in a minute). Yasuyuki would regain control of Ise Province in 1391, whilst his treacherous brother, Mitsutada, would be deprived of Owari in the same year, apparently due to cowardice and mismanagement.

This whole episode shows that Shogun Yoshimitsu understood the nature of power politics in this period. Rather than destroy the Toki Clan outright, he weakened just enough to remove them as a threat to the Shogunate, but not so much that they could no longer govern what remained of their territories effectively.

After dealing with the Toki, Yoshimitsu turned his attention to the Yamana. As we discussed earlier, at this point, the Yamana Clan controlled eleven provinces in Eastern Japan. However, it should be noted that, much like the Toki, the Yamana Clan were not a single, united family. Instead, there were four brothers who were apparently united in name only.

Good Policy, or Good Fortune?

Yoshimitsu took advantage of this and pitted the brothers against each other. Some historians claim this was a deliberate policy of the Shogun, whilst others counter that strife within the Yamana family was nothing new, and Yoshimitsu simply grasped an opportunity.

Throughout 1391, Yoshimitsu had strengthened his position, defeating the Yamana Clan and dismissing his Shiba Kanrei, replacing him with Hosokawa Yoritomo, son of Hosokawa Yoriyuki, who had been overthrown during the Koryaku Coup back in 1379.

This is often cited as evidence that Yoshimitsu was moving against all three clans. He had engineered the downfall of the Toki, removed Shiba members of his government, and gone out of his way to take advantage of the Yamana’s division, whilst attempting to provoke them into doing something rash.

In November 1391, one of the Yamana brothers, Mitsuyuki, seized Yokota Manor in Kyoto. The exact circumstances aren’t clear. It is certain that Mitsuyuki took control of the Manor, but it’s not clear if his doing so was actually illegal. The Manor had been an Imperial property, but had come into the hands of the Yamana Family some years earlier; therefore, it’s possible that Mitsuyuki believed he was simply claiming a property that belonged to his family.

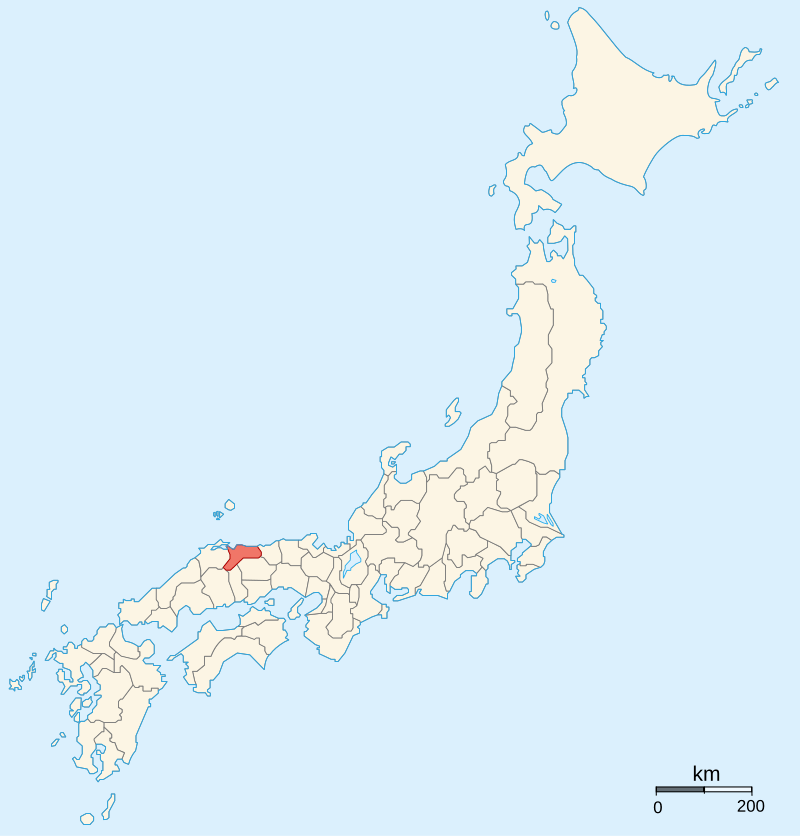

The Shogun and Northern Imperial Court didn’t agree, however. They argued that the property was owned by the head of the Yamana Clan, not Mitsuyuki himself. It is possible that Mitsuyuki was genuinely mistaken, but he had violated the peace, and so the Shogunate confiscated his province (Izumo) as a result.

By Ash_Crow – Own work, based on Image:Provinces of Japan.svg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1682749

Now, if you’ve been paying any kind of attention so far (and I hope you have) then you’re probably aware that Samurai aren’t the type to take this sort of thing on the chin, and Mitsuyuki began agitating amongst his relatives, claiming that the Shogun was planning to do to the Yamana what he had done to the Toki, which, to be fair, was probably true.

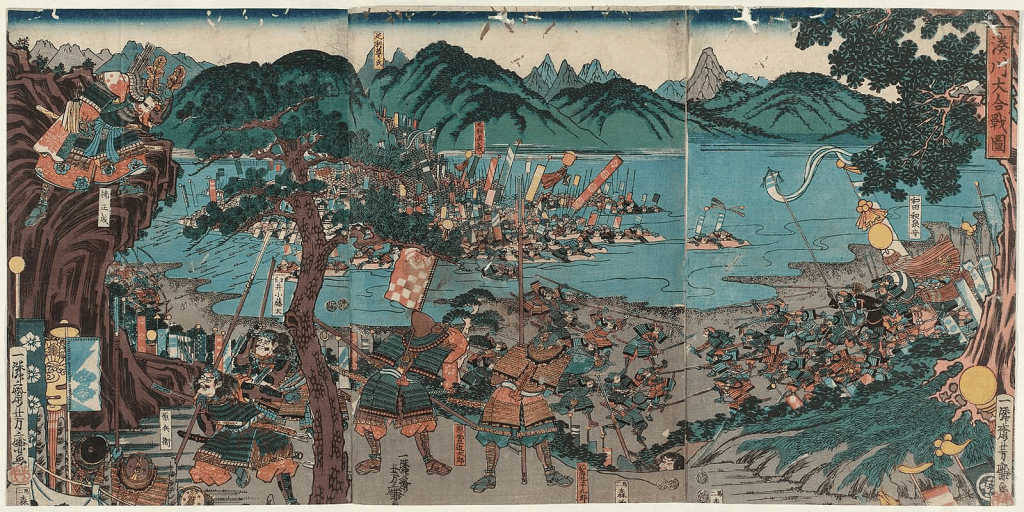

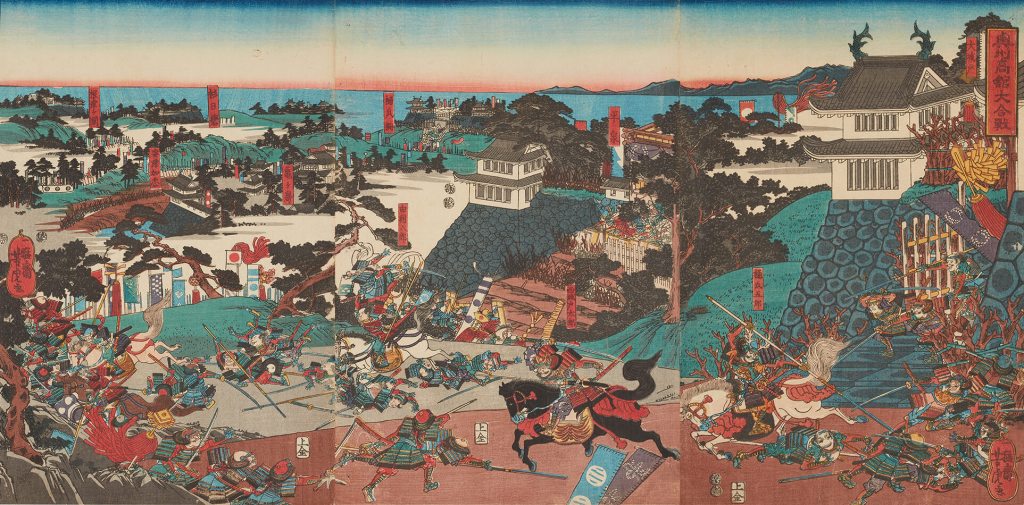

Having successfully raised an army, Mitsuyuki and the Yamana marched on Kyoto, where they were met by Shogunate forces led by Yoshimitsu himself. Outnumbered 2-1, the Yamana were defeated, their leaders were killed, captured, or put to flight, and the so-called ‘Meitoku Rebellion’ was brought to a swift conclusion.

Mitsuyuki himself would escape, and there would be further uprisings of Yamana loyalists until his capture and execution in 1395, but for all intents and purposes, the Yamana were broken. In the direct aftermath of their rebellion, they were reduced from eleven provinces to just three, and although the Yamana Clan would survive, they could no longer challenge the Shogun.

There would be a similar rebellion in 1399, when the next powerful clan, the Ouchi, would have to be dealt with, but their conflict with the Shogun ended much the same as the other two, with defeat, a reduction in land, but the overall survival of the clan.

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu could arguably be considered the best of the Ashikaga Shoguns, but his most enduring legacy is not found on the battlefield, but in dynastic politics, which we’ll talk about next time.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashikaga_shogunate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashikaga_Yoshimitsu

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%B3%E5%88%A9%E7%BE%A9%E6%BA%80

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%98%8E%E5%BE%B3%E3%81%AE%E4%B9%B1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%9C%9F%E5%B2%90%E6%B0%8F

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%9C%9F%E5%B2%90%E5%BA%B7%E8%A1%8C%E3%81%AE%E4%B9%B1

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%8A%B1%E3%81%AE%E5%BE%A1%E6%89%80

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanboku-ch%C5%8D_period